Life

| [commonly Wolfe Tone; gen. regarded as founder of Irish Republican tradition;] b. 20 June, 1763, 44 Stafford St. [now Wolfe Tone St.], Dublin, son of a coachmaker Peter Tone - who survived his son and latterly held a position in Dublin Corporation (d. 1805); related to the Woulfe family [see Kilwarden]; foundation scholar at TCD in 1784; took time from studies to tutor sons of Richard Martin (“Humanity Dick”), Co. Galway, and played at Robert Owenson’s theatre in Kirwan-Lane, Dublin (taking the roles of Lord Randolph in Douglas and Diggory in All the World’s a Stage); studied law at King’s Inns; eloped with Matilda [var. Mathilde] Witherington, whose gaze he first met from her an upper window of her father’s draper-shop in Grafton St., 1785 - she being 16 at the time; entered Middle Temple, 1787; called to the bar, 1789; |

| published Belmont Castle, or Suffering Sensibility (1790), with Richard Jebb and John Radcliffe, being a roman à clef and romantic spoof satirising Gothic fiction and contemporary Irish society; issued A Review of the Conduct of the Administration (1790); issued An Argument on Behalf of the Catholics of Ireland (Sept. 1791), a pamphlet by “A Northern Whig”, attacking the legislative-independence constitution secured from the British govt. by Grattan’s party and urging republican separatism; sold 10,000 copies by repute; travelled to Belfast with Thomas Russell, and met the Ulster radical William Drennan, et al., 10 Oct. 1971; founded with others the United Irishmen in weeks following and became leader of UI in Dublin; taken on as paid secretary of Catholic Committee, July 1792; appt. secretary to Catholic Association, 1792, and organiser of Catholic Convention - called Back Lane Parliament, at the Tailor’s Hall in Francis St. - appt. by Thomas Keogh and replacing Richard Burke, an appointment made with the support of Theobald McKenna (who had written the Declaration of the Catholic Society of Dublin to promote unanimity between Irishmen and remove religious prejudices (1791); |

| organised the Catholic Convention in the Tailors’ Hall, Dublin, Dec. 1792; reacted to Harpers’ Festival with often-cited diary-entry, ‘The harpers again. Strum. Strum and be hanged’ (13 July, 1792); authored “Ierne United” about the same time; disturbed by anti-Popery displayed by Protestant United Irishmen celebrating Bastille Day in Belfast; disappointed by the Catholic Relief Act, 1793 which led to the dissolution of the Catholic Committee by agreement with the Crown; Tone was then voted a sum of £1,500 with a gold medal; when William Jackson, a Republican clergyman, was arrested as a spy for the French in April 1795, Tone’s memorandum on Ireland in his possession led to his being investigated; permitted to depart for America as a condition of non-arrest [i.e., exile], having signed a confession of treason; attained agreement that he would not give evidence against Jackson; |

| remained in Dublin until after Jackson’s trial; before departure, he met with other Ulster United Irishmen at Cave Hill, Belfast, and undertook to continue with plans for revolution, May 1795; arrived Paris via Philadelphia with letters of introduction to the French Committee of Public Safety, under nom de guerre, “Citizen Smith”; wrote “Memorandums, Relative to my Life and Opinions”, in Paris, 7 & 8 Sept. 1796, later forming the basis for the Life ed. by widow and son, many of Tone’s papers for 1793-95 period being lost; worked on “Invasion Manifesto” (‘Address to the People of Ireland’, March-Sept. 1796; General Hoche appointed to Irish expedition with Tone as adjutant-general by Directorate; |

| sailed 15 Dec. 1796 with 43 ships and 15,000 men; scattered by storms; rejoined Hoche in Holland; death of Hoche, Sept. 1797; following news of the 1798 Rebellion, Tone sailed with Gen. Hardy and 2,300 men aboard flagship of Commodore Jean-Baptiste Bompard’s fleet incorporating the man-of-war Hoche, sixteen frigates and a schooner, 12 Oct.; recognised by British officer formerly a college-mate at TCD and captured aboard Hoche in Lough Swilly, during an action against Rear Admiral John Borlase Warren involving 200 French casualties, having turned down the opportunity to escape aboard the fast-sailing Biche, 16 Oct. 1798; wrote in his diary, ‘A fig for disembowelling, if the hang me first’; a brother, Matthew, joined Humbert’s army, and was captured at Ballinamuck, and hanged at Arbour Hill, 29 Sept. 1798; |

| tried by Court Martial, 10 Nov. 1798, and answered the treason charges with a plea of guilty (“I mean not to give this court any useless trouble and wish to spare them the idle task of examining witnesses. I admit all the facts alleged”); sentenced to death by hanging, under protest from General Hardy at his ignominious treatment as a criminal; gave his pocket book to John Sweetman - now in the National Museum; asked to be shot and refused by Lord Cornwallis; embraced a Senecan death by cutting his own throat [severed his trachea] with a penknife on 11 Nov., the morning appointed for his execution, being discovered weltering in his own blood (“I find then I am but a bad anatomist” - words spoken to the surgeon Lentaigne); execution deferred on plea of his father while Curran was preparing an irrefutable challenge to the use of martial law against him; d. 19 Nov. 1798, eight days after from inflammation of lungs; his body surrendered to a relative, William Dunbavin, of 65 High St.; immediate interment ordered by Govt.; |

| bur. Bodenstown, Co. Kildare, designated by Patrick Pearse ‘the holiest spot in Ireland’, and the site of annual republican pilgrimage on second last Sunday in June (with sep. commemorations by Fianna Fáil and Sinn Féin/IRA); Matilda remained in Paris on hearing news of his death; supported by French grant, and a collection among friends in Ireland; lost a dg. Maria, aged 16, and afterwards a son; her surviving son William Theobald Wolfe Tone was educated at the Imperial Lyceum on the authority of Napoleon, and afterwards received a commission, serving as aide-de-camp to Génèral Bagneris; wrote an account of Napoleon’s last campaign; Matilda m. Mr. Wilson, a constant companion, in 1816; his son William emig. to America, and was joined by his mother and step-father in late 1817; William m. dg. of William Sampson [q.v.]; Matilda was again widowed, and d. in Georgetown, 1849 [aetat. 81]; |

| Tone’s his Journals, recording ‘a faithful transcript of all that passes in my mind, of my hopes and fears, my doubts and expectations in this important business’, were published there as The Autobiography of Wolfe Tone by William, assisted by Matilda, Washington 1826; a new edition was issued by Maunsel & Co. in 1912; the originals are held in TCD; numerous anonymous political pamphlets of which no scholarly edition; there is an oval portrait by an unknown hand in the NGI; a modern Wolfe Tone Society was founded by Dr Roy Johnston, 1963; the 1826 life was reissued in its complete form, with passaged excluded by Tone’s family reinstated (ed. Thomas Bartlett 1998); there is a full-length portrait-statue by Edward Delaney on the Shelbourne corner of St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin, and another at The Square, in Bantry, Co. Cork. CAB ODNB PI JMC DIB DIW DIL RAF FDA OCIL |

|

|

|

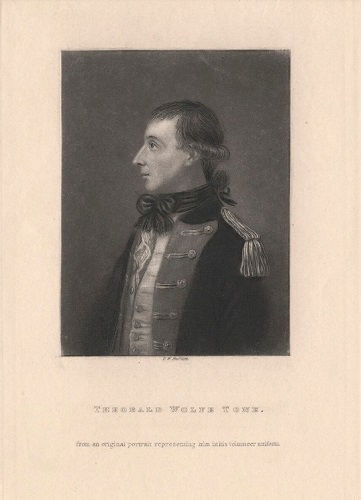

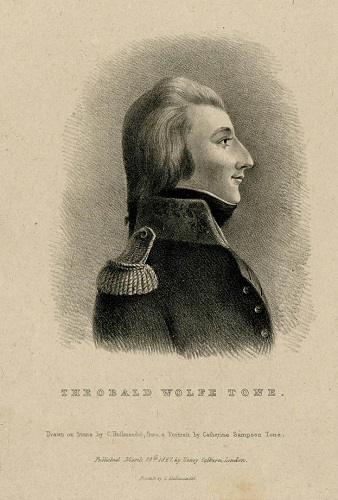

| Left: Tone by unknown artist; Middle: Tone as an Irish Volunteer, mezzotint by J. Huffam from the unknown portrait [NPG, London] - the same appearing in R. R. Madden’s United Irishmen (1846); Right: Tone Drawn on Stone by C. Hullmandel from a [miniature] Portrait by Catherine Sampson Tone [dg.-in-law]; published March 26th, 1827 by Henry Colburn, London. Note: there is an engraving of the “Capture of Wolfe Tone” on shipboard which bears no physical relation to the subject [see pixels.com - et al.]. | ||

[ top ]

Works| Fiction |

|

| [ top ] |

| Political writings |

|

| Reprints of The Life of Theobald Wolfe Tone [var. titles] |

|

| In Translation, Beatha Theobald Wolfe Tone, mar do fríth ‘na scríbhinní féin agus i scríbhinní a mhic [William T. Wolfe Tone]; Agus ar n-a thionntódh go Gaedhilg do Phádraig Ó Siochfhradha (Baile Átha Cliath: Oifig Díolta Foillseacháin Rialtais 1932), xvi, 716pp., 8o. [port.] |

| Selections |

|

|

[ top ]

Bibliographical details

An Argument on Behalf of the Catholics of Ireland [...] (Dublin: Patrick Byrne 1791), [2], 54pp., and Do. (Dublin: reprinted by order of the United Irishmen 1792), 16pp.; and Do. [another edn.] by “A Northern Whig” (Belfast 1796), iv, 28pp., and Do. [another edn.] (Dublin: Connolly Books 1969), [1], 40pp., and Do., with new intro. [British & Irish Communist Organisation] (Belfast: Athol Books 1973), [2],33pp., and Do. [rep.], ed. Brendan Clifford (Belfast: Athol Books 1992), 36pp. [See extracts.]

The Life of Theobald Wolfe Tone, founder of the United Irish Society and Adjutant General and Chef de Brigade in the service of the French and Batavian Republics / written by himself, and continued by his son; with his political writings, and fragments of his diary, whilst agent to the general and sub-committee of the Catholics of Ireland, and secretary to the delegation who presented their petition to His Majesty George III; his mission to France; with a complete dairy of his negotiations to procure the aid of the French and Batavian Republics, for the liberation of Ireland; of the expendition of Bantry Bay, the Texel, and of that wherein he fell; narrative of his trial, defence before the court-martial, and death; edited by his son, William Theobald Wolfe Tone, with a brief account of his own education and campaigns under the Emperor Napoleon written by himself and continued by his son; with his Political Writing, and [ ...] Diary, [ ...] Narrative of his Trial; Defence before the Court martial and Death, ed. by his son William Theobald Wolfe Tone, 2 vols. (Washington: Gales & Seaton 1826), I, vii, 566pp.; II: 674pp. Note: Tone wrote ‘Memorandums, relative to my Life and Opinions’, in Paris, 7 & 8 Sept. 1796, later forming the basis for the Life ed. by widow and son, with 17 surviving notebooks of his daily journal as supportive appendix. [See extracts.]

[ top ]

Criticism

|

| [ top ] |

| See also ... |

|

| Bibliography |

|

| Miscellaneous |

|

| Journals |

|

[ top ]

| Historical voices | |

| Edmund Burke Thomas Davis |

Patrick Pearse Rosamund Jacob |

| Modern commentators | |

|

Maureen Wall Francis Shaw, SJ Marianne Elliott Conor Cruise O’Brien Mary H. Thuente |

Rory Brennan Ian McBride Moira Tierney Bertie Ahern |

| See also de Valera’s Bodenstown address, 21 June 1925 quoted by Bertie Ahern - in Notes, infra |

| Seamus Heaney, “Wolfe Tone” - | |

| [...] Light as a skiff, manoeuvrable yet outmanoeuvred, I affected epaulettes and a cockade, wrote a style well-bred and impervious to the solidarity I angled for ... I was the shouldered oar that ended up far from the brine and whiff of venture, like a scratching post or a crossroads flagpole, out of my element among small farmers. |

|

| —from The Haw Lantern (1987). | |

Edmund Burke (Letter to Thomas Keogh, 17 Nov. 1796) [speaking of Tone]: ‘I conceive that the last disturbances, and those the most important, and which have the deepest root, do [414] not originate, nor have they their greatest strength, among the Catholics; but there is, and ever has been, a strong republican Protestant faction in Ireland, which has persecuted the Catholics as long as persecution would answer their purpose; and now the same faction would dupe them to become accomplices in effectuating the same purposes; and thus, either by tyranny or seduction, would accomplish their ruin. It was with grief I saw last year, with the Catholic delegates, a gentleman who was not of their religion, or united to them in any avowable bond of a public interest, acting as their secretary, in their most confidential concerns. I afterwards found that this gentleman’s name was implicated in a correspondence with certain Protestant conspirators and traitors, who were acting in direct connection with the enemies of all government and religion. He might be innocent; and I am very sure that those who employed and trusted him were perfectly ignorant of his treasonable correspondences and designs, if such he had; but as he has thought proper to quit the king’s dominions about the time of the investigation of that conspiracy, unpleasant inferences may have been drawn from it. I never saw him but once, which was in your company, and at that time knew nothing of his connections, character, or dispositions.’ (see further under Burke, Quotations, [letter to Thomas Hussey] supra; For full-text, see under Burke in RICORSO Library, “Irish Classics”, infra.)

Thomas Davis, “Tone’s Grave”: ‘My heart overflowed, and I clasped his old hand, / And I blessed him, and blessed every one of his band; / “Sweet, sweet ’tis to find that such faith can remain / To the cause and the man so long vanquished and slain.” / In Bodenstown churchyard there is a green grave, / And freely around it let winter winds rave -/ Far better they suit him - the ruin and the gloom - / Till Ireland, a nation, can build him a tomb.’ (The ’98 Song Book, n.d., p.12; cited in Loreto Todd, The Language of Irish Literature, 1989; also [in part] in Daithí Ó hÓgáin, The Hero in Irish Folk History, Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1985, p.317.)

Patrick Pearse: Pearse described Bodenstown, where Tone is buried, as ‘the holiest place in Ireland’ - ‘holier to us even than the place where Patrick sleeps in Down. Patrick brought us life but this man died for us [...] the greatest of all that have died for Ireland.’ (Marianne Elliott, Wolfe Tone, 1989, p.416; quoted in Paul Arthur, ‘“Reading Violence”: Ireland’, in David E. Apter, ed., The Legitimacy of Violence, Macmillan/UNRISD 1997, pp.234-91.)

Patrick Pearse: ‘Tone had appealed to that numerous and respectable class, the “men of no property”, and in that gallant and characteristic phrase he had revealed his perception of a great historic truth, namely, that in Ireland “the gentry” (as they affect to call themselves) have uniformly been corrupted by England, and the merchants and middle class capitalists have, when not corrupted, been uniformly intimidated, whereas the common people have, for the most part, remained unbought and unterrified.’ (The Sovereign People, March 1916; quoted in Peter Berresford Ellis, A History of the Irish Working Class, 1972, London: Pluto 1996 edn., p.224.) Note: comments from Ellis and Clarkson stress the identity of views with Connolly at this point.

Patrick Pearse: In The Separatist Idea (1916 [pamph.]), Pearse spoke of how ‘this heretic toiled to make free men of Catholic helots, how as he worked among them, he grew to know and love the real, the historic Irish people.’ (Centenary celebrations, 1898); further, ‘God spoke to Ireland through Tone’ (Separatist Idea, 1916 p.293).

The Freeman’s Journal on the death of Tone (edition of 20th Nov.): “Tone, that unfortunate and irreligious man, equally a rebel against the laws of his Country and his God, died yesterday morning in consequence of the wound which he inflicted on himself. An inflammation, which was the result, extended to his lungs and proved mortal. The Coroners Inquest sat on the body, and brought in a verdict of self murder—horrible crime. It is said, his head will be placed on the top of the New Prison, as his death does not exonerate him from such part of the sentence as can be put in execution—that is, if it shall be decided that he died in the legal possession of the military power.” (Quoted in Charles James Hume Hogan [President of Ulster Medical Society], “Who fears to speak of ’98?” [presidential address, 26 Oct. 1989] - available online; accessed 21.01.2022.)

[ top ]

Rosamund Jacob, The Rise of the United Irishmen 1791-94 (George Harrap 1927) relies heavily on his Autobiography, and defends him against he imputation of only caring to advance Catholics as a strategy for mobilising support for the fully democratic principles of the French Revolution. [See Jacob, q.v.]. Jacob cites at length passages from An Argument on Behalf of the Catholics of Ireland’, by “A Northern Whig” (pseud. of Tone), and writes that for the first time in Anglo-Irish politics the voice of honest truth was speaking, in sentences which again and again flash out to illuminate webs of complicated situations and events with a sudden searchlight of comprehension’ [55]. She quotes, inter alia: ‘The misfortune of Ireland is that we have no National Government, in which we differ from England and from all Europe’. Further: ‘If we withhold the sacred cup of liberty from our Catholic brother, and repel him from the communion of our natural rights, let us at least be consistent and cease to murmur at the oppression of the Government which grinds us.’ Also: ‘It [the revolution of 1782] was a revolution which left three-quarters of our countrymen slaves as it found them, and the Government of Ireland in the same base and wicked and contemptible hands who had spent their lives degrading and plundering her.’ Also: ‘We prate and babble and write books and publish them, filled with sentiments of freedom, and abhorrence of tyranny, and lofty praises of the Rights of Man! Yet we are content to hold three million of our fellow creatures and fellow subjects in degradation and infamy and contempt, or, to sum up all in one word, of slavery!’ (Autobiography, Vol. I., pp.344-362; here pp.55-56.) See also The Rebel’s Wife (Kerryman 1957), a Jacob’s novel about Mathilda Witherington Tone.

Francis Shaw, SJ, ‘The Canon of Irish History - A Challenge’, in Studies: An Irish Qaurterly Review, Summer 1972, pp.113-53 - see extensive remarks on Wolfe Tone and his influence on Patrick Pearse - including the following: ‘Tone’s political philosophy was relatively simple. It had in it two main elements: the first was an unqualified enthusiasm for the ideals of the French revolution; the second [...] was a deep hatred of England, with a desire and purpose of revenge. Towards the end of his life Tone had persuaded himself that he had always hated England, but his own writing reveal unmistakealy that this was not so. In fact, Tone’s hatred of England had in its origins nothing to do with Ireland. It was a personal affair. Tone was snubbed by a British prime-minister and he swore to be avenged. In the last nomth of his life he still brooded over this grieveanfe which he dated from his student years in London. the snub was Pitt’s complete lack of interest in Tone’s project to set up a British colony in the Sandwich islands from which “the colonists should devastate the territories of Spanish America and plunder the churches.” The project, Tone told Pitt, was conceived in “the daring and invincible spirit of our old buccaneers” and it was to be “a terror to Spain and the pride of England.” At this time Tone in London decided not to return to Ireland but “to quit Europe for ever” and to seek his fortune as a soldier with the India Company - incidentally abandoning his wife and child: this was prevented only by an accident of time. / Tone’s knowledge of Ireland was very limited [...].’ (p.127; see page image in a separate window.)

Maureen Wall, Catholic Ireland in the 18th c., ed. Gerard O’Brien (1989), quotes Vindication of the Catholics of Ireland (Dublin 1793), quotes remarks arising from charges of riot and tumult levelled at the general committee: ‘They [Catholics] know too well how fatal to their hopes of emancipation anything like disturbance must be; independent of the danger to those hopes, it is more peculiarly their interest to preserve the peace and good order than that of any body of men in the community - they have a large stake in the country, much of it vested in that kind of property which is most peculiarly exposed to danger from popular tumult, the general committee would suffer more by one week’s disturbances, than all the members of the two houses of parliament.’ (p.20; a copy of this pamphlet is printed in Life of Tone, I, pp.411-35, under a variant title.)

[ top ]

Marianne Elliott, Wolfe Tone : Prophet of Independence (1989), ‘[Wolfe Tone’s Life was] the first nationalist reading of Irish history, a reading that was to become the gospel of Irish repblicanism. The elements of that gospel, stripped of its American and Grench terminology, are that the Catholics are the Irish nation proper; Protestant power is based on “massacre and plunder” and the penalisation of the Catholics, reducing them to slavishness which the Catholic Committee finally broke in 1792.’ (p.310; quoted in Paul Arthur, ‘“Reading” Violence: Ireland, in David E. Apter, ed., The Legitimacy of Violence, Macmillan/UNRISD 1997, pp.234-91.)

Marianne Elliott, Wolfe Tone (1989): ‘Tone’s output of articles on the Catholic issue increased dramatically in these weeks [Sept. 1792]. They are well-written and punchy in style, even if their content - the French Revolution’s destruction of popery, the injustice of taxation without representation - is unexceptional. Tone warns the Ascendancy that protection and allegiance are reciprocal. But in the long term it was a contest for power, as the Ascendancy realised, and Tone was disingenuous in depicting the Catholic campaign as nothing more than a demand for basic justice.’ (p.186.)

Further (Marianne Eliott, Wolfe Tone, 1989): ‘Tone was a faithful recorder of the events through which he lived. But his knowledge of Irish history was poor. In this he was typical of his time. Eighteenth-century Ireland did not produce a Hume or a Robertson, and what passed for Irish history was little more than propaganda, or, more charitably, committed history dictated by sectarian leanings. In the liberal ethos of Trinity College in the 1780s it was fashionable to take the Catholic side in debates on the 1641 rising. Tone was present at such debates, and if his friend Thomas Addis Emmet traced his own radicalism to the reading of Curry’s Civil Wars with its Catholic viewpoint, he cannot have been alone in that. Tone may have been writing some kind of political testimony for posterity, in Paris in 1796, but it is not always clear that this was his intention. He was simply writing history as it was written at the time. Yet in doing so he produced the first nationalist reading of Irish history, a reading that was to become the gospel of Irish republicanism. The elements of that gospel, stripped of its American and French terminology, are that the Catholics are the Irish nation proper; Protestant power is based on “massacre and plunder” and the penalisation of the Catholics, reducing them to slavishness which the Catholic Committee finally broke in 1792.

In this reading Protestant nationalism does not figure: The Catholic “patriot parliament” of 1689 (misdated in Tone’s account as 1688) he sees as fighting for “national supremacy”, because it denied the right of England to legislate for Ireland. But the narrow Protestantism of future Parliaments negates the validity of their similar stand. Nor does he recognise that the men of the “patriot parliament” were Old English, rather than Gaelic Irish, or that they never sought to assert their independence from England. The northern Presbyterians are spared such blanket condemnation by virtue of their anti-Englishness, anti-Episcopalianism and what Tone sees as their natural republicanism. In all he rather glamorises the Presbyterians and never comes to terms with their anti-poperly.’ (Elliott, 1989, p.310; of Tone’s ‘Memorandums, Relative to Mmy Life and Opinions’; quoted [in part] in Paul Arthur, ‘“Reading” Violence: Ireland’, in David E. Apter, ed., The Legitimacy of Violence, Macmillan/UNRISD 1997, pp.234-91.)Marianne Elliott (Wolfe Tone, 1989): ‘Critics of Tone get short shrift from Irish Catholics. Even in the 1930s, when physical-force methods were out of fashion, Frank MacDermot’s balanced life of Tone was attacked as showing “a complete lack of any philosophy of Irish history”, of a permanent underground nation ... the spirit of Ireland” working through such instruments as Tone. In the 1980s such views are denounce as “snobbish”, “toney” Hibernian, “shoneen” and “revisionist”- this last, a term normally applied to scholars using scientific standards research to re-interpret the myths and long-held truths of the past now used more frequently as a term of abuse to describe those who attack romantic nationalist historiography. [Quotes Danny Morrison, as given under Morrison, q.v., infra.] Tone was passionately Irish. But he was part of an élite and had a very Protestant perception of the Irish masses. He thought them vulgar, lacking in spirit and prone to graft and deceit. He had little sympathy with the romantic cultural nationalism which was beginning to develop in his own day, and would have decried the additional barrier erected between Irishmen by the new Irish state’s emphasis on Gaelic culture and language. / Nor was he the democrat of tradition, a reputation largely based on his much misunderstood reference to “the men of no property”. Its use by those seeking to find an element in Tone to which all religions can subscribe is on the increase. Tone had considerable compassion for the poor. But his opinion of their judgement and political capacities was low and he had no intention whatsoever of involving them directly in politics. Property in the eighteenth century meant first and foremost landed property. His “respectable” men of no property were the middle classes who composed the Catholic United Irish leadership alike. Irish republican separatism start as a campaign to secure political power for the middle classes. / But let’s not be pious. The Ulster Protestants who claim hatred of England and his takeover by Catholic republicans sons for their rejection of him, or the IRA, who point to his [419] support of “armed revolt” in justification of their claim to be “the followers of Tone” are both correct in their different ways. Tone did seek Irish independence, he did dislike England, he did resort to arms to achieve his aims. And whatever the impact of Presbyterianism on his thinking, he did link the cause of Irish nationalism to Catholicism. Constitutional nationalists sanitise the Tone tradition, taking safe elements, whitewashing the rest / Tone’s thought processes were simplistic, and one of his greatest failings was his inability to see the many gradations of opinion between the ultra-loyalist and the separatists. He also suffered from the common human tendency to conflate sacrifice with rectitude. Yet both trait were part of that single-mindedness which made him such an effective revolutionary. [...]’ (pp.418-19.)

Marianne Elliott, review of T. W. Moody, et al., The Writings of Theobald Wolfe Tone [Vols. 1 & 2], in Times Literary Supplement (17 Jan. 2003): ‘[...] Tone’s exposure to bigotry and prejudice in Ireland remains unequalled. Members of the Protestant Ascendancy were easy targets in the 1790s [... b] the Presbyterians and the Catholics (to whose cause he devoted his most active years before his exile from Ireland) did not escape what was often a savage pen. His criticisms of England are well known. Less noticed are his comments on the Catholic Church. [...] He praised those who were thinking constructively, but he also noted a distinct reluctance by the Catholic hierarchy to admit their own laity into decision-making positions in Catholic institutions, as well as a tendency of Catholic lay leaders to fall into line when the clergy said so. Tone is brilliant in these areas, exposing pettiness and unquestioned authority wherever he found them.’ Further: ‘He was particularly critical of the lower-class Irish in America: “They are as boorish and ignorant as the Germans, as uncivil and uncouth as the Quakers, and as they have ten time more animal spirits than both they are much more actively troublesome.”’ Elliott notes that ‘Tone’s usually critical comments about the sexual liberty which he observed in London, but more so in Paris, and the sway held by society hostesses like Joséphine de Beauharnais and Madame Tallien [...] are fully restored here, as are the restaurant receipts detailed for Thomas Russell and clearly considered by Tone’s widow as unsuitable for the image she was developing of a nationalist icon.’

[ top ]

Conor Cruise O’Brien, The Great Melody (1992), quotes Tone on the failure of the Irish Volunteer movement: ‘The Government seeing the Convention by their own act separate themselves from the great mass of the people who could alone give them effective force, held them at defiance; and that formidable assembly, which, under better principles, might have held the fate of Ireland in their hands, was broken up with disgrace and ignominy, a memorable warning that those who know not to render their just rights to others, will be found incapable of firmly adhering to their own.’ [250.] The world being divided between Burke and Paine, Tone thought that in England “Burke had the triumph of completely to decide the public; fascinated by the eloquent publication, which flattered so many of their prejudices, and animated by their unconquerable hatred of France [...] the whole English nation, it may be said, retreated from their first decision in favour of the glorious and successful efforts of the French people [...] But matters were very different in Ireland, an oppressed, insulted, and plundered nation. In a little time the French Revolutoin became the test of every man’s political creed.” (Autobiog., Lon. 1893, vol. 1, p.38) [470.] Tone left Ireland for America June 1795 after it had been discovered that he had been in contact with the Rev William Jackson, a French agent. [570] Burke tells Keogh in correspondence how ‘with grief he sa[w] last year with the Catholic Delegates a Gentleman [Tone] who was not of their Religion or united to them by any avowable Bond of public Interest.’ Further: ‘I afterwards found this Gentleman’s Name was implicated in a Correspondence with certain Protestant Conspirators and Traitors who were acting in direct connexion with the Enemies of all Government and all Religion.’ (Burke-Keogh, Corr. IX, 112-16.) [571.]

Mary Helen Thuente, ‘The Literary Significance of the United Irishmen’, in Irish Literature and Culture, ed. Michael Kenneally (Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1992), pp.35-62, noting that that Tone authored “Ierne United” at about the time when he entered in his diary, ‘Strum and he hanged’ (13 July 1792), citing the reference in Paddy’s Resource to the effect that ‘the following song [was] composed by Councillor Tone [and] sung by Mr M’Nally, of Newry, at the Celebration Banquet in this town, on Saturday last’ (i.e., third anniversary of the fall of the Bastille, the day after the disparaging entry; quotes song in full; sung to tune of Ballinamoney, but said by Mary Ann McCracken to have been sung to “Cruiskeen La[w]n” by Maria Tone. (pp.43-44.)

Rory Brennan, review of Belmont Castle, or Suffering Sensibility (rep. edn. 1998): notes that a copy of the book was signed by Tone for the seareant of the militia when he was held in Derry; regards it as a roman à clef in which Sir John Fillamar is Lord Charlemont and the eponymous Belmont his home; Tone himself is Hon Charles Fitzroy Scudamore, Richard Martin (Humanity Dick), Lord Claireville, and his wife Lady Elizabeth.

Ian McBride, review of The Life of Theobald Wolfe Tone, in Times Literary Supplement (23 Oct. 1998), notes that Aodh de Blacam’s life of Tone (1935) attempted to represent him as ‘one of the founders of modern Catholic Democracy’ and that he had never denied Christian doctrine; the Wolfe Tone Annual of th 1930 and 1940s endeavoured to prove that he could not have committed suicide and that he attended Mass in Paris.

Moira Tierney, writing on Matilda Tone, in The Irish Times (20 Dec. 1997), notes that Matilda began married life by protecting Tone him from a violent burglary and ran the family household on a shoe-string. Matilda wrote: ‘I see, feel and hear all that was round me 36 years ago, my little room and everything in it, my bed, my babe in arms and, above all, he that came every instant with a heart glowing with love and joy and tenderness to look if we were well, to caress and to bless us [...] how I was loved and cherished then!’ Further, ‘Tone has constantly disappointed me and though he has promised to come with me next Sunday certainly I shall wait no longer ... if all men knew how to treat women as Tom [Russell] does, we should be much better than we are’. Matilda crossed the Atlantic twice with their young family, and was living in the Paris of the Directorate when news of his death reached her in 1798; bombarded the Bonapartes Napoleon and Lucien, Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Perigord, and the Ministre de la Guerre for her rights as a general’s widow; lived in relative retirement dedicated to protecting Tone’s memory from revisionism; defended her one surviving son from tuberculosis and United Irish attempts to place him in the punishing Irish Brigade of the French army: ‘Do the Irish think that because Tone volunteered in their service and shed his best blood in their cause and left his family destitute in a foreign country that his posterity are to be their slaves?’ His son William sent to the prestigious Lycée Imperial; Matilda lived 20 years in France - ‘I am almost a Frenchwoman’; remarried, 1820; moved to Washington DC; edited the Life of Theobald Wolfe-Tone with her son. To Charles Hart who visited her in 1849: ‘I have been for the best part of my life, and I can tell you I am not very young, hoping and watching for something to turn up for that country [Ireland], but I am afraid that now there is no hope, it is too small ... do you know I sometimes wish it would grow’; outlived Wilson and all her children; died at 79; bur. Washington, her remains being transferred to Brooklyn at the sale of the cemetery in 1891; restored tombstone shows original inscription.

[ top ]

Andy Johnston, James Larragy, & Edward McWilliams [Irish Working Group], ‘James Connolly: A Marxist Analysis’, ser. in Permanent Revolution - Chapter 4: ‘The Irish Bourgeois Revolution, Part 2’: ‘[...] Tone, moreover, in 1796, when urging the French to send as large as possible an expedition, was concerned precisely that it would be big enough to inspire “men of a certain rank as to property [to] at once declare themselves” (Tone’s Life, ed. by William Tone, his son, Vol 2, p.197). In the same work his views as late as 1798, on the question of wholesale confiscation of the aristocracy’s land, are revealing. While he observed that the gentry, “miserable slaves”, “had furnished their enemies with every argument for a system of confiscation”, along the lines of the radical bourgeois land reform of the French Revolution, Tone argued that it would be “a terrible doctrine to commence with in Ireland” (Tone’s Life, Vol. 2, p.133). This weighs against even seeing him as the most politically advanced representative of the claims of the peasantry to the land. So, what is the meaning of his reference to the “men of no property”? / We believe it is essential to see the reference in its context. It arises in an account, in Tone’s own work (Tone’s Life, Vol. 2, p.46), of his negotiations with Delacroix, a representative of the French government, in March 1796. Delacroix doubted that it was possible to send an army on the scale required to attract the support of “those men of some property which was so essential in framing a government” (Tone had in mind a Convention including the liberal Catholic Committee on whose behalf he head written An Argument). Delacroix proposed a provisional military government if the invasion succeeded, just in case the Irish middle class did not rally to the French forces. The strong suggestion, in the whole context as explained by Tone himself, is that the rallying of the “men of no property” was put to Delacroix as a possibility that might further urge him on, rather than as something that was central in Tone’s own preferences.’ (Permanent Revolution, Issue of 30 Nov. 2006, online - accessed 28.03.2011; see index to the whole text under James Connolly, q.v. - supra.)

Bryan Fanning & Tom Garvin, The Books that Define Ireland (Sallins (Dublin): Merrion Press 2014) - Chap. 6: ‘William Theobald Tone (ed.,) the Autobiography of Wolfe Tone’: ‘[...] The first edition of the Autobiography edited out some passages of Tone’s journal. It incuded a memoir by Tone’s son and editor William, detailing his service as a cavalryman in the Napoleonic ears, and another memoir by Tone’s widow Martha [nee Fanning], recounting how after his death in 1798 she engineered an interview with Napoleon in order to secure French citizenship for her son. An 1883 edition of Tone’s Autobiography edited by Barry O’Brien was republished several times. This also excluded the passages censored by Wiliam. In 1888 a French edition was publisehd as Mémoires Secrets de Wolfe Tone; a portrait fo Tone still hangs in the foyer of the French ambassador’s residence in Dublin. A 1938 abridged edition by Sean O’Faoláin restored the censored passages. these includes Tone’s acocunt of his early amours, expressions of his contempt for his brother-in-law (“a most egregious coxcomb”), quarrels with his wife’s family (over prospective inheritances), and various scornful remarks about America. Tone lived there briefly in 1795 but couldn’t stand the place or its uncouth people. A definitive edition of the Autobiogrpahy was publisehd in 1998, edited Bartlett. This kept to the struture of the 1826 edition but included the excised passages, Tone’s correspondence and also reinstated political writings that had been excluded from various earlier abridged editions. Tone was an Irish patrtio for just the final eight years of his 35 year-long life. His political views were the product of his class, religion, and, in particular, his life experiences. Tone had a lust for life and craved personal advancement. He sought the latter first in the service of the British Empire and when rebuffed he made common cause with his fellow Irishmen against England.’ (q.p.)

Bertie Ahern, Speech at Wolfe Tone Commemoration, Bodenstown (Sun. 16 Oct. 2005): ‘Eighty years ago, in 1925, Eamon de Valera addressed a republican commemoration in this very place. De Valera opened his speech by saying: “Republicans, you have come here today to the tomb of Wolfe Tone on a pilgrimage of loyalty. By your presence you proclaim your undiminished attachment to the ideals of Tone, and your unaltered devotion to the cause for which he gave his life. It is your answer to those who would have it believed that the Republic of Ireland is dead and its cause abandoned.” [...; Ahern goes on:] Like de Valera, and all my other Fianna Fáil predecessors, I have tried to persuade the militant fringe of republicanism to follow our party’s peaceful and democratic Republican path. A key element of the story of the Irish peace process is how we, in Fianna Fáil, have advanced our constitutional republican analysis of partition and unity. Fianna Fáil holds that unity cannot be built on the divisions and fury of ages. We hold that it must be advanced through greater economic, social and cultural ties and understanding. We hold fast to Tone’s aim to rid this island of the evil of sectarianism and “to substitute the common name of Irishman in place of the denominations of Protestant, Catholic and Dissenter.” We oppose all efforts to impose unity through violence or the threat of violence.’ (Quoted on CAIN Web Service online; accessed 11.03.2011.)

[ top ]

| “Our independence must be had at all hazards. If the men of property will not support us they must fall. We can support ourselves by the aid of that numerous and respectable class of the community, the men of no property.” (Inscribed on flagstones at the grave of T. W. Tone [no punct.]) |

An Argument on Behalf of the Catholics of Ireland (1791): ‘The revolution of 1782 was a revolution which enabled Irishmen to set at a much higher price their honour, their integrity, and the interest of their country; it was a revolution, which, while at one stroke it doubled the value of every borough monger in the kingdom, left three-fourths of our countrymen slaves as it found them, and the government of Ireland in the base and wicked and contemptible hands who who had spent their lives in degrading and plundering her [...] The power remained in the hands of our enemies, again to be exerted for our ruin, with this difference, that formerly we had our distresses, our injuries, and our insults gratis, at the hands of England; but now we pay very dearly to receive the same with aggravation, through the hands of Irishmen; - yet this we boast of, and call a revolution.’ (Quoted in James Connolly, Labour in Irish History, 1934, pp.65-66; cited in Malcolm Brown, Politics of Irish Literature, 1972, p.20; also in Kevin Whelan, ‘The Other Within: Ireland, Britain and the Act of Union’, in Dáire Keogh & Whelan, eds., Acts of Union: The Causes, Contexts and Consequences of the Act of Union, Dublin: Four Courts Press 2001, p.14; rep. in T. W. Moody, R. B. McDowell & C. J. Woods, The Writings of Theobald Wolfe Tone, 1763-98, Vol. I, Oxford 1998, [as above, pp.112-13]; see longer extract in RICORSO Library, “Historical Studies” - via index, or direct.)

[ top ]

Life of Theobald Wolfe Tone (1826): ‘I made speedily what was for me a great discovery, though I might have found it in Swift or Molyneux, that the influence of England was the radical vice of our government, and consequently that Ireland would never be either free, prosperous or happy, until she was independent, that that independence was unobtainable whilst the connection with England existed.’ (The Life of Wolfe Tone, Washington: Gales & Seaton 1826, Vol. 1, p.32.)

Life of Theobald Wolfe Tone (1826): ‘This awakening of the spirit of liberty roused from their long slumber of slavery the oppressed and degraded Catholics; who, by a strange anomaly, forming the original population of the country and the mass of the people, were at that period, and are still in some respects, aliens in their native land. My father was the first Protestant who engaged in their cause to its whole length and experienced the greatest difficulty, in the beginning, to rouse them, if not to a sense of their wrongs, at least to the spirit of expressing them.’ (Memoirs of Wolfe Tone [1827]; quoted in John Philip Cohane, The Indestructible Irish, NY: Hawthorn Books 1969, p.53.)

| Permanent revolution?: ‘The wealthy and moderate party of their own persuasion, with the whole Protestant interest, would form a barrier against the invasion of property. ... Extend the electoral franchise to such Catholics only as have a freehold of ten pounds per year [and] abolish the wretched tribe of forty-shilling freeholders.’ (Quoted in Andy Johnston, James Larragy, & Edward McWilliams [Irish Working Group], ‘James Connolly: A Marxist Analysis’, ser. in Permanent Revolution - Chapter 4: ‘The Irish Bourgeois Revolution, Part 2’, citing T[om] Dunne, Theobald Wolfe Tone-Colonial Outsider, p.31.) - reflecting Tone’s ‘development over time from a Grattanite to a revolutionary democrat [which] illustrates the continuity in the rising struggle of the Irish bourgeoisie.’ (Permanent Revolution, Issue of 30 Nov. 2006, online - accessed 28.03.2011.) |

|

| Alfred Webb quotes Tone’s reflections on his wife Matilda: ‘Women in general, I am sorry to say, are mercenary, and especially if they have children, they are ready to make all sacrifices to their establishment. But my dearest love had bolder and juster views. On every occasion of my life I consulted her; we had no secrets, one from the other, and I invaryingly found her to think and act with energy and courage, combined with the greatest prudence and discretion. If ever I succeed in life, or attain at anything like station or eminence, I shall consider it as due to her counsels and example.’ |

| —Webb, Compendium of Irish Biography (1878), at LibraryIreland.com online [21.10.21]. |

Life of Theobald Wolfe Tone (1826): ‘To subvert the tyranny of our execrable Government, to break the connection with England, the never failing source of all our political evils, and to assert the independence of my country - these were my objects. To unite the whole people of Ireland, to abolish the memory of all past dissensions and to substitute the common name of Irishman in the place of the denominations of Protestant, Catholic, and Dissenter - these were my means.’ (Written in Paris, Aug. 1796; Life, 1826, p.69; quoted in Elliott, Theobald Wolfe Tone: Prophet of Independence, 1989, p.312.)

Life of Theobald Wolfe Tone (1826): ‘Our freedom must be held at all hazards; if the men of property will not help us they must fall; we will free ourselves by the aid of that large and respectable class of the community - the men of no property’ (Life of Tone, Washington Edn., 1826, II pp.46; quoted in Elliott, op. cit., 1989, p.418.)

[ top ]

Speech from the Dock (10 Nov. 1798): ‘The great object of my life has been the independence of my country; for that I have sacrified every thing that is most dear to man; placed in an honorable poverty I have more than once rejected offers considerable to a man in my circumstances, where the condition expected was in opposition to my principles; for them I have braved difficulty and danger: I have submitted to exile and bondage; I have exposed myself to the rage of the Ocean and the fire of the enemy; after an honorable combat that should have interested the feelings of a generous foe, I have been marched through the country in Irons to the disgrace alone of whoever gave the order; I have devoted even my wife and my children; after that last effort it is little to say that I am ready to lay down my life. / Whatever I had said, written, or thought on the subject of Ireland I now reiterate: looking upon the connexion with England to have been her bane I have endeavoured by every means in my power to create a people in Ireland by raising three Millions of my Countrymen to the ranks of Citizens. / Having considered the resources of this Country and satisfied that she was too weak to assert her liberty by her own proper means, sought assistance where I thought assistance was to be found; I have been in consequence in France where without patron or protector, without art or intrigue I have had the honour to be adopted as a Citizen and advanced to a superior rank in the armies of the Republic; I have in consequence faithfully discharged my duty as a soldier; I have had the confidence of the French Government, the approbation of my Generals and the esteem of my brave comrades; it is not the sentence of any Court however I may personally respect the members who compose it that can destroy the consolation I feel from these considerations.’ [Cont.]

Speech from the Dock (10 Nov. 1798) - cont. [immed.]: ‘Such are my principles such has been my conduct; if in consequence of the measures in which I have been engaged misfortunes have been brought upon this country, I heartily lament it, but let it be remembered that it is now nearly four years since I have quitted Ireland and consequently I have been personally concerned in none of them; if I am rightly informed very great atrocities have been committed on both sides, but that does not at all diminish my regret; for a fair and open war I was prepared; if that has degenerated into a system of assassination, massacre, and plunder I do again most sincerely lament it, and those few who know me personally will give me I am sure credit for the assertion. / I will not detain you longer; in this world success is every thing; I have attempted to follow the same line in which Washington succeeded and Kosciusko failed; I have attempted to establish the independence of my country; I have failed in the attempt; my life is in consequence forfeited and I submit; the Court will do their duty and I shall endeavour to do mine. [...]’ (Quoted in Marianne Elliott, Wolfe Tone: Prophet of Independence, 1989, pp.392-93 note: Elliott [op. cit., 1989] gives a full account the recording and publication of the speech and those parts excluded from publication by the court though ultimately published in 1849 in Lord Cornwallis’s Papers, including the sentence above: ‘For a far and open war [..., &c., as supra] (also quoted in Paul Arthur, ‘“Reading” Violence: Ireland’, David E. Apter, ed., The Legitimacy of Violence, Macmillan/UNRISD 1997, pp.234-91.)

Speech from the Dock (10 Nov. 1798): ‘For my earliest youth I have regarded the connection between Ireland and Great Britain as the curse of the Irish nation, and felt convinced that while it lasted this country could never be free or happy. My mind had been confirmed in this opinion by the experience of every succeeding year, and the conclusions which I have drawn from every fact before my eyes. In consequence, I determined to apply all the power which my individual efforts could move, in order to separate the two countries. [...] I have laboured to create a people in Ireland by raising three millions of my countrymen to the rank of citizens. I have laboured to abolish the infernal spirit of religious persecution by uniting Catholics and Dissenters. To the former I owe more than can ever be repaid. The service that I was so fortunate to render them they rewarded munificently; but they did more: when the public cry was raised against me, when the friends of my youth swarmed off and left me alone, the Catholics did not desert me.’ [He had enrolled in the French army] with a view to save and liberate my country’’ [he had failed, and] in a cause like this, success is everything. Success, in the eyes of the vulgar, fixes its merits. Washington succeeded, and Kosciusko failed.’ Further: ‘I would like to offer a few words relative to a single point - the mode of punishment. In France, our émigrés, who stand in nearly the same situation in which I suppose, I now stand before you, are condemned to be shot. I ask that the Court should adjudge me the death of a soldier and let me be shot by a platoon of grenadiers. I request this indulgence rather in consideration of the uniform I wear, the uniform of a Chef-de-Brigade of the French Army, than from any personal regard for myself.’ (Quoted in M. J. MacManus, Adventures of an Irish Bookman, Talbot 1952, p.57 [?var. Nov. 10]; also [in part] in Katie Trumpener, Bardic Nationalism: The Romantic Novel and the British Empire, Princeton UP 1997, p.303 [Introduction, n.76], quoting The Best of Tone, ed. Prionsias Mac Aonghusa & Liam Ó Réagáin, Cork: Mercier Press 1972, p.183.) [Note: full bibl. citation for Mac Aonghus & Ó Réagáin omitted in Trumpener.]

[ top ]

General Views

Happiest creature: ‘[At sixteen] I began to look on classical learning as nonsense; on a fellowship in Dublin College as a pitiful establishment; and, in short, I thought an ensign in a marching regiment was the happiest creature living.’ (Autobiographies, ed. R. B. O’Brien, London 1893, Vol. I, 9ff; quoted by MacDermot, Theobald Wolfe Tone, London 1939, p.7; cited in Stanford, Classical Tradition, 1986, p.216.)

Irish Provinces: ‘A country so great a stranger to itself as Ireland, where North and South and East and West meet to wonder at each other, is not yet prepared for the adoption of one political faith [...] Our provinces are ignorant of each other; our island is connected, we ourselves are insulated; and distinctions of rank and property and religious persuasion have hitherto been not merely lines of difference, but brazen walls of separation. We are separate nations, met and settled together, not mingled but convened - uncemented, like the image which Nebuchadnezzar saw, with a head of fine gold, legs of iron, feet of clay - parts that do not cleave to one another.’ (Quoted in Froude, The English in Ireland, 1895, Vol. 3, 12-13; cited in Joseph Leerssen, Mere Irish & Fíor Ghael, Amsterdam: John Benjamins Pub. Co. 1986, [q.p.]).

The Anglo-Irish Ascendancy: ‘What miserable slaves are the gentry of Ireland! [...] The very sound of independence seems to have terrified them out of all sense, spirit or honesty. If they had one drop of Irish blood in their veins, one grain of true courage or genuine patriotism in their hearts, they should have been the first to support this great object [... but] they see Ireland only in their rent rolls, their places, their patronage and their pensions’. (n. source; Rafroidi, op. cit., with bibl. A. Rivoallan, ‘Un Patriot[e] Irlandais, Theobald Wolfe Tone’, Annales de Bretagne, LXXIV, 1967, pp.279-97.)

See Tone on Edmund Burke, under Burke, Commentary, infra.

Irish Independence: ‘Our independence must be had at all hazards. If the men of property will not support us, they must fall: we can support by the aid of that respectable and numerous class of the community, the Men of no property.’ (Quoted in Paul Arthur, ‘“Reading” Violence: Ireland, in The Legitimacy of Violence, ed.Da vid E. Apter, Macmillan/UNRISD 1997, pp.234-91, p.246.)

Harpfest: Tone on the Belfast harp Festival organised by Bunting and wrote in his Journal: ‘All go to the Harpers ... poor enough; ten performers; seven execrable ... No new musical discovery; believe all the good Irish airs are already written ...’ (12 July 1792); ‘The Harpers again. Strum. Strum and be hanged’ (13 July, 1792; quoted in Breandáin Ó Buachalla, I mBéal Feirste Cois Cuain, 1968, p.25 [July 13th only]; also in R. L. McCartney, Liberty and Authority in Ireland [No. 9], Field Day Pamphlets 1985, p.13, and Katie Trumpener, Bardic Nationalism: The Romantic Novel and the British Empire, Princeton UP 1997, p.11.) Note: Ó Buachalla adds that Tone admits to a ‘sick-head’ [i.e., hang-over] on the occasion (being his second visit to Belfast), and adds this matter-of-fact comment on the Festival: ‘Poor enough: ten performers, seven execrable, three good; one of them, Fanning, far the best. No new musical discovery. Believe all the good Irish airs are already written.’

Happy days: ‘Feb. 29th 1796. I have now six days before me, and nothing to do: huzza! Dine every day at Beauvilliers for about half-a-crown, including a bottle of choice Burgundy which I finish regularly ... A bottle of Burgundy is too much, and I resolve every morning regularly to drink but the half; and every evening regularly I break my resolution [...]’ (Journal; quoted in Brian Inglis, Downstart, Chatto & Windus, 1990, p.171.)

John Ahearne [Capt.]: ‘N.B. I do not wish to hurt Aherne, but I had rather he was not employed in Ireland at first, for he is outré -and extravagant in his notions; he wants a total bouleversement of all property, and he has not the talents to see the absurdity and mischief, not to say the impossibility of this system, if system it may be called. I have a mind to stop his promotion, and believe I must do it. It would be a terrible doctrine to commence with in Ireland. I wish all possible justice be done to Aherne, but I do not wish to see him in a station where he might do infinite mischief.’ (R. Barry O’Brien, ed., The Autobiography of Wolfe Tone, 1763-1798, London 1893, Vol. II, p.53; quoted in Warwick Gould, “Lionel Johnson Comes First to Mind”: Sources for Owen Aherne’, in Yeats and the Occult, ed., George Mills Harper, London: Macmillan 1975, p.278.) Gould traces developments: ‘Captain John Aherne’s career with the secret Irish forces was doomed after Tone wrote of him in the terms we have seen. His reputation was sabotaged by the less than anarchical Tone and the French officials cancelled another trip which had been proposed for him to make to Ireland. Tone wrote of this, “I am not sorry on the whole that Aherne does not go to Ireland” [...] he went to Bantry with the ill-fated expedition [and] was again active in Hamburg in 1798 [...] captain of Napoleon’s Irish legion, and died suddenly on the march to Berlin after the Battle of Jena, in 1806. [&c.]’ (p.280; ref to Richard Hayes, Biographical Dictionary of Irishmen in France, 1949; Irish Swordsmen of France, 1934, et al.)

Bantry Bay (the failed landing): ‘Certainly we have been persecuted by a strange fatality from the very night of our departure to this hour.’ (Journal, Dec. 16th; quoted in Patrick Rafroidi, Romanticism in Ireland, Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1980, Vol. 1.)

[ top ]

References

Justin McCarthy, gen. ed., Irish Literature (Washingtpon 1904), gives extracts from Journal incl. ‘Interview with Napoleon’. See also William Theobald, infra.

| See Alfred Webb, “Theobald Wolfe Tone”, in Compendium of Irish Biography (1878) - at LibraryIreland.com online [21.10.21]. |

Frank O’Connor, ed., Book of Ireland (London: Collins 1979), gives extract from the Bantry Bay passages of Tone’s Journal, ‘... as to the embowelling, “je m’en fiche [I don’t care]”, if ever they hang me, they are welcome to embowel me if they please ... Nothing on earth could sustain me now but the consciousness that I am engaged in a just and right cause.’

Patrick Rafroidi, Irish Literature in English, The Romantic Period, 1789-1850, Vol 2 (1980), Bibl., cites modern edn. Autobiography abridged by Seán O’Faolain (London 1937); Frank MacDermot, Theobald Wolfe Tone and His Times (1939, rev. 1968); Anatole Rivoallan, Un Patriot irlandais [Annales de Bretagne, LXXIV] (1967).

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day Co. 1991), Vol. 1 selects An Argument on Behalf of the Catholics of Ireland [926-30]; See also Burke’s ‘Letter of Sir Hercules Langrishe’: I agree with you in your dislike of the discourses in Francis Street; but I like as little some of those in College Green ... better things might have been expected in the regular family mansion of public discretion, than in a new and hasty assembly of unexperienced men, congregated under circumstances of no small irritation [with ref. to the withdrawal of the liberal Viceroy Fitzwilliam’ [852n.]; the take-over of the committee by the United Irishmen, with Tone taking over from Richard Burke as agent [ibid, 853n.]; ‘democratic’ style [859]; through Tone, Northern dissent, French democracy, and Dublin middle-class lobbying come into combination [1076]; [further rems. at 1267]; Biog. & Bibl. [958-59].

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day Co. 1991), Vol. 2: Tone in popular song [77]; instead of Grattan, the nationalist hero becomes Tone for the Fenians, in Martin’s The Irish Felon and Mitchel’s United Irishman [172]; Pearse derived legitimacy from Tone and 1798 [213]; Michael Davitt, ‘Tone’s sacrifice [et al.; 277]; counted by Pearse among the ‘evangels of later days’ [292]; opined that the Dublin mob would be worthless (F. H. O’Donnell) [339]; ‘sunny spirit of toleration which was the glory of Grattan’s parliament and of Wolfe Tone’s United Irishmen’ (William O’Brien, 1918) [348]; ‘the first words of the United Irish charter, “this society is constituted for the purpose of forwarding the brotherhood of affection, a communion of right, and a union of power among Irishmen”; also adopted as first words of the United Irish League (William O’Brien, do.) [349]; [O’Casey’s Seamus, in The Shadow &c, ‘Many a true Irishman was a Protestant - Tone, Emmet an’ Parnell’ [ 694]; [cf. Peter, Act. II, Plough & Stars, 701; Yeats, ‘... All that delirium of the brave?’; 799]; Yeats, “16 Dead Men”, ‘[...] For those new comrades have they found, / Lord Edward and Wolfe Tone, / Or meddle with our give and take / That converse bone to bone?’ [807]; [?another rem. 854]; Rolleston, for Protestants [973]; James Connolly attacked the facility with which pillars of the nationalist community could participate in the 1798 centenary, in a scathing editorial, ‘Wolfe Tone and his “Admirers”’ (The Workers’ Republic, 5 Aug. 1899), 988; [Luke Gibbon, ed., 999], [Aodh de Blacam, 1016].

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day Co. 1991), Vol. 3, incls. references and remarks at pp.8, 38n, 382, 591, 549, 563, 570, 572, 476; [Francis Shaw, ‘The Canon of Irish History - A Challenge’, Studies, 1972, 591-95 passim]; Conor Cruise O’Brien, comments on physical force movement’s origin in his republican ideal [596-597]; idem, the IRA show from Tone that an Ireland politically connected with Britain is unfree [601]; Tone had come to despise everything which his own Episcopalian class stood for and regarded himself as an honorary Presbyterian in politics, if not in religion (Marianne Elliott, Watchmen in Zion, 1985) [607]; Joyce, ‘to deny the name of patriot to all those who are not of Irish stock would be to deny it almost all the heroes of the modern movement [e.g. Tone]’ (‘Ireland, Isle of Saints and Sages’, 1907) [667]; De Valera quotes Tone as expressing the republican ideal, and cites his words in the Sinn Féin constitution (Clare election speech, 1923 [744]; de Valera at Bodenstown, 21 June 1925 [746-47]; [also Yeats, 1323; Fiacc, 1331n].

[ top ]

Working Class Movement Library (Salford) holds, inter alia, early edns. of Tone’s Autobiography (1827 & 1828), another edn. by R. Barry O’Brien (1893), and one abridged by Sean O’Faolain (1937). Catalogue and webpage contains the note: ‘none of the editions so far published contains the full text of Tone’s journal, about one-tenth of the original having been excised for various reasons. The full manuscript is in Trinity College Library, Dublin. Oxford University Press is currently planning to publish it as part of a definitive edition of Wolfe Tone’s writings.’ (Presumably superseded by Bartlett’s edition.) [See online.]

Arthur Ponsonby, Scottish and Irish Diaries &c (1927), contains an extract from Life of Theobald Wolfe Tone (Washington 1826); another in Bernard Share, ed., Far Green Fields, 1500 Years of Irish Travel Writing (Belfast: Blackstaff 1992).

A. N. Jeffares & Peter Van de Kamp, eds., Irish Literature: The Eighteenth Century - An Annotated Anthology (Dublin/Oregon: Irish Academic Press 2006), pp.363-74, gives extracts from the Diary, Dec. 1796, recording the abortive expedition to Bantry Bay [2 Dec.-1 Jan.]

Hyland Catalogue (Oct. 1995) lists Leo McCabe [sic], Wolfe Tone and the United Irishmen: For or Against Christ?, Vol. 1 (1937) [ex. SJ Milltown Library].

[ top ]

Notes

United Irishmen’s Declaration: ‘First Resolved - “That the weight of English influence on the Government of this country is so great as to require a cordial union among all the people of Ireland, to maintain that balance which is essential to the preservation of our liberties and the extension of our commerce.” Second - “That the sole constitutional mode by which this influence can be opposed is by a complete and radical reform of the representation of the people in Parliament.” Third - “That no reform is practicable, efficacious, or just, which shall not include Irishmen of every religious persuasion. Satisfied, as we are, that the intestine divisions among Irishmen have too often given encouragement and impunity to profligate, audacious and corrupt administrations, in measure which, but for these divisions, they durst not have attempted, we submit our resolutions to the nation as the basis of our political faith. We have gone to what we conceive to be the root of the evil. We have stated what we conceive to be the remedy. With a Parliament thus reformed, everything is easy; without it, nothing can be done. And we do call on, and most earnestly exhort, our countrymen in general to follow our example, and to form similar societies in every quarter of the kingdom for the promotion of constitutional knowledge, the abolition of bigotry in religion and politics, and the equal distribution of the rights of men through all sects and denominations of Irishmen. The people, when thus collected, will feel their own weight, and secure that power which theory has already admitted to be their portion, and to which, if they be not aroused by their present provocation to vindicate it, they deserve to forfeit their pretensions for ever.” (See John Larkin, ed., The Trial of William Drennan, 1991).

Matilda Tone outlived two husbands and all her children; she was at first buried in Washington and moved to Greenwood Cemetery, Brooklyn, NY, 1891; her headstone was restored by the New York Irish History Roundtable and unveiled by Mary Robinson, 8 Oct. 1996, Nancy Curtin speaking on the occasion; the inscription reads: ‘Matilda, widow by her second marriage of Thomas Wilson. Born June 1769. Died March 18th, 1849. Revered and loved as the heroic wife of Theobald Wolfe Tone.’ [Marion R. Casey, et al., Irish List, Virginia, May 1998.]

Dock-speech: The sale of a 1798 proclamation and a previously unknown handwritten copy of Wolfe Tone’s speech from the dock before his death sentence was auctioned in Whyte’s having passed into the hands of descendants of General Sir George Hewitt, adj.-gen. of the British Army in Ireland in 1798. Tone [...] handed his own copy of the speech into the court and it remained in official British archives in Kew since then. A photocopy of this is held on microfilm in the National Library of Ireland. But emerged at the time of the auction that he had written out a copy in his prison cell and this was kept by General Hewett. Dr Sylvie Kleinman [reseracher in the TCD History Department] said that French archives showed Tone played a pivotal role in French military aid to the Irish rebellion and that the copies of the speech were mirror images of each other. (See Alan O’Keeffe, in Irish Independent, 19 July, 2020 - online; accessed 20.11.2021; paraphrased here.)

Kith & kin: It has been hinted that Arthur Wolfe, Viscount Kilwarden was the natural father of Wolfe Tone Along with his nephew Richard, Lord Kilwarden - who is often styled ‘a humane judge’ but whom John O’Donovan calls a ‘good-natured booby’ - was one of the few victims of the Robert Emmet’s Rebellion of 1803. (See John O’Donovan, ‘The Irish Judiciary in the 18th and 19th Centuries’, in Éire-Ireland, 6, 4, Winter 1971, pp.17-22; espec. p.21). Note var.: Tone was the natural son of a cousin of Arthur Wolfe [Lord Kilwarden], of being a member of the Wolfe family of Forenaughts, Co. Kildare. (See Wikipedia entry on Charles Wolfe [online].

Cockade: The cockade worn by T. W. Tone at his trial is held in the Jackie Clarke Library, Ballina, Co. Mayo (see History Ireland, May 2006, p.7).

Frank MacDermot, author of Theobald Wolfe Tone and His Times (London: Macmillan 1929; 1968), was the youngest son of Rt. Hon Hugh MacDermot, QC., of Coolavin; ed. at Downside and Oxford; bar; served in World War I; joined a merchant banking firm in NY; entered Irish politics on retirement, elected TD for Roscommon, 1932; appt. to Seanad [Senate] by Eamon de Valera, 1937; retired, 1942; acted as rep. of Sunday Times in NY and later Paris. Still living in 1968. (See back page of his life of Tone, 1968 edn.)

[ top ]