Life

| 1868-1916 [Gl. Séamas Ó Conghaile]; b. 5 June, Cowgate (“Little Ireland”), Edinburgh, of Irish immigrant parents from Co. Monaghan, John Connolly and Mary [née] McGinn; left school at eleven; began employment at printing works, 1882; enlisted under false name of Reid in Second Battalion of the Royal Scots Regiment (British Army) to escape poverty at 14, serving for 7 years, partly at Cork, later in Dublin; deserted from Curragh before his regiment was sent to India; fled to Perth, Scotland, 1889 [aetat. 21], accompanied by Lillie Reynold, a Scottish girl, whom he married, 20 April, 1890 - with whom three daughters [incl. 2nd child Nora, b.1893; Roddy b. 1901]; failed in business as a cobbler; became a carter in Edinburgh; encountered John Leslie, Labour politician (1873-1955?); became a trade unionist taking over from his brother John as Secretary of the Scottish Socialist Federation [var. Socialist Democratic Federation], May, 1895; become involved in Keir Hardie’s Independent Labour Party, fnd. 1893; learned and promoted Esperanto; |

|

|

| travelled to Ireland with his family as paid organiser of the Dublin Socialist Club, May 1896, becomeing founding member of the Irish Socialist Republican Party [ISRP], May 1896, with the stated aim of securing ‘national and economic freedom of the Irish people’; published ‘Erin’s Hope’ (1897); arrested in course of 1798 commemoration, June 21, 1897, Maud Gonne paying the fine for his release; published The New Evangel (1901); also Father Finlay, S.J., and Socialism: An Exposition of Social Evolution (1901); became fnd. ed. of Workers’ Republic, 1898-99; toured Scotland and England on behalf of the Socialist Labour Party in 1903 - a splinter from the SDF formed by Connolly with Neil Maclean and others impressed by Daniel De Leon’s Socialist Labor Party in America; joined protests by Maud Gonne and Arthur Griffith against Boer War; | ||

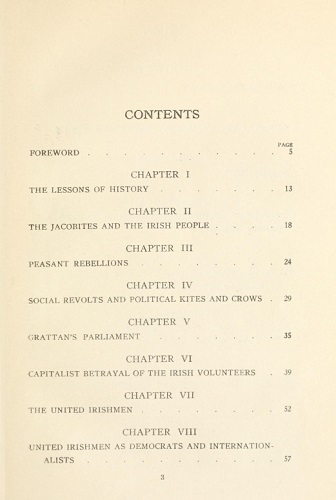

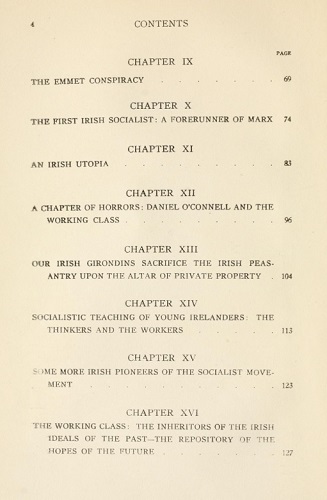

| sailed for USA, without his family, September 18, 1903, remaining until 1910; worked with The Socialist Labor Party on the east coast; joined by family, 1904 - and learns that his eldest dg. Mona has burnt to death in an accident; became Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) organiser, 1908; issued Socialism Made Easy (1909) and Labour, Nationality and Religion (1910), in reply to Father Kane, S.J., who delivered anti-socialist Lenten pastorals at Gardiner Street, 1909; fnd. Irish Socialist Federation in New York, attracting notice of William O’Brien;toured USA for 11 months, 1909-1910; issued Labor in Irish History in America (1910); returned to Ireland, arriving 26 July, 1910 | ||

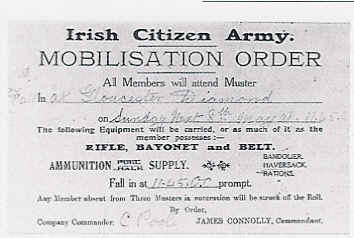

| assured of post in Socialist Party by O’Brien; given secretarial work under James Larkin of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ [ITGWU]; wrote Under Which Flag?, unprinted play; ed. The Harp; co-founded the Industrial workers of the World (“Wobblies”); was sent to Belfast on behalf of ITGWU, 1911, living at Glenalina Tce., off Falls Rd.; proposed foundation of Irish Labour Party at TUC meeting in Clonmel, 1912; led Irish Workers in Dublin when Larkin was imprisoned in 1913; responded to state brutally against strikers and demonstrators in Dublin Lock Out Strikg of 1912-13 approximately 250 strong Irish Citizen Army to defend the strikers; strikes end in defeat but set a precedent that would create better conditions and secure the rights of workers in Ireland; by forming the 250-strong Irish Citizen Army at Liberty Hall, with drillmaster Capt. J. R. [’Jack”] White - son of Field Marshal Sir George White, of Broughshane, co. Antrim; | ||

| warns British against a ‘carnival of reaction’ if compulsory recruitment was introduced in Ireland; fnd. the Irish labour Party, as political wing of the Irish Trade Union Council, 1912; met Winifred Carney who would become his secretary and accompanied him during the 1916 Rising;revived the Workers’ Republic on suppression of Irish Worker, Dec. 1914; formed Anti-War Committee after Redmond’s speech at Woodenbridge, Sept. 20, 1914, committing Labour movement to oppose recruitment and conscription, flying the banner, “We Serve Neither King Nor Kaiser, but Ireland” at Liberty Hall; attacked the remaining Irish Volunteers for inactivity; Workers’ Republic suppressed, 1915; Re-Conquest of Ireland (1915); became Acting General Secretary of Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU), 1915; Worker’s Republic asks, ‘Are we not waiting too long?’, Jan. 1916; | ||

| disappears for three days in Jan. 1916 (kidnapped by the IRB?], and shared in secret meeting with the Irish Republican Brotherhood which resulted in the decision to embark on the 1916 Rising with joint forces of the Irish Volunteers - controlled by the IRB - and the Irish Citizen Army; appointed military commander of Republican forces in Dublin [Dublin Brigade] by IRB Council, 1916; argued against occupation of Dublin Castle, as too straggling to defend and as containing Red Cross Hospital; appt. Commandant in GPO, Easter 1916; received multiple wounds and considered likely to live two days after arrest; held in a room of the State Apartments in Dublin Castle used for war-wounded [WWI]; sentence to death by court-martial; accepted Catholic last rites from Fr. Aloysius Travers of the Capuchin Order; urged his wife to convert to Catholicism at their last meeting (‘Hasn’t it been a full life, Lillie? And isn’t this a good end?’), asking his family to leave Ireland afterwards and seek friends abroad; executed by firing-squad tied to a chair at Kilmainham, 12 May 1916 [err. 9 May, DIH]; purportedly said of his executioners, ‘I will say a prayer for all men who do their duty according to their lights’; buried in a mass grave with other leaders, uncoffined and in quick-lime. | ||

| the Connolly Association was founded in Britain in 1938; The Testimony of James Connolly, was written and dir. by Eoghan Harris (RTE 1968); the National Library of Ireland holds his papers; a portrait-bust of him was erected in Troy, New York, 1988; a Dublin memorial by the sculptor Eamonn O’Doherty was planned for Beresford Place, Dublin, after a competition for the contract; “Labor & Dignity - James Connolly in America” an exhibition curated by Marion C. Casey, was mounted at Glucksman House (NYU) as part of Ireland’s Decade of Commemorations and its own 20th anniversary was toured to the TCD Library Long Room in Dec. 2013-Feb. 2014; a statue of Connolly by Steve Finney, cast in the Dublin Foundry, was unveiled by his grandson James Connolly Heron with the Minister of Culture, Caral Ni Chuilin, on the Falls Road, Belfast, in March 2016; Connolly is the subject of two commemorative poems by Sorley Maclean/Somhairle MacGill-Eain - one called ‘The Shirt of James Connolly’ based on the relic in the National Museum of Ireland. DIB DIH OCIL FDA | ||

| Monument to James Connolly at Beresford Place, Dublin sculpt. Eamon O’Doherty (1939-2011) |

|||||

|

|

||||

| Visited by his wife and daughter Nora in prison on 9 May 1916, shortly before his execution, Connolly asked if the socialist newspapers had taken notice of the Rising and said resignedly, ‘They will never understand why I am here. They will all forget I am an Irishman.’ (Quoted by Ray Burnett [in title and text] in Scotland and the Easter Rising: Fresh Perspectives on 1916, ed. Kirsty Lusk & Willy Maley, Luath 2016 - available online; accessed 22.01.2022.) |

[ top ]

Works| Published works |

|

| Collections & Editions |

|

| Correspondence |

|

| Newspapers edited by James Connolly (publication dates) | ||

|

|

|||

| 1894 | Party Politicians - Noble, Ignoble and Local (Labour Chronicle, 1 December) | ||

| 1896 | Irish Socialist Republican Party | ||

| 1897 | Socialism and Nationalism (Shan Van Vocht, January) ‘Patriotism and Labour (Shan Van Vocht, August) ‘Socialism and Irish Nationalism (L’Irlande Libre, Paris) ‘Erin’s Hope - The End & The Means (pamphlet) ‘Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee |

||

| [...] | |||

| —as attached. | |||

[ top ]

Bibliographical details

Collected Writings [3 vols], Vol. 1: William O’Brien, ed. & intro., Labour and Easter Week (Dublin: Sign of the Three Candles 1946); Vol. 2: Desmond Ryan, ed. & intro., Socialism and Nationalism: A Selection from the Writings of James Connolly (Dublin: Sign of the Three Candles 1948); Vol. 3: W. McMullen, intro., The Workers’ Republic (Dublin: Sign of the Three Candles 1951).

[ top ]

|

||

|

[ top ]

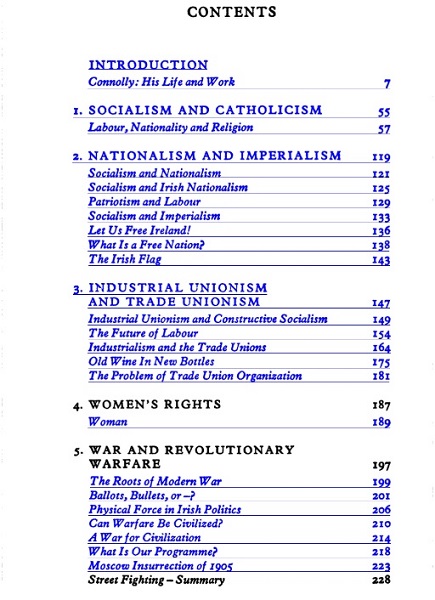

Peter Beresford Ellis, ed., James Connolly: Selected Writings (Harmondsworth: Penguin; NY: New Monthly 1973; London: Pluto 1997) |

|

|

|

| Pluto edition available at Google Books - online [accessed 01.05.2017 7 03.03.2023]. | |

[ top ]

|

|

[ top ]

Criticism

|

Bibiliographical details

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

Plays about Connolly: John Arden & Margaret D’Arcy, The Non-Stop Connolly Show, 5 vols.(Pluto Press 1977-78); Eoghan Harris, auth. & dir., The Testimony of James Connolly (RTE 1968); Terry Eagleton The White, the Gold, and the Gangrene, in Saint Oscar and Other Plays (Oxford: Blackwell 1997); Aindrias Ó Cathasaigh, James Connolly: A Working Class Hero, dir. by Brian O’Flaherty for Bruno Dog Productions (2013). Note: Connolly is a character in Gerry Hunt’s graphic novel [i.e., comic] about the 1916 Rising, Blood Upon the Rose (O’Brien Press 2009).

[ top ]

Commentary

P. Ó Cathasaigh [Seán O’Casey], The Story of the Citizen Army (1919). Chp. X: ‘Connolly Assumes Leadership’, incls. remarks: ‘Under Connolly’s leadership ... The [Volunteer’s] attitude of passive sympathy began to be gradually replaced by an attitude of active unity and co-operation. In their break-away from the Parliamentarian Party ...’ [51] ‘A well-known author has declared that Connolly was the first martyr for Irish Socialism; but Connolly was no more an Irish Socialist martyr than Robert Emmett [sic], P. H. Pearse, or Theobald Wolfe Tone.’ [52; see also under Sheehy-Skeffington, q.v.]. O’Casey was replaced as Secretary by J. Connolly [47]. Note that O’Casey wrote of a play by Connolly performed in Liberty Hall (26 March 1916), the script of which has been lost: ‘A play of his called Under Which Flag? blundered a sentimental way over a stage in the Hall in a green limelight, shot with tinsel stars.’ (Drums Under the Window [q.p.]; cited in The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing, 1991.)

W. B. Yeats: On 1913: ’Later that night Connolly carries in procession a coffin with the words “British Empire” upon it, and police and mob fight for its ownership, and at last, that the police may not capture it, it is thrown into the Liffey. And there are fights between police and windowbreakers, and I read in the morning papers that many have been wounded; some two hundred heads have been dressed at the hospitals; an old woman killed by batons blows, and or perhaps trampled under the feet of the crowd; and that two thousand pounds’ worth of decorated plate-glass windows have been broken. I count the links in the chain of responsibility, run them across my fingers, and wonder if any link there is from my own workshop.’ (Autobiographies, 195, p.368.)

Samuel Levenson, ‘James Connolly, Unquiet Spirit’, in Éire-Ireland, 6, 4 (Winter 1971), pp.110-17; Notes that Connolly was born in Edinburgh, his father working there as a garbage collector. Forced to leave school at age 10, Connolly worked in a tile shop, a bakery and a printing shop before becoming “too old” for such employment at age 14, whereupon he joined the British army. First saw Ireland as a member of the Second Battalion of the Royal Scots Regiment, stationed for two years at Cork, then 30 miles from Dublin, then in Dublin itself. In Dublin he met Lillie Reynolds, a domestic worker and an Anglican, and deserted, aged 21, to marry her. Settled in Irish slums of Edinburgh, working first as garbage collector, then opening a shoe repair shop to support an increasing family. Left Scotland for Ireland, 1896, spending seven years there working to establish an Irish Socialist Republican Party. Participated (with ISRP and Maud Gonne) in demonstrations against the 60th anniversary of Queen Victoria’s reign, and also the Boer War. Founded Workers’ Republic, the first of many radical publications, and ran for public office, prompting his opponents to pay for votes and threaten electorate with raised rents should he be elected. (p.112-113) Went to America in 1903 following disputes with his political comrades, writing bitterly, ‘Men have been driven out of Ireland by the British Government, and by the landlords, but I am the first to be driven out by The Socialists’. (p.114) Did not settle well, disliking the climate and much about American culture. Engaged in lengthy feud with De Leon (sometimes called the “’Marxist Pope’’), and had difficulty finding steady employment. Worked in Troy, NY, as an insurance salesman for Metropolitan Life, as a machinist in a Singer sewing machine plant in New Jersey and as a paid organiser for the Industrial Workers of the World and The Socialist Party. Established group of American Socialists of Irish origin and edited its publication, The Harp, later transferring its publication to Dublin. Returned to Dublin carrying texts for Labour in Irish History and Labour, Nationality and Religion. Became Belfast organiser of Irish Transport and General Worker’s Union, 1911, and helped found Irish Labour Party, 1912. Worked to combat the great Dublin Lockout, 1913, and stayed to rebuild the union when Jim Larkin left for America. Never spoke publicly against Larkin, despite their differences. (pp.115-16.) Built Irish Citizen Army in response to postponement of Home Rule Bill. (See descriptions of Connolly by sundry hands, quoted in idem.)

Francis Shaw, S.J., ‘The Canon of Irish History: A Challenge’, in Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review, LXI, 242 (Dublin 1972): ‘In Labour in Ireland, Connolly strove to show that all Irish revolutionary efforts had been socialist, and he was satisfied that the Gaelic mode of life was democratic; he apparently believed that the capitalist system had been introduced to Ireland by the [119] British, and that before that disaster there had been no private ownership of the land in Ireland.His book shows that some curious blooms can be grown most successfully in a vacuum.’ (pp.119-20.)

[ top ]

Tom Garvin, Irish Revolutionaries (Oxford: Clarendon Press 1987): ‘James Connolly, a somewhat isolated and unrepresentative figure among the revolutionaries, has had the effect of making the ideologies of the revolution appear retrospectively more egalitarian than they actually were. The fluence and occasional brilliancy of Connolly’s writings, combined with the new fashion for socialist ideas that emerged in the 1960s, have intensified this effect, as has the refraction of his ideas in Pearse’s later writings. Because both men became martyrs, they have been held to be representative’; in fact, both were to the left of the movement, and it would be difficult to say which was the further away from its centre of gravity [135] although in very different directions. Their prestige was so great that a mildly socialist flavour was given to the Democratic Programme of the first Dáil in 1919.’ (pp.135-56.)

David Cairns & Shaun Richards, Writing Ireland: Colonialism, Nationalism and Culture (Manchester UP 1988), remark: ‘Writing in the Irish socialists’ organ Forward, some months before the great Dublin lock-out of 1913, Connolly took up Marx’s fundamental statement that ‘[the] proletarian movement is the ... movement of the immense majority, in the interests of the immense majority’ and redefined it for contemporary Irish conditions. “Just as The Socialist knows that the working class, being the lowest in the social system, cannot emancipate itself without emancipating all other classes, so the Irish Catholic has to realise that he, being the most oppressed and disfranchised, could not win any modicum of political freedom or social recognition for himself without winning it for all others in Ireland” (quoted in Bernard Ransom, Connolly’s Marxism, Pluto Press 1980, p.24). ‘[...] The compulsion that would-be leaders were under to conform to certain unyielding requirements - Catholicism, familism and parliamentarism - ensured that just as in metropolitan-colonial relations the rules of discourse favoured the colonial power, within the people-nation the rules of discourse ensured the dominance of the parliamentarism of the UIL. / Connolly’s attempt to align socialist and Catholicism were augmented by his supportive gestures towards the members of the Gaelic League. In particular, in Labour in Irish History, he sought to produce a perspective in which, in keeping with the League’s enthusiasm, the ancient Gaels were seen as socially co-operative, holding property communally with democratically elected chiefs [of] society ideal in its time and only gradually destroyed by the Norman invaders.’ The authors further remark that Connolly’s view of Larkin’s experience convinced him that his approach was more likely to bear fruit. [96-7]. Of Connolly in 1900: ‘the man who is bubbling over with love and enthusiasm for “Ireland” and can yet pass unmoved through our streets and witness all the wrong and suffering, the shame and degradation wrought upon the people of Ireland, aye, wrought by Irishmen upon Irish men and women, without burning to end it, is ... a draud and a liar in his heart, no matter how he loves that combination of chemical elements which he is pleased to call “Ireland”’ (Selected Writings, ed. Peter Beresford-Ellis, 1973, p.38; here p.97.)

David S. Johnson & Liam Kennedy, ‘Nationalist Historiography and the Decline of the Irish Economy: George O’Brien revisited’, in Sean Hutton & Paul Stewart, eds., Ireland’s Histories: Aspects of State, Society and Ideology (1991): ‘[T]here was striking economic progress under Grattan’s Parliament was virtually an article of faith among nationalist writers [...] This belief has strong political resonance since it dovetailed neatly with contemporary economic arguments for Home Rule. Prevailing ideas on the subject were seriously questioned for the first time by Scottish-born socialist, James Connolly, in the course of a blistering attack on “parliamentarian historians”. In his highly original Labour in Irish History, published in 1910, he exclaimed, “The prosperity of Ireland under Grattan’s Parliament was almost as little due to that Parliament as the dust caused by the revolution of the coach-wheel was due to the presence of the fly who, sitting on the coach, viewed the dust, and fancied himself the author thereof.” (Three Candles ed., 1951, p.42). Connolly was sceptical of any gains in the living standards of the poor [...]. Not surprisingly, George O’Brien took issue with Connolly’s attempt to revise nationalist orthodoxy [in Ireland in the Eighteenth Century, p.406]. Connolly returned from American in 1910 with his pamphlet Socialism Made Easy. Connolly was at pains to oppose the total hostility to political (ie non-industrial) action that he had found among American syndicalists. He fought elections, supporting women’s right to the vote and Ireland’s right to independence. [...] Connolly and Frederick Ryan in the Independent Labour party of Ireland.’ (p.13-14.)

[ top ]

Emmet O’Connor, A Labour History of Ireland 1824-1960 (Gill & Macmillan 1992), remarks that the originality lies not solely in his conceptual framework but in specific points of interpretation as well, from his strictures on Connolly’s lack of views on the Irish Land question to those on the ITUC of 1894-1907 as nothing but a treacherous illusion. [thus quoted in The Irish Times, Jan. 1992.]

R. F. Foster, Paddy and Mr Punch (London: Allen Lane 1993), writes: ‘Connolly was a Marxist, but rather than completing capitalism’s contradictions, he wanted Ireland to revert t the purity of a pre-capitalist order and to rediscover the potential communal organisation which was, in his opinion, part of the Irish national psyche. A rupture with Britain would entail the rediscovery of social and economic innocence. Thus Connolly’s socialism is very closely linked to Gaelic Revivalism enabling him to see the peasants of the west as future soldiers in an economic class war –an unlikely prospect, looked at from any other angle.’ (p.90.)

Conor Cruise O’Brien, Ancestral Voices, Religion and Nationalism in Ireland (Dublin: Poolbeg 1994), writes of Connolly’s slipping under the influence of Patrick Pearse of whom he formerly called ‘nothing so new-fangled as a socialist or syndicalist [but] old-fashioned enough to be both a Catholic and a Nationalist’ in Oct. 1913. (p.113.)

Declan Kiberd, Inventing Ireland: The Literature of the Modern Nation (London: Jonathan Cape 1995), arguing that Connolly was right in seeing nationalism as a necessary preface to socialism in Ireland (along with Marx and Engels), and regards the delay of socialism as a consequence of the continuance of the national agenda under conditions of all-Ireland partition: ‘social revolution was prevented by a fixation upon the politics of partition’ (p.230).

[ top ]

Liam Kennedy, ‘The Union of Ireland and Britain, 1801-1921’, in Colonialism, Religion and Nationalism in Ireland (IIS/QUB 1996): ‘Connolly continues [in Labour in Irish History] his analysis by pouring scorn on the views of the ‘Parliamentary historians’ with respect to the supposed effects of increased absenteeism after the Union. The decline of the woollen and leather industries, for example, had far deeper causes. ‘Were the members of the Irish parliament and the Irish landlords the only wearers of shoes in Ireland?’ Why did British manufacturers continue to supply the Irish market, whereas the Irish manufacturers did not? Did the latter really have to ‘shut up shop and go to the poor house because My Lord Rackrent, and his immediate personal following had moved to London?’ (Collected Works, 1987, I, p.62.)

Liam Kennedy, Colonialism, Religion and Nationalism in Ireland (1996) - cont.: Connolly proceeds to argue the paradox that the weakness of Irish manufacturers was a cause, not a consequence, of the Union on the Marxist grounds that a strong capitalist class would have reformed the parliamentary system and extended the franchise. This would have produced an electorate and parliament that would never have agreed to the Act of Union; an interesting counterfactual hypothesis, though one begging a large number of questions. (&c.; p.57.) [Cont.]

Cont. (Kennedy, Colonialism, Religion and Nationalism in Ireland, 1996): Kennedy further notices that Connolly rejected Griffith’s protectionism (in ‘Sinn Féin, socialism and the nation’, Coll. Works, i, p.369), and quotes his ‘insufficient’ [Kennedy] explanation for Irish industrial decline in the nineteenth century that ‘Lots of important industries have disappeared from Ireland because Irish employers were encouraged’ by whom he does not say - ‘to refuse to treat their workers in a humane and reasonable fashion and so lost their trade to British competitors’. British capital had ‘grown up and had assumed the responsibility of the adult, but Irish capital is still immature and has all the defects of the “hobble-de-hoy”, not big enough to be a man and too big to be a boy.’ (‘Dublin Trade and Dublin Strikes’, in Coll. Works, ii, p.364-65.)

[ top ]

| See The Re-conquest of Ireland (1915; rep. 1917) in RICORSO Library, “Irish Classics” - via index or direct. |

End of Empire: ‘ [...] And what about the war? Well, I think it is the beginning of the end. This great, blustering British Empire; this Empire of truculent bullies, is rushing headlong to its doom. Whether they ultimately win or lose, the Boers have pricked the bubble of England’s fighting reputation. The world knows her weakness now. Have at her, then everywhere and always and in every manner. And before the first decade of the coming century will close, you and I, if we survive, will be able to repeat to our children the tale of how this monstrous tyranny sank in dishonour and disaster.’ (‘ The South African War, II’, in Workers’ Republic, 18 Nov. 1899 [link].)

World War I: ‘The war for civilization is waged by a nation like Britain which holds in thrall a sixth of the human race, and holds as a cardinal doctrine of its faith that none of its subject races may, under penalty of imprisonment and death, dream of ruling their own territories. A nation which believes that all races are subject to purchase, and which brands as perfidy the act of any nation which, like Bulgaria, chooses to carry its wares and its arms to any other than a British market. [...] Civilization cannot be built upon slaves; civilization cannot be secured if the producers are sinking into misery; civilization is lost if they whose labour makes it possible share so little of its fruits that its fall can leave them no worse than its security. [...] Truly, labour alone in these days is fighting the real war for civilization.’ (‘A War for Civilisation’, Workers’ Republic 30 Oct. 1915 [link].)

Pro-German: ‘The German nation is fighting a necessary fight for the saving of civilisation in Europe.’ (Quoted in Maurice Headlam, Irish Reminiscences (London: Robert Hale 1947), p.153 [see further - infra].

|

|

Bourgeois-nationalism: ‘If you remove the English army tomorrow and hoist the green flag over Dublin Castle, unless you set about the organization of The Socialist Republic your efforts would be in vain.’ (Selected Writings, ed. Peter Berrisford Ellis, NY & London: Monthly Review, 1973, p124.)

Cause and cure: ‘But deep in the heart of Ireland has sunk the sense of degradation wrought upon its people – a degradation so deep and so humiliating that no agency less powerful than the red tide of war in Irish soil will ever be able to enable the Irish race to recover its self-respect ... Without the slightest trace of irreverence but in all humility and awe, we recognise that of us, as of mankind before Calvary, it may truly be said, without the shedding of Blood there is no Redemption’ (quoted in Desmond Greaves, The Life and Times of James Connolly, pp.318-19; cited in Conor Cruise O’Brien, Ancestral Voices, Religion and Nationalism in Ireland, Dublin: Poolbeg Press 1994, p.113.)

Irish freedom: ‘The struggle for Irish freedom [he wrote] has two aspects: it is national and social. Its national ideal can never be realised until Ireland stands forth before the world a nation free and independent. It is social and economic, because no matter what the form of government may be, as long as one class owns as private property the land and instruments of labour from which all mankind derive their substance, that class will always have power to plunder and enslave the remainder of their fellow creatures.... The party which would lead the Irish people from bondage to freedom must then recognise both aspects of the long continued struggle of the Irish nation.’ (Connolly, Socialism and Nationalism, 1948; quoted in Peter Costello, The Heart Grown Brutal: The Irish Revolution in Literature from Parnell to the Death of W. B. Yeats, 1891-1939, Gill & Macmillan 1977, p.70.) Further, ‘A Resurrection! Aye, out of the grave of the first Irishman or woman murdered for protesting against Ireland’s participation in this thrice accursed war will arise anew the Spirit of Irish Revolution ... If you strike at, imprison or kill us, out of our graves we will evoke a spirit that will thwart you and, mayhap, raise a force that will destroy you.’ (Connolly, in Irish Worker, Dublin 19 Dec. 1914; Costello, op. cit., 1977, p.72 -noting resemblance to Pearse’s rhetoric.)

‘The Irish peasant in too many cases treated his daughter in much the same manner as he regarded a plough or a spade – as tools with which to work the farm ... growing up in this atmosphere the women of Ireland accepted their position of social inferiority [... //] The militant women, without abandoning their fidelity to duty, are yet teaching their sisters to assert their rights’ (Connolly 1914; cited in Rona M. Fields, A Society on the Run: A Pyschology of Northern Ireland, Penguin 1973).

The “epic of Dublin”: ‘When that story is written by a Man or a Woman with honesty in their hearts and with a sympathetic insight into the travails of the poor, it will be a record of which Ireland may be proud.’ (The Irish Worker, 28 Nov. 1914; quoted in W. P. Ryan, The Irish Labour Movement in the ‘twenties to Our Own Day, Talbot; Fisher Unwin 1919, p.234; cited in Godeleine Carpentier, ‘Dublin and the Drama of Larkinism, James Plunkett’s Strumpet City’, pp.209-17, p.209.)

Anglo-Irish Literature: ‘In the reconversion of Ireland to the Gaelic principle of common ownership by a people of their sources of food and maintenance[,] the worst obstacle to overcome will be the opposition of men and women who have imbibed their ideas of Irish character and history from Anglo-Irish literature. That literature, as we have explained, was born into the worst agonies of the slavery of our race, it bears all the birth marks of such origin in it, but irony of ironies, these birth-marks of slavery are hailed by our teachers as “the native characteristics of the Celt”! Hence we believe that this book attempting to depict the attitude of the dispossessed masses of the Irish people in the great crisis of modern Irish history, may justly be looked upon as part of the literature of the Gaelic revival’ (Labour in Irish History, p.6; quoted in Patrick Sheeran, The Novels of Liam O’Flaherty, Dublin: Wolfhound 1976, p.207.)

First Principles: ‘First that in the evolution of civilisation the progress of the fight for national liberty of any subject nation must, perforce, keep with the progress of the struggle for liberty of the most subject class of that nation [.../]. Second, that the result of the long drawn out struggle of Ireland has been, so far, that the old chieftainry has disappeared, or, through its degenerate descendants, has made terms with iniquity, and become part and parcel of the supporters of the established order; the middle-class, growing up on the midst of the national struggle, and at one time, as in 1798, through the stress of the economic rivalry of England almost forced into the position of revolutionary leaders against the political despotism of their industrial competitors, have now also bowed the knee to Baal, and have a thousand economic strings in the shape of investments binding them to English capitalism as against every sentimental or historical attachment drawing them towards Irish patriotism; only the Irish working class remain as the incorruptible inheritors of the fight for freedom in Ireland.’ (Labour in Irish History, p.8; quoted in Sheeran, op. cit. 1976, p.209.)

Politics of partition: ‘North and South will again clasp hands, again will it be demonstrated, as in ’98, that the pressure of a common exploitation can make enthusiastic rebels out of a Protestant working class, earnest champions of civil and religious liberty out of Catholics, and out of both a united social democracy.’ (Quoted in Peter Berresford Ellis, A History of the Irish Working Class, Pluto [1985] 1996, p.342; no source.)

Needs of the hour: ‘[W]e will have based our revolutionary movement upon a correct appreciation of the needs of the hour, as well as upon the vital principles of economic justice and uncompromising nationality.’ (Erin’s Hope: The End and the Means, 1897, p.25; quoted in Peter Kuch, ‘Writing Easter 1916’, in Transactions of the Princess Grace Irish Library Conference, May-June 1998.)

[ top ]

| Capitalism and the Irish Small Farmers (from The Harp, Nov. 1909) |

|

| —Available at Marxist.org - online; transcribed by the James Connolly Society [online], 1997; accessed 04.03.2020. |

[ top ]

Socialism & religion: ’In its march towards freedom, the working class must cheer on the efforts of those women who, feeling on their souls and bodies the fetters of the ages, have arisen to strike them off, and cheer all the louder if in its hatred of thraldom and passion for freedom, the women’s army forges ahead of the militant army of labour. But whosoever carries the outworks of the citadel of oppression, the working class alone can raze it to the ground.’ (Collected Works, Vol. 1, p.244.)

’Socialism, as a party, bases itself upon its knowledge of facts, of economic truths, and leaves the building up of religious ideals or faiths to the outside public, or to its individual members if they so will. It is neither Freethinker, nor Christian, Turk nor Jew, Buddhist nor Idolater, Mohammedan nor Parsee - it is only human. (Ibid., p.238.)

’Socialists are bound as socialists only to the acceptance of one great principle - the ownership and control of wealth-producing power by the state, and that therefore, totally antagonistic interpretations of the Bible, or of prophecy and revelation, theories of marriage and of history may be held by socialists without in the slightest degree interfering with their activities as such or with their proper classification as supporters of The Socialist doctrine.’ (Ibid., p.383-84.)

’For myself, though I have usually posed as a Catholic, I have not gone to my duty for 15 years, and have not the slightest tincture of faith left. I only assumed the Catholic pose in order to quize the raw freethinkers, whose ridiculous dogmatism did and does dismay me, as much as the dogmatism of the Archbishop. In fact I respect the good Catholic more than the average free-thinker.’ (Letter to John Matheson, 30 January 1908.) [The foregoing all quoted in Liam O Ruairc, ’Connolly on Religion, Sex and Dissent’, in The Blanket: A Journal of Protest and Dissent, 23 May 2003 [link].)

Religion reinstated: ‘Religion, I hope, is not bound up with a system founded on buying human labour in the cheapest market, and selling its product in the dearest; when the organised Socialist working class tramples upon the capitalist class it will not be trampling upon a pillar of God’s Church but upon a blasphemous defiler of the Sanctuary, it will be rescuing the Faith from the impious vermin who make it noisome to the really religious men and women.’ (The Harp, Jan. 1901; all cited in Kuch, op. cit., 1998.)

Anti-religion: ‘The Socialist Party of Ireland prohibits the discussion of theological or anti-theological questions at its meetings, public or private. This is in conformity with the practice of the chief Socialist parties of the world, which have frequently, in Germany for example, declared Religion to be a private matter, and outside the scope of Socialist action. Modern Socialism, in fact, as it exists in the minds of its leading exponents, and as it is held and worked for by an increasing number of enthusiastic adherents throughout the civilised world, has an essentially material, matter-of-fact foundation. We do not mean that its supporters are necessarily materialists in the vulgar, and merely anti-theological, sense of the term, but that they do not base their Socialism upon any interpretation of the language or meaning of Scripture, nor upon the real or supposed intentions of a beneficent Deity. They as a party neither affirm or deny those things, but leave it to the individual conscience of each member to determine what beliefs on such questions they shall hold.’ (Connolly, The New Evangel in Erin’s Hope: The End and the Means [1897] and The New Evangel: Preached to Irish Toilers [1901], intro. Joseph Deasy, Dublin & Belfast: New Books Publications 1968, p.33; cited in Peter Kuch, ‘Writing the 1916 Rising’, in Transactions of the Princess Grace Irish Library Conference, Whitsun 1998.)

The Irish Famine: ‘No man who accepts capitalist society and the laws thereof can logically find fault with the statesmen of England for their acts in that awful period. They stood for the rights of property and free competition and philosophically accepted the consequences upon Ireland; the leaders of the Irish people also stood for the rights of property and refused to abandon them even when they saw the consequences in the slaughter by famine of over a million of the Irish toilers.’ (Labour in Irish History, 1910; q.p.)

Easter 1916: ‘[...] Connolly came down the stairs and spoke to us on the landing. Putting his head close to mine, and dropping his voice he said, “We are going out to be slaughtered.” “Is there no chance of success?”, I said, and he replied “None whatever”.’ (Labour in Easter Week, [q.d.], p.21; cited in Léon Ó Bróin, Protestant Nationalists in Revolutionary Ireland, 1985, p.81.)

|

[ top ]

|

[ top ]

|

[ top ]

|

[ top ]

References

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 2, selects ‘Ireland Before the Conquest’, from Erin’s Hope (1896) [err. for 1897], pamphlet expressing idea of a form of primitive communism in pre-colonial Ireland [985-87], ‘Socialism and Revolutionary Tradition’, editorial from The Worker’s Republic, 26 June 1900, criticising a constant harkening back to the past [988-89], and notes [119, 211, 278, 512, 513, 702n, 807, 953, 954, 1019, 1023, 1026, 1134n. FDA3 selects Socialism and Nationalism, ‘Parnellism and Labour’; ‘Sinn Fein, Socialism and the Nation’; ‘North East Ulster’; A Continual Revolution; ‘A War for Civilisation’; ‘The Irish Flag’ [718-33]; BIOG [FDA3 810]. Bibliography lists Labour in Ireland [sic err. for Labour in Irish History (Dublin 1920 edn.); A Socialist and War 1914-1916 (London 1941); Labour and Easter Week (Dublin 1949); also Desmond Ryan, ed., Labour an Easter Week, Selected Writings of Connolly (1949); Boyle, The Irish Labour Movement in the Nineteenth Century (Wash: Cath. of America UP 1988), 384pp.; James Connolly, Workshop Talks (Cork Workers’ Club 1989), 20pp.; Connolly, William Walker, The Connolly-Walker Controversy on Socialist Unity in Ireland (Cork Workers’ Club 1989), 28pp; also Connolly, the Polish Aspect, a review of James Connolly’s political and spiritual affinity with Joseph Pilsudski leader of the Polish Socialist party organiser the Polish legions and founder of the Polish state (Athol 1989) [BNB 1989; no ISBN; Dewey 320.5]; R. L. McKenna, The Social Teachings of James Connolly (Dublin: CTS 1920); rep. Lambert McKenna, The Social Teachings of James Connolly (?1991).]

Emerald Isle Books (Cat. No. 95), lists Labour in Irish History (Dublin: Maunsel 1910), signed 1st edn. to a Belfast Protestant intellectual socialist [£50]; Towards the One Big Union: The Axe to the Root (Dublin: ITGWU 1934), new edn., 39pp.; Labour and Easter Week, ed. D. Ryan (Dublin: Three Candles 1949); Labour in Ireland, Labour in Irish History and The Reconquest of Ireland (Dublin: Three Candles n.d.); Labour in Ireland, intro. by Robert Lynd (Dublin: ITGWU 1944), 346pp.; The Worker’s [sic] Republic, ed. Desmond Ryan, intro. William McMullen (Dublin: Three Candles 1951); Socialism and Nationalism, intro. and notes by D. Ryan (Dublin: Three Candles n.d.).

University of Ulster Library (Morris Collection) holds Labour in Ireland; Labour in Irish History; The Reconquest of Ireland (Maunsel 1917).

Website: An extensive archive of his writings, mostly from Workers’ Republic is available at Marxist Writers Internet Archive [link].

[ top ]

Notes

Birthplace: Cowgate, as it was called, was a densely packed parish with 14,000 Irish immigrants, packed into horrific slum dwellings, inone tight square mile. In the Cow tenements (later the birthplace of Jarnes Connolly) where disease was rampant, more ’200 Irish lived on one stair, alongide pigs and goats. Not surprisingly, it was a hotbed of Fenian activity. (See Niamh O’Sullivan, ‘The Mystery of the Lost Painting [Aloysius O’Kelly’s Mass in a Connemara Cabin, 1883]’, in The Irish Times, Weekend, 2 Nov. 2002, p.6.)

Sketches: Joseph Holloway description of Connolly as ’a stout-built block of a fellow in a bowler hat. [...] There was a good deal of the Irish-American about him, and he looked a determined bit of goods.’ Louie Bennett, meeting him shortly before the Rising found him ‘utterly lacking in geniality ... dour and hard ... capable of deadly and merciless hatred’, although she admitted that he was one of the best speakers on behalf of women’s sufferage and women’s rights that she had ever heard. (Quoted in ibid., p.116.)

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn remembered ‘the pathetic picture that short, stocky, poorly clad, squint-eyed Connolly made as he stood outside Cooper Union in New York City selling copies of The Harp.’ (All quoted in Samuel Levenson, ‘James Connolly, Unquiet Spirit’, in Éire-Ireland, 6, 4, Winter 1971, pp.110-17 [as supra], p.16.)

Socialist Labor Party (USA): Wikipedia writes - ‘The Socialist Labour Party was a socialist political party in the United Kingdom. It was established in 1903 as a splinter from the Social Democratic Federation (SDF) by James Connolly, Neil Maclean and SDF members impressed with the politics of the American socialist Daniel De Leon, a Marxist theoretician and leading figure of The Socialist Labor Party of America. After decades of existence as a tiny organisation, the group was finally disbanded in 1980.’ (Available online; accessed 11.05.2019.)

We serve Neither King Nor Kaiser

[ The right-hand image enlarged on a a separate page - as attached ] Nora Connolly O’Brien [1]: Connolly’s daughter - Nora Connolly O’Brien - wrote biographical studies under the titles Portrait of a Rebel Father (London: Rich and Cowan; Dublin: Talbot 1935), rep. as James Connolly: Portrait of a Rebel Father, preface by Robert Lynd (Dublin: Four Masters 1975), 327pp., and We Shall Rise Again (London: Mosquito 1981).

Nora Connolly [2], James Connolly’s daughter, took over as Paymaster General for the Provisional Irish Republican Army when Margaret Skinnider was arrested and imprisoned for the possession of a revolver on 26 Dec. 1922. Connolly herself was arrested in 1923. (See Scotland and the Easter Rising: Fresh Perspectives on 1916, ed. Kirsty Lusk & Willy Maley ([Scotland:] Luath Press 2016) - Chronology; available on Amazon books - online; accessed 22.01.2022] Note: Skinnider was author of Doing My Bit for Ireland (1917).

Nora Connolly [3] - Letter to Mary Colum: There is a letter in the Berg Collection of the New York Public Library [NYPL], seemingly by a Miss N. Harvey, posted from an address at 79 Grosvenor Rd., Belfast and taken to be written by a relative of the recipient Mary Colum but actually by Nora Connolly, in which she speaks of plans to leave Ireland for America after her father’s execution and records, among his last words, his plea to his family to leave and live abroad among friends, asking Colum to contact their mutual friends in America to inform them of the family’s decision. (See Nicholas Allen, ‘A Turn-up for the Book in New York’ [“A Scholar’s Summer”], in The Irish Times, 8 Aug. 2009, Weekend, p.11.)

Roddy Connolly (1901-1980), Connolly’s son, was a lifetime member of The Socialist movement and Chairman of the Labour Party of Ireland, 1971-78. According to Charlie McGuire (Roddy Connolly and the Struggle for Socialism in Ireland, Cork UP 2007) he eventually sided with anti-Republican and anti-left elements in the working-class movement in Northern Ireland and was - ‘an activist who did make a considerable contribution to the struggle for socialism in Ireland, before ultimately leaving that struggle behind him’.

Seán O’Faoláin held Connolly responsible for ‘the grand delusion [of the] Gaelic mystique’. (Cited in Edna Longley, ‘Progressive Bookmen: Left-wing Politics and Ulster Protestant Writers’, in The Living Stream: Literature and Revisionism in Ireland, Newcastle-Upon-Tyne: Bloodaxe 1994, pp.112-13.)

Patrick MacGill writes of one Connoly [sic] who ‘gave his life for an ideal’, in his War-of-Independence novel, Maureen (London: H. Jenkins 1920).

Connolly Papers: National Library of Ireland holds collection of papers by and relating to Connolly, deposited by life-long friend William O’Brien [q.v.], Connolly’s successor as general secretary of the Irish Transport Worker’s Union.

[ top ]