Life

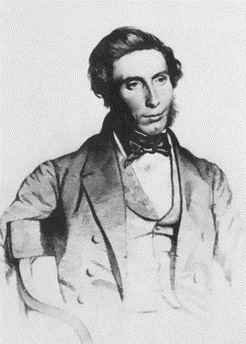

| [William Robert Wills Wilde; freq. Sir William R. Wills Wilde; occas. W. R. Wilde;] b. Kilkeevin, nr. Castlerea, Co. Roscommon, son of Dr. Thomas Wilde, with a practice in Castlerea [var. Castlereagh], Co. Roscommon; named Wills after a wealthy land-owning friend of the family; became an ENT [ear nose and throat] surgeon, being styled ‘father of Otology’; f. of Oscar; b. Castlerea, Co. Roscommon, ed. Elphin Diocesan School, Banagher (the school formerly principalled by Arthur Bell Nicholls, husband of Charlotte Brontë), and Dr. Steevens’ Hosp., where he qualified BM, 1837; |

|

||

| worked with Charles Lever to relieve patients of cholera epidemic in Connacht, reputedly performing an emergency trachotomy on a child with pocket-scissors; travelled as physician to the son of a rich Glasgow merchant to Mediera, Teneriffe, N. Africa and Middle East (‘The Holy Land’ and Turkey), both in search of health, on board Crusader; his account of his experiences, with details of meteorology, archaeology, and ethnology of the region, earned enough to provide his expenses for studies at Moorsfields Eye Hospital, London, with visits to Vienna, Berlin, and Heidelberg where he learned of scientific advances in ear, nose and throat [ENT] treatment, 1838-41; | |||

| issued an authoritative short work on the state of medicine in Austria; appt. member of the Irish Ordnance Commission, 1841; appt. Medical Commissioner to Irish Census, 1841, a post which he retained for the following census of 1851, collecting categories of information not included in other national censuses of the period; he formally greeted Prince of Wales (Edward VII), on royal visit of 1841; est. Molesworth St. Hospital in 1844, later set up St Mark’s Ophthalmic Hospital at his own expense in the then disused Park St. Medical School at Lincoln Place (rear of TCD; adj. Gt. Brunswick St.), later incorporated with Victoria Eye and Ear Hospital (Pembroke Rd.); his surgical reputation was built on his performance of the mastoiditis operation; | |||

| issued The Closing Years of Dean Swift’s Life (1849), much of the first portion having orig. appeared in Dublin Quarterly Journal of Medicine (1847); m. Jane Francesca Elgee [supra], 12 Nov. 1851; issued Irish popular Superstitions (1852), ded. to his wife; appt. ocular surgeon to Viceroy, 1853; the Wildes lived on Westland Row (now Pearse St.), where Oscar was born, before moving to 1, Merrion Square, at the Clare St. corner, where a literary salon presided over by Lady Wilde was conducted; ed. Dublin Journal of Modern Science, from 1854; played part in hosting British Assoc. for the Advancement of Science meeting, Dublin 1857; | |||

| visited by Baron von Kraemer, Gov. of Uppsala, who conducted an expedition to the Aran Islands at the same time; Sir William built a house in Co. Mayo, which he called “Moytura” as marking the scene of the legendary battle; he also owned a fishing lodge at Illaunroe, on Lake Fee, containing murals by Frank Miles showing the Wilde boys as fishing putti [Ital. figurative angels]; Sir William had access to the folios of Béranger’s sketches of Ireland; he received Swedish Order of the North Star at recommendation of von Kraemer, 1862; knighted by Victoria, 1864 [var. by Carlisle, 1861], for work on the Irish Census in which he provided exemplary data covering years including the famine period [viz., tables on Famine mortality]; lectured YMCA on “Ireland Past and Present: The Land and the People” (1864) - describing the present as a ‘the transition stage’, and urging that they were where ‘living under the mildest government in the world, a truly regal republic’; | |||

| involved in a suit instigated by his wife against Mary Josephine Travers, with whom he had an affair when she was an ear patient, 1854-60, and who wrote a pamphlet entitled Florence Boyle Price, or A Warning, portraying him as Dr. Quilp who rapes the title-character under chloroform; Travers - for whom Isaac Butt acted as counsel - received a farthing [var. ha’penny] damages, and costs of £2,000 against Wilde (12-17th Dec. 1864); Sir William retired from practice afterwards; issued a descriptive catalogue relating to Antiquities of Stone, Earthen, and Vegetable Minerals in the Museum of the Royal Irish Academy (1857), and another relating to [...] Antiquities of Gold (1862); his catalogue of Silver and Ecclesiastical Antiquities was issued by E. C. R. Armstrong in 1915); issued Lough Corrib, Its Shores and Islands (1867) - a lasting topographical classic; he coined the term ‘tymboglyphies’ for the engravings at Newgrange (Co. Meath); | |||

|

|||

| he was awarded the Cunningham Medal of the RIA in 1873, the year in which he visited Glendalough; addressed the Anthropological Section of British Association, Belfast 1874; d. 19 April, Dublin; bur. Mount Jerome; reputedly the ‘dirtiest man in Dublin’, causing Shaw to remark that Sir William was ‘beyond soap and water as his Nietszchean son was beyond good and evil’; illegitimately fathered a son, Henry Wilson (b. 1838), who later himself became an ophtalmologist trained by Wilde, and two girls (Emily, b.1847, and Mary, b. 1849), who were reared by his br. Rev. Ralph Wilde and who died tragically young [in a domestic fire]; his own funeral attended by one of the mothers with the acquiescence of his wife; heavily mortgaged estate paid off by his son Henry, to the benefit of Lady Wilde and Willie Wilde; a plaster bust of Wilde by an unknown hand is displayed in Royal Victoria Eye & Ear Hospital, Dublin; there is a Sir William Wilde ward at St. James Hospital, Dublin; the entry in Dictionary of Irish Biography (RIA 2009) is by Patrick Maume. DIB DIW DIH DIL OCIL | |||

[ top ]

Works

|

|

|

Also contrib. ‘Ireland-Past and present: the land and the people’ to Lectures Delivered before the Dublin Young Men’s Christian Association [...] during the year 1864 (Dublin: Hodges, Smith and Co. 1865) - as listed under Lord Dufferin, supra. |

| [ top ] |

| Reprints |

|

|

[ top ]

Criticism

|

|||

|

|||

|

[ top ]

Commentary

Sir Samuel Ferguson, ‘An Elegy on Sir William Wilde: 1876’: ‘Dear Wilde [...] the deeps close o’er thee and no more / Greet we or mingle on the hither shore ... Yet will affection follow ... Who loved thee living shall have also passed, - / This crumbling castle, from its basement swerved: / Thy pious underpinning skill preserved; / That carven porch from ruined heaps anew / Dug out, and dedicate by thee to view. Of wond’ring modern men who stand amazed / To think their Irish fathers ever raised / Works worthy of such care; this sculptured cross / Thou gatherest piecemeal, every knop and boss / And dragon-twisted symbol, side by side / Laid, and to holy teachings reapplied; / Those noble jewels ... Heirlooms of our Past, and all our own, / Or whether at despotic power’s command, they bow their beauty to a stranger’s hand ... Then, though unknown, thy spirit shall partake / Refreshment, too, for old communion’s sake.’ [End] (Poems, ed., A. P. Graves [n.d.; 1914], p.103.[ top ]

Eileen Battersby, ‘The surgical intellectul of the senior Wilde’, in The Irish Times (19th May, 2001), writes: Wilde first identified the tumulus a the bend of the Boyne as Brugh na Boinne in early Irish literature; identified crannog or lake-dwelling at Lagore, Co. Meath and researched it with Petrie; published his results in RIA Proceedings for 1841 though Petrie never finished his section; b. Castlerea, Co. Roscommon; son of Dr. Thom. Wilde (d.1838); apprenticed to Abraham Colles at 17; resident at Dr. Steevens; licenced Royal College of Surgeons, 1837; read paper on spina bifida to Medico-Philosophical Society as a student; traveelled in Med aboard Cruiser as physician to Robert Meiklam, a wealthy Scot; Narrative of a Voyage to Madeira [… &c.] (1840); shows constant awareness of hardships of the poor; moved to 15, Merrion Sq. on death of father (occurring in his absence) and was joined by mother and sister, 1840; eye clinic at rere of 11, Molesworth St.; move to abandoned almshouse in Mark St., later St. Mark’s Hospital; treated 1,000 patients by 1843; attendance at St. Mark’s compulsory from 1870; sole venue for aural surgery instruction in British Isles; devised Wilde’s forceps and Wilde’s angled snare; d. of mother, 1848; moved to 21, Westland Row; Speranza moved to read poems of Davis on witnessing his funeral; catalogued by classification 10,000 artefacts held by RIA, receiving Cunningham medal, 1873; libel case brought by Mary Josephine Travers; damages one farthing; Henry Wilson b. 1938; assisted Wilde at St. Mark’s; Emily and Mary, dgs., raised by his eldest br. Rev. Ralph Wilde; d. when dresses caught fire after party, 1871, aged 24 and 22; d. of Isola, 1867; one vol. of Gabriel Bd. of Isola, 1867; iss. one vol. of Gabriel Béranger’s ills., produced for B.’s patron William Brton Conyngham of Slane Castle; William Wilde, d. 19 April 1896. (p.8.)

Michelle McGoff-McCann, Melancholy Madness: A Coroner’s Casebook, foreword by Patrick McCabe [2004], relates: Emily and Mary Wilde, illegitimate dgs. of Sir William Wilde who were raised by his brother Rev. Ralph Wilde, attended a Hallowe’en ball at Drummaconor House in Co. Monaghan in 1871 and died in a fire accident; Emily’s crinoline caught fire at the hearth and when her sister came to her assistance hers ignited too; one of the girls was rolled in snow outside, the other ran in panic through the house; both died within a week of each other from severe burns; an inquest scheduled for 10 Nov. 1871 was commuted to an inquiry on the insistence of Sir William.

Rolf Loeber & Magda Loeber, A Guide to Irish Fiction, 1650-1900, Dublin: Four Courts Press 2006 [Intro.]: ‘Dr.William Wilde, father of the famous playwright and novelist Oscar Wilde, was consulted by poor patients from all over the island and, instead of a fee, collected folklore from some of them. Wilde then recast these stories, most of which were eventually published by his wife, Lady Wilde.’ (p.lii; citing B. Earls, ‘Supernatural Legends in Nineteenth-century Irish Writing’, in Béaloideas, LX-LXI, 1992-93, p.127.).

| —Available at London Review of Books - online; see also full-text copy - as attached. |

[ top ]

| Sir William Wilde looked forward to a time ‘When we have a novelist ... possessing the power of fusing ancient legend with the drama of modern life. Then and only then will Irish history be truly known and appreciated.’ (Irish Popular Superstitions, Dublin 1852, p.99; quoted in Thomas Wright, A Wilde Read: Oscar’s Books (London: Chatto & Windus 2008), p.25. |

| Note also that Sir William taught his son Oscar the Irish song ‘Tá mé ’mo chodladh is ná dúisitear mé’ - which is recited in full in Charles McGlinchey, The Last of the Name, intro. by Brian Friel (Belfast: Blackstaff Press 1986). See Wright, op. cit., p.23, and cf. McGlinchey, ‘The Fair at Pollan’, in RICORSO Library, “Irish Classics”, as attached. |

Irish Popular Superstitions (1852), ‘If ever there was a national that clung to the soil, and earned patriotism by the love of the very ground they walk on, it is the Irish peasantry’ (IUP edn., 1972, p.20); ‘There are certain types of superstitions common to almost all countries in similar states of progress or civilization, and others which abound in nearly every condition of society’ (p.30; quoted in Maria Pulida, paper in That Other World: The Supernatural and the Fantastic in Irish Literature: Transactions of the Princess Grace Irish Library Conference, 1998.]

Irish Popular Superstitions (1852): ‘It was really a sort of melo-dramatic exhibition. Those who wore cut paper round their hats, as wren-boys, when they grew up to be young men decorated themselves with ribbons and white shirts to act the May-boys - and, as mummers, painted their faces, and went through the Christmas pantomime with old rusty swords. These were the mechanists, stage-managers, wardrobe keepers, dressers, scene-shifters, and “property” manufacturers of the Roscommon Ribbonmen ... meeting, thus attired, with an old gun, or a yeoman’s rusty halbert, of a November night, and marching, by moonlight, to the sound of the fiddle or bagpipes, though what end was to be attained thereby, the great majority of them neither knew nor cared.’ (IUP edn. 1972, p.81; quoted in Luke Gibbons, Transformations in Irish Culture, Field Day/Cork UP 1996, p.18.)

Irish Popular Superstitions [1852] (Dublin: IAP 1979): In a ‘discursive introduction, written in 1849, and to be skipped by those who feel no present interest in Ireland’, he argued that the recent ‘great convulsion’ - ‘the failure of the potato crop, pestilence, famine, and a most unparalleled extent of emigration, together with bankrupt land pauperizing poor-laws, grinding officials, and decimating workhouses’ had ‘broken up the very foundations of social intercourse ...’, and that ‘The old forms and customs ... are becoming obliterated, the festivals are unobserved; and the rustic festivities neglected or forgotten ...’ (pp.9-11.) [Cont.]

Irish Popular Superstitions [1852; facs. rep. edn. IAP 1979): ‘In this state of things, with depopulation the most terrific which any country ever experienced, on the one hand, and the spread of education, and the introduction of railroads, colleges, industrial and other educational schools, on the other, - together with the rapid decay of our Irish vernacular, in which most of our legends, romantic tales, ballads, and bardic annals, the vestiges of Pagan rites, and the relics of fairy charms were preserved, - can superstition, or if superstitious belief, can superstitious practices continue to exist?’ (pp.14-15; both quoted in Diarmuid Ó Giolláin, Locating Irish Folklore: Tradition, Modernity, Identity, Cork UP 2000, p.17.)

Irish Popular Superstitions [1852] - On the effect of the Famine: ‘the great convulsions which society of all grades has lately experienced, the failure of the potato crop, and a most unparalleled extent of emigration, together with bankrupt landlords, pauperizing poor-laws, grinding officials, and decimating workhouses, have broken up the very foundations of social intercourse, have swept away the established theories of political economists, and uprooted many of our long-cherished opinions.' Further, remarks that '[t]he Shannaghie and the Callegh in the chimney corner, tell no more the tales and legends of the other days' and laments ‘the rapid decay of the Irish vernacular, in which most of our legends, romantic tales, ballads, and bardic annals, the vestiges of Pagan rites, and the relics of fairy charms were preserved which were ‘the poetry of the people, the bond that knit the peasant to the soil, and cheered and solaced many a cottier’s fireside.' Further: 'Everyone who can muster three pounds ten ... are [sic] on the move to America, leaving us the idle and ill-conditioned ..., so that it may well be said, the heart of Ireland now beats in America'. [48] (1852 Edn., pp.9-11, 21; quoted in Rolf Loeber & Magda Loeber, A Guide to Irish Fiction, 1650-1900, Dublin: Four Courts Press 2006, p.lviii.)

The Great Famine, ‘Two terrible calamities fell upon Ireland - famine and pestilence; and by these two dread ministers of God’s great purposes, the Irish race were uprooted and driven forth to fulfil their appointed destiny. A million of our people emigrated; a million of our people died under these judgements of God. Seventeen millions worth of the property passed from the time-honoured names into the hands of strangers. The echoes of the old tongue - call it Pelasgian, Phoenician, Celtic, Irish, what you will, still the oldest in Europe, is dying out at last along the stony plains of Mayo and the wild sea-cliffs of the storm-rent western shore. Scarcely a million and a half are left of people too old to emigrate, amidst roofless cabins and ruined villages, who speak that language now. Exile, confiscation, or death, was the final fate written on the page of history for the much-enduring children of Ireland. One day they may reassert themselves in the new world, or in other lands ... at the reverse side [of God’s providence] but have not yet turned the leaf.’ [SEE Lady Wilde (‘Speranza’), Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms and Superstitions of Ireland (London: Ward & Downey 1888); p.327]

The tally-stick: ‘[...T]he children gathered around to have a look at the stranger, and one of them, a little boy about eight years of age, addressed a short sentence in Irish to his sister, but meeting the father’s eye, he immediately cowered back, having to all appearance, committed some heinous fault. The man called the child to him, said nothing, but drawing forth from its dress a little stick […] which was suspended by a string around the neck, put an additional notch in it with his penknife. [We] were told that it was done to prevent the child speaking Irish; for every time he attempted to do so a new nick was put in his tally, and when these amounted to a certain number, summary punishment was inflicted upon him by the schoolmaster.’ (Quoted [in part] in David Greene, ‘The Founding of the Gaelic League’, in The Gaelic League Idea, ed. Sean Ó Tuama, Cork 1972, p.10; cited in Declan Kiberd, Inventing Ireland, 1995, p.143; also quoted [more fully] in Diarmuid Ó Giolláin, Locating Irish Folklore: Tradition, Modernity, Identity, Cork UP 2000, p.66.) [See also under notes, infra.]

Publish and ...: ‘Nothing contributes more to uproot superstitious rites and forms than to print them [...].’ (Quoted in Seamus Deane, ‘Fictions and Politics: The Nineteenth Century National Character’, in Gaéliana, VI (1984), p.97; rep. in Tom Dunne, ed., The Writer as Witness: Literature as Historical Evidence, Cork UP 1987.).

Peasant grievances (at breaking-up clachans): ‘the recollection of nights of social concourse, of aid in sickness, of sympathy in joy and sorrow, of combined operations of defence against bailiff or gauger’ (q. title, Dublin Univ. Mag., 41, 1853, p.20; cited in Estyn Evans, Irish Folk Ways, 1957, p.32.)

[ top ]

Library catalogues

Belfast Public Library holds W. R. Wilde, A Descriptive Catalogue of the Antiquities of Stone, Earthen, and Vegetable Minerals in the Museum of the Royal Irish Academy (Dublin: M. H. Gill 1857), 246pp.; also The Ethnology of the ancient Irish (Dublin: Kirwood and son 1844), 16pp.; An Inquiry into the Time of the Introduction and the General Use of the Potato in Ireland, and its various failures since that period (Dublin: M. H. Gill 1856), 19pp.; Loch Corrib, its Shores and Islands, with notices of Loch Measga. 4th ed., arranged and ed. by Colm Ó Lochlainn (Dublin: Three Candles 1955), 199pp. [first ed. 1867]; The Beauties of the Boyne, and its Tributary the Blackwater. 2nd ed. enlarged (Dublin: McGlashen 1850), 324pp; ill., maps. [1st ed. 1849]; also 2nd ed. rep. (Cork: Tower Books 1978), 324pp. [orig. 1850]; The Closing Years of Dean Swift’s Life; with remarks on Stella, and on some of his writings hitherto unnoticed. 2nd ed. revised and enlarged (Dubl: Hodges & Smith 1849), 184pp., front (port.); ills. [much of the first portion of this essay. orig. appeared in Dublin Quarterly Journal of Medicine 1847]; A Descriptive Cat. of the Antiquities of Gold in the Museum of the RIA by W. R. Wilde; with ninety wood engravings (Dublin: Hodges, Smith and Co. 1862) 100pp. [ills.]; Irish Popular Superstitions (Shannon: IUP 1972), 140pp; facs. rep. of 1st ed., 1852.Belfast Linenhall Library holds Catalogue of Antiquities in the Museum of the Royal Irish Academy, 1) animal materials and bronze, 2) gold, 3) stone.

Booksellers

Hyland Books (Catalogue 224) lists Wm. R. Wilde, Logh Coirib, Its Shores and Islands [3rd edn.], with an intro. by Colm O’Lochlainn (Three Candles Press 1938).

[ top ]

Notes

Tally stick (1): Wilde asked an Irish father ‘if he did not love the Irish language - indeed the man scarcely spoke any other’, and was told, ‘“I do”, said he, his eyes kindling with enthusiasm; “sure it is the talk of the ould country, and the ould times, the language of my father and all that’s gone before me - the speech of the mountains and lakes, and these glens, where I was bred and born; but you know”, he continued, “the children must have larning”, and as they tache [teach] no Irish in the National School, we must have recourse to this to instigate them to talk English.”’ (Quoted in Kevin Whelan, ‘Pre- and Post-Famine Landscape Changes’, in Cáthal Portéir, ed., The Great Irish Famine [Thomas Davis Lectures Series], RTÉ/Mercier, 1995, pp.31-32.)

Tally stick (2) - see also the paraphrase in Diarmuid Ó Giolláin, Locating Irish Folklore: Tradition, Modernity, Identity (Cork UP 2000): ‘When questioned, the father, who spoke little English, enthusiastically expressed his affection for the Irish language but explained that the children needed education and, since no Irish was taught in the schools, they had to be encouraged to speak English. The school was more than three miles distant, across river fords and over mountain passes, and an adult escorted the children there and back each day, occasionally carrying the weak.’ (Irish Popular Superstitions, [rep. edn.] IAP 1979, p.73.) Ó Giolláin goes on to remark that there is an account of a similar method in Ngugi wa Thiongo’s Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature (London: Heinemann 1986).

Famine deaths: Sir William Wilde’s tables on Famine mortality were challenged by Joe Mokyr (author of Why Ireland Starved), in a paper at International Conference on Hunger, New York 1995; reported by Luke Dodd, director of Strokestown Famine Museum, in Irish Reporter (Third Quarter, 1995), p.14.

Royal visit: William Wilde formally greeted Prince of Wales on royal visit of 1841 with an emblem in the form of a ‘Faith, Loyalty and Patriotism were happily combined in a large blue and red flag, having in the centre a green crown, containing a prince of Wales feather, and surmounted by an ancient Irish cross in gold. Below the banner hung an ancient Irish harp surmounted by an ancient spear.’ (See James Murphy, Abject Loyalty: Nationalism and Monarchy in Ireland During the Reign of Queen Victoria, Cork UP 2002; quoted by Lucille Redmond in review, Book Ireland, Dec. 2002, p.320.)

Note: John Peddubriwny has offered a correction by email of 29.04.23 casting in doubt the date of the visit of the Prince of Wales as given here - allowing that Edward VII - whose name had been added parenthetically by this editor [BS] - was born in Nov. 1841. In fact George IV visited Ireland for three weeks in 1821 (12 Aug.-3 Sept.) while Victoria visited with her consort Prince Albert in 1849 and returned without him (obiit) in 1853, 1861 and lastly in 1900, meeting with some hostility on the last occasion (“Famine Queen”). No royal visit occurred in 1841. The Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII, visited Ireland in April 1868 and later as king, accompanied Queen Alexandra, in July 1903. George V visited Ireland his coronation year, 1911. In 2011 Queen Elizabeth II visited the Republic of Ireland as guest of President Mary MacAleese - at the centenary of the last royal visit. Several Members of the Irish government and leader of the chief political parties including Sinn Féin attended the coronation of Charles III in May 2023, bringing to cycle of separation and reconciliation to something of a close. I have been unable to trace a solo-visit of the Prince of Wales other than that of Edward VII in 1868 - when Sir William was among the most eminent Irishmen of his time and some years before his death in 1875.

| Lady Wilde’s letter to the Dr Robert Travers, Assistant Keeper of MSS at Marsh’s Library and father of Mary Travers, dated 6 May 1864 - leading to the trial of 12-19th Dec. 1864: |

Sir - You may not be aware of the disreputable conduct of your daughter at Bray, where she consorts with all the low newspaper boys in the place, employing them to disseminate offensive placards in which my name appears ... As her object in insulting me is the hope of extorting money, for which she has several times applied to Sir William Wilde, with threats of more annoyance if not given. I think it right to inform you that no threat or additional insult shall ever extort money for her from our hands. The wages of disgrace she has so loosely treated for and demanded shall never be given to her. Jane F Wilde. |

| Isaac Butt, acting for Travers, brought a prior affair between Sir William and Travers into evidence rather than concentrating on the letter and the phase “wages of disgrace” which were particularly objected to; the court was swayed by Travers’s tendency to contradict herself, by quotations from her correspondence demanding money, and by allegations of laudanum addiction. Lady Wilde held to view that the supposed affair was the result of her hysterical imagination and dismissed the counter-accusation that she herself was conversant with it at the time. Travers won a farthing after 80 minutes deliberation by the jury. |

| [Quoted in an article by Eibhear Walshe printed in The Irish Times at the 150th anniversary of the ensuing trial. (Irish Times, Review Sect., 6 Dec. 2014.) See also note on The Diary of Mary Travers (Somerville Press 2103) - a novel - under Walshe, supra. |

|

| Mary Travers arriving at court ... | |

|

|

| —from Headstuff - online; accessed 26.12.2021. |

Gallantry: ‘As everybody knows, the [pitcher] can go to the well too often; and it was one of the “gallantries” of Sir William Wilde that, in Dec. 1864, was nearly to prove the undoing of himself and his wife’ ... [Mary Josephine] Travers v. Wilde and Another.’ Account given in Horace Wyndham, Speranza (1951) [For the chapter-contents of Wyndham’s book, see under Lady Wilde, supra.]

Yeatses: Sir William Wilde quoted as saying, ‘The Yeatses were the cleverest and most spirited people I ever met.’ (Frank Tuohy, Yeats, 1976, p.20.)

Synge Connection: In The Aran Islands (1907), J. M. Synge records a meeting with ‘and old dark man’ who recalls the visits of [George] Petrie, Sir William Wilde, and Jeremiah Curtin on Aranmore. (Introduction.)

[ top ]

|

| —Quoted in Ryan Fleming, [untitled] dissertation on Flann O’Brien, UU Coleraine, Jan. 2010. |

[ top ]

Bog butter: A partially destroyed wooden barrel with bog butter discovered at Mount Jubilee in Erris, Co Mayo is listed in William Wilde’s Descriptive Catalogue of the Antiquities in the Museum of the Royal Irish Academy (1857) [var. 1858]. His conjecture was that the burial was probably due to the intention to improve its flavour or perceived nutritional value while others have suggested ritual offering (Estyn Evans, 1946.) See R. C. Chapple, archaelogist, on the same or a similar vessel found at Mount Jubilee, Co. Mayo and held in the National Museum of Ireland - blog (7 Feb. 2012; accessed 09.12.2104). A line-drawing by Wilde is widely available on internet (e.g., Wikipedia, accessed 05.09.2011.)

Further, Regina Sexton refers to ‘William Wilde’s description of a roll of bog-butter stored inside a cylinder of wood [which is] illustrated in [P. W.] Joyce’s A Social History of Ancient Ireland’ (1920; rep. 1997, p.138) as evidence that ‘long rolls of butter were prevalent’ in the earlier period. She specifies the reference in Wilde as Catalogue of the antiquities of animal materials and bronze in the museum of the Royal Irish Academy (Dublin 1861, p.267) and also quotes Fergus Kelly (Early Irish Farming, 1997, p.328) who relates that butter was a part of land-rent in the medieval period. Kelly’s Guide to Early Irish Law (1988) is also cited. (See ‘The Role and Function of Butter in the Diet of the Monk and Penitent in Early Medieval Ireland’, in The Fat of the Land: Preceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cooking, ed. Harlan

Bibl.: W. R. Wilde, An Inquiry Into the Time of the Introduction and the General Use of the Potato in Ireland: And Its Various Failures Since that Period. Also, a Notice of the Substance Called Bog Butter (Dublin: M.H. Gill 1856), 19pp. - available at Google Books [online]; ‘On the introduction and period of general use of potato in Ireland with notice of the substance called bog butter’, in Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy 6 (1858), pp.356-72; cited in Chapple, op. cit. [online].

Sir Samuel Ferguson: Ferguson addressed a poem to “Dear Wilde”, rep. in Poems of Sir Samuel Ferguson, intro. A. P. Graves (Dublin: Talbot/London: R. Fisher Unwin [1917]), q.p.

[ top ]