| Life |

| 1821-1896 [née Jane Frances Agnes Elgee, aka Francesca; pseud. “Speranza”; diplomatically given as b.1826]; b. 27 Dec., in Wexford, dg. Archdeacon Charles Elgee (who died in India in 1824) and Sara Kingsbury, gd. of Dr Thomas Kingsbury, Commissioner of Bankrupts, in vicarage by the Bull Ring; gdg. of Rev. John Elgee, who was discomforted in the 1798 Rebellion [see note]; purportedly descended from Dante Alighieri via Algiati, Italian immigrants, but actually descended from Charles Elgee, one of two brother brick-layers [builders] from Durham who reached Ireland in the building-boom of the 1730s; her aunt Jane was married to Charles Robert Maturin [q.v.]; awakened to patriotism by reading poetry of Davis after having witnessed his funeral cortège in Dublin, 1845; contrib. poetry to The Nation, at first as John Fanshaw Ellis, from 1846; publishing her poem on the famine, “The Stricken Land”, in Nation (Jan. 23, 1847); assumed editorship of the Nation, 29 July 1848; wrote revolutionary editorials incl. “The Hour of Destiny”; accredited with authoring “Alea Iacta Est” [‘O!, for a hundred thousand muskets, glimmering brightly in the light of Heaven!’], a piece actually by Margaret Callan, sis.-in-law of Charles Gavan Duffy, leading to the suppression of the paper; |

| apocryphally said to have avowed authorship of the piece, charged to Duffy, from the the public gallery at his state trial, [July] 1848 (‘I am the culprit, if culprit there be’); 2 poems printed in Dublin University Magazine (1849); contrib. to Duffy’s Hibernian Magazine; issued trans. of Johann Wilhelm [var. Wilhem; Wildhelm] Meinhold as Sidonia the Sorceress (1849), and trans. of Lamartine’s History of the Girondins as Pictures of the First French Revolution (1850); also his Nouvelles Confidences as The Wanderer and his Home (1851); m. William Wilde (later Sir William [infra]), 12 Nov., 1851, honeymooning in Berlin, and visiting Denmark, from which representatives of the Royal Society of Northern Antiquities had visited Dublin the previous year; trans. Alexander Dumas’s Impression de Voyage en Suisse as The Glacier Land (1852); settled at Westland Row; a son William Charles Kingsbury Wilde, b. 26 Sept. 1852; a 2nd son, Oscar Wilde, b. 16 Oct. 1854 [infra]; remarked on his name, ‘Is that not a grand, misty and ossianic?’); |

| has a dg., Isola Emily Francesca, b. 2 April, 1857 (d. 23 Feb., 1867); moved to 1, Merrion Sq., 1858; Poems (Duffy 1864); conducted weekly at homes (or ‘conversazione’, Saturdays. 4-7 p.m.); defended her husband in Dublin civil action against accusations of rape under laudanum levelled at him by Miss Mary Travers, who purportedly dropped ‘nuisance letters’ in the door; costs of one farthing were found against Mrs. Wilde - author of the letter to her father which instigated the suit; publ. “To Ireland”, poem, in National Review, Sept. 1868; moved to London on her husband’s death in 1876 - on finding that he left her little money; settled at Ovington Place; came to be called ‘The Madame Recamier of Chelsea’; subject of encomium by her Oscar son in San Francisco, 1882 (reading out her “Trial of the Brothers Sheares in 1789”); received Royal Literary Fund grant, 1888 (stating her correct birthdate, as above); also received a Civil List pension of £300 [var. £70 p.a.] in recognition of her husband’s services to ‘statistical science and literature’, 1890, both grants being made through Oscar’s influence; greeted his novel Dorian Gray as the ‘most wonderful piece of writing in all the fiction of the day’; |

| contrib. “Historic Women”, a poem, to Oscar’s magazine Women’s World; also wrote a poem on Queen Victoria, approved by the Queen herself; wrote portions from Ancient Legends (otherwise called “Irish Peasant Tales”); retired to bed during Oscar’s first trial in 1895; advised him not to flee to the continent and sheltered him at her home, 146 Oakley Street, Chelsea, (where she had an Irish maid servant); contrib. Lady Wilde, “A New Era in English and Irish Social Life” to Gentlewoman, January 1883 issued works of folklore, Driftwood from Scandanavia (1884) and Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms and Superstitions of Ireland (1887), the latter incl. such stories as “The Child That Went Away with the Fairies”; supported in latter years by her son Willie from his salary on the Daily Telegraph; received gifts from C. G. Duffy and others; issued Ancient Cures, Charms and Usages of Ireland (1890); also issued Men, Women and Books (1891) and Social Studies (1893); she invited the suffragist Millicent Fawcett to her home to speak on women’s rights and corresponded with the Swedish feminist Lotten von Kraemer of Uppsala; unable to maintain subscription to Irish Literary Society, but retained as honorary member by the other members (see Irish Book Lover, XII, 1921, pp.126-28); contracted bronchitis, Jan. 1896; sought permission to visit her son in prison; |

| d. at home, 3 Feb. 1896; bur. anonymously in common ground within Kensal Green Cemetery, 5 Feb., the charges being paid for by her son Oscar, Willie being penniless; no headstone could be afforded; a Celtic Cross monument was later erected by the Oscar Wilde Society in 1999; a bibliography was published by James Coleman in Irish Book Lover, XX (1932); the obituary of her brother, a judge, appeared in Evening News (30 Nov. 1864); her letters to Lotten von Kraemer, held in National Library of Sweden, were published in 2008; the entry in Dictionary of Irish Biography (RIA 2009) is by Owen Dudley Edwards; Maud Gonne was hailed as “the new Speranza” who would do with her voice what the old Speranza did with her pen; her poem “The Famine Year” [as infra] was on the Irish school syllabus. ODNB IF NCBE DIB DIW DIH DIL PI MKA RAF JMC OCIL |

| Richard Ellmann: ‘Lady Wilde [...] had broken with her family’s Unionist politics by writing vehement poetry in support of the Irish nationalist movement. Her name was plain Jane, her pen name was Speranza, because of a high-flown genealogical fantasy that her family, the Elgees, were related to Dante’s family, the Alighieris. In writing to Longfellow, Dante’s translator, she signed herself Francesca Speranza Wilde. Later on she became less perfervid as a nationalist; she refused to read the proofs when some of her poems were republished, saying, “I cannot tread the ashes of that once glowing past.” But she remained immoderate. At her salon in Dublin, and later in London, she cut a figure in increasingly outlandish costumes, festooned with headdresses and heavy jewelry, and always capable of making extravagant statements. As her son commented later, “Where there is no extravagance there is no love, and where there is no love there is no understanding.” This must serve as a general defense for her conscious rhetoric, and his too. When she moved to London, and was asked about her poetry, she sighed, “My singing robes are trailed in London clay.” When someone asked her to receive a young woman who was “respectable,” she replied, “You must never employ that description in this house. Only tradespeople are respectable.”’ (‘Wilde at Oxford’, in The New York Review of Books (29 March, 1984) - online; accessed 02.04.2014.) |

| See under William Wilde for Lady Wilde’s letter to Robert Travers, the father of Mary Travers who took a suit against Lady Wilde and her husband in Dec. 1864 - as attached. |

|

|

|

||

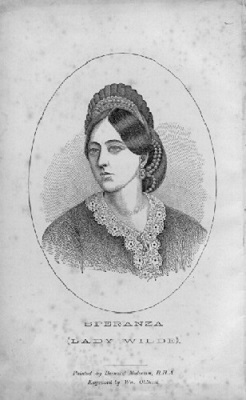

| Portrait by Bernard Mulrenin (RHA) | Frontispiece to Poems (1864) | Portrait by J Morosini (Dublin) | ||

|

||||

|

||||||||

[ top ]

Works| Poetry |

|

|

| Prose |

|

Also [qry.] The American Irish [2nd edn.] (Dublin: William McGee [1882]), [2], 47pp. [in assoc. with Walter Hamilton, 1844-1899 [British Library] |

See also R. A. Gilbert, ed., Irish Folklore and Mythology in the Nineteenth Century [Irish History & Culture, 6 vols] (Tokyo: Edition Synapse; London: Ganesha Pub. 2003- ), Vols. 1-2 [Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms, and Superstitions of Ireland; Ancient Cures, Charms, and Usages of Ireland]. Note: The publisher was formerly CIP. |

| [ top ] |

Bibliographical details

Poems by Speranza (Dublin: James Duffy 1864) [dedicated ‘to my Sons Willie and Oscar Wilde’, with the inscription, ‘I made them indeed/Speak plain the word country. I taught them no doubt/That a country’s a thing men should die for at need’; with title-page device showing her initials circled by buckled belt around which the words ‘Fidanza, Speranza, Constanza’, and commencing with ‘The Trial of the Brothers Sheares’]; &c. edns.]

Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms and Superstitions of Ireland ... To which is appended a chapter on “The Ancient Race of Ireland [extracts from the address to the Anthropological section of the British association, Belfast, ,1874, by Sir William Wilde]”, being pp.[329]-47, 2 vols. (London: Ward & Downey 1887, 1888), xii, 347pp., and Do. [... Contributions to Irish Lore] (London: [s.n.] 1890), xi, 256pp.; US edn. 1888); Do. [new edn.] (London: Chatto & Windus 1899, 1902, [1919], 1925), xxii, 347pp.; Do. [Ward & Downey Edn. of 1888] (Galway: O’Gorman 1971), xii, 347pp.; Do. [facs. of 1925 Edn.] (NY: Lemma 1973), and Do. [another edn.] (NY: Sterling 1991), and Do. [as] Legends, Charms and Superstitions of Ireland [Dover Celtic & Irish books] (Mineola, NY: Dover; Newton Abbot: David & Charles [distrib.] 2006), xii, 347pp. CONTENTS incl. Main section, pp.1-144 [numerous individual legends dealing with topics incl. fairies, the dead, curses, love-charms, Fenian knights, cave fairies, evil spells, festivals]; Legends of Animals [146-180]; [Medicine and super-stitions, 181-214]; Legends of the Saints [215-227]; Mysteries of Fairy Power [pp.228-235]; The Holy Wells [236-254]; Popular Notions concerning the Sidhe Race [256-271]; Sketches of the Irish past, [274-295, incl. Our Ancient Capital, 295ff]; Sir William Wilde’s ‘Ancient Races’, [329-47]. See also abbrev. sel. edn. as Ancient legends of Ireland Lady Wilde, compiled by Sheila Anne Barry (NY Sterling; London: [distrib. Cassell 1996), 128pp.

Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms and Superstitions of Ireland (London: Ward & Downey 1888), title page verso lists works by Lady Wilde: Driftwood from Scandanavia; Sidonia the Sorceress, from the German; Eritus Sicut Deus, or the First Temptation, from German, 3 vols.; The Glacier Land, from Dumas; The Wanderer and His Home, from Lamartine; Pictures from the First French Revolution; The future Life, Swedenburg; Poems, &c. &c.

See also Eibhear Walshe, ed., Selected Writings of Speranza and William Wilde (Clemson UP 2020), 256pp.

[ top ]

Criticism| Biographical studies |

|

See also sketches in C.J. Hamilton, Notable Irishwomen (Dublin: Sealy, Bryers and Walker, 1904) [espec. 176-7], and Harry Furniss, Some Victorian Women, Good, Bad, and Indifferent (London: John Lane 1923). |

Note that her son Oscar penned an anon. review of her folklore collections as part of ‘A Batch of Books’, which was rep. in Notes & Queries (Aug. 1983), pp.314-15; also in Reviews by Oscar Wilde (London 1908), pp.401-11 - noted in Thomas Wright, A Wilde Read: Oscar’s Books (London: Chatto & Windus 2008), pp.18-19. |

| General reading |

|

Bibliographical details

Horace Wyndham, Speranza: A Biography of Lady Wilde (London: T. V. Boardman & Co. 1951), 247pp. front. port. by Bernard Mulrenin RHA, engrav. W. M. Oldham. 12 ills. [incl. rep. of ‘Jacta alea est’ and ‘The American Irish’]. CONTENTS: Ring Up the Curtain; Politics and Poetry; Sounding the Tocsin; Doubles Harness; Dublin Days; Cause Celèbre; Change of Scene; Speranza’s Salon; Literary Flights; Fresh Fields; A Chelsea Recamier’ Speranza, the Last Phase; Appendices; index. Note referring to de Vere White’s Parents of Oscar Wilde, written in quotation marks on title page and in the hand of S. le Brocquy, ‘Lady Wilde is shown to be quite different from the comic butt which H. Wyndham made of her in his biography, Speranza’.

[ top ]

Commentary

William Carleton: Carleton referred to her as ‘the most extraordinary prodigy of a female that this country, or perhaps any other, has ever produced’, and highly praised her criticism in the Nation; she in turn advised him to write more cheerfully, to visit Paris [... &c.], writing also: ‘God and the world have done more for you than for millions - one gave you genius, the other gave you fame; and if you want lessons of noble feelings, of lofty, elevated, pure, unworldly sentiment, go to your own books for them.’ (Letter signed ‘Speranza’; quoted in O’Donoghue’s life of Carleton; cited in Benedict Kiely, Poor Scholar, p.159.)

Charles Gavan Duffy: ‘Her little scented notes, sealed with wax of a delicate hue and dainty device, represented a substantial force in Irish politics, the vehement will of a woman of genius.’ (Quoted in Horace Wyndam, Speranza: A Biography of Lady Wilde, London: T. V. Boardman & Co. 1951, p.29).

Oscar Wilde: ‘Of the quality of Speranza’s poem perhaps I should not speak – for criticism is disarmed before love – but I am content to abide by the verdict of the nation which has so welcomed her genius and understood the song, notable for its strength and simplicity, that ballad of my mother’s on the trial of the Brothers’ Sheares in ’98, and that passionate and lofty lyric written in the year of revolution called “Courage”. I would like to linger on her work longer, I acknowledge, but I think you all know it, and it is enough for me to have once had the privilege of speaking about my mother to the race she loves so well.’ (Quoted in H. Montgomery Hyde, Trials of Oscar Wilde (USA: Dover, 1973), pp.42-43; cited in Christine Kinealy, ‘“The Stranger’s Scoffing”: Speranza, the Hope of the Irish Nation’ [Paper given at Canadian Association for Irish Studies in Toronto, May 2008; revised for OScholars online - accessed 29.06.2011.)

W. B. Yeats: ‘Lady Wilde’s Ancient Legends is the most imaginative collection of Irish folk-lore, but should be read with Dr. Hyde’s more accurate and scholarly Beside the Fire. Lady Wilde tells her stories in the ordinary language of literature, but Dr. Hyde, with a truer instinct, is so careful to catch the manner of the peasant story-tellers [... &c.]’ (‘List of 30 Best Irish Books’, Dublin Daily Express, 27 Feb. 1895; in Wade, ed., Letters, pp.246-51; p.248).

W. B. Yeats: Mary Helen Thuente notes, ‘When Yeats included Croker’s “The Confessions of Tom Bourke” in Representative Irish Tales [1891], a selection which had also appeared in Fairy and Folk Tales, he appended a lengthy extract concerning the aesthetic, religious, and mysterious character of Irish fairy doctors from Lady Wilde’s Ancient Legends.’ (Thuente, Foreword to Representative Irish Tales, rep. edn., Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1979, p.17.)

Douglas Hyde: ‘Lady Wilde’s volumes, are, nevertheless, a wonderful and copious record of folk-lore customs, which must lay Irishmen under one more debt of gratitude to the gifted compiler. It is unfortunate, however, that these volumes are hardly as valuable as they are interesting, and for the usual reason - that we do not know what is Lady Wilde’s and what is not.’ (Beside the Fire [1898], Dublin: Irish Academic Press 1978 [facs. rep.], p.xix; quoted in Maria Pilar Pulido, ‘The Incursion of the Wildes into Tír-na-nÓg’, in That Other World: The Supernatural and the Fantastic in Irish Literature, Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1998.)

Benedict Kiely, Poor Scholar (1947; 1972), quoting her ‘famous laughable incitement to rebellion’ in the last issue of the Nation: ‘Gather round the standard of your chiefs. Who dares to say he will not follow, when O’Brien leads? Or who amongst you is so abject that he will grovel in the squalid misery of his hut, or be content to be flung from the ditch side into the living tomb of the poorhouse, rather than charge proudly like brave men and free men, with that glorious young Meagher at their head, upon the hired mercenaries of their enemies? One bold, one decisive move. One instant to take breath, and then [106] a rising - a rush, a charge from the north, south, east, and west, upon the English garrison, and the land is ours. Do your eyes flash - do your hearts throb at the prospect of having a country?’; Kiely remarks that this was part of the torrent of patriotic ink’ that his subject William Carleton condemned wisely enough in the Nation. (Kiely, op. cit., 1972 Edn., p.105-06). Note that her phrase ‘having a country’ echoes Davis’s speech to the Historical Society in TCD [see under Davis, infra.]’

[ top ]

Victoria Glendenning on ‘Speranza’, in Times Literary Supplement, 23 May 1980 [2 full pages], writes: The Athenaeum said that Speranza collected [at 1 Merrion Sq.] all those ‘whom prudish Dublin had hitherto kept carefully apart. Hers was the first and for a long time the only Bohemian house in Dublin’. [...] She has passionately wanted a girl for a second child and was once overheard saying that she had treated Oscar ‘for a whole ten years as if he had been her daughter; A Miss Henriette Cokran [sic, but cf. bibl. infra, Corkran] wrote down her impression of the Merrion Sq. salons [calling Speranza] ‘an odd mixture of nonsense with a sprinkling of genius’. There is a caricature of Speranza in the role of Mme Récamier in middle age by Harry Furniss. Sir William became involved with a patient, Mary Josephine Travers; old J. B. Yeats wrote to his son in 1921, recalling the ‘scandalous trial’, ‘I wonder what Lady Wilde thought of her husband’, and ‘On that occasion Lady Wilde was loyal.’ After ten years of sentimental friendship, Travers accused Sir William of violating her in his surgery; she proceeded to persecute the Wildes with letters to the press, pamphlets and broadsheets pushed through letter-boxes, demonstrations and placards in the street. Exasperated, Speranza wrote to her father ... Miss Travers took Speranza to court for destroying her reputation. The whole affair was spread over the Irish and English papers ... one sees the force of Frank Harris’s description of him as a ‘pithecoid person of extraordinary sensuality and cowardice.’ [Cont.]

Victoria Glendenning (‘Speranza’, TLS, 23 May 1980) - cont.: ‘In court, Speranza superbly said that she was ‘not interested’ in the intrigue, only in the nuisance; the trial resulted in an award of one farthing, and costs of £2,000 against the Wildes. Harry Furniss described the couple after the trial, ‘Lady Wilde, had she been cleaned up and plainly and rationally dressed, would have made a remarkable fine model of the Grande Dame, but with all her paint and tinsel and tawdry tragedy-queen get-up she was a walking burlesque of motherhood. Her husband resembled a monkey, a miserable looking little creature, who, apparently unshorn and unkempt, looked as if he had been rolling in the dust ... Opposite their pretentious dwelling in Dublin were the Turkish baths, but to all appearances neither Sir William nor his wife walked across the street ... at all the public functions these two peculiar objects appeared in their dust and eccentricity’. Sex did not play a large part in Lady Wilde’s life ... but she was loyal beyond duty [and] finished his memoir of the archaeologist Gabriel Beranger after his death [and] allowed a veiled woman, the mother of two of his natural children, to come daily and sit silently by his bedside while he lay dying ... No 1 Merrion Sq. was sold to his natural son Dr Henry Wilson. Katharine Tynan was a visitor at Park Lane in London. Max Beerbohm described Willie, ‘Quel monstre, dark, oil, suspect yet awfully like Oscar, he has Oscar’s coy, carnal smile and fatuous giggle and not a little of Oscar’s esprit. But he is awful - a veritable tragedy of family likeness.’

Victoria Glendenning (‘Speranza’, TLS, 23 May 1980) - cont.: Yeats recorded of the subsequent Oakley St salon, which Lady Wilde mistakenly kept open out of season, ‘the handful of callers contrasted mournfully with the roomful of clever people one meets there in the season’; yet this gave him an opportunity to hear her talk, ‘and London has few better talkers ... When one listens to her and remembers that Sir William Wilde was in his day a famous raconteur, one finds it in no way wonderful that Oscar Wilde should be the most finished talker of our time.’ D. J. O’Donoghue went to Oakley St in the last days, and commented on ‘the general tawdriness ... which that dimmed light failed to conceal ... And when ... later on, the crash came, everyone who knew them sympathised most with the mother, who was so inordinately proud of her son, and the expression one heard most frequently was “Poor Lady Wilde”’. When Oscar was arrested in 1895, Yeats called with sympathy and was greeted by a drunken Willie. During the trial, Oscar said, ‘My poor brother writes to me that he is defending me all over London; my poor, dear brother, he could compromise a steam engine!’ Yeats recorded Lady Wilde as saying, ‘If you stay, even if you go to prison, you will always be my son, it will make no difference to my affection, but if you go, I will never speak to you again.’ The essay quoted here is from Peter Quennell, ed., The Literary Salon in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries (Weidenfeld & Nicolson [1980]).

[ top ]

Patrick Rafroidi, ‘Speranza’s “Famine Year” [infra] made its way into the school textbooks in 1929, when it was included in Ballads of Irish History for Schools, where it would have left several generations of Irish school children with a millenarian interpretation of the Famine.’ Further [following quotation, as infra]: ‘Others like Speranza and John O’Hagan, settled back into a world of statisticians and statesmen which their poetry had earlier rejected.’ (Irish Literature in English, The Romantic Period, 1789-1850, Vol 1, 1980, Introduction, pp.30-31.) Note: Rafroidi cites a caricature by [Harry] Furniss.

Richard Ellmann, Oscar Wilde (1987), ‘from Algiati to Alighieri was an easy backward leap, and Dante could not save himself from being Jane Elgee’s ancestor.’ (p.5.); quotes Lady Wilde: ‘All virtue must be active. There must be no such thing as negative virtue.’ (Ellmann, 1987, p.8.) When you are as old as I, young man, you will know there is only one thing in the world worth living for, and that is sin.’ (ibid., p.13). [Note Wilde’s saying: ‘All women become like their mothers. That is their tragedy. No man does. That’s his.’

W. B. Stanford, Ireland and the Classical Tradition (1984), cites Speranza, ‘The Old Man’s Blessing’, ‘Let thy daring right hand free us/Lik that son of old Aegus,/Who purged his land for evermore/From the blood-stained Minotaur.’ Stanford’s bibl. references to Lady Wilde, The Spirit of the Nation, ed. WH Grattan Flood (Dublin 1911); also G.-D Zimmermann, Irish Political Street Ballads and Rebel Songs 1780-1900 (Geneva 1966).

Terence de Vere White, The Parents of Oscar Wilde (London:, Hodder & Stoughton 1967), p.234: ‘There was a point in her idealism and his enthusiasm where their natures met. It was established when she finished his unpublished work and included his last speech in her book of Irish customs, the harvest of his life’s gleanings shared with hers’.

Joy Melville, Mother of Oscar: The Life of Jane Francesca Wilde (London: John Murray 1994): ‘Oscar was only two and a half years old when Isola was born. Yet the rumour persisted in later years that, in her longing for a girl, Jane “caused” Oscar’s homosexuality by dressing him as a female when he was a child. The claim was first aired by an acquaintance, Luther Munday, who maintained that Jane told some guests at a party, and “not in a whisper either”, that, in her intense desire for a daughter, she treated Oscar “for ten whole years” as if he had been her daughter [...] in every detail od dress, habit, and companions.’ (p.68; quoted in Lynsey Turner, UG diss., UUC 2008.)

[ top ]

Brenda Maddox, review of Joy Melville, Mother of Oscar: The Life of Jane Francesca Wilde, in Times Literary Supplement (1 July 1994): her anti-British poetry took the form of ‘our murder[er]s, the spoilers of our land’; on leaving Dublin in 1878, she issued a blasting pamphlet called The Irish in America praising those who fled from the degraded position to which England had given Ireland in Europe; on the birth of her children, she wrote, ‘Alas! the Fates are cruel. / Behold Speranza making gruel.’ ‘Genius should never wed’. [See also review of same by Jerusha McCormack, in The Irish Times (18 July 1994).]

Merlin Wilde, Wilde Album (1997), on Lady Wilde’s Irish nationalism: ‘Lady Wilde as a youthful supporter of Irish nationalism, wrote patriotic verse for the Young Ireland journal, The Nation, under her pen-name of Speranza. Her famous editorials (written when the editor Charles Gavan Duffy was in prison in July 1848) called for a hundred thousand muskets and said that “the long-pending war with England has already commenced”. When Duffy was accused in court of writing this sedition, Speranza stood dramatically in the public gallery, saying, “I and I alone am the culprit, if culprit there be.” She was not prosecuted however, and Duffy was eventually set free. (Vide Declan Kiberd, ‘Irish Literature and Irish History’, in Roy Foster, ed., Oxford Illustrated History of Ireland, 1989, p.310; with charcoal sketch, signed J. H.) Holland casts doubt on the authenticity of this incident, and quotes Lady Wilde: ‘I was amused at that imputed act of mine becoming historical [...] . I shall leave it so – it will read well 100 years hence and if an illustrated history of Ireland is [15] published no doubt I shall be immortalised in the act of addressing the court.’ (p.16.)

Thomas Wright, A Wilde Read: Oscar’s Books (London: Chatto & Windus 2008) - on Lady Wilde, Ancient Legends: ‘The folk stories published by the Wildes comprise a teeming, grotesque and luridly coloured world. The chief protagonists are the little people, or the fairies, who are mischievous or malevolent, according to their mood or race. Sometimes they are content simply to upset a milk churn, but woe betide the farmer who takes away their dancing ground, because their retribution is swift and lethal. They take a devilish delight in stealing the most beautiful newborn babes and substituting them with demons. The only means of discovering if a child is a fairy changeling is the terrible trial by fire, in which the baby is thrown on to the flames. In one of the Wildes’ stories a child is hurled into a fire, where it turns into a black cat, then flies up the chimney with a terrifying scream. / It is a typically gruesome and bizarre episode from tales which articulate the very real fear of the fairies then still prevalent among the Irish peasantry and shared perhaps even by high-class Dubliners such as the Wildes.’ The tales record the fate of many children who have been carried off by the little people. They are usually whisked away to fairy palaces of pearl and gold, “where they live in splendour, and luxury, with music and song and dancing and laughter and all the joyous things, as befits the gods of the earth”. If the fairies are of the Sidhe race they transport their child captives to Tir na nOg, where they pass their lives in pleasure until Judgment Day, when they are annihilated.’ (p.20.)

Lean Culligan Flack, ‘“Cyclops”, Censorship, and Joyce’s Monster Audiences’, in James Joyce Quarterly (Spring 2011): ‘Don Gifford and Robert J. Seidman note that the melodies of Speranza (Lady Jane Wilde) were hardly plaintive but were rather nationalist and incendiary as in the case of her “upbeat celebration of “the martyr’s glory” in “The Brothers: Henry and John Sheares”. (p.444 [n.35], citing Gifford’s Ulysses Annotated, rev. edn., 1988,p.334.) [See text of “The Brothers” - infra.]

[ top ]

Quotations

“The Stricken Land”: ‘Weary men, what reap ye? - golden corn for the stranger. / What sow ye? - Human corpses that wait for the avenger. / Fainting forms, hunger-stricken, what see you in the offing? / Stately ships to bear our food away, amid the stranger’s scoffing.’ (Printed in The Nation, V, 224, 23 Jan. 1847, p.249; rep. in 1864 ed of Poems as ‘The Famine Year’; see Patrick Rafroidi, Irish Literature in English, The Romantic Period, 1789-1850, Vol 1, 1980, p.93.)

| “The Famine Year” | |

Little children, tears are strange upon your infant faces, No; the blood is dead within our veins—we care not now for life; |

We are fainting in our misery, but God will hear our groan: One by one they’re falling round us, their pale faces to the sky; |

| —First published in Nation (23 Jan, 1847), p.249; rep. in 1864 ed of Poems as ‘The Famine Year’; see Patrick Rafroidi, Irish Literature in English, The Romantic Period, 1789-1850, Vol 1, 1980, p.93. See also in Christine Kinealy, ‘“The Stranger’s Scoffing”: Speranza, the Hope of the Irish Nation’ [Paper given at Canadian Association for Irish Studies in Toronto, May 2008; revised for OScholars online - accessed 29.06.2011.) See further under Commentary, supra..) | |

A Proud Array: ‘There’s a proud array of soldiers - what do they round your door? / “They guard our masters’ granaries from the thin hands of the poor.“ / Pale mothers, wherefore weeping? - “Would to God that we were dead - / Our children swoon before us, and we cannot give them bread ....’ (quoted in P. J. Kavanagh, Voices in Ireland, 1994, p.109.)

A call to battle: ‘Gather round the standard of your chiefs. Who dares to say he will not follow, when O’Brien leads? Or who amongst you is so abject that he will grovel in the squalid misery of his hut, or be content to be flung from the ditch side into the living tomb of the poorhouse, rather than charge proudly like brave men and free men, with that glorious young Meagher at their head, upon the hired mercenaries of their enemies? One bold, one decisive move. One instant to take breath, and then a rising - a rush a charge from the north, south, east and west, upon the English garrison, and the land is yours. Do your eyes flash - do your hearts throb at the prospect of having a country?’ (Quoted in Benedict Kiely, Poor Scholar: A Study of William Carleton, 1947; 1972 edn., pp.105-06; citing no source.)

| “The Brothers: Henry and John Sheares. A.D. I798” | |

’Tis midnight; falls the lamp-light dull and sickly All eyes an earnest watch on these are keeping, They are pale, but it is not fear that whitens [...] |

[...] Ay; guard them with your cannon and your lances — Yet none spring forth their bonds to sever — Years have passed since that fatal scene of dying, |

| —For full version, see under Henry Sheares - supra. | |

[ top ]

Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms, and Superstitions of Ireland (London: Ward and Downey 1881): ‘In a few years such a collection would be impossible, for the olde race is rapidly passing away to other lands, and in the vast working-world of America, with all the new influences of light and progress, the young generation, though still loving the land of their fathers, will scarcely find leisure to dream over the fairy-haunted hills and lakes and raths of ancient Ireland. / I must disclaim, however, all desire to be considered a melancholy Laudatrix temporis acti. These studies of the Irish past are simply the expression of my love for the beautiful island that gave me my first inspiration, my quickest intellectual impulse, and the strongest and best sympathies with genius and country possible to a woman’s nature.’ (p.xii; cited Maria Pulido, paper given in That Other World: The Supernatural and the Fantastic in Irish Literature: Transactions of the Princess Grace Irish Library Conference, 1998 [publ. 1990].)

Ancient Legends, ... [&c.], 1881) - cont.: ‘The singular malefic influence of a glance has been felt by most persons in life; an influence that seems to paralyse intellect and speech, simply by the mere presence in the room of someone who is mystically antipathetic to our nature. For the soul is like a fine-toned harp that vibrates to the slightest external force or movement, and the presence and glance of some persons can radiate around us a divine joy, while others may kill the soul with a sneer or a frown. We call these subtle influences mysteries, but the early races believed them to be produced by spirits, good or evil, as they acted on the nerves of the intellect. (Lady Wilde, Ancient Legends [... &c..], 1889, [p.21], cited Ordhana Cassidy, UG Diss., UUC 1998.)

Ancient Legends, ... [&c.], 1881) - cont.: ‘The Irish, according to the saying of a wise man of the race, are the last of the 305 great Celtic nations of antiquity spoken of by Josephus, the Jewish historian; and they alone preserve inviolate and [?pure] the ancient venerable language, minstrelsy, and Bardic traditions, with the strance and mystic secrets of herbs, through whose potent powers they can cure disease, cause love or hatred, discover the hidden mysteries of life and death, and dominate over the fair wiles or the malefic demons.’ (‘The Properties of Herbs and their Use in Medicine’, ibid., p.181; cited Cassidy, op. cit.)

Ancient Legends, ... [&c.], 1881) - cont.: ‘To believe fantastically, trust implicitly, hope infinitely, and perhaps to revenge implacably - these are the unchanging and ineradicable characteristics of Irish nature ... And it is these passionate qualities that make the Celt the great motive force of the world, every striving against limitations towards some vision of ideal splendour.’ (ibid., pp.144-45; quoted in Mary Helen Thuente, ed. Yeats, Representative Irish Tales [rep. edn.], Colin Smythe, 1979, Foreword, p.11.)

[ top ]

Social Studies (1893): ‘Celtic fervour always finds its fullest expression in oratory and song. The Irish, especially, have a natural gift of copious and fluent speech. They are orators at all times, but under the influence of strong excitement they become poets, and in that story era, when every natuion was reading its rights by the flames of burning thrones, the Irish peots, mad with the magnificent illusions of youth, flashed their hymns of hope and defiance like a fiery cross over land and lake, over river and mountain, throughout Ireland, awakening souls to the like that they might have lain dead but for the magic incantation of their words.’ (p.272.) Further: ‘Yet the word country should be forever sacred, and lie at the base of all individual action and effort: for love of country is the divine corce that can alone war against the degrading tendencies of mere material gain: and no mental or moral elevation can be attained by a people who do not, above all, and before all things, uphold and reverence the holy rights of their Motherland.’ (idem.)

Ferguson’s Congal: ‘I have read and re-read and thought much over this poem. Congal seems to me to typify Ireland. He has the noble, pure, loving nature of his race – still clinging to the old, from instinctive faith and reverence, through ll the shadowy forebodings that he is fighting for a lost cause; and the supernatural here as a weird reality and deep significance; It is the expression of our presentiments. The pathetic beauty and interest of Congal’s career is heightened by the consciousness that he is fated, doomed [...] Yet he fights on, with the self-immolating zeal of a martyr, for the old prejudices of his nation, his fathers, his childhood, aginst the new ideas that overthrew all he reverenced. Still, all our sympathies are with Congal –with his suffering, the fated the wronged – for a beautiful nature underlies all. So it is with Ireland ... / The death of Congal, too, has a pathetic significance ... / Here again I find a symbolism to our poor Irish cause, always led by a hero, always slain by a fool.’ (Letter to Ferguson, in Sir Samuel Ferguson in the Ireland of His Day, 1896, II, 272-3; cited in Terence Brown, Northern Voices, 1975, pp.37-38; also quoted [in large part] in Welch, Irish Poetry from Moore to Yeats, Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe, 1980, p.151.)

Mayday: ‘Mayday in old times was the period of greatest rejoicing in Ireland, a festival of dances and garlands to celebrate the Resurrection of Nature, as November was a time of solemn gloom and mourning for the dying sun; for the year was divided into these two epoch, symbolising death and resurrection, and the year itself was expressed by a word meaning “the circle of the sun”, the symbol of which was a hoop, always carried in procession, wreathed with the rowan and the marsh marigold, and bearing suspended within it, two balls to represent the sun and the moon, sometimes covered with gold and silver paper.’ (Q. source; quoted in Sheila O’Sullivan, ‘W. B. Yeats’s Use of Irish Oral and Literary Tradition’, Heritage: Essays and Studies presented to Seamus Ó Duilearga, ed. Bo Almqvist et al., 1975, pp.266-79; cited in A. N. Jeffares, A New Commentary on the Poems of W. B. Yeats, 1984, p.54 - among remarks on “Song of Wandering Aengus”.)

| Anyone for Danish ...? |

|

| —Quoted in Michael Cronin, Translation in the Digital Age (Routledge 2013), p.23. |

Birthday girl: ‘There is no register of my birth in existence. It was not the fashion, nor compulsory in Ireland as it is now there is no dispute as to my legitimacy as daughter of Charles Elgee’ (ed in Joy Melville Mother of Oscar, John Murray 1994, p.58.)

Alea Iacta Est [the dice is cast] - Lady Morgan wrote of her moment at the trial of the Nation editors when she declared herself from the gallery to be the author of the offencig poem: ‘I think this piece of Heroism will make a good scene when I write my life, but the lession was useful - I shall never write sedition again. The responsibility is more awful than I imagined or thought of.’ (Letter to Scottish friend; Melville, 1994, p.38.)

Women’s Voices: Lady Wilde wrote to ‘Mr. Editor’ (her son Oscar) of Women’s World, signing herself La Madere Dolorosa, and complaining at her omission from review of Women’s Voices (anthology): ‘Why didn’t you name me in the review of Mrs Sharp’s books? Me, who hold such an historic place in Irish literature? And you name Miss Tynan and Miss Mulholland!’ (Ellmann, Oscar Wilde, p.277).

[ top ]

References

Patrick Rafroidi, Irish Literature in English: The Romantic Period, 1789-1850 (Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1980), Vol. 2, lists ‘The Madame Recamier of Chelsea’; first appeared in The Nation in 1846, publishing ‘The Stricken Land’ (V, 224, Jan. 23) in 1847, prior to the revolutionary editorials of 1848, ‘The Hour of Destiny’ and ‘Iacta Alea Est’, the latter responsible for the suppression of the paper; 2 poems in Dublin University Magazine [q. issue] (1849); Poems (Duffy 1864); Sidonia, The Sorceress, trans. [of] Wilhem Heinhold [sic] (1849); Pictures of the First French Revolution, trans. of Lamartine, History of the Girondins (1850); The Wanderer and His Home, trans. Lamartine, Nouvelles Confidences (1851); The Glacier Land, trans. A. Dumas, Impression de Voyage en Suisse (1852); Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms and Superstitions of Ireland with sketches of the Irish Past to which is appended a chapter on ‘The Ancient Races of Ireland’ by the late Sir William Wilde (London: Ward & Downey 1887); Ancient Cures (London 1890).

Christopher Morash, The Hungry Voice (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1989), b. Wexford, c.1824, d. London 3 Feb 1896; contrib. The Nation as ‘Speranza’, her article [sic] Jacta alea est’ responsible for the paper’s prosecution in 1848; m. William Wilde (knighted 1864); Poems (Dublin: James Duffy 1864); ‘The Enigma’, in The Nation vol. 6., No.293 (6 May 1848); ‘The Exodus’, in Poems (1864), p.43; ‘The Famine Year’, originally titled ‘The Stricken Land’ in The Nation, vol. 5 no. 224 (23 Jan 1847); ‘foreshadowings’, in The Nation, vol. 7, No. 3 (9 Sept. 1849); ‘France in ‘93, A lesson from Foreign History’, in The Nation vol. 5, no. 233 (27 March 1847); ‘A Lament for the Potato, A.D. 1739’ in Poems (1864), p.63; ‘A Supplication’, in The Nation, vol. 5 No. 272 (Dec. 18 1847); ‘The Voice of the Poor’ in The Nation, vol. 6, no 296 (13 May 1848); ‘Work While it is Called Day’, in The New Spirit of the Nation, ed. Martin MacDermott (1894), p.119. NOTE, other poems incl. one on the Sheares Brothers.

Belfast Central Public Library holds various eds. viz, Wilde, Jane Francesca, Ancient Cures, Charms and Usages of Ireland (London: Ward & Downey 1890), 256pp.; Ancient Legends of Ireland (Galway: O’Gorman Ltd. 1971), 347pp. [orig. 1888]; Ancient Legends, mystic charms & superstitions of Ireland, with sketches of the Irish past by Lady Wilde, new ed. (London: Chatto and Windus 1902), 347p.; also rep. (Galway: O’Gorman 1971), 347pp [1st ed. Ward & Downey 1888]; Irish Cures, Mystic charms and superstitions (NY: Sterling Pub. Co., 1991), 128pp.

University of Ulster Library (Morris Collection) holds Wilde, Jane Francesca (Elgee), Poems of Speranza (1871).

Hyland Books (Cat. 224) lists Ancient Cures, Charms and Usages of Ireland: Contributions to Irish lore (1890)

[ top ]

Notes

Sir William Wilde: The Nation (On 15th September 1849) contained a review article of William Wilde’s Superstitions, written by Miss Elgee (later Mrs. Wilde) while The book itself contained a quotation from her poetry.

Willie Wilde: Karl Beckson, reviewing Horst Schroeder, Additions and Corrections to Richard Ellmann’s “Oscar Wilde” (2002), xxi, in English Literature in Transition 1880-1920, 46, 4 (2003), points out a false attribution in Ellmann concerning Lady Wilde who was allegedly inspired by the birth of Oscar’s brother Willie to write: ‘Alas! The Fates are cruel. / Behold Speranza making gruel.’ According to Schroeder, citing Joy Melville’s biography of Lady Wilde (1994), ‘the doggerel was not of Speranza’s making, but was the brain-child of some visitor who saw her over her saucepans in the nursery.’ Beckson also quotes the corrected version of Max Beerbohm’s remarks on Willie: ‘Quel monstre! Dark, oily, suspecte yet awfully like Oscar: he has Oscar’s coy, carnal smile & fatuous giggle & not a little of Oscar’s esprit. But he is awful - a veritable tragedy of family-likeness.’ (Mary M. Lago & Karl Beckson, eds., Max and Will: Max Beerbohm and William Rothenstein: Their Friendship and Letters 1893 to 1945 (1975), p.21; all available at Schroeder’s website online, 22.03.2010.)

Thomas Carlyle: Oscar writes in De Profundis: ‘My mother, who knew life as a whole, used often to quote to me Goethe’s lines - written by Carlyle in a book he had given her years ago, and translated by him, I fancy, also:- “Who never ate his bread in sorrow, / Who never spent the midnight hours / Weeping and waiting for the morrow, / - He knows you not, ye heavenly powers.” / They were the lines which that noble Queen of Prussia, whom Napoleon treated with such coarse brutality, used to quote in her humiliation and exile; they were the lines my mother often quoted in the troubles of her later life.’

William Morris undertook the re-edition of Lady Wilde’s translation ‘which he praised as an almost faultless reproduction of the past, its action really alive.’ (Richard Ellmann, Oscar Wilde, London: Penguin Books 1987, p.19; quoted by Maria Pulido, in PGLIB Conference 1998.)

W. B. Yeats: Yeats quotes extensively Lady Wilde’s account from Ancient Legends of an old healer in the Island if Innis-Sark, in ‘Irish Fairies, Ghosts, Witches, &c.’, article in Lucifer [Theosophical Magazine] (15 Jan. 1889); see John P. Frayne, ed., Uncollected prose of W. B. Yeats, 1970, p.130ff; p.132-33.

James Joyce - see reference to Speranza in the “Cyclops” episode of Ulysses: ‘A posse of Dublin Metropolitan police superintended by the Chief Commissioner in person maintained order in the vast throng for whom the York Street brass and reed band whiled away the intervening time by admirably rendering on their black draped instruments the matchless melody endeared to us from the cradle by Speranza’s plaintive muse.’ (Bodley Head Edn., p.396.)

Anne Keary: ‘I shall begin to think you are the “Eva” or the “Speranza” who write pathetic treason in the Nation’. (Castle Daly, 1975, p.301.)

Robert Harborough Sherard, The Life of Oscar Wilde (London: T. Werner Laurie 1906), incl. rep. of ‘Iacta Alea est’. [Jacqueline Wesley Catalogue, 1993.]

Countess Anna de Brémont wrote of Lady Wilde’s dress, with family medallions attached to her bosom, that she ‘wore that ancient finery with a grace and dignity that robbed it of its grotesqueries.’ (Quoted in Barbara Belford, Bram Stoker, 1996.)

Iacta est alea - See Thomas Carlyle’s French Revolution - a source probably known to Lady Wilde: ‘Hussars clutch the Four National Representatives, and Beuronville the War-Minister; pack them out of the apartment; out of the Village, over the lines to Cobourg, in two chaises, that very night, - as hostages, prisoners; to lie long in Maestracht and Austrian strongholds! Jacta est alea.’ (French Revolution, Vol. III, Bk. III, Chap. VI, Chapman & Hall, n.d., p.125.) Note: The Latin phrase means ‘the dice is cast’.

Kith & kin (1): Rev. John Elgee: D. J. O’Donoghue writes of Rev. Henry Boyd (c.1756-1832): ‘[...] In 1798 he had to flee from the wrath of the rebels, and in his poems renews his hostility to them. One of them, “;The Recognition,” deals with an incident that occurred in Wexford during the insurrection to Rev. John Elgee (grandfather of the late Lady Wilde).’ (O'Donoghue, The Poets of Ireland, Dublin 1912, p.33.)

Kith & kin (2): Lady Wilde’s much older sister Emily Thomazine Algee m. Samuel Warren in 1839. Warren, a captain and later a lieutenant-col. in the British Army (like his brother Nathaniel), frowned on her sister’s politics. Her older brother became a judge in Louisiana. (See Richard Ellmann, Hamish Hamilton, Oscar Wilde, 1987, p.5.)

Portrait: There is a drawing by John Hughes, in a satirical vein, in the National Gallery of Ireland [see Oxford Illust. Hist., infra], and a caricature in ink of Sir William and Lady Wilde, shown in a dorsal view, by Harry Furniss. ‘Jacta Alea Est [the Die is Cast], or properly ‘Jacta est alea’, was coined in Suetonius, Lives of the Twelve Caesars, where it is attributed to Julius Caesar.

Brigitte Anton, ‘Women of The Nation,’ in History Ireland, 1, 3 (Autumn 1993), gives accounts of Ellen Mary Downing, with Mary Kelly (‘Eva’), Anna Francesca Elgee (‘Speranza’), Margaret Callan, née Hughes and Jenny Mitchel [née Verner].

Namesake: The case of James Zouch Esq: Thomas Collwell. John his eldest son Arnold his 2d. Ann married to the appellant. Lady Wilde ex par. Anne the wife of James Zouch plain. Agst. Collwell, Pilkington, & al. defend. Et Collwell & al. plaint. against Zouch & ux. def. [London : s.n., 1692], 1 sh. [being] The case of James Zouch Esq; appellant, the Lady Wild & al. respondents. To be heard on [blank] the [blank] of January instant. Imprint conjectured by cataloguer. ESTC R236018; not in Wing.

[ top ]