Skeffington & Joyce, Two Essays: “A Forgotten Aspect of the University Question” and “The Day of the Rabblement” (Dublin: Gerrard Bros. 1901).

[ Cover Details: Two Essays: “A Forgotten Aspect of the University Question” by F. J. C. Skeffington, and “The Day of the Rabblement” by James A. Joyce [2d.] (Dublin: Gerrard Bros. [37 Stephen’s Green] 1901), 8pp. [Skeffington, pp.3-6; Joyce, pp.7-8]. T.p. [p.1]: A Forgetten Aspect of the University Question / The Day of the Rabblement. Preface [p.2; as infra].

View this file in a separate window [Copies held in Buffalo Univ. Library and Croessmann Collection of Emory University, Georgia; copy in California University Libraries - prob. UCLA - available at Internet Archive > online.]

Ed. Notes: Each essay uses engraved initial letters for the first word occupying 3-4 lines and 1-line spacing between paragraphs. (See image of Joyce’s first page, infra.) There are several typographical errors in the printing of Joyce’s pamphlet, e.g., Byprison for Björgson and Trionfaute for Trionfante, D’Aununzio for D’Annunzio, and Turgeuieff for Turgenieff.

These pages are reproduced under James Joyce in the RICORSO Library of Irish Classics and all corrections and format alterations are primarily conducted there [as attached].

Note that the editors of the Critical Writings of James Joyce have attempted to facsimilise the original to the extent of introducing enlarged initial letters in the front position of each. The errata are not, however, reproduced or annotated. ]

Digital copy at University of California

available at Internet Archive - online.

These two Essays were commissioned by the Editor of St. Stephen”s for that paper, but were subsequently refused insertion by the Censor. The writers are now publishing them in their original form, and each writer is responsible only for what appears under his own name.

F. J. C. S.

J. A. J.

A Forgetten Aspect of the University Question

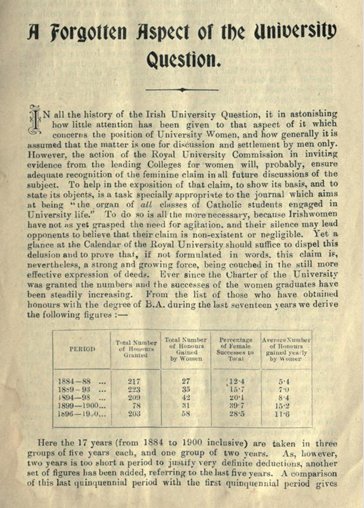

In all the history of the Irish University Question, it in astonishing I how little attention has been given to that aspect of it which concerns the position of University Women, and how generally it is assumed that the matter is one for discussion and settlement by men only. However, the action of the Royal University Commission in inviting evidence from the leading Colleges for women will, probably, ensure adequate recognition of the feminine claim in all future discussions of the subject. To help in the exposition of that claim, to show its basis, and to state its objects, is a task specially appropriate to the journal which aims at being “ the orsran of all classes of Catholic students engaged in University life.” To do so is all the more necessary, because Irishwomen have not as yet grasped the need for agitation, and their silence may lead opponents to believe that their claim is non-existent or negligible. Yet a glance at the Calendar of the Royal University should suffice to dispel this delusion and to prove that, if not formulated in words, this claim is, nevertheless, a strong and growing force, being couched in the still more effective expression of deeds. Ever since the Charter of the University was granted the numbers and the successes of the women graduates have been steadily increasing. From the list of those who have obtained honours with the degree of B.A. during the last seventeen years we derive the following figures :—

[Chart of Total Honours Gained and Honours Gained by Women, 1884-1900]

Here the 17 years (from 1884 to 1900 inclusive) are taken in three groups of live years each, and one group of two years. As, however, two years is too short a period to justify very definite deductions, another set of figures has been added, referring to the last five years. A comparison of this last quinquennial period with the first quinquennial period gives {3} some striking results. We see that while from ’84 to ’88 women graduates gained only 27 honours, or an average of 5.4 yearly, from 1896 to 1900 the average was 11.6 yearly. Comparing for the same periods feminine with masculine successes we find that in the first period the percentage of the number of honours gained by women to the total number granted was 12.4; it was 28.5 in the last quinquennial period. The table as a whole shows, moreover, that this remarkable increase is not sudden or abnormal, but steady and regular from the first appearance of women in the University lists to the present time. It cannot be imagined that this increase will suddenly be arrested, or that it will be possible on the initiation of a new regime to put an end to the intellectual ambitions of Irish girls; on the contrary, it is natural to think that the extension of educational facilities for their brothers will lead to an increased desire on their part to share therein. This desire must be satisfied, and it is therefore essential that in any settlement of the question women’s rights and privileges must be not only conserved but increased.

That they should be considered will, probably, not be denied by any but the most bigoted opponent, of women’s intellectual advancement, No one, we may well believe, would require women to forego the privileges which they have now possessed for twenty years. But it is possible that some might think it sufficient to leave them the Royal University as it stands; to perpetuate for the “inferior” sex that system of “education” by examining, not teaching bodies, which is rightly rejected as worthless in the case of men. It is well, therefore, that University women and those who sympathise with them should be on the alert, organised and prepared to combat and defeat any such makeshift proposal. Female as well as male students must have the full benefits of University life with regard to college buildings, college equipment, teaching, and, above all, that intercourse with fellow-students and with teachers, which is justly regarded as being, in its influence on character, the most valuable factor in the training afforded by Universities.

At this stage we may, perhaps, be met by the suggestion that a special Woman’s University would satisfy these requirements. It is not at all likely that the establishment of such an institution in Ireland would be found practicable under existing conditions; but for that very reason this solution might be put forward as the ideal one by those whose only desire is to shelve the question. Such a scheme, however, could never adequately provide for the University education of women. However objectionable the Royal “University”’ system may be in other respects, in the absence of any distinction of sex between suidents its precedent is most valuable and must be carefully followed. So much is this the case that, were Dubiin University altogether unimpeachable on any other score, its exclusion of women from any participation in its advantage would of itself prove it to be unfit to be a People’s University of the Twentieth Century.

Of course the Royal system of equal competition must be much extended and developed, as a necessary corollory to its reform in other directions While examinations were the only meeting-ground for students, equal freedom to enter for these examinations was as much as women could fairly expect; but when a genuine teaching University is established, all its privileges must be bestowed without distinction of sex; including the right to attend lectures (already granted to women by the Queen’s College, to their credit be it said,) admission to University societies, the right to {4} compete for all scholarships and prizes (here again the Queen’s Colleges show a praiseworthy example), eligiblity for Fellowships and Professorships, and proportionate share in the government of the University. As for buildings, the ideal University would be flanked by two residence-houses for men and women respectively; all the central portion (including lecture-halls, examination-halls, library, museums, laboratories, amusement-rooms), being the common field of all the students; the whole governed by a council chosen without distinction of sex, the female members of which would have special duties of supervision over the women’s residential college. At the head of the latter would be, probably, the most eminent lady-member of the Council.

Critics of the co-educative system are not wanting; but if we cast aside the prejudices and conventions of our semi-civilisation, its intrinsic superiority is apparent. The mischievous isolation of each sex throughout the long years of training for life, followed by the inevitable sudden plunge into each other’s society, is obviously unnatural, hostile to the development of character, and fraught with grave danger to morality. The separate system of education is a survival of the ages when the monastic ideal was deemed the only one praiseworthy; it is indeed a fitting prelude to a cloistered existence, but absurd as a preparation for the battle for life. As was well said by one of the speakers at the last International Congress of Women, “You cannot train for life if you deprive your pupils, at their most formative and receptive age, of all practical experience of that which is destined to be the strongest human force in life, the influence of sex on sex.” This was spoken with particular reference to co-education in secondary schools, but the principle here laid down is true of every stage of training. The two sexes, in equal and untramelled intercourse, exercise the strongest beneficial influence on each other; the predominant faults of each are restrained, the nobler qualities of both are fostered, and men and women of the best type are the result. Testimony to the value of co-education in the formation of character was borne at the Congress by delegates from Sweden and Norway, where the system is widely spread; and conservative alarmists may be assured, on the same testimony, that no evil results of any kind have followed from its adoption in those countries. The life of school and college is brought more closely into accord with the natural order the more it approximates to the conditions of a large family circle of brothers and sisters. And the logical outcome, of course, is that this association should be continued throughout the University course as well, in which respect a valuable lead has been given by many of the American Universities. It is not on behalf of women alone that the claim for co-education is made; for men also, this system is the only wholesome and natural one. Mentally and morally, the unrestrained companionship, the intellectual and social comradeship between man and woman which is thus produced cannot fail to redound to the advantage of both sexes and to the future well-being of the race.

To the ideal here put forward, however, many practical obstacles present themselves. There is the difliculty of finding a site for any University at all, much less for such a large double establishment; there is the objection that the co-educative principle, to be effective, ought to be introduced into our educational systems from the earliest to the latest stages, and not at one stage alone; there is the doubt whether Irish women would avail themselves of the privileges in sufficient numbers to {5} justify extensive endowments. The second objection has the most weight; for it is true that no country can be considered to have a first-class educational system unless the sex distinction is abandoned throughout. But no country possesses, as yet, this ideal system; even to take some steps towards its attainment may well content us. If the lack of women students in sufficient numbers should seem to forbid the establishment of special residential colleges for them, it might be advisable, as a first step, to treat the existing women’s colleges as “recognised boarding- houses,” where the students could also obtain tuition supplemental to that provided in the University lecture halls. In order to bring them into direct connection with the University these institutions could be supervised by a special sub-council, consisting, say, of the female members of the University Council, and such other ladies as they might co-opt. Further facilities could be granted gradually, as the natural increase of students made them necessary.

An important point for consideration is that in Dublin women students of all denominations have to be provided for. The non-Catholic students, however, would probably gravitate towards Trinity College, and eventually that masculine preserve will certainly be forced to drop the invidious sex- distinction and to recognise its inapplicability in intellectual regions. Meantime, we shall all rejoice to see the Catholic University of Ireland evincing in one more point its superiority to the moribund institution called “Dublin University.”

These suggestions are all made on the assumption that the present system is doomed, and that, whether through the Royal Commission or otherwise, a truly worthy University will arise in Dublin. However, while that consummation is yet delayed, those who have woman’s progress at heart should not be idle. Even within the Royal University much may be done. The refusal to appoint women to Senior Fellowships, when duly qualified, is a scandal which must be fought unsparingly. Victory in this point would be an important step towards securing a feminine element in the governing body, first of the Royal and afterwards of the new University. On the other hand, the admission, during the past two years, of women to certain lectures in University College is one of the favourable signs of the times which should be noted and appreciated. In a general way, there is work to be done in educating public opinion and preparing to take advantage of the change when it comes. For this, organisation is advisable. The Graduates’ Central Association might perhaps find it possible to add to its programme an assertion of women’s right to the preservation and increase of their present opportunities for University Education. But if this should not be feasible, then a separate organisation should be started, having this for its chief object. In such an association, of course, would include male supporters of the feminist movement; but the women graduates of the Royal University ought to take the main responsibility. It should be theirs to see that no carelessness is allowed to imperil the future advance of the sex, and to secure for Irishwomen such an equality in University culture as will enable them to accomplish worthily their due share in the regeneration of Ireland.

F. J. C. SKEFFINGTON.

[ top ]

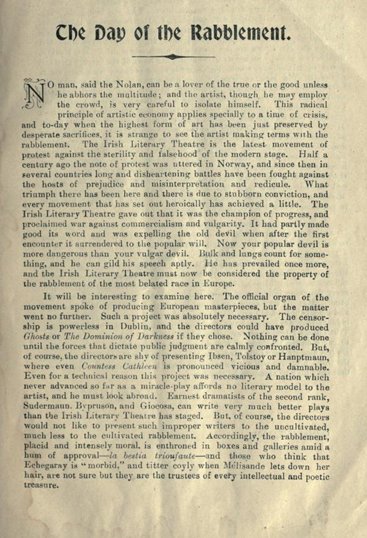

The Day of the Rabblement

No man, said the Nolan, can be a lover of the true or the good unless he abhors the multitude; and the artist, though he may employ the crowd, is very careful to isolate himself. This radical principle of artistic economy applies specially to a time of crisis, and to-day when the highest form of art has been just preserved by desperate sacrifices, it is strange to see the artist making terms with the rabblement. The Irish Literary Theatre is the latest movement of protest against the sterility and falsehood of the modern stage. Half a century ago the note of protest was uttered in Norway, and since then in several countries long and disheartening battles have been fought against the hosts of prejudice and misinterpretation and ridicule. What triumph there has been here and there is due to stubborn conviction, and every movement that has set out heroically has achieved a little. The Irish Literary Theatre gave out that it was the champion of progress, and proclaimed war against commercialism and vulgarity. It had partly made good its word and was expelling the old devil when after the first encounter it surrendered to the popular will. Now your popular devil is more dangerous than your vulgar devil. Bulk and lungs count for something, and he can gild his speech aptly. He has prevailed once more, and the Irish Literary Theatre must now be considered the property of the rabblement of the most belated race in Europe.

It will be interesting to examine here. The official organ of the movement spoke of producing European masterpieces, but the matter went no further. Such a project was absolutely necessary. The censorship is powerless in Dublin, and the directors could have produced Ghosts or The Dominion of Darkness if they chose. Nothing can be done until the forces that dictate public judgment are calmly confronted. But, of course, the directors are shy of presenting Ibsen, Tolstoy or Hauptmann, where even Countess Cathleen is pronounced vicious and damnable. Even for a technical reason this project was necessary. A nation which never advanced so far as a miracle-play affords no literary model to the artist, and he must look abroad. Earnest dramatists of the second rank, Sudermann, Bypruson [for Björgson], and Giocosa, can write very much better plays than tbe Irish Literary Theatre has staged. But, of course, the directors would not like to present such improper writers to the uncultivated, much less to the cultivated rabblement. Accordingly, the rabblement, placid and intensely moral, is enthroned in boxes and galleries amid a hum of approval — la bestia trioufaute [for trionfante] — and those who think that Echegaray is “morbid,” and titter coyly when Mélisande lets down her hair, are not sure but they are the trustees of every intellectual and poetic treasure. {7}

Meanwhile, what of the artists? It is equally unsafe at present to say of Mr. Yeats that he has or has not genius. In aim and form The Wind among the Reeds is poetry of the highest order, and The Adoration of the Magi (a story which one of the great Russians might have written) shows what Mr. Yeats can do when he breaks with the half-gods. But an esthete has a floating will, and Mr. Yeat’s treacherous instinct of adaptability must be blamed for his recent association with a platform from which even self-respect should have urged him to refrain. Mr. Martyn and Mr. Moore are not writers of much originality. Mr. Martyn, disabled as he is by an incorrigible style, has none of the fierce, hysterical power of Strindberg, whom he suggests at times; and with him one is conscious of a lack of breadth and distinction which outweighs the nobility of certain passages. Mr. Moore, however, has wonderful mimetic ability, and some years ago his books might have entitled him to the place of honour among English novelists. But though Vain Fortune (perhaps one should add some of Esther Waters) is fine, original work, Mr. Moore is really struggling in the backwash of that tide which has advanced from Flaubert through Jakobsen to D’Aununzio [for D’Annunzio]: for two entire eras lie between Madame Bovary and Il Fuoco. It is plain from Celebates and the latter novels that Mr. Moore is beginning to draw upon his literary account, and the quest of a new impulse may explain his recent startling conversion. Converts are in the movement now, and Mr. Moore and his island have been fitly admired. But, however, frankly, Mr. Moore may misquote Pater and Turgeuieff [for Turgenieff] to defend himself, his new impulse has no kind of relation to the future of art.

In such circumstances it has become imperative to define the position[.] If an artist courts the favour of the multitude he cannot escape the contagion of its fetichism and deliberate self-deception, and if he joins in a popular movement he does so at his own risk. Therefore the Irish Literary Theatre by its surrender to the trolls has cut itself adrift from the line of advancement. Until he has freed himself from the mean influences about him - sodden enthusiasm and clever insinuation and every flattering influence of vanity and low ambition - no man is an artist at all. But his true servitude is that he inherits a will broken by doubt and a soul that yields up all its hate to a caress; and the most seeming-independent are those who are the first to reassume their bonds. But Truth deals largely with us. Elsewhere there are men who are worthy to carry on the tradition of the old master who is dying in Christiania. He has already found his successor in the writer of Michael Kramer, and the third minister will not be wanting when his hour comes. Even now that hour may be standing by the door.

JAS. A. JOYCE.

Octoher 15th, 1901.

|

[ close ] |

[ top ] |