|

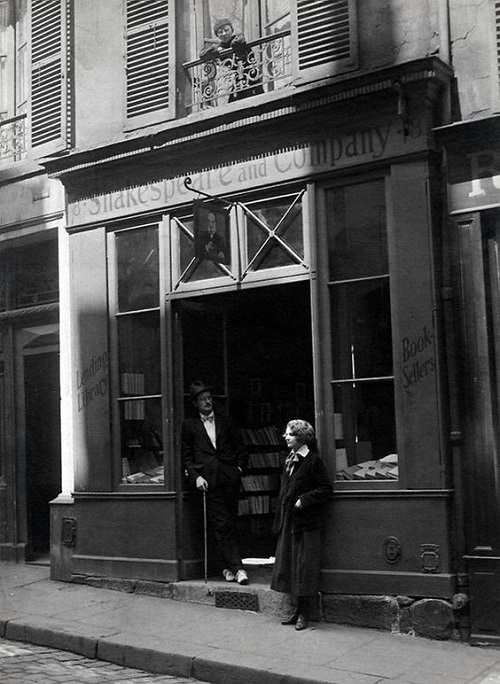

James Joyce and Sylvia Beach

at Shakespeare & Company (Paris)

Reflections on photographic records of Miss Beach’s famous shop

made by different hands in different periods

![Syvlia rue Duputyren [1919]](../jpegs/Duyptren/exterior/SylviaBeach1920.jpg)

|

|

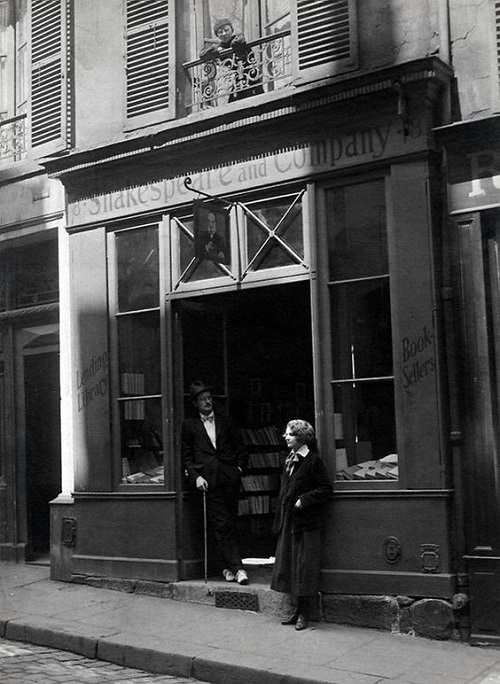

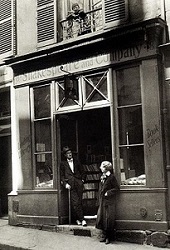

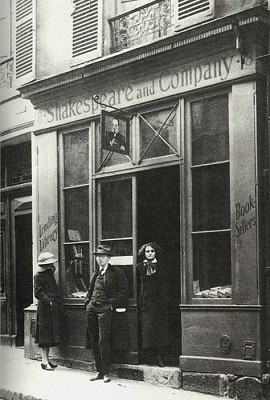

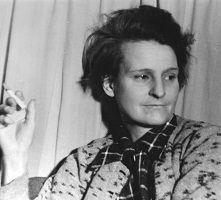

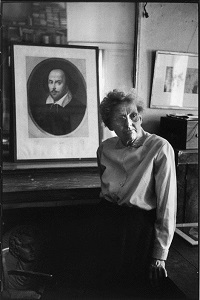

Syvlie Beach at 8, rue Dupuytren

Shakespeare and Company

(1956; Bison 1991),

facing p.108.

|

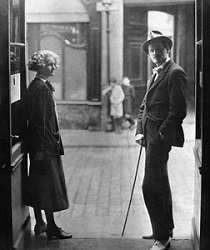

Syvlie Beach with James Joyce [left]

at

8, rue Dupuytren

[not included in

Beach, Shakespeare and Company].

|

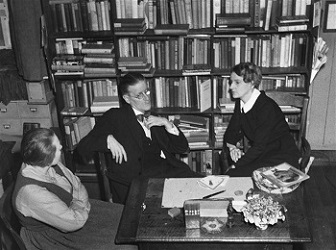

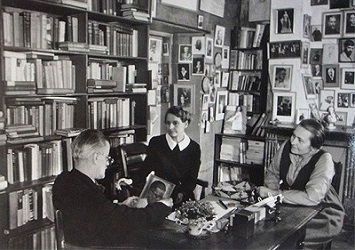

Sylvia Beach and James Joyce in Shakespeare and Company (Paris) |

|

|

|

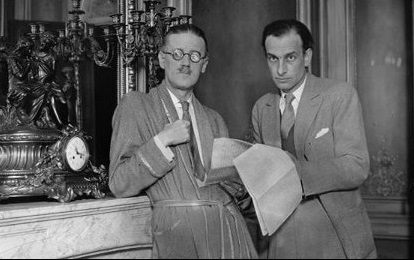

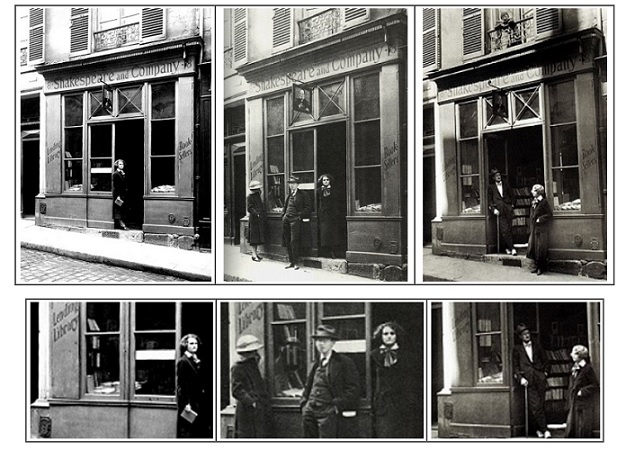

Left: Joyce, Beach John Rodker & Cyprian Beach, photo of Alliance Paris, in Beach, op. cit., 1956, No.14 [loc. not stated]. Right: Beach at same venue - Buffalo Collection [9222].*

|

|

Left & Right: Joyce with Sylvia Beach at 8 Rue Dupuytren, 1921 (photographer unknown) [See Notes - infra - dating this with the others as having been taken in 1920.

|

|

|

|

|

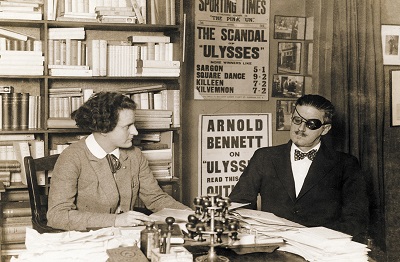

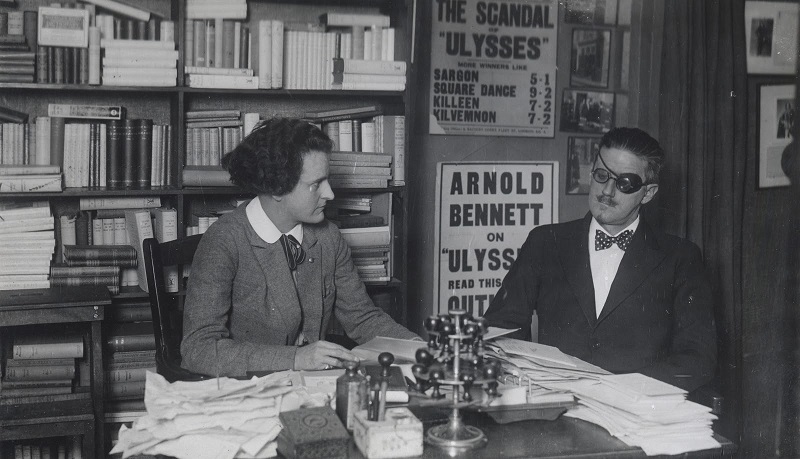

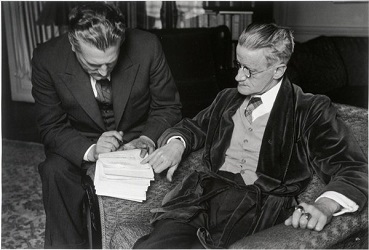

Joyce with Sylvia Beach at 12 rue de l’Odéon - 1922

known by the “Scandal of Ulysses” poster [sepia].†

|

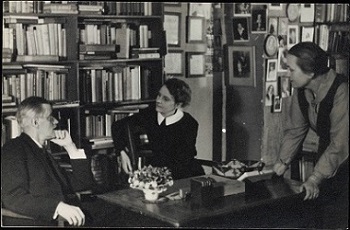

Joyce with Beach and Adrienne Monnier - 1938

(photo by Gisèle Freund).

|

|

|

| Joyce with Sylvia Beach at 12 rue de l’Odéon - known by the “Scandal of Ulysses” poster [

b&w]; see as attachment).† |

|

*The photo of Joyce and Beach with Cyprian Beach (left) and John Rodker (right back) is held in the James Joyce Collection of Buffalo University [Lockwood] Library] and dated ‘à Shakespeare and Company en 1921’. (See online as item 9222.) It is not said that the photo was taken at rue Dupuytren, as I infer in this notice - though the position of the desk and the items seen on it strongly suggest a different venue from the photos known to have been taken at 8 rue Dupuytren in 1920 - if most likely the same table. |

†The “Scandal of Uysses” photo is stated in the Buffalo UL catalogue to have been taken in Feb. 1922. In remarks therein the four pictures on the wall behind a seated Joyce to the right of the “Scandal” poster [see detail, supra] are also attributed to the New York Times [sic] as having been taken at 8 rue Dupuytren in 1920 & 1921. These are elsewhere identified - with more probable truth - as ‘anonymous’. The Buffalo Catalogue notice reads as follows:

On verso in SB’s handwriting “Photo by New York Times of James Joyce & Sylvia Beach | at Shakespeare and Company bookshop 12 rue de l’Odéon Paris 1922 | Behind Joyce: 2 posters from London 1) announcing |write-up of Ulysses in ‘Sporting Times’ (Feb. 1922) and 2) | Arnold Bennett’s article in the “Outlook” Feb 1922 | Behind Joyce on the right: 4 photos by New York Times | of 1) James Joyce and Sylvia Beach at Shakespeare and | Company 8 rue Dupuytren Paris (former premises) 1920 | 2) same in doorway 3) interior with James Joyce: | Sylvia and Cyprian Beach and John Rodker | In right upper corner: 2 photos of Wilde framed | with autograph letters of Wilde- gifts to |Shakespeare and Company of Byron Kuhn “Count | Prorok”; Shakespeare and Company stamp; photograph torn and taped.

An enlargement of the 1922 picture mentioned here can be view as attached. Note, however, that the original is torn or cracked and repaired with tape [Available at the Buffalo Library James Joyce Collection - Catalogue vii - online; latest revisit 11.07.2021]. |

| |

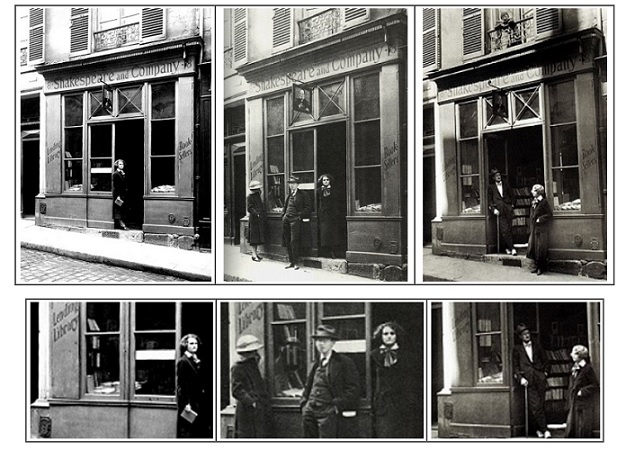

The four photos of Shakespeare and Company taken at Rue Duputryen which are included in the 1922 Ulysses photo of Feb. 1922.

|

|

|

Note that above four images above are those on the wall at Shakespeare and Company at rue de l’Odéon as seen in the “Scandal of Ulysses” photo of Feb. 1992 attributed to the New York Times. There are here arranged horizontally and copied in their original form with the Buffalo Library overprint. The photos are now held in the Buffalo University Library James Joyce Collection and catalogued with notes as to provenance (mostly via Beach). Of the first shown here, showing Joyce and Miss Beach in the doorway as taken from the interior of the bookshop, the Catalogue reads: ‘Inserted note in SB’s handwriting “Sylvia Beach James Joyce | à Shakespeare and Company | 8 rue Dupuytren | en 1921 | (publication de Ulysses en train)” - online; accessed 11.07.2021.’ |

|

|

| |

|

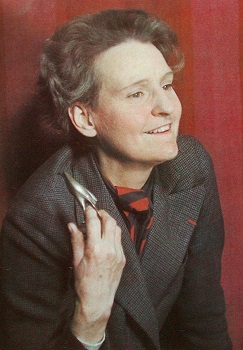

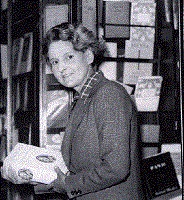

Sylvia Beach - Interviews & Portraits |

|

|

Portraits of James Joyce - An Album |

|

|

| 1: Rationale |

The following remarks seek to resolve some prevalent confusions as to date and setting of several photo-series taken of Joyce and Sylvia Beach together at her Paris bookshop Shakespeare and Company - photos which are commonly used to illustrate books and websites concerned with each of them, though often represented in careless and anachronistic ways as regards the time and location in question. Thus, a photo taken by Gisèle Freund in 1938 might be ascribed to the 1920s while another taken at rue Dupuytren before Beach moved her premises to rue de l’Odeon in May 1921 might be ascribed to the second-named premises. Here I look at all such variations with a view to distinguishing the series from each other as clearly as possible, using both internal and external evidence - i.e., the disposition of shop-fronts and the furniture and the available information on the origin of the photos - while incidentally compiling an album of the photographs in question, all of which are available on internet today.

There exist, in fact, three “Shakespeare and Company” series in which James Joyce and Syvlia Beach appear together. The earliest was taken at her first premises at rue Dupuytren during early 1921; the second at her premises on rue de l’Odéon, to which she moved in May of that year and consisting in a single photo in which the two appear seated a desk under the “Scandal of Ulysses” poster which has rendered it the best-known and most often-printed of all. It is notable that this photo includes a view of the four extant photos of Beach and Joyce (with others) taken by an unknown photographer at rue Duputryen - i.e., the first series mentioned here. The third series taken fully sixteen years later at the later premises by the distinguished German photographer Gisèle Freund who was permitted to follow Joyce around while going about his business in Paris during three days in the summer of 1938. In this series it appears that a conscious attempt was made to imitate the setting of the earlier one of 1922. (A final series taken by Freund in 1939 for Time Magazine captures Joyce on colour film and contains images of Beach taken entirely separately in the same period.)

The difference between each series is more-or-less distinctly marked by alterations in the appearance of the persons portrayed in them - alterations due to time no less than fashion though most clearly reflected in the sartorial array of the persons depicted, including crucially such details as Beach’s collar, Joyce’s bow-tie, and an eye-patch which bears witness to his opthalmological history at the two periods in question. Similarily, changes in the furnishings of Miss Beach’s premises, and particularly her desktop, bear testimony to the move from rue Dupuytren to rue de l’Odéon although the transportation of an identical table from one place to the other creates some latitude for confusion and might even suggest that Miss Beach occasionally reverted to the desk-top arrangement of an earlier period, swapping from a drawing-room arrangement of table ornaments to a more commerciailly-minded array of rubber stamps and papers organised in business-like piles.

The main thrust of my argument is that the photographs of Joyce and Sylvia Beach in Shakespeare and Company in the earliest 1920s which are widely supposed to have been taken at rue de l’Odeon are actually contemporaneous with the two taken of the writer and the bookseller at the doorway of her premises in rue Dupuytren. I arrive at this conclusion primarily by comparing the bookshelves and the layout of the shop-interior and by noting the position of Miss Beach’s desk and its furnishings. Here the chief anomaly consists in the fact that articles of bijou pottery sitting on that table in 1920 pictures strangely recur in the series taken by Gisele Freund in 1938 though not in the most famous shot of all - Joyce and Beach sitting together in rue de l’Odeon in 1922 beside the celebrated “Scandal of Ulysses” poster printed by The Pink ’Un - a deeply conservative British newspaper primarily devoted to racing results and sporting matters. There a desk-tree of lending-library rubber-stamps dominates the scene (as I have already mentioned).

The result, I hope is to give new insight into the mentality of the subjects of the photographs as well as a better idea of the way in which the space at either premises was disposed and organised. Sadly the account given here falls short of completeness because as I have not been able to trace the photographs to their sources in printed works and/or library collections as completely as I would wish. I have, in fact, reached these conclusions through close examination of the pictures available on internet in conjunction with the illustrations in Beach’s own memoir Shakespeare and Company (NY Harcourt, Brace 1959; rep. Bison [Nebraska UP] 1991) a copy of which I picked up at Abebooks.com. The effect of that source was to confirm that the conclusions were accurate - or, at least, to demonstrate that no conclusion about any individual picture is contradicted by the information attached to it in Beach’s book. My excuse for this deficiency is that I currently lack opportunity to make the necessary research trips being posted full-time in Brazil as a university teacher. In that sense, this page must be taken as an exploratory study and a promissory note in the spirit of the Beckettian imperative, “Fail better”.

[ This page is an adjunct to the James Joyce archive in RICORSO - online. ] |

[ top ]

| 2: Setting the Scene |

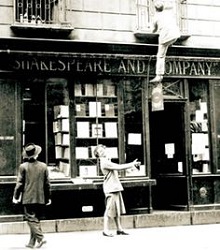

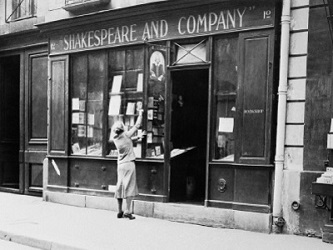

Premises of Shakespeare & Company (Paris) |

|

|

Syvlia Beach in Rue Dupuytren, 1919 |

Beach and others, Rue Dupuytren, 1921 |

|

|

|

|

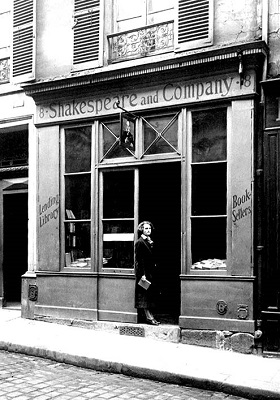

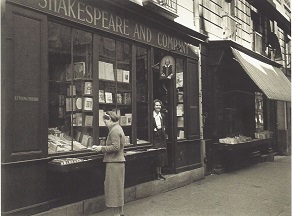

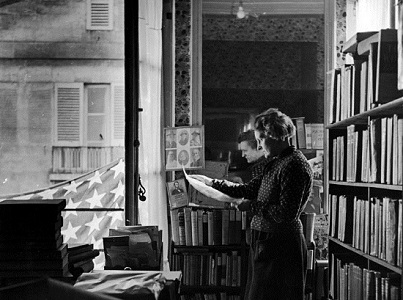

Beach at Shakespeare & Co at 12 rue de l’Odéon

in the 1930s |

|

|

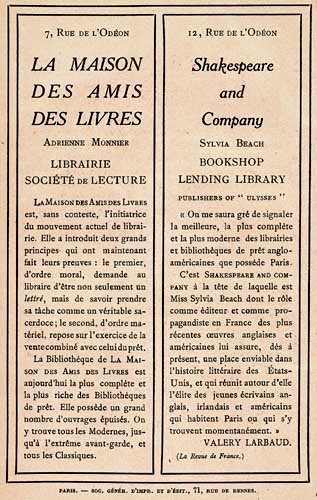

James Joyce first met Sylvia Beach on 11 July 1920 at a party given by André Spire and was afterwards a regular visitor to Shakespeare and Company, the English-language bookshop which she had opened on 19 Nov. 1919. He rightly regarded her shop as the hub of Anglophonic literary activity in Paris just as La Maison des Amis des Livres, the longer-established bookshop of Beach’s friend Adrienne Monnier - whom Joyce also met on that occasion - was a hub of French literary culture in the city.

Beach, the daughter of a Presbyterian minister who had moved his family from Baltimore (USA) to Paris, and Monnier, the daughter of a Parisian postal worker, were lovers and life-long friends up to Monnier's death by suicide in 1955. (They shared a flat further up the rue de l’Odéon in early year while their shops were across the street from each other.) Miss Beach died in 1962, a revered remnant of the literary scene in inter-war Paris. It was in Monnier’s company that Beach met Joyce and with the support of these two that he gained the support of the French man-of-letters Valéry Larbaud for Ulysses on the eve of its publication by Beach in 1922. Larbaud was a leading light at Nouvelles Revue Française, by far the most celebrated literary journal of the age - and so-regarded by many in England, as Arnold Bennett bore witness in his piece on Joyce of which we will hear more later on.

In May 1921 Miss Beach moved her shop from 8 rue Dupuytren to 12 rue de l’Odéon just around the corner from her former premises and diagonally across the street from Monnier’s ‘société de lecture’ [reading club] - as La Maison des Amis des Livres was styled on an explanatory panel prominently displayed on the facade of her shop at 7 rue de l’Odéon. It was at her earlier premises that Beach undertook to publish Ulysses on 25 March 1921 and at the later one that she actually fulfilled that promise a little less than one year after with its rush appearance on 2 February 1922.

All of these addresses are in the VIième Arrondisement on the Rive Gauche in Paris, beween Latin Quarter and Saint-Germain-des-Près with the Sorbonne and the Boulevard St. Michel at a right angle - a cultural-charged area of the city well-known to Joyce from those youthful trips to Paris during 1902-03 which he so brilliantly memorialised in the “Proteus” episode of Ulysses. And when he returned to the French capital in 1920 - having passed much of the interim in Trieste - he resumed his familiarity with that neighbourhood and rarely lived outside it in spite of changing his apartment twenty times in the ensuing 19 years. [ See a list of Joyce’s Paris homes - as attached.] |

|

| 3: The Photographs |

The best-known photograph of Joyce and Beach together is certainly the one in which he sits with her at her work-desk in the new premises in their characters as author and publisher of Ulysses in 1922 [see above]. In it a pair of advertisements for The Sporting Times and The Bookman can be clearly seen on the wall behind the sitters. It is these posters which supply the best clue to the actual date of the photograph which was plainly taken at the end of 1922 when the first reviews of Ulysses were already in.

Topping the bill in The Sporting Times, according to the text of the poster, is an alarmist article entitled “The Scandal of Ulysses” in which a pseudonymous (and unknown) reviewer called “Aramis” forewarns his readers that Joyce’s new novel would ‘make a Hottentot sick’ - an imperialist turn of phrase which serves to identify both author and audience as members of the English middle class embroiled in the Great Game - as Rudyard Kipling called the business of maintaining the British Empire against all comers in his novel Kim (1901). Irishmen and Hottentots, the review implies, are closey allied in spite of their disparate racial histories and their mutual geographical remoteness from each other. Neither of them are gentlemen.

Ironically the same poster offers odds of 7 to 2 for a race-horse called Killeen who can safely be assumed to be an Irish nag given that Killeen is the name of an Irish country-house in Co. Meath long-associated with the family of Lord Dunsany, an aristocratic writer very much at the other end of the social scale of Irish literary production from Joyce himself. The bookies’ odds are given here since the paper in question - commonly called “the Pink Un” - was the Sporting Times a journal with a conservative readership which became widely known for its support of the landed interest and the general maintenance of Victorian values in post-Victorian England.

In ‘Concerning James Joyce’, a review of Ulysses for the August issue of The Bookman which is the subject of the second poster - the distinguished English novelist Arnold Bennett begins by making it clear that he considers Joyce’s Irish Catholic longueurs in A Portrait of the Artist distinctly over-egged before subjecting the new novel to unqualified dispraise. Later on, in a piece on Anna Livia Plurabelle for the Evening Standard written in 1929, he would chivalrously refer to Joyce as a literary genius, if one who had ‘lost his way’. (He was not alone in this outlook and Patrick Kavanagh was later to echo the idea the phrase in an article on Joyce in diary-form for the James Joyce special issue of Envoy in April 1950. For him, Joyce’s last work Finnegans Wake (1939) was ‘the delirium of a genius who had lost his way.’ Whether this constitutes plagiarism or cliché I leave it for Kavanagh scholars to say.

It seems impossible to identify the photographer responsible for the “Ulysses” photograph of 1922 [as above]. Neither did it appear in Richard Ellmann’s life of Joyce nor - unsurprisingly - in Bruce Arnold’s The Scandal Ulysses (1991) which takes its title from the headline on that very poster but is exclusively concerned with copyright shenanigans and critical vagaries surrounding the publication of the “corrected” Ulysses (ed. Walter Hans Gebler, 1984.) As regards the date, the photograph can loosely be to autumn of 1922 in view of both the respective dates of publication of the notices in the Sporting Times and Bookman advertised in the posters. This fits in well, also, with what is known about Joyce’s medical history in regard to the eye-patch he is wearing in the photo. [For more about Joyce’s eye operations, see below.]

§

It happens that very different set of photographs of Joyce and Beach together was taken at the same premises by the celebrated German-French photographer Gisèle Freund in the summer of 1938 -fully sixteen years after the first [see below]. Having gained access to his good grace by using her married name Bloom as an introduction, Freund was permitted to follow Joyce around for three days, taking pictures indoors, then with his family in the garden of the ground-floor apartment, then afterwards in the street presumably en route to Shakespeare & Company and finally inside Sylvia Beach’s shop at 12 rue de l’Odéon.

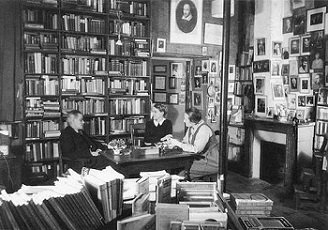

In this series we see the same desk and bookshelves as those captured in the “Scandal of Ulysses” shot - though with rather different desk furnishing from the workmanlike rack of rubber stamps in the 1922 photograph. In neither of these does the porcelain China box appear which forms the chief ornament on the same table in a still earlier set of photos dating from 1921 and probably set in rue Dupuytren - though commonly cited as having been taken at Shakespeare and Company in rue de l’Odéon. (It is the actual location of this last-mentioned set which forms the point of enquiry of this article.) On the other hand, there is a floral arrangement on the table in the 1938 pictures which as not been seen since the shots of 1921, having been cleared from the table by the urgent business of publishing Ulysses - the achievement commemorated in the photograph of 1922.

One of the incidental benefits of Freund’s 1938 shoot is that we get a much better view of the interior of the bookshop than in the earlier ones both on account of the wider-angle lens and because the component photos in the series are taken first from one side of the room and then the other. Thus we know, for instance, that the premises at rue de l’Odéon contained an ornate fireplace not seen in the 1922 photograph taken in the same room (though visible on one other extant photo). There is another difference: In addition to the main actors a third person is also present. This is Adrienne Monnier by far the most dynamic member of the group both as regards mobility and manual gestures. It can only be supposed that her animation was due to her rôle as master of ceremonies and de facto director, having arranged the collaboration between Joyce and Freund in the first place.

An obvious difference between the earlier and later photos is the apparent age of the sitters. Yet, although Miss Beach is clearly distinguished from her earlier self by an altered hair-style as much as her general appearance, she has chosen to wear a similar white collar over a dark dress to the one worn in the session of sixteen years earlier. Indeed, that appears to have been her stock regalia during the 1920s - perhaps in emulation of her American Puritan forebears. (She regarded her services to modern literature a fitting ‘mission’ for a preacher’s daughter.) By 1938, however, she was generally wearing brown and grey suits, to judge from the black-and-white photos taken at the exterior of the shop in which she appears. One of these, at least, is dated 1939 and identified with Gisèle Freud [see below]. In the colour shot taken by Freud one year later in 1939 she is wearing a fine pepper-and-salt woollen jacket with a black and red silk scarf worn cravat-style while the distincive red thread of the legion d"honneur shows on her label [see below].

All of this suggests that her outfit in the 1938 shoot is a conscious allusion to the earlier meeting in 1922. Likewise Joyce is wearing a bow-tie which, if not the identical article of clothing, harks back to his regalia in earlier picture. Indeed, at one point he rather self-consciously touches the bow as if to draw attention to it and, though that may be a critical inference too far, the suggestion is hard to avoid that the main actors were determined to reproduce the atmosphere of the earlier session sixteen years before. By contrast, in the contemporaneous portraits taken at his home by Freund he is wearing a plaid neck-tie. In comparison the bow-tie is something of a return to the earlier day in 1922 when Joyce triumphed with Ulysses. And now he is about to hit the news again since Freund is working for Life and will return in 1939 to take the cover-picture for Time Magazine.

|

|

|

|

|

Joyce with Syvlia Beach & Adrienne Monnier

at Shakespeare & Company in 1938.

|

|

Photographs by Gisele Freund.

|

The

archive of Freund's book James Joyce in Paris: His Final Years (Harcourt Brace & World 1965) was acquired by the University of Victoria Libraries from her estate in the early 1970s. Some 161 photos of Joyce and others including including W. H. Auden, T. S. Eliot, Henry Miller and Virginia Woolf are contained in the collection together with the correspondence, manuscripts, paste-ups and proofs connected with the book itself. See Vitoria UL - online; accessed 29.09.2017. [Note: The image at the bottom left (above) is often horizontally flipped ] |

|

§

Besides the “Ulysses” shot of 1922 and the Gisèle Freund’s photo-essay of 1938, there exist two further series of images associated with Shakespeare & Company of which one at least is known to have been taken at her early premises on rue Duputyren during 1921. The most famous of these is a brace of photographs taken at the doorway - one from inside and one from outside the shop - in which Joyce has the dandified air imparted by a bow-tie, a fedora hat with white or semi-tone shoes while Miss Beach, also sporting a bow with otherwise rather marmish clothes, is apparently a blonde for the season.

Exterior and interiors of the doorway at rue Dupuytren. In the Buffalo Library Catalogue - where they are held - the first is said to have been taken by an unknown photographer in 1920 and the second in 1921 according to a note on the verso by Samuel Beckett [SB] to the effect that the publication de Ulysses was already en train.

That these two images were captured at the Miss Beach’s shop in rue Dupuytren can easily be established with reference to the glazing bars above the shop-front door along with other details which rendered that premises quite unlike the frontage at rue de l’Odéon. In attire, the figures in both images of these are identical at all points - excepting perhaps Miss Beach's blonde hair, which may be an effect of the light. that they are taken by separate hands on separate occasions - as Beckett seems to testify - is almost certain. At least, to suppose a single ‘sitting’ would be to contradict his evidence.

A boy looking down from the balcony above the door suggests an unlooked for ‘epiphany’ to which, unfortunately, we cannot add a personal name. Perhaps for that reasons it is all the harder overlook his claims to serve as the subject of a novella set in interwar Paris. [Ill., Joyce and Beach in 1920 and 1921.] |

|

|

There exists another series of Joyce-Beach photos set at Shakespeare and Company and which is usually identified with rue de l’Odéon though this appears to be a pure assumption - and an erroneous one, at that. This series includes John Rodker and a young woman who is known to have been Miss Beach’s sister Cyprian, then visiting Paris [as below]. Here the view of Joyce, Beach and Rodker standing in conversation reveals a very low shelf-profile, compared with other photos of the interior of Shakespeare and Company in which the figures are seen sitting in front of bookshelves that fill the entire height of the wall behind. This difference in itself serves to distinguish the earlier premises from the later and strongly argues that the photo which includes John Rodker and Cyprian Beach were taken inside the shop at rue Dupuytren and not at rue de l’Odéon.

In the standing photograph, moreover, Miss Beach stands at a desk identical to the one which appears in the 1922 “Scandal of Ulysses” photo and which reappears in the series known to have been taken by Gisèle Freund at Rue de l’Odéon in 1938. Oddly, the desk furnishings are strikingly different in the 1921 and 1922 shots but seem to return to the 1921 arrangement for the photos taken by Freund 1938. It is impossible, however, to assign the early pictures to the same occasion as the 1938 series if only because the age and attire of the persons pictured in them are so manifestly different. The identity of the table in all these series can be confirmed by comparing the turned legs and the fluted edge of the table-top in each. This is actually a constant in all of the pictures identified with Shakespeare & Company whether in 1921, 1922 or 1938 and it is difficult to resist the conclusion that it was transported from rue Dupuytren to rue de l’Odéon at the time of the move of premises in circa May of 1921.

§

Let us now consider if the series of pictures in which John Rodker appears might be solidly identified with rue Dupuytren rather than rue de l’Odéon. It appears, in fact, that the Joyce who appears in the exterior shots unquestionably taken there is wearing identical clothes to the one seen in the interior shot which includes Rodker - together with the reading woman who is known to have been Cyprian Beach. Now, this shot is usually assigned to the newer premises at rue de l’Odéon though we have already noted a lower book-case than that extant in 1922. One might also feel that the position of the desk and door fail to correspond to the series of 1938.

|

Joyce, Beach and John Rodker and

Cyprian Beach (acc. Sylvia in

Shakespeare and Company, 1959.) |

|

Orig. at Buffalo Univ. Library - online.

|

|

It is hard to affirm that Sylvia Beach is wearing different clothing in the exterior shot and in the interior shot under discussion. Joyce, on the other hand, might have done no more than taken off her hat. It is highly plausible, however, that he wore very much the same regalia on the occasion of all his visits to Shakespeare and Company at whichever premises. Beach's seemingly blonde hair in one and bleached hair in the other constitutes an obstacle to identifying them with the same occasion - but this can well he attribute to an effect of photography exposure especially given the wider aperture required to shot from inside the room without losing details of the persons standing in the doorway, as in the photo in question.

A final clue to the location of the interior shot is the presence of John Rodker in the background. Rodker, whom Joyce met during 1920, offered to bring out the 2nd edition of Ulysses using his own printing press. In the event it was to be brought out by Egoist Press in London after the Shakespeare & Company first edition was exhausted, using the same plates of the other. Ironically, a detail from this very photograph cropped to exclude all but a hint of Joyce’s shoulder has been adopted by Alex Rodker in compiling the Rodker family page at MyHeritage in very recent times. No information is supplied there as to the date or the occasion [see online] - but fortunately it isn't needed since the identity of the female figure on the right is given as Cyprian in the relevant caption in Beach's autobiography where it first appeared, and where the context makes it clear that the date in question fell before the move of premises to rue de L’Odéon.

It’s worth pointing out that - as with many other photos associated with Shakespeare and Company at any venue - the focal range of these interior shots reveals the use of flashlight in accordance with the basic principles of photography since low light calls for wider aperatures and consequently sacrifices depth of field. (‘Circles of confusion’ is the technical term used for out-of-focus spots arising from such wider aperatures - a term that might be fittingly applied to Finnegans Wake.)

Next, we might consider the three photographs taken outside the premises at rue Duputryen which are all held in the Buffalo Collection. Firstly, there is one of Sylvia Beach solo - presumably as the newly-installed proprietor of the store since the date is given as 1919. although Beach attached no date-line to it in Shakespeare and Company (1959) where the picture serves as the first of 39 illustrations of her autobiographical account (on p.108-facing). Secondly, there is a shot of Beach with a man-and-woman couple known to be Carla Bodon and Stephen Vincent Benét who visited Beach at her premised on rue Dupuytren in 1921. The third is, of course, the well-known shot of Joyce and Beach facing each other in the doorway as seen from the front with a young boy on the balcony above the shop-door, presumably an purely fortuitous actor in the scene.

Can this have been taken on the same occasion as the interior shots in which he is seen in company with Beach, Rodker, and Beach’s sister? Or is it perhaps a companion-piece to the outward-tending photography which Beckett has identified with the aftermath of the contract between Beach and Joyce for the first edition? In visual terms, at least, it seems more compatible with the Rodker shot - as I call it for short - and less with the outside shot featuring the happenstance boy. Equally, it may pertain to neither of these occasions and simple be another shot at another time between their first meeting at a party given by Andr’e Spire on 11 July 1920.

Aside from the evidence of Beckett's later hand-note on the verso dating it to 1921 when the publication of Ulysses was already ‘en train’, there is little to go on. Aside from biographical facts and questions of attire, which seem to offer little help, there is the physical appearance of the shop front and particularly the windows in one shot and another. It is noticeable, for instance, that in the Bodon-Benet shot there is a white bar across the left leaf of the shop door which also appears in the earlier picture of Beach in her newly-opened shop - the charmingly named Shakespeare and Company which she founded at 8 rue Duputryen in Nov. 1919. A slightly wider band appears in the left-hand side of the doorway in the interior shot of Joyce and Beach - though actually the right side when viewed from the exterior. This appears to be a door-sign or else a momentary advertisement, and the difference in scale (it is twice as deep) implies that it cannot be the same occasion as further incidental clues tend to confirm.

In the well-known exterior shot of Joyce and Beach Joyce is standing against the left leaf of the door and it is difficult to judge whether the door-sign is in place or not. Yet window display at either side of the door is not the same as in the other photograph - indeed, the arrangement is different in all three shots of Beach outside her shop with or without other people in the frame. Finally, the well-loved and oft-reprinted shot of Joyce and Beach outside her shop in 1921 contains a delightful anomaly in that a young boy perched on the narrow first-storey balcony above the shop-door has been fixed for eternity in the famous frame. Could this be Georgio? Hardly: in 1921 Joyce’s son is 16 years of age. No, it must be the son of the family dwelling upstairs since there is no evidence that Syvlia Beach herself had tenancy of the rooms above the shop. Indeed, if only for that reason, the move to rue de l’Odeon was well-advised.

In summary, there is no evidence that the shot of Joyce and Beach at the doorway of rue Dupuytren and taken from the interior is synchronous with the shot of Joyce, Beach, Rodker and Cyprian Beach inside the bookshop. Nor is there any reason to believe that the shot of Joyce outside the shop with Beach where a young boy appears in frame is synchronous with either either. But the photograph of Joyce and Beech taken from the inside identified by Samuel Beckett while working as Joyce's amanuensis is therefore taken to be a shot of 1921 after the signing of the Ulysses contract and prior to publication. Who the photographer in each of these cases, we simply do not know though it may be supposed to be a co-worker or a friend or simply a different photographer on each occasion. What is clear is that there seemed to be only one angle from which the shop could be effectively photographed and that is slightly downhill and at an angle of about 45 degrees.

|

The forensic interest of all such details mentioned here is obvious enough yet such differences remain indecipherable or, at least, contradictory in their implications. The happiest conclusion might be to suppose that the interior shot and the other with a boy on the balcony were taken on the same day - and even perhaps that the boy came to the winow to see what all the fuss was about just in time to be included in the shot of author and publisher outside the famous shop. Otherwise it is simply another occasion. When did all of this transpire? It was on 10 April 1921 that Miss Beach signed a contract to publish James Joyce's great novel Ulysses and the photo midentied by Beckett must have occurred between that date and May 1921 when she departed for rue de l'Odeon. The Rodker shot cannot be dated to the period after publication of the novel when he was in contention to publish the second edition since by then Sylvia Beach had moved to her later location - unless we consider the setting of that shot to be the interior of Shakespeare and Company in early days at rue de L'Odeon. If so, the shelving and lay-out have altered mightily by February 1922 when the New York Times took the famous "Scandal of Ulysses" shot which includes, among its props, the very picture in question which is commonly identified with rue Dupuytren.

Who is the woman on the right? |

|

—Nöel Riley Fitch, The Lost Generation (1985), p.69.

[See letter to Holly, 23 April 1921 - below.]

|

Note: It is probable that Fitch has mistakenly identified Holly as the second female figure in the photo since the actual print held in Buffalo University (NY) identifies that person as Cyprian Beach. |

|

§

In addition to the Rodker photo, there exist two others in the same series commonly shown on websites where they are often represented as images from the 1920s without any regard to actual chronology. Often, again, separate images of Miss Beach and Joyce are cropped from the same photograph - originally printed in Beach’s Shakespeare and Company (1956). The separate versions - oft-seen on internet - and the unified original can both be seen in the illustration below where the background shelves, table edge, and even some objects on it merge perfectly if the images are set side by side. (The original can be inspected at the University of Buffalo Libraries Digital Collections - online.) In it, Miss Beach is seen to look in Joyce’s direction and he in hers, while a single sheet, or pile of sheets, lying on the table is actually split by the borders of the respective pictures in the most widely circulated versions.

Everything serves to suggest that the standing group and the seated figures belong to the same moment. Yet, while the table in both of these is clearly the self-same that features in the 1922 “Scandal of Ulysses” shot - as also in the 1938 series taken by Gisèle Freund - the room in which the encounter is staged is just as certainly not the one in the 1922 image or the 1938 series. The implication is plain: these pictures were taken at rue Dupuytren before the move to new premises on rue de l’Odéon in May 1921 - a date agreed by all commentators though Richard Ellmann in his biography of Joyce simply says ‘some time before autumn 1921’.

It happens that the seated figures appear to be positioned before a backdrop of bookshelves which might well rise to the cornice or the ceiling - an arrangement adopted at the second premises as can be seen from so many photos of the interior at rue de l’Odeon [or which see above]. Yet a quick glance at the image showing the subjects of the series standing in the room with John Rodker in the background immediately reveals the fact that the illusion of high book-shelves is created solely by the camera-angle in the seated shot. In fact the shelving at rue Dupuytren - a ‘cubby-hole’ in one account - stopped at shoulder-level, unlike the full-height shelving in the premises of Shakespeare and Company on rue de l’Odéon behind its significantly wider frontage.

As regards the venue of the sepia series, the proof is perhaps to be found in a photograph of Miss Beach taken by the ‘surrealist sisters’ Lucie Schwob and Suzanne Malherbe (otherwise Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore) at 8 rue Dupuytren in 1919, as the inscription clearly states. Here the room contains low-profile shelving identical with that in the Rodker image and, by extrapolation, consistent with the shelving in the kindred photograph of Beach and Joyce seated together at her ubiquitous desk. That the shop at rue de l’Odéon was, by contrast, furnished with high shelves is apparent from almost every image of its interior including, notably, the “Scandal of Ulysses” shot of 1922. It is perhaps admissible to guess that the accumulation of stock with advancing time rendered the lower profile increasingly unviable, especially since the shelving at Shakespeare and Company was at all times affixed to the walls. Nor did Sylvia Beach create the cluttered book-cave installed by George Whitman in the latter-day Shakespeare and Company, established at 37 rue de la Bûchrie for the benefit of devotées of the “lost generation” and other Anglophone tourists in Paris at large.)

Additionally, it is known that Miss Beach lived above the shop at rue de l’Odéon while the little boy appearing on the balcony in the doorway shot with of Beach and Joyce in 1921 which is undeniably set at rue Dupuytren strongly suggests that she lived elsewhere during her sojourn there - perhaps a sufficient reasons for changing address. There is, in fact, an interior door in the Rodker shot and this might lead to a stairway but the corner position of that door suggests a back room or rooms rather than a flight of stairs. (Parisians and Parisiennes - some architectural fine-tuning might be called for here!)

This seems, indeed, to have been the definite feature of the original conception behind Shakespeare and Company: the use of low shelves, as can be seen in the portrait of Miss Beach [on the left] taken shortly after she opened her shop at rue Dupuytren. Indeed, several of those who frequented Shakespeare and Company in either of these adjacent streets thought it essential to the distinctive appeal of the shop that the owner had arranged the shelves which held her stock-in-trade in living-room style along the ‘perimeter’ walls, rather than using the obtrusive shelving that occupies the central floor-space in any other bookstore. In addition, a floor covered with the Eastern rugs which he brought back from wartime days with the Red Cross days in Serbia served to sustain the atmosphere of a literary household rather than a place of commercial business.

[ See gallery of images of Sylvia Beach - infra. ] |

§

A better guide to the chronology of the photos in the series under consideration is perhaps Joyce’s attire, which seems identical that worn in the shots taken in the Dupuytren doorway. There is a small difficulty in that Beach’s seems blond in both of the Dupuytren doorway pictures, whether shot from the inside or the outside, and this argues to the contrary - i.e., that the date of the photographs are sufficiently remote from one another to permit a visit to the hair-dresser in the interim. But it is not, in fact, believable that Sylvia Beach bleached her hair or invited anyone else to do it and the apparent blondeness must be ascribed to photographic variations [as attached]. Yet, taking her the colour of her hair as the main indicator of the chronology of the photos, it must be admitted that the interior shots could well have been taken in either premises either before or after the door-way shots, on the unlikely supposition that she changed her colour either before or after the latter.

While the facts considered so far more than tenuously suggest that several photographs conventionally attributed to rue de l’Odéon as their setting were actually taken in the earlier premises at rue Dupuytren, it must be admitted that there subsists a possibility that they were taken at rue de l’Odéon in very early days. If so, then the agreement to published Ulysses has already been arrived at (as it was on 11 April 1921); if not, it is likely that these pictures were taken to mark the spirit of that undertaking. Certainly they do not exude the air of post-publication triumph which is so much a part of the atmosphere in the ensuing series of photographs taken at Shakespeare and Company in February 1922.

We know perfectly well that the “Scandal of Ulysses” photo was taken in autumn 1922 from the evidence of the posters included in the setting. Yet another sort of evidence which could be brought to bear on the question of its date pertains to Joyce’s medical history at the period in question. In May 1922 he suffered an acute attack of iritis, and in April 1923 he underwent sphincterectomy on his left eye - only weeks after the extraction of his teeth (respectively in Paris and in Nice). The teeth were replaced by dentures in June 1923. While Joyce wore an eye-patch at various points in his life - sometimes on the left eye, sometimes on the right - he was certainly doing so in the autumn of 1922, which would fit well with the aftermath of the publication of Ulysses suggested by the posters on the wall.

[Closer consideration will be given to Joyce’s ‘eye-patch’ period when it comes to dating the first series of photographs by Berenice Abbott later on - as infra.]

The evidence for this lies in his letters. In November 1922 he had a falling-out with Beach arising from his urgent wish for a third imprint of Ulysses - a wish that sparked her indignation since she had already put herself at risk of seeming to connive in a ‘bogus’ first edition by issuing a near-identical run of 2,000 copies on 17 October which sold out in a month. Nor was she prepared to ‘boom’ the book by soliciting reviews from all the writers in her acquaintance as Joyce insisted that she should. (Beach knew well that the pleasure and pain of publishing Ulysses was hers while the profit was reserved for Joyce.)

The quarrel, which was soon made up, held forebodings of others to follow - culminating with Joyce’s insistence that she relinquish her world rights in Ulysses in December 1930 to facilitate its American publication. Nor was Joyce entirely unapologetic. In giving an account of the first fracas to his patron Harriet Weaver, Joyce wrote:

Possibly the fault is partly mine. I, my eye, my needs and my troublesome book are always there. There is no feast or celebration or meeting of shareholders but at the fatal hour I appear at the door in dubious habiliments, with impedimenta of baggage, a mute expectant family, a patch over one eye howling dismally for aid. (Letter of 17 Nov. 1922; Letters, Vol. 1, p.194; my italics.)

Besides the eye-patch, we might also consider the bow-tie which he sports in the picture. In March 1922 Robert McAlmon and his wife, living then in Nice, invited the Joyces for a holiday in the Côte d’Azur. Finding himself unable to travel due to last-minute problems with the printer Darantière and the cover of Ulysses, Joyce asked McAlmon to give him a neck-tie by way of consolation. By ‘neck-tie’ he probably meant the modern kind worn by McAlmon and other young Americans rather than the bow-ties he himself had favoured throughout his Triestino, Züricher and early Paris days - and which he wore less frequently (and finally not at all) in later photographs.

Apparently Joyce assumed that his expatriate friend travelled with ties galore, as he explained in a letter of thanks. In fact McAlmon made a shopping trip to Cannes especially to buy a number of expensive ties for Joyce, together with a handsome ring - presumably to take the errand-boy look off the gift. When Joyce received the parcel he wrote a letter which reveals that he had intended to scrounge the neck-tie rather than to compel its purchase. In a postscript to his rather elaborate explanation, he gratefully described the ring as ‘very nice and episcopal’, suggesting approval and amusement.

Recounting the episode, Joyce’s biographer adds in a footnote that the writer ‘formed a large collection of ties in Paris, and came to pay an almost dandiacal attention to his clothes.’ [Richard Ellmann, James Joyce, rev. edn. 1982, p.532, n.] By way of illustration one might cite the occasion in May 1924 when he was sitting for a portrait by the Irish painter Patrick Tuohy - renowned like John Butler Yeats for perfectionism - excused his delay by saying that he was trying to capture his subject’s soul, causing Joyce to answer, ‘Never mind about my soul, be sure you have my tie right.’ (Ellmann, op. cit., 565-66.)

|

| |

[ top ]

| 4: The Photographers |

|

In 1921 Berenice Abbott, a friend of Djuna Barnes and Kenneth Burke, arrived in Paris from Greenwich Village (and before that Springfield, Ohio). In 1923 she began working for Man Ray as a darkroom assistant and ‘took to photography like a duck to water’ - with the result that she was able to hold a one-man show in 1926. After that she spent a year studying in Germany before setting up a studio on rue Servandoni - though briefly she had had one before departure on rue de Bac. In 1929 she returned to New York where her greatest work was done (viz., Changing New York, 1935) and where, like Beach and Monnier, she lived with a woman, Elizabeth McCausland in a life-long partnership. [See Wikipedia > Berenice Abbott - online.]

Her studio portrait of Joyce dating from 1928 [on the right] shows him serious (even doleful) but relaxed, wearing a neck-tie with rings, fedora hat and cane while sitting on a wooden chair - possibly a dining-room ‘carver’ or else a studio chair to the same pattern. I call it a studio portrait because the backdrop is obviously the kind of canvas screen with a daub of muzzy colour used by photographers to abolish background noise and to enhance the focus on the subject - an effect which can only otherwise be arrived at by setting a wide aperature to create shallow depth of field and therefore what they call ‘circles of confusion’ outside the exact point of focus.

In other words, both the setting and style (or, more exactly, the technique) are widely different - as is the sitter himself in several important respects. It could be said, by way of short-hand, that the first three shots above are still Man Ray-ish - allowing that the first is obviously a cropped blow-up. As to Joyce’s attire, he is known to have donned a white jacket while composing, and the pictures in the ‘white-coated’ series therefore bear the aspect of writer-at-work in spite of his elegant shirt and rather showy bow-tie. (It is worth mentioning here that there are other members of each of the two photographic series on question.)

Not technique nor sartorial array, however, but relative age is the most obvious pointer to the different period in which the first three and the fourth shots shown here were taken. More or less self-evidently, the Joyce of the first three is younger than the Joyce of the fourth which we know to have been taken in 1928 from Abbott’s own testimony - that is, after she returned from Germany and before she went back to America. To state matters in the simplest way, Joyce’s moustache is whiter in the studio portrait of 1928. It is therefore likely that the first three were taken before her departure to Germany in 1926, but not before 1923 when she first picked up a camera.

If the photographs were known to have been included in her exhibition of 1926 we could narrow down the dates even further - placing them between 1923 or 1924 and 1926. In any event, it is quite impossible that her ‘white-coated’ series was taken in 1922 on biographical evidence relating to Berenice Abbott, and cannot therefore be strictly contemporaneous with the “Scandal of Ulysses” picture unless the latter was actually taken later than the publication year of Ulysses. This has multiple implications. Either Joyce sat for Abbott at another moment when he was wearing an eye-patch on his left eye and sporting a spotted bow-tie (perhaps the very same one), or else the “Scandal of Ulysses” was taken later than we think - perhaps in 1924 or even as late as 1926.

There are, in fact, three pieces of visual evidence to be considered when assessing the temporal proximity of the Abbott picture and the Joyce-Beach picture with which we started. The first is Joyce’s general appearance in point of age and grooming. Here it might be said that the hair is closer cut around the ears and a little greyer also, while the chin-beard is a little fuller in the Abbott pictures than in the Joyce-Beach photograph. There is also the matter of hair-oil in the picture taken in Shakespeare and Company. The sitter in the Abbott pictures seems to be (momentarily) liberated from this necessity - the ruin of upholstery and the raison d’être for the anti-macassar. Yet, although the pictures were certainly not taken on the same day, or perhaps even the same year, they cannot be very far apart. A year or two might be the furthest extent of the lapse of time between them.

A second order of evidence may be considered in attempting to date exactly the photographic session in which Berenice Abbott captured Joyce garbed in a ‘white-coated’ and equipt with an eye-patch which he obligingly took off for some of the shots. The following synopsis of his ophthalmological history will serve to set the scene:

Medical history: The eye operations of James Joyce |

1917: Joyce suffers attacks of glaucoma and synechia, 18 Aug.; Ernst Siedler performs iridectomy on his right eye, at Augenklinik, 24 Aug.

1918: recurrent eye-trouble in Oct. and Nov.;

1922: suffers acute iritis, May 1922; suffers conjunctivitis and threatened with immobility of fluid leading to glaucoma and blindness, London, Aug. 1922;

left eye drained with leeches by Dr. Louis Colin, Nice, Oct.; Dr. Borsch recommends sphincterectomy following removal of teeth, Oct.;

1923: sphincterectomy performed by Borsch on JAJ’s left eye in stages, 3, 15 & 28 April 1923;

1924: Borsch observes secretion in conjunctiva of JAJ’s left eye, calls for rest, April; JAJ undergoes iridectomy, being the second to the left eye and his fifth eye operation, 10 June 1924;

’s left eye for secondary cataract, 29 Nov.;

1925: tooth-fragment removed, April; a seventh eye-operation performed, April 1925;

1926: undergoes his eighth eye operation, on left eye, June; Dr. Vogt finds caratact in right eye completely calcified and the retina atrophied but defers operation for two years;

1930: ninth operation performed by Dr. Vogt (Zurich), 15 May, and further operations on 3 June and in Sept. 1930, resulting in improved vision;

...

|

Extracted from James Joyce / Life [Files 3/3] - in RICORSO [ online] |

Within this tale of often acute suffering and equal if not greater artistic frustration, it is possible to identify a number of periods when not only eye-patches but also depression must have been the staple of Joyce’s existence - as in the picture on the right. (This was two years antecedent to the manifestation of impending in his daughter Lucia when she threw a chair at her mother and was removed by taxi to maison de santé by her brother on Joyce’s birthday in 1932.)

It is a reasonable inference that the eye-patch in the Joyce-Beach photograph which includes a poster for The Sporting Times for 1 April 1922 is associated with the iritis attack of May 1922 which resulted in the performance of a sphincterectomy on his left eye in April 1923. Allowing for the fact that Joyce experienced an attack of iritis in May of 1922 but travelled to the South of France in October 1922, receiving medical relief from a further attack by leech treatment before returning to Paris in some disarray on 12 November, only to be faced with the prospect of an operation which was eventually conducted in April 1923 - and this only after the extraction of all his teeth, it seems likely that the window of opportunity for the “Scandal of Ulysses” photograph was in November 1922.

|

Normandy 1925 |

|

But that was not by any means a blithe period in the history of relations between Joyce and Syvlia Beach, as we have seen. In fact, he had engaged with her in quarrel over the reprinting of Ulysses to meet what he felt to be a market demand and which seemed to her both a breach of faith in regard to the unicity of the first edition and also a trespass on the arrangement already in place with Harriet Shaw Weaver for a new edition from the Egoist Press in London, using the Darantière sheets. To say that the atmosphere around the table in the “Scandal of Ulysses” photograph was somewhat frosty may, therefore, be an understatement. The later sale of the Stephen Hero manuscript by her into American captivity in 1938 simply came as an aggrevation to relations which were prone to deterioration from the outset - especially as regards the rights to Ulysses which Beach was loathe to pass to the Little Review when it came to printing the second edition.

On the basis of the same kind of inference from his medical history, it is also likely that the left eye-patch which appears in Abbott’s ‘white-jacket’ photos relates to the period of conjunctivitis and consequent spell of rest in 1924.

What finally emerges, then, is a sequence of photographs as follows:

1. Joyce and Sylvia Beach standing together in the doorway of Shakespeare & Company at

8 rue Dupuytren between in early- or mid-1921 [A].

2. Joyce and Beach sitting together in the interior of her shop at rue Dupuytren towards the end of 1921. [B]

3. Joyce and Beach sitting at her desk in rue de l’Odéon between August and September 1922. [C]

4. Joyce as photographed by Berenice Abbott during 1924 - and later in 1928 after her sojourn in Germany. [D]

5. Joyce as photographed with Sylvia Beach and several others, including family members, in late 1938 [E] - this last purposely reproducing the mis en scène of the earlier Shakespeare & Co. shots with Beach in 1922 [C].

[Ed. note: reduced images of each to be added here.]

|

|

[ top ]

Gisèle Freund (1908-2000) |

| |

[ See the Shakespeare and Company photographs of 1938 - supra. ] |

| |

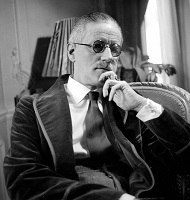

Gisèle Freund’s photos of Joyce date from a three-day photo-shoot in 1938 and another in 1939 [see details - infra]. On the first occasion, the photograph used black-and-white film, on the second colour. In keeping with the photographer’s commission, one of the second kind - which are all closely cropped - figured on the cover of the Time Magazine when Finnegans Wake was published. The earlier b&w images fall into two groups, domestic and public. In a number of the domestic shots, Joyce is wearing a wine-coloured dressing-gown or house-coat, with a shirt and striped necktie and sometimes a cardigan too. In others he is wearing the same striped tie with the same cardigan and a suit - these predominantly taken in the garden, in company with his son Giorgio and his wife Helen and their son Stephen (Joyce’s grandson). Any attempt to set the 1938 pictures in chronological order on the basis of the sitter’s attire must be conjectural but it does appear that the garden shots follow from the dressing-gown shots with only a change of jacket. In the photographs of Joyce with Sylvia Beach taken at this time, by contrast, he is wearing a bow-tie very like - though not actually identical (as close inspection reveals) to the one which he had worn in the 1922 “Scandal of Ulysses” photo taken by Freund at the same venue - that is, Shakespeare & Co. on rue de l’Odéon. This seems to have been a matter of consciously chosen attire to match the earlier occasion, if not a simple preference for ties at home and bow-ties in public places.

There follows here a selection of Freund’s pictures excepting only those taken at Shakespeare & Company, which are given separately - as supra.

|

Photographs of Joyce by Gisèle Freund (1938) |

|

|

|

Four generations |

Joyce with Philippe Soupault |

Enter the cardigan |

|

|

|

Joyce with Helen, Giorgio & Stephen |

Joyce with Paul Léon |

"Steeeeeeephen" |

|

|

|

Cardigan and jacket |

Joyce, Giorgio and Stephen |

Joyce with his grandson |

Colour Portraits (Gisèle Freund) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| [ See also Freund’s colour portrait of Sylvia Beach in 1939 - infra. ] |

[ top ]

It is worth emphasising that, during the period of three days covered by Freund’s photographic essay of 1938, Joyce was wearing two ties - one with a pattern of vertical stripes in a semi-check pattern, and another of a uniform colour, probably of silk - and, finally, a bow-tie for the Shakespeare & Company ’shoot’. It is also apparent from the pictures that, while he wore a cardigan with a striped tie under a russet dressing-gown in the majority of domestic scenes, he wore the same dressing-gown with a silk tie and without the cardigan in his mantelpiece parley with Philippe Soupault - certainly on a different day from the others and possibly on the first. Likewise, the family group under the Tuohy portrait of the writer’s father John Stanislaus Joyce certainly belongs to the garden group and possibly, therefore, to a separate day when Stephen and his parents came to visit. Certainly the boy and his father are dressed the same in each.

One might therefore suppose that this was the third day of shooting when the formalities of literary portraiture were over. Thus the dressing-gown (or ‘house-coat’ in American parlance) and the jacket are the indicators of a different day of shooting - rather than to suppose he shed it and donned a jacket on the same occasion. What is curious, indeed, is that, in the colour shoot a year later, he is wearing the same dressing-gown, cardigan and tie as in the majority of pictures taken by Giséle Freund in 1938. It is difficult to avoid the inference that he donned the same garb for Freund in 1939 which he had worn in 1938 - a fetching combination of wine-red dressing-gown, beige cardigan and checked tie which the new film technology was able to reveal for the first time.

If so, only two inferences are valid: either Joyce was fairly thread-bare and reduced to wearing the same cardigan under dressing-gown and jacket throughout all of a calendar year between Freund’s two professional visits to him, or else he purposely produced the same outfit on the second occasion. This seems entirely more likely since it speaks of Joyce’s sense of occasion and the characteristic symmetry of his mind requires such a measure. He had already decided how he wished to appear in Freund’s lens and was happy with the result in 1938 - happier still with the Time magazine photo of 1939. Everything about the three-day shoot shows him to be the master of his own stage-appearance. There is an air of bourgeois confidence about this man of letters, lording it in his own domain, relaxed yet elegant, - just as the bow-tie in the bookshop scene reveals him as a lord of language taking possession of his literary kingdom. What is more, the high visibility of a fine sculpted bronze clock and a handsome overmantle add to the sense that here is a natural denizen of the kind of drawing-room which his own pater had fecklessly exchanged for squalor as the family flitted from address to address in Dublin with a dwindling assortment of erstwhile family finery on the back of a horse-drawn dray.

Whether he wore a beige cardigan ever day in-doors is unclear but it is certain that the one he sports in the Freund shot of 1939 had lasted him since 1935, to judge by the oil portraits that Jacques-Emile Blanche made of him in that year. It was, apparently, his living-room outfit as a white medical coast was said to be his uniform when he was writing.

|

|

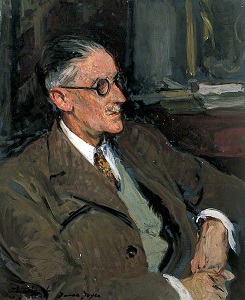

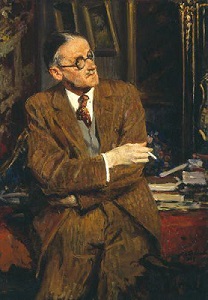

Oil portraits of Joyce in oil by Jacques-Emile Blanche (1935). |

[For further details about the Freund photo-shoots, see the letter from David Hurst - infra - from which

I have

gratefully

taken information in revising this page at the present time. BS 07.04.2017.]

|

Gisèle Freund

(self-port.) |

|

The apartment and garden where the black-and-white series was staged was certainly Joyce’s home at 7 rue Edmond Valentin in the 7ième Arrondisement, where he lived with his family from July 1934 to April 1939. (The location is confirmed by Freund in her memoir cited by David Hurst - as infra.) The sumptuous interior complete with mantelpiece and candelabra, as shown in the photo with Soupault where the proprietor borrows graceful support from the marble mantelpiece is quite in keeping with what is known of this elegant address in Baron Haussmann’s Paris.

Another photo in the series which shows Joyce departing through the double-doors of a gracious Parisian apartment building in company with Eugene Jolas, and with a concierge seated in the street outside, as concierges will on a fine day, most probably relates to the same building. Jolas is also present in a sunlit street-scene which is said to include Giséle Freund herself, though this seems improbable on any terms. Nor is the woman walkin along side them with a larger-than-attaché case either Sylvia Beach or Adrienne Monnier: she is an unknown extra whom fortune has allowed to play a permanent part in the history of European literature. It seems, in fact, that he is wearing the outfit that figures in the 1939 Shakespeare & Company shoot - and the very great likelihood is that Gisèle Freund is the photograper. (Anyone tempted to say that the diminutive female is Nora Joyce may stand in the corner till the end of the class.)

|

Street-scene, 1938 |

|

It does seem, in this picture [on the right] that he is already sporting the regalia so familiar from the 1939 session at Shakespeare & Company and which in turn seems modelled on the costume worn in the bookshop shoot when Ulysses was published in 1922. For all that, it cannot have been an entirely gleeful occasion, and there is something distinctly stagey about the pretend-conversation of the sitters and even more so about the flambouyant gestures of Adrienne Monnier, who appears to move around the room quite freely as if attempting to instil a natural atmosphere in the scene, while the other actors remain conspicuously sullen. Joyce himself resorts to scrutinising a framed picture - which should properly be the ‘Ulysses’ photograph, but isn’t. It is actually a portrait of Joyce - but none of the ones we have examined.

The fact that this moment is captured from front and back suggests, again, that the pose was held for long enough to allow the photographer to move to the other side of the room. Giséle Freund was well-known for her use of a Leica with 35mm film (and also for her experimental work with colour) and was probably using that that camera for all her shots of Joyce and friends. Indeed, the angle of the garden shots more or less confirms it. But the greater mobility of the miniature camera was paid back in terms of slower exposure speeds and therefore lower image resolution since faster films (i.e., larger grains of silver halide) had to be used to compensate for the lack of a steady tripod. Quite strong shadows suggest a photographic lamp set at 45% from the axis of the camera and the subject, and in one instance there is some consequent flaring on an adjacent wall.)

The Syvlia Beach who sits facing Joyce in Gisèle Freund’s bookshop picture is not the one who begged the honour of publishing Ulysses. In 1930 Joyce had forced her to relinquish her world-rights to the title - a deal was supposdely struck for $45K in advances from the Ameican publisher Random House in 1935 - he was peeved to learn that she had sold the manuscript of Stephen Hero - the draft version of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man which he had presented to her earlier in thanks for publishing the later novel. An exchange of letters with Theodore Spencer, the editor of that text, in late 1938 - and possibly before the bookshop photographs were taken - shows Joyce to be unhappy with the sale.

Accordingly, he had his amanuensis, Samuel Beckett, write back to Professor Spencer of New York State University at Buffalo that the autho believed the manuscript to have been sold by Miss Beach ‘in lots to different institutions in America [and that h]e feels that he can do nothing in the matter except to state this fact which he certainly can scarcely be blamed for not having foreseen at the moment of the presentation he made of it.’ [See Stephen Hero, ed. Theodore Spencer [1944] (London: Triad 1977, 1986), Preface, p.11.) If Joyce brought that mind-set to the photo-shoot with Beach in 1938, there was much to be brushed aside before the atmosphere of the 1922 picture could be recreated. |

[ top ]

Boris Lipnitzki portraits photos of Joyce in 1934 |

There exists another set of portrait pictures of Joyce - as distinction from the snapshots of friends and acquaintances or the photographs of journalists - and these were the work of Boris Lipnitzki, acting for the Roger Voillet photography agency and photographic archival firm. The photographs in question were taken either at 42 rue Galilée in the 16-ième Arrondisment or in 7 rue Edmond Valentin in the 7ième to which Joyce moved in July 1934.

|

| |

|

| |

The sitter portrayed in Lipnitzki’s portraits still is four years younger than the one who would submit to photograph record at the hands of Gisele Freund in 1938, but already the owner of same velvet dressing-gown (or ‘house-coat’) he would sport in many of images she took in his home at 7 rue Edmond Valentin. (We have a photo of his departure through the hall-door at that address among Freund’s images to prove it.) He may also be wearing the tie that appears in conjunction with that dressing-gown in a shot taken with Philippe Soupault at the mantel-piece - a frame distinguished from others in the series by the absence of a cardigan beneath the gown and the change of tie in question [see supra].

|

[ top ]

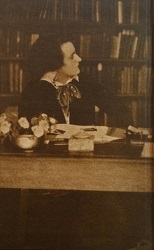

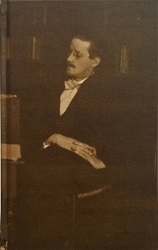

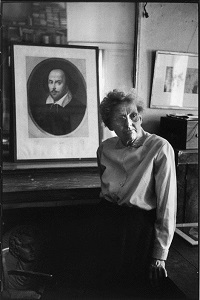

5: A Gallery of Portraits of Sylvia Beach (1887-1962) |

|

|

|

Numerous interior shots in the premises at rue de l'Odeon show that the fireplace wall

was filled with prints

- a very crowded shot of which appeared in Life magazine. |

|

|

|

The first shows Beach in rue Dupuytren in late 1919. Beach refused to sell a copy of Ulysses to a German

officer

and was sent to a detention centre after America joined the war. She continued living above her shop after it closed down. |

|

|

|

The first shows the composer George Antheil - friend and sometime tenant - climbing the facade; the

third is said to

have been taken by Gisèle Freud in 1939.

|

|

[ top ]

Sylvia Beach - Documentaries & Interviews on YouTube |

|

“I didn’t know much about literature ...” - see an interview with Sylvia Beach at YouTube -

|

|

Note - Beach records that Joyce spoke of ‘his buke’ with a Dublin accent

[online > 00:36].

|

The Trials of James Joyce (2000) |

formerly at

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9oDLbjZTh4w |

Roundtable Prods., Haddington Rd.,

Dublin |

|

[ The video became unavailable due to copyright

claim by CinemaGuildVOD; accessed 10.11.2014 ] |

|

|

[ top ]

| 6: Bibliography |

| A skeleton bibliography of works on Shakespeare and Company (Paris) |

- Sylvia Beach, Shakespeare and Company [1956] (NY: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich 1959; London: Faber & Faber 1960), and Do. [rep. edn.], introduced by James Laughlin (Nebraska UP 1991) [available online].

- Janet Flanner, Paris Was Yesterday, 1925-1939ed. Irving Drutman (NY: Viking 1972), 232pp. [her letters from Paris as “Genet” from The New Yorker in 1935; reps. NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich 1988 - partly searchable online; Houghton Mifflin 1989; rep. London: Virago 2003, 302pp.].

- Adrienne Monnier, The Very Rich Hours of Adrienne Monnier: An Intimate Portrait of Literary and Artistic Life in Paris between the Wars, trans. with intro. and commentaries by Richard McDougall, NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1976.

[Mercure de France,] Sylvia Beach (1887-1962): Hommages (Paris: Mercure de France 1963), 349pp. [contribs. T. S. Eliot,

T. S. Eliot, James Joyce, Marianne Moore, Henri Hoppenot, Jackson Mathews, Maurice Saillet, et al.

- Noel Riley Fitch, Sylvia Beach and the Lost Generation: A History of Literary Paris in the Twenties and Thirties (NY: W. W. Norton 1983; 1985) [available online].

- Keri Walsh, The Letters of Sylvia Beach (Columbia UP 2010) [available online].

|

| Also |

- Niall Sheridan, “Sylvia Beach” [interview], in Self Portrait [TV series] (2 Oct. 1962) - remastered copy available online @

|

| |

|

See also Appendices in separate window - attached. |

|

|

[ top ]

7: Postscript

| David Hurst writes ... |

I read with interest the article on the Ricorso site about the chronology of the photographs taken by (among others) Giséle Freund in 1938.

http://www.ricorso.net/rx/library/gallerys/authors/Joyce_JA/Beach_S/hmls/Shakespeare.htm [this page]

You state that the pictures all date from three days in 1938 when Freund was allowed to photograph Joyce over an extended period both at home and at Shakespeare and Co.

This is only partly true. The black and white photographs do date from three days in 1938 and were the result of a commission from Life magazine. However, the colour photographs were taken a year later in early 1939 when Freund was commissioned by Time to provide a colour photograph of Joyce to coincide with the publication of FW. There were two separate sessions on consecutive days. Apparently, after the first session the taxi taking Freund to the photo lab crashed and her camera was broken. She assumed the films were also ruined and managed to get Joyce to agree to a second session. In fact, they weren’t spoiled and she ended up with two entirely usable sets of colour images.

Joyce was reluctant to be photographed in colour as the lights that were necessary at that time were quite painful for him. He only agreed (according to Freund’s own account) because she hit on the ploy of using her married name, Bloom, when she wrote to him. The ever superstitious Joyce agreed at once – though the value of a colour photograph on the front page of Time to coincide with the publication of FW [Finnegans Wake] undoubtedly appealed to him too.

The text also says that the photograph of Joyce leaving a building with Eugene Jolas “probably relates to the same building [7 rue Edmond Valentin].” It undoubtedly does – Freund makes it clear in the caption to that photograph in her book “Three days with Joyce”, published in 1982. Indeed, the entrance to the building today is identical in every respect to the photograph.

I am aware this is (for most people) minute detail and is slightly peripheral to the main aim of the page, which is to date the photographs of Beach and the interior of her shop, but I hope it is of some interest.

David Hurst

|

[ Letter received by email, 13 March 2017.] |

| |

In a subsequent letter, David gives a more detailed account of the second occasion - which I copy here with the omission only of friendly remarks before and after:

|

| |

[...]

You are right: Freund herself is the source. She published two books of photographs which describe her sessions with Joyce. The first was a series of photographs of Joyce from the 1938 session, published as a monograph in 1982 (Three days with Joyce); the second was her autobiography (The World in my Camera), which devotes a chapter to the 1939 colour photograph sessions.

The anecdote about the taxi crash is more involved than my account below. According to Freund, Joyce banged and cut his head on one of the photographic lamps Freund was using on the first day. He “cried out as if he had been stabbed, clasping his hands to his forehead” and swore: “I’m bleeding. Your damned photos will be the death of me!” Freund described it as an “almost imperceptible scratch” which she dealt with by applying the cold steel of a pair of scissors, provided by Nora, to prevent any swelling.

Joyce was mortified at having sworn in front a woman. After the crash, Freund rang him up in tears and said: “ ‘Mr Joyce, you cursed my photos; you put some kind of bad Irish spell on them and my taxi crashed. I was almost killed and your photos are ruined. Now are you satisfied?’

“I heard Joyce sigh and guessed that I had not been mistaken: he must have cursed me and now felt responsible for the accident. Embarrassed, he made an appointment with me for another sitting the next day.

“When I arrived, he was full of remorse and very anxious to make amends.”

According to Freund, Joyce was immensely happy with the photograph on the front cover of Time and enjoyed telling the story behind it. She quotes him as telling friends: “I had said I would never be photographed in colour. Well, I was caught by Mrs B., not once but twice. She’s even cleverer than the Irish.”

|

|

[ Letter received by email, 3 April 2017 - ed. BS.] |

|

![Syvlia rue Duputyren [1919]](../jpegs/Duyptren/exterior/SylviaBeach1920.jpg)