James Joyce: Notes - Sundry Topics

| Textual History | Literary Figures | Joyce’s People | Sundry Remarks |

| Index |

| Joyce’s Paris homes |

| Why “Stephen Daedalus”? |

| Stanislaus Joyce writes: ‘My brother wrote [in a review of a title in the Pseudonym Library by one Valentine Caryl]: “After all a pseudonym library has its advantages; to acknowledge bad literature by signature is, in a manner, to persevere in evil.” When a year later his own first stories were published, he yield to a suggestion (not mine) and used a pseudonym, “Stephen Daedalus” [sic], but then bitterly regretted the self-concealment. He did not feel that he had perpetrated bad literature of which he ought to be ashamed. He had taken the name from the central figure of the novel Stephen Hero, which he had already begun to write. Against that name I had protested in vain; but it was, perhaps, his use of the name as a pseudonym that decided him finally on its adoption. He wished to make up for a momentary weakness; in fact, in order further to identify himself with his hero, he announced his intention of appending to the end of the novel the signature, Stephanus Daedalus pinxit. (My Brother’s Keeper, Faber 1958, p.239.) |

| Why “Stephen Hero”? |

| Entry for 2 Feb. 1904: [...] Finally a title of mine was accepted: Stephen Hero , from Jim’s own name in the book, "Stephen Dedalus". The title, like the book, is satirical.’ (The Dublin Diary; quoted in Hélène Cixous, The Exile of James Joyce, London: Calder 1972, p.224, citing Richard Ellmann, James Joyce [1959], p.152; see original in [Complete Dublin Diary of Stanislaus Joyce, ed. Healey, Cornell UP 1971; reiss. as The Complete Dublin Diary, ed. Healey, Dublin: Anna Livia Press 1992, p.12.) |

Note that this does not explain the adoption of the patronymic “Dedalus/Daedalus”, while that the adoption of the name “Hero” in the title of the novel is ascribed by Stanislaus to his own prompting elsewhere in MBK (p.12.) There exists evidence, however, that both James and Stanislaus Joyce would have taken the veiled allusion to Thomas Carlyle’s “Hero as Man of Letters” very much for granted as the basis of the allusion in the title, while further research suggests that Joyce took the name “Daedalus” from the last ode written by Giordano Bruno before his execution by burning. (See further under Giordano Bruno in Notes - attached.) |

| Some Additional Notes |

| ‘Dark mutinous Shannon waves’ in “The Dead” (Dubliners) - infra. Incidence of the word ‘soul’ in Joyce’s Dubliners - infra. James Joyce on the use of inverted commas in dialogue - infra. ] |

[ top ]

Sundry Remarks

Clongowes Wood: Herbert Gorman writes of the school’s influence and the events of its history on Joyce - ‘They speak again of the layer on layer of conflicting cultures, always with the dark mythos as foundation, that is the Island of today and the old mother of James Joyce. Even those far-away Brownes were important links in the long chain of Time that was to wind itself so unmistakably about the artist’s mind.’ Further, ‘This college was a particularly apposite selection for the imaginative boy. With the broad limits of its green-grassed demesne lingered vestiges of all the varying layers of civilisation, perceptible hints and reminders of the historical progression that had evolved the modern Ireland, this Parnell-dominated land, of young James Joyce.’ (q.p. Quoted in Peter Costello, James Joyce: The Years of Growth, London: Kylie Cathie 1992, pp.82-83.) [For remarks on the ‘three-sided’ view of life inculcated at Clongowes, see under Norah Hoult, supra.]

Clongowes Wood (2): Peter Costello prints a diary by Daniel O’Connell, Jnr. (1816-1897) held in the National Library, inside the cover of which are written the words: ‘Clongowes Wood College Clane Ireland Europe Eastern Hemisphere [sic] the World’, which he calls ‘a formula countless boys have since written.’ (Costello, Clongowes Wood: In A History of Clongowes Wood, 1814-1989, Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1989, p.35.)

“Leoville” (Carysfort Avenue, Blackrock) - see Gerard Quinn, ‘Joyce and Blackrock’, in Blackrock Society Proceedings (2004): ‘[...] the family moved from Bray to a less expensive house, 23 Carysfort Avenue, Blackrock, Dublin. The house, which is still called Leoville, stands at the intersection of Carysfort Avenue and the new Blackrock bypass. Joyce lived in this house from January 1892 till January 1893.’ (My Brother’s Keeper, pp.44-ff.; here p.77.)

Further, Quinn quotes Stanislaus Joyce: ‘I preferred the house in Blackrock [to] the one in Bray ... [I attended] school in Sion Hill Convent, but so far as I can remember my brother was left to his own devices at home.’ (Idem.)

‘I believe his first essays were written here at Leoville, Blackrock. ... I remember ... my brother writing in the afternoon till tea-time at the big leather-covered desk in the corner of the diningroom.’ (Idem.)

[ top ]

University College, Dublin (then the Royal University of Ireland), which Joyce attended autumn 1989-autumn 1902, occupied the former buildings of the Catholic University of Ireland, 1854-58, fnd. by Hierarchy under the rectorship of John Henry Newman and re-esetablished in 1879 with Royal University of Ireland as an examining body charged with publishing syllabi and setting papers for which candidates were prepared in Queen’s Colleges and others incl. Magee College in Derry. The College on St. Stephen’s Green was in the charge of members of the Society of Jesus [Jesuits], who filled most of the teaching posts. In 1908 UCD became part of a federal university consisting of the colleges in Cork [UCC], Dublin [UCD], and Galway [UCG], while the Queen’s University of Belfast was established as a separate university. This was the result of agitation largely on the part of the Graduate Association of University College, Dublin. In the 1980s St. Patrick’s College, Maynooth, which had been inaugurated in 1800 as a government-funded Roman Catholic seminary under the authority of the Catholic hierarchy, became a recognised university institution within the National University of Ireland.

Spiritual Paralysis: Joyce derive the term ‘spiritual paralysis’ from Thomas Carlyle, in The French Revolution, where it is also associated with the term mechanical, echoes in Joyce’s use of ‘formula and machinery’ in the ‘centre of vivification’ passage in Stephen Hero [SH75]. Examples of its use, with variants, in the works incl.: ‘the very incarnation of Irish paralysis’ -introducing epiphany (SH 188); Cf. ‘the soul of hemiplegia or paralysis which many consider a city’ [SL22]; ‘[...] entrust their wills and minds to others that they may ensure for themselves a life of spiritual paralysis’ [SH 132; my itals.]. Note that John Garvin points out that Joyce’s preoccupation with paralysis and GPI - that is, the ‘general paralysis of an insane society’ (in “1904 Portrait”) were rooted in his unsavoury family experience and speculates that John Stanislaus Joyce was a carrier and that May Joyce was infected with syphilis by him. (See further under Thomas Carlyle - supra.) Note: also the use (and typographical abuse) of ‘apgi’ in Becket’s Molloy [seeq.v.].

15 Usher’s Island, Dublin 8, being the rented home of the Morkans sisters where they taught music and thence the scene of Joyce’s story “The Dead”, was purchased by Brendan Kilty with a view to reopening on Bloomsday in 2001. In 2004 it was the setting of John Huston’s film version of Joyce’s famous story.

For sale (April 2017): The house at 15 Usher’s Island, now facing James Joyce Bridge on the south side of the Liffey, was built in about 1775 for Joshua Pim, who had his business next door at number 16. The house suffered from a fire and was saved by firemen, but afterwards boarded up until 2000 when it was bought by Dublin barrister and quantity surveyor Brendan Kilty who refurbished it over a four-year period, recreating Victorian interiors in some rooms which have since been used for Joyce-related events, including re-enactments of the Christmas dinner scene. In 2012, Kilty filed for bankruptcy in the UK with debts including £2.1 million owed to Ulster Bank in relation to the Usher’s Island house. The house, which is a protected structure, is now being sold on the instructions of receivers with a guide price of €550,000. Dublin City has no interest in taking on the house as a cultural venue. (See Livia Kelly [report], in The Irish Times, 12 April 2017 - online.)

7 Eccles Street: J. F. Byrne (Cranly in A Portrait) was living with his aunt at 7 Eccles Street in 1909, and was there visited by Joyce who assuaged his feelings of jealousy caused by Cosgrave’s intimation that he had been courting Nora secretly at the same time as Joyce in 1904. This Byrne dismissed as a malicious lie. (See Stanislaus Joyce, My Brother’s Keeper, 1958, p.209ff., and 211, n.2 [by Ellmann]). In 1902 he was living in Essex St. when Joyce was in Paris in 1902, and received a post-card from him which caused contention with Cosgrave (Lynch in A Portrait and Ulysses)on account of another containing dog-Latin comments on the ‘scorta’ of Paris as compared to the lyric “All day I hear the noise of waters / Making moan” sent to the former. [Idem., p.209.]

Note: No. 7, Eccles Street was demolished to make room for the extension of the Mater Misericordiae Hospital on 11 April 1967 and rescued by John Ryan, proprietor of the Bailey Pub on Anne St., where he erected it inside the foyer. The knocker - as noted by Austin Briggs - was in the pattern of the Anna Livia medallion on O’Connell St. Bridge. (See Austin Briggs, ‘The First International James Joyce Symposium: A Personal Account’, in Joyce Studies Annual, Summer 2002, pp.5-31.)

| Verbal allusions to Bloom’s address in Ulysses - e.g., |

|

| —See longer listing - attached. |

Why Eccles St.? Eccles Street was named for its developer Sir John Eccles [see under Hill St., infra], a member of the ‘Protestant ascendancy’. It happens to have been the dwelling-place of J. F. Byrne [Cranly], his college friend and hence the interior was known to him. By coincidence, it seems, Joyce set the first ‘epiphany’ on that street as recounted in Stephen Hero (p.188), and since the location of that first epiphany is at variance with the one recorded by Stanislaus Joyce in his diary, it is evident that the choice of location was actually imaginary. This begs the reason why. It is hardly plausible or sufficient to say that, in 1904 or 1905 when he wrote the ‘epiphany’ chapter of the abandoned novel, he had already envisaged a character like Leopold Bloom who would live there. Only his intervening experience of Trieste would supply him with the necessary Jewish-Irish co-ordinates for that. Instead, he seems to have chosen it for a purely lexical reason: the name Eccles St. resembles Gk. ecclesia or church (abbrev., eccles.) and thus corresponds to the christological dictum, ‘Thou art Peter and upon this rock I will found my church’ (Matt. 16:18). In fact, the primal epiphany is the foundation stone of Joyce’s literary-philosophical church and the coincidence that ‘one of those brown brick houses’ in Dublin’s lesser Georgian precincts should have serve both for that founding moment and its virtual apotheosis in the domiciliary arrangements of Leopold Bloom in Ulysses (where, incidentally, 7 Eccles St. is rented by him from the estate-owner as it was when J. F. Byrne’s mother had the door-key. [See fuller remarks on the Joycean ‘epiphany’

[ top ]

Epiphany (liturgy) - Surge Illuminare [1] - Book of Isaias (sometimes styles psalm) and Intriot of the Feast of the Epiphany: In The opening sentences of the ‘Epiphany’ episode of Stephen Hero set on Eccles Street, Dublin (pp.187-88), where we are repeatedly told that it was ‘a misty evening’ in the ‘misty Irish spring’ (p.187). Perhaps this is intended to echo the “Surge Illuminare” of the Introit of the liturgical feast on Jan. 6 of each year: ‘And the Gentiles shall walk in thy light, and kings in the brightness of thy rising.’ (Isaias 60.1-6).

Isaias 60.1-6 (Introit for Feast of Epiphany in the Catholic Missal): Arise, be enlightened, O Jerusalem; for thy light is come, and the glory of the Lord is risen upon thee. For behold, darkness shall cover the earth, and a mist the people: but the Lord shall rise upon thee, and His glory shall be seen upon thee. And the Gentiles shall walk in thy light, and kings in the brightness of thy rising. Lift up thy eyes and see [... &c.]. Cf. Vulgate: Surge, illuminare, Jerusalem, quia venit lumen tuum, et gloria Domini super te orta est, alleluia - Vulgate].

Note: Lumen gentium [light of the world] is the opening phrase of Psalm 232 in the Old Testament, and the epistemological title conferred on Jesus by St. Simeon in the Gospel According to St. Luke - viz.,

Nunc dimittis servum tuum, Domine, secundum verbum tuum in pace: Quia viderunt oculi mei salutare tuum Quod parasti ante faciem omnium populorum: Lumen ad revelationem gentium, et gloriam plebis tuae Israel. (Luke 2.32).

It is a title also claimed by Jesus himself in the Gospel According to St. John- viz.,

When Jesus spoke again to the people, he said, ‘I am the light of the world. Whoever follows me will never walk in darkness, but will have the light of life.’ (John, 8.12.)

Lumen Gentium is the title of the document propounding the principles of Vatican II, the creation of Pope John XXIII, otherwise called “The Dogmatic Constitution on the Church Lumen Gentium Solemnly Promulgated by His Holiness Pope Paul VI on Nov. 21 1964”. An English version is available online.

See New Marian Missal, ed. Sylvester Juergens (1960): ‘the liturgy makes use of the fire or light as a symbol of Christ, whose teaching enlightens the minds of the faithful and whose grace enkindles their hearts. Hence the importance of Feb. 2, and the blessing of the new fire and paschal candle on this day.’ (p.366). And vide ‘the kindler of the paschal fire’ [FW 128.34]

Note: The full Latin version as given in the Missal is ironically recited in the “Cyclops” episode of Ulysses (Penguin Edn. 1988, p.338). Here it serves to place Leopold Bloom in the role of Elijah, the promised messiah. In Stephen Hero it reveals Stephen in the character of a redeemer to his people, or one capable of reversing the condition in which they find themselves before his advent: ‘There was a mist upon the people’. In setting all of this at Eccles St., Joyce may also have been attempting to establish his own secular church of the imagination since ‘eccles.’ is the common abbreviation for ‘ecclesia’. This, notwithstanding the fact that the street is already named after Sir John Eccles. [BS]

[ See Notes > Phainos [1]- supra; also Hill St. Church - Sir John Eccles, infra. ]

Surge Illuminare [2] Coincidentally or otherwise, the same verse is quoted as an epigraph at the head of the Bethu Pathraic [Life of St. Patrick] by Muircu maccu Machtheni in the Tripartite Life of Patrick, issued by Whitley Stokes in 1887. In this way Joyce also - accidentally or otherwise - configures himself as a missionary to the Irish. It is possibly for this reason that he gives so large a place to St. Patrick in the scheme of Finnegans Wake - both in the sigla and in the Ricorso, where “The Colloquy of Balkelly and St Patrick” [FW614-15] figures among one of the first episodes of that book to have been composed. (See further St. Patrick, q.v., Stokes edition - especially remarks on the contest at Tara and the ‘wizard’s cloak’;, infra.)

| Epiphany Now! |

[1] - Jan Morris writes: ‘Nevertheless, to an outsider, what has happened to Ireland seems a 21st century benediction. It is a spectacular display of materialism, yes, but it is also a rare kind of epiphany: the moment when an entire nation, for so long a victim of cruel circumstances, is seizing history for itself at last, and starting all over again.’ (‘Ireland: Shiny Brash and Confident’, in The NY Times Magazine, 21 Nov. 2004, pp.72-79, 102; p.77.) |

[2] Thomas Harris describes the flash of intuition of his Italian police inspector who ‘once [he] experienced a moment of epiphany [...] that made him famous and then ruined him’ (Hannibal, London: Arrow Books 2000, p.128.) And further: ‘In that moment when the connection is made, in that synaptic spasm of completion when the thought drives through red fuses, is our keenest pleasure.’ (Ibid., p.134.) Bibliographical note on 1st edns.: Silence of the Lambs (1998); Hannibal (1999) [see COPAC]. |

[3] ‘At the unveilling of that threshold stone [of the Lyric Theatre, Belfast], fifteen months ago, Longley recalled his “decades of plays, hundred of epiphanies, thousands of hours of fun and enlightenment” at the Lyric.’ (See Jane Coyle, ‘A Dramatic Crucible Takes Shape’, in Irish Times, 8 Jan. 2011, Weekend, p.6; see further under Seamus Heaney, supra.) |

[4] Epiphany is defined as ‘the realisation of a great truth’ in the Alaskan episode of The Simpsons when Homer is instructed by an Inuit Indian wise-woman to return home to save the people of Springfield (Ill.) from a government plot - viz., Homer: ‘Okay, epiphany, epiphany... oh I know! Bananas are an excellent source of potassium!’ [Gets slapped.] (See Memorable Quotes from the Simpson Movie at IMDB.com [online; accessed 04.02.2009; 08.06.2011.]) |

[5] - Paulo Coehlo: ‘This week Mr. Coelho releases his latest novel, Aleph, a book that tells the story of his own epiphany while on a pilgrimage through Asia in 2006 on the Trans-Siberian Railway. (Aleph is the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet, with many mystical meanings.) While Mr. Coelho spent four years gathering material for the book, he wrote it in only three weeks.’ (See Julie Bosman, ‘A Word With A Best-Selling Author Who Gives His Work Away’, in New York Times, 26 Sept. 2011) - online. |

[6] Russell Brand: Brand reads out a letter from him to Boris Johnston on Facebook: ‘I think maybe you nearly cried at the bit where you said “Our NHS is powered by love” Did you? It looked like you did. It could have been crying at your own beauty type crying that my wife said I did when I proposed to her, or it could have been - I’m hoping it was - a kind of tearful epiphany. Was it an epiphany? [...]’ (Available at Facebook - online; accesssed 20.04.2020.) |

[7] Tim Peake: Asked if he ever feels he’s a disappointment to people, Britain’s first astronaut - said: “[W]hen people as me about religion or spirituality ... that’s just not me. [...] They want me to have had this incredible epiphany up there, this religious experience. And that just wasn’t the case. There’s a change of perspective, I suppose and a broadening of horizons.’ (‘Down to Earth’, in Guardian Weekly, 9 Oct. 2020, pp.40-44; p.42. |

[ top ]

Securus judicat orbis terrarum: John Henry Newman was led to doubt the truth of Anglican theology when he read Cardinal Wiseman’s article on ‘The Anglican Claim’ in the Dublin Review, citing the words of Augustine of Hippo against the Donatists, ‘securus judicat orbis terrarum [the verdict of the world is conclusive]’) - a formula suggesting that the teaching of antiquity is subject to a universal test. Newman wrote in response: ‘For a mere sentence, the words of St Augustine, struck me with a power which I never had felt from any words before [...] they were like the ‘Tolle, lege, - Tolle, lege,’ of the child, which converted St Augustine himself. ‘Securus judicat orbis terrarum!’ By those great words of the ancient Father, interpreting and summing up the long and varied course of ecclesiastical history, the theology of the Via Media was absolutely pulverised.’ (Apologia, Pt. 5; quoted on Wikipedia website Newman page online; accessed 28.08.2010.)

Superstition: Joyce believed 1921 to be a lucky year as adding up to 13 though that was also the sum of the year in which his mother died and was to be the sum of the date of his own death in 1929. Richard Ellmann writes in a footnote to James Joyce (1959): ‘Joyce knew the superstitions of most of Europe, and adopted them all.’ (Joyce, p.531.)

Trojan letters: An exchange of letters between Stephen Joyce and Danis Rose, editor of the Reader’s Edition of Ulysses, was printed in the Times Literary Supplement, 27 June & 12 July 1997, in which the former accuses the latter of ‘the rape of Ulysses’ and the latter answers, ‘there can only be alternative editions in which different ends are realised, either well or badly’, and ‘To conclude as Stephen James Joyce does, that I have “raped” Ulysses, is to admit to a profound incomprehension of the innate instability of Joyce’s text and of the rationale behind the present edition.’

|

[ top ]

Famine allusions in the works of James Joyce

| [Quotations extracted from works of James Joyce using Adobe Dreamweaver Search Command with digital copies [22.04.2021 ]. | |||||

|

|||||

Ulysses |

|||||

|

|||||

| Finnegans Wake | |||||

|

|||||

| Poetry | |||||

|

|||||

Critical Writings |

|||||

|

|||||

| Letters | |||||

‘I take the opportunity of letting you know (as you have no doubt heard) that I am about to leave Trieste. [...] I intend to do what Parnell was advised to do on a similar occasion: clear out, the conflict being between my dignity, and leave you and the catolicissime [Eileen and Eva] to make what they can of the city discovered by my courage (and Nora’s) seven years ago, whither you and they came in obedience to my summons, from your ignorant and famine-ridden and treacherous country. My irregularities can easily be made the excuse of your conduct. A final attempt at regularity will be made by me in the sale of my effects, half of which will be paid in by me to your account in a Trieste bank where it can be drawn on or left to rot according to the dictates of your own conscience. / I hope that your mind will be properly benefitted by the barter you have made of me and mine [...] and that, when I have left he field, you and your sisters will be able, with the meagre means at your disposal, to carry on the tradition I leave behind me in honour of my name and my country. (12 Jan. 1911; ‘Letters II 288-89; Sel. Letters, 1975, p.196; contains parenthetical details about Miss O’;Brien of London, aka, ‘the Cockney virgin’ and the ‘afflicted and the preoccupied Christographer of the Via dell’Olmo (on whom Fortnightly Review will shortly wait in person.’ Idem.] |

|||||

| Quoted in Christy L. Burns, ‘Parodic Irishness: Joyce’s Reconfigurations of the Nation in Finnegans Wake’, in Novel: A Forum on Fiction, Vol. 31, No. 2, Thirtieth Anniversary Issue: II (Spring, 1998), pp. 237-55 [my underline; available online; accessed 02.05.2021]. | |||||

[ top ]

Incidence of the word ‘soul’ in Dubliners -| Dubliners Concordance Online |

| “The Sisters” |

|

| “Araby” |

|

| “A Little Cloud” |

|

| “Ivy Day in the Committee Room” |

|

| “A Mother” |

|

| “The Dead” |

—“The Lord have mercy on his soul,” said Aunt Kate |

| [Formerly London Imperial College [www.doc.ic.ac.uk] - online; defunct at 04.11.2020] |

[ top ]

Joyce and Inverted Commas: Joyce stated his objection to the use of inverted commas (or ‘quote marks’) for dialogue in his works on several occasions, calling them ‘perverted commas’ on one of these. It can be inferred that the use of isolating diachronics of this type - more or less standard in Englsh fiction and echoed in the bracket marks of French and other romance languages - did not match his conception of the relationship between authorial narration and words spoken by the characters. Broadly speaking, from Dubliners onwards, it was Joyce’s practice to infuse the seemingly descriptive language, as well as those parts of the fiction-text which might be read as indirect speech, with the actual idiom of his characters and to avoid the convention of introducing and qualifying their spoken words with adverbs expressing the spirit or manner in which the words are spoken (e.g., “he retorted angrily’). This style of writing in Joyce can be treated as an evolution of the method associated with Gustave Flaubert - especially in Madame Bovary, where ‘le mot juste’ had much more to do with finding the word that the character would use in any retelling of their state of mind than with finding the happiest literary expression of the detail or characteristic conveyed. Not, therefore, ‘good writing’, but writing moulded to the contour of the subject. Inverted commas were nevertheless used in the first edition of the Dubliners stories due to the pubisher Grant Richards, and only removed in the Corrected Edition (ed. Robert Scholes, 1967). In dealing with the publisher of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, issued by Jonathan Cape in 1916, Joyce insisted that his use of dashes be observed after he had seen the galleys on which the inverted commas had been substituted for what he actually wrote in his manuscript. [BS 04.1.2020.]

Joyce on inverted commas: ‘I think the fewer the quotation marks the better. ... The “ ” are to be used only in the case of a quotation in full dress, I think, i.e., when it is used to prove or to contradict or to show [... &c.]’ (Letters of James Joyce, Vol. I, p. 263)

‘Then Mr. Cape and his printers gave me trouble [with A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man]. They set the book with perverted commas and I insisted on their removal by the sergeant-at-arms.’ (Letters of James Joyce, Vol. III, p. 99.)

—Quotations given at Literature Beta - Stack Exchange - online; accessed 04.11.2020.

Early printings: Students interested in comparing the first editions of Dubliners and A Portrait can look at those issued by B. W Huebsch of New York in 1914 and 1916 respectively. Huebsch states on his title-page (verso) that the books were ‘printed in the United States of America’ and claimed the US copyright accordingly, but in fact the sheets were printed by English publishers and sent to him to make his American editions - respectively by Grant Richards (Dubliners) and Jonathan Cape (A Portrait) both of London. It was common for sheets to be shared transatlantically in this way, though the imprint and even the title might be changed. It is clear from sample pages given above that the early editions of Dubliners based on Grant Richard’s sheets used inverted commas while the first edition of A Portrait used em-dashes before the characters’ utterances. Joyce’s preferred punctuation was by restored Robert Scholes for the Corrected Edtion of Dubliners issued in London Jonathan Cape in 1967. (Images from Internet Archive - Dubliners [online] and A Portrait [online] - accessed 04.11.2020.)

Further notice: It is apparent however that the Huebsch edition of Dubliners is not identical to the Grant Richards one one - as show my the variant lineation and content on pp.46-47 [see below], suggesting that the same sheets were not in fact used. Moreover, the broken word ‘cre-tonne’ at the bottom of p.14 in Huebsch’s (New York) printing is intact five lines above the bottom of p.46 in the Richards (London) edition. This suggests a different page-setting. However, the sheets for the London and New York editions of A Portrait published respectively by The Egoist Press and by Huebsch are identical. [More work required.]

| Some Pages from Early printings of Joyce’s Dubliners & A Portrait | |

|

|

| “Eveline”, in Dubliners (Huebsch 1916; 1917) | A Portrait of the Artist [...] (Egoist Press 1916) |

| [ Available in page view in Internet Archive online. ] | |

[ top ]

The word absence in Joyce’s works| ‘Absence, the highest form of presence’: Nothing is more common than the attribution of this apothegm to James Joyce and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916) is usually stated as the book where it appeared. Except it’s not there. Nor in Ulysses. Nor in the 1904 “Portrait Essay”. And nor is it in the critical writings. It seems to be a student response from the floor to Joyce’s oration on Feb. 1 1902 on the topic of “Drama and Life” and, not being in Stephen Hero, it is probably in a memoir by Curran or J. F. Byrne or another who remembers the occasion and is likely to be found in Ellmann’s biography of Joyce (1957; rev. 1984) which is out of reach at the moment. I have however found it on an internet blog located low down in the two-digit list of search results (mostly given over to the assertion that it is a witty quotation from Joyce) in the Google search returns: |

| The quotation: |

‘The time was 1 February, 1902: the place, the Literary and Historical Society room in University College, Dublin. The speaker, who would be twenty years old the following morning, 2 February, was James Joyce; and it does not take great perspicacity to observe that his style was not yet equal to the task of containing his vision. Dublin students, who are always great wits, had a wonderful time parodying “timid courage” - in the following days, but one of them (whose name has been, alas, lost) had even more fun with the final strophe, satirizing it as “absence, the highest form of presence.”’ |

|

|

| The ghosts in Ulysses |

|

[ top ]

Lodgers in Zürich: Joyce and Nora signed their names in the guest ledger at the Gasthaus Hoffnung, at 16 Reitergasse, Zurich, although an unmarried couple. The guest book in which they did so was destroyed when the River Sihl flooded in recent times. (See Bob Isaacson, ‘James Joyce Pilgrimage’, in Santa Barbara Independent [June 16 2004]; reprint on Isaacson’s blog page, online; accessed 13.08.2010. The informant is Fritz Senn.)

Type of our race: In arguing that Mangan is ‘the type of his race’ in as much as ‘[h]istory encloses him so straitly that even his fiery moments do not set him free from it’ [CW81], Joyce echoed the rhetoric of the other students at the Royal University in a letter to the Freeman’s Journal of May 1899 complaining that Yeats had portrayed ‘the type of our people [as] a loathesome brood of apostates’ [JJ69]. By contrast - and in a later riposte in the Portrait he identified the ‘type of his race’ as the ‘batlike soul’ of the woman who calls a ‘stranger to her door’ [AP]

First copy of Ulysses: Sylvia Beach collecting 2 copies of the Shakespeare & Co. First Edition of Ulysses sent to Paris by Maurice Darantiere in Dijon [var. Marseilles] and collected from the guard of the Dijon-Paris train at 7 a.m. (copies nos. 901 & 902); JAJ signs and presents first copy to Nora, who offers to sell it to Arthur Power; further copies arrive from Dijon (nos. 251 & 252), 5 Feb. [Selected Letters, 1975, p.288]; HSW lodges the first copy [presum No. 1] with National Library of Ireland [query date].

Homerics: Joyce’s reading for Ulysses included Charles Lamb’s Adventures of Ulysses [1803] but also Victor Bérard’s Did Homer Live? (NY 1931). [See Stuart Gilbert, James Joyce and the Making of Ulysses.]

Note: The text of Charles Lamb’s Adventures of Ulysses is available for use by Joycean readers in the RICORSO Library > Irish Classics - as attached.

Molly/antidote: For Harry Blamires, Molly is an antidote to the sterility of Dublin when Joyce takes a ‘plunge into the flowing river’ of her mind: ‘if we have hitherto been exploring the waste land, here are the refreshing, life-giving waters, that alone can renew it.’ (Guide, q.p.)

Ben Bloom Elijah: the ascent of Bloom ‘at an angle of forty-five degrees like a shot [shit] off a shovel’ is modelled on the Bible (2 Kings, 2:11): ‘Behold, there appeared a chariot of fire, and horses of fire, and parted them both asunder; and Elijah went up by a whirlwind into Heaven.’

Film: Joseph Strick, Ulysses (q.d.), with Milo O’Shea, et al.; also Nora (2000), a film, with Susan Lynch in title role and Ewan McGregor as the young Joyce;, Note also Fionnula Flanagan as Molly Bloom in James Joyce’s Women (1985).

[ top ]

Union Jacks: speaking of her conversations in Vichy with Valéry Larbaud, Patricia Hutchins writes: ‘I was told, a little ruefully, how he had given instructions for his special copy of Ulysses to be bound “with the colours of Ireland”’ as part of the cover, and it had arrived with a Union Jack ensconced there. “That raises a nice point”, I laughed. “For the book was written under the British regime, or about that period anyway. And Joyce was not what one would call a nationalist; he stood apart from it all. Indeed, I think it best to leave it there.” (James Joyce’s World, London: Methuen 1957, p.195.) Note also that Bloom has a ‘compactly furled Union Jack’ inside his living-room door in Ulysses (Bodley Head Edn., 1966, p.829.)

“Finnegan’s Wake” [the ballad]: ‘Mickey Maloney raised his head, / When a gallon of whiskey flew at him; / It missed, and falling on the bed/The liquer scattered over Tim / Och, he revives! See how he raises!’/And Timothy, jumpoing from the bed,/Sez, “Whirl your liquor round like blazes - / Soulds ot the devil! D’ye think I’m dead?’

Cad with a Pipe: An allusion to the ‘cad with a pipe’ (from Joyce’s Finnegans Wake), in Beckett’s Watt was identified by David Hayman. Arsene recalls meeting Mr. Ash on Westminister Bridge on a day when ‘it was blowing heavily’ Mr. Ash loosens layers of heavy-weather gear, consults his ‘gunmetal half-hunter’ and offers without being asked the time of ‘seventeen minutes past five exactly, as God is my witness’ [120]. Cf. Joyce: ‘the wind billowing across the wide expanse’ and ‘clad in layers of antiquated and vaguely military gear.’ (See Hayman, ‘A Meeting in the Park’, JJQ, 8, 1971; quoted in John Harrington, The Irish Beckett, 1991, p.117.)

The “N” word: Joyce used the word ‘nigger’ in its pejorative sense as referring to blacks - African, African-American and so forth - in a letter to Stanislaus Joyce: ‘I wonder when learning it [Danish] is it necessary to keep a good-sized potato in each cheek. You said it was like a nigger speaking German but it is more like Mr. O’Connell (Bill) speaking Dutch.’ (Selected Letters, 1975, p.97.) Note also that John Stanislaus Joyce had a dog called “Nigger” in 1907.

Irish Racing World: Among the horses featured as winners at long odds in the poster of The Pink’Un [properly The Sporting News] which figures in the well-known photograph of Joyce at Shakespeare and Company is Killeen, a winner at 7-2. The other three horses listed under the caption ‘MORE WINNERS LIKE’ are Sargon (5-1), Square Dance (9-2) and Kilvemnon (7-2). The photograph serves as a cover of the Penguin Annotated Students Edition of Ulysses, intro. Declan Kiberd (1992). Note that Killeen is the name of the home of the Dunsany family (Lord Fingall) in Co. Meath.

Portraits (of James Joyce): Seán O’Sullivan, drawing with water colour on paper, signed Paris 1935 [NGI]; also black ink, signed Wyndham Lewis, 1921; presented to NGI by Harriet Weaver, 1951; Patrick Tuohy, seated figure, in oil; Des MacNamara, papier maché bust, lent by Allen Figgis and chalk on grey rag paper by Sean O’Sullivan (see Anne Crookshank, Irish Portraits, Ulster Museum 1965); steel head by Conor Fallon; images by Louis le Brocquy [q.v.]; port. on £20 banknote by Robert Ballagh; line dawing by Brancusi [pbk. cover Ellmann, James Joyce, 1959]; Brian Grimwood, cover ill. to Beja, James Joyce, a Literary Life (1992); Joyce during early Zurich period, 1917, phot. in the Croessmann Coll., S. Ill. Univ. Library, dustjacket Exiles (J. Cape 1952; rep. 1972, 1974); a bust of James Joyce by Jo Davidson is reproduced in Thomas Connolly, ed., Scribbledehobble. See also “Three studies of Joyce” by Louis le Brocquy - ‘Studies Towards an Image of James Joyce’, in The Crane Bag, 2, Nos. 1 & 2 (1977) - viz., “Study 61”, p.1; ““Study 63”, p.8; “Study 60”, p.192.

Ulysses in Nighttown: Award winning adaptation of the “Circe” episode of Ulysses by Marjorie Barkentin with incidental music by Peter Link. The play opened Off-Broadway in 1958 with Zero Mostel who Mostel an Obie Award for it. It was revived in Philadelphia in 1974 and played 26 nights, afterwards transferring to the Winter Garden Theatre on Broadway (15 Feb. 1974), where it ran for 69 nights, with Mostel, Fionnuala Flanagan, Gale Garnett, Tommy Lee Jones and David Ogden Stiers in the cast, earning 8 Tony Award nominations - including one for Flanagan - and one Tony winner for the lighting by Jules Fisher.

[ top ]

Librarian’s-eye view: Ulysses (1922) is listed from the standpoint of the library catalogue - i.e., Library of Congress taxonomic listings - as a novel in English dealing with with ...

|

||||||

| ... each of which constitutes a searchable category in COPAC. | ||||||

Jim the Penman (1886) is the title of a successful melodrama about the forger James Towsend Saward, who specialised in forging cheques in London and later in Great Yarmouth - where he was arrested through the incompetence of an accomplice and tried in March 1857, being sentence to penal servitude in Australia. The play is by Sir Charles Young [7th Baronet], a barrister; a silent film was made of it by the Famous Players Film Company in 1915 and released through Paramount Pictures. [See Wikipedia - online]. Joyce’s Shem the Penman in 1.vii of Finnegans Wake, with his “epical forged cheque” (viz., Ulysses) is an allusion to him besides it autobiographical and satirical function.

[ top ]

Gordon-Bennett: for information about the original event featured in After the Race - an event which Joyce covered for the newspapers - see Gordon-Bennett supplement to Black’s Guide to Ireland: with special information for visitors to Ireland in connection with the great automobile contest on July 2nd, compiled by R. T. Lang [Irish Automobile Fortnight; Black’s Guide to Ireland (London: Adam & Charles Black 1903), 3pp. [COPAC listed copy in Oxford).

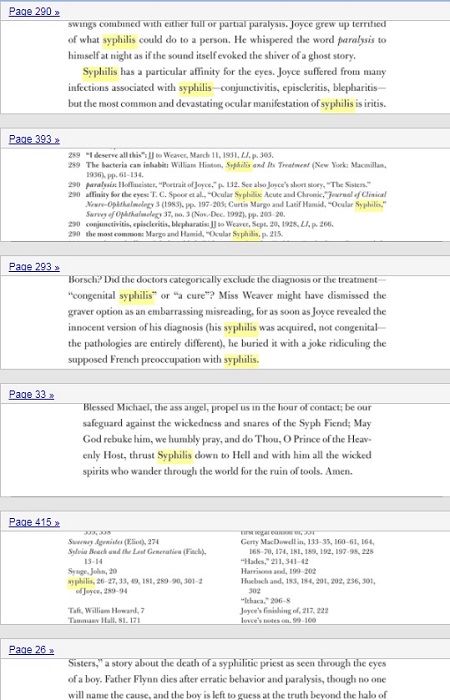

| Did Joyce have syphilis? | |

|

|

| See Ferris, op. cit. (1995) - Amazon online; also Guardian review by Alison Flood (3 June 2014) - online; both accessed 25.09.2017. | |

|

|

| Search for <syphilis> in Ferris, James Joyce and the Burden of Disease (Kentucky UP 1995) - Google Books [03.03.2023]. |

Joyce’s composers: “For me there are only two composers. One is Palestrina and the other is Schoenberg.”’ (See Jim Samson, Music in Transition: A Study of Tonal Expression and Atonality 1900-1920, London : J. M. Dent & Sons 1977, p.194; quoted in Jonathan McCreedy, MA Diss., UUC 2008.)

[ top ]

Nighttown/Monto: The Monto, after Montgomery Street, was the common name for the area in North Central Dublin prostitution was permitted during the period of Ulysses. Frank McNally quotes the Encyclopaedia Britannica (1903 Edn.): ‘Dublin furnishes an exception to the usual practice of the United Kingdom. In that city police permit open “houses” confined to one area, but carried on more publicly than even in the southof Europe or Algeria.’ He explains that ‘a combination of economic hardship and militarisation of Dublin helped feed the growth of a sex industry, to which ‘Monto’ became central’, and adds erroneously: ‘The area features famously in Ulysses, being the scene where, in a misunderstanding over a woman, Stephen Dedalus is assaulted by a British squaddie.’ (“An Irishman’s Diary” [column], Irish Times, 7 May 2011).

The Catechism [RC] (1917) - Extracts: Q. What is sin? A. Sin is any wilful thought, word, deed, or omission contrary to the law of God. Q. What is mortal sin? A. Mortal sin is so called, because it kills the soul be depriving it of its true life, which is sanctifying grace, and because it brings everlasting death and damnation to the soul. [Q. What is venial sin?] A. Venial sin is does not deprive the soul of sanctifying grace, or deserve everlasting punishment, but it hurst the soul by lessing its love of God, and disposing it to mortal sin. The Scripture says, He that contemneth small things shall fall by little and little. (Eccles. xix. i.) [...] Q. Is it a great misfortune to fall into mortal sin? A. To fall into mortal sin is the greatest of all misfortunes. [...] f we fall into mortal sin we ought to repent sincerely, and go to confession as soon as we can. If we cannot go to confession soon after falling into moratl sin we ought to excite ourselves to perfect contrition, with the intention of going to confession. [24] [...] They who die in mortal sin go to hell, for all eternity. [24] (For longer extracts, see attached.)

[ top ]

Bloom’s Library: the collection of books made visible through the mirror of Bloom’s living room on their two shelves are: Thorn’s Dublin Post Office Directory (for 1886); Denis Florence M’Carthy’s Poetical Works; Shakespeare’s Works; The Useful Ready Reckoner; The Secret History of the Court of Charles II; The Child’s Guide [see details] ; William O’Brien, When We Were Boys; Thoughts from Spinoza; Sir Robert Ball, The Story of the Heavens; Ellis’s Three Trips to Madagascar; A. Conan Doyle, The Stark-Munro Letters; “Viator”, Voyages in China; Philosophy of the Talmud; Lockhart’s Life of Napoleon; Gustav Freytag, Soll und Haben; Hozier’s History of the Russo-Turkish War; William Allingham, Laurence Bloomfield in Ireland; A Handbook of Astronomy; The Hidden Life of Christ; In the Track of the Sun; Eugene Sandow, Physical Strength and How to Obtain It; written in French by F. Ignat. Pardies, Short but yet Plain Elements of Geometry [trans. John Harris, MDCCXI]. (Ulysses, Bodley Head Edn. 1965, p.832.)

| The Child’s Guide to Knowledge; being a Collection of / Useful and Familiar Questions and Answers on Everyday Subjects / Adapted for Young Persons, / and arranged in the most simple and easy language / BY A LADY / forty-sixth edition / London Published by Simpkin Marshall, & Co., / and Sold by All Booksellers MDCCCLXXII. Price Three Shillings. The Rights of Translation and Reproduction Reserved. [See online image of title-page and some contents at Tony Thwaites’s “Ulysses Tour” page (The University of Queensland, Australia) - link] |

Portraits (family) received by James Joyce from his father incl. those of Charles O’Connell and wife by John Comerford (1771-1832); one of James A. Joyce and his wife Ellen by William Roe (?1800-?1850); another of John Stanislaus Joyce in 1866 [aetat. 16; q. pinct], to which Joyce added another of his father by Patrick Tuohy, who also painted the writer; all now in Lockwood Memorial Library, Buffalo Univ.; John Stanislaus Joyce owned framed engraving of Galway Joyces’s motto [i.e., not his own family: an eagle gules volant in a field argent displayed.(See Ellmann, James Joyce, 1959 & edns.) Note, There is also a photo-port of May Joyce in early married life in the National Library of Ireland; a port. of Joyce in sailor outfit preparing to leave for Clongowes, aetat. six-and-a-half; as an infant, in S. Illinois Univ. Library. (See Peter Costello, The Years of Growth, 1992, ills.) The photograph of Joyce in yatching shoes is by Con Curran, taken at his father’s house, 211 Cumberland Place [now 211 N. Circular Rd].

Portraits: A photograph purportedly of May Joyce, taken by M. Glover of Dublin and presented to the National Library of Ireland by Kathleen Murray as her aunt, was thought by Stanislaus to be that of an actress she resembled. In writing of it, Patricia Hutchins notes that a faded photography of Maud Branscombe, actress and professional beauty, mentioned in Ulysses. (Bodley Head Edn. p681) (See Patricia Hutchins, James Joyce’s World, 1957, p.155, n.2.

No Joyceans, Please! (TCD): Philip F. Herring, writing of the 2nd International Symposium in Dublin (1969), quotes a newspaper article by Mary McGoris as reporting that the Moyne Institute [of Bacteriology] in Trinity College, the hosting institution, bore a notice on the front doors stating: “Do Not Enter”, and another inside stating “No Joyceans Upstairs”. He goes on to quote her comments on the Symposium, which is said to be populated mostly by Americans: ‘Though there are some references in the programme to Dubliners and Portrait of the Artist, most of the speakers concentrate on the more recondite works, with particular emphasis on Finnegans Wake [...]’. (See Herring, ‘Some Thoughts on the Second International James Joyce Symposium’, James Joyce Quarterly, Fall, 1969, pp.3-9, p.5; available at JSTOR - online.)

Note: the holder of the Chair of Microbiology at Trinity College Dublin in 1969 was [Frederick] Stanley Stewart, FTCD, MRCPI, successor to Joseph Bigger who was the son of the Irish parliamentarian Isaac Bigger. (BS of Ricorso is a son of FSS.]

Joyce’s Encyclopaedias - Stanislaus Joyce writes: ‘In Trieste he once told me that he preferred the Italian to the British Encyclopedia because it contained so much useless knowledge that interested him. [...]. (The Early Joyce: The Book Reviews, 1902-1903, Colorado Springs: The Mamalujo Press 1955, p.43; quoted in Critical Writings of James Joyce, ed. Ellsworth Mason & Richard Ellmann, Viking Press, 1966, p.135.) [For further remarks on Pragmatism, see under Stanislaus Joyce, infra.]

[ top ]

Volta cinema - Mary St., Dublin: JAJ acquired a lease to premises at 45 Mary Street, secured a licence for performances, and opened to the public on 20 December 1909 after some renovations to the property - naming it after the Volta cinema in Trieste which he frequented. Surviving reviews suggest a mixed reception, quibbling with the continental bias of the fare. Thus the Evening Telegraph ‘Yesterday at 45 Mary St. a most interesting cinematograph exhibition was opened before a large number of invited visitors. The hall in which the display takes place is most admirably equipped for the purpose, and has been admirably laid out...The chief pictures shown here were “The First Paris Orphanage”, “La Pourponierre” [sic], and “The Tragic Story of Beatrice Cenci.” The latter, although very excellent, was hardly as exhilarating a subject as one would desire on the eve of the festive season.’ [See Irish National Archive, list of cinemas in 1922 - when the Lyceum had succeeded the Volta at the same location - online.]

Invincibles: The Irish National Invincibles perpetrated the Phoenix Park Murders of 6 May 1882. References to that event permeated Ulysses, but notably the “Eumaeus” chapter where the character called “Skin the Goat” is falsely supposed to be a denizen of the cabmen’s shelter. Early on, in All Hallows Church, Westland Row, Bloom mistakenly cites Peter Carey, the brother of the betrayer, when he reflects ‘That fellow that turned Queen’s evidence on the invincibles he used to receive communion every morning. This very church. And plotting that murder all the time’ (81:26-28). [...] (For longer version of this note, see under Charles Stewart Parnell - infra, and note fuller details of the Invincibles above it at the same location.)

Hill St. Church (fnd. by Sir John Eccles - from whom the name Eccles St. derives) - Corporation signage reads: ‘Founded in 1714 by Archbishop King and Sir John Eccles, as a chapel of ease it was converted into an open space by Dublin corporation at a cost of £700 and formally opened by the Lord Mary on 1894. The tower remains standing and the graveyard is now a playground.’ Further:

St George, Hill St. (Little St. George’s)

There was a medieval parish of St George, the church of which stood in George’s Lane, near the junction of the present Exchequer Street and South Gt. George’s Street. But the parish became extinct at an early date. The local landord, as a chapel-of-ease to St Mary’s in which parish it was till the new parish was created in 1894 [sentence sic.] It was about 65 feet long by 10 feet wide, an extended east of the tower which still remains. It must have been a plain building, as the tower is of rought stone quasi-gothic type. It continued to be used as a church well into the xixth [sic] century, but all save the tower was demolished in 1894. The graveyard was at a more recent date turned into a playground, but many tombstones remain upright round the edges. The bell and one monument are to be found in the new St. George’s, Hardwick Place. (q.v.) [Source not stated.]

[ top ]

‘That other world’: In Martha Clifford’s letter to “Henry Flower” - the alias that Leopold Bloom uses to conduct a clandestine correspondence inaugurated in the “personal column” of The Irish Times which he collects from the Westland Row Post Office in the “Lestrygonians” episode of Ulysses - she writes: ‘I called you naughty boy because I do not like that other world [sic]. Please tell me what is the real meaning of that word. Are you not happy in your home you poor little naughty boy?’ (Ulysses: Corrected Edition, ed. Hans Walter Gabler (Penguin 1984, 5.243.)

In the immediately-following “Hades” episode, Bloom - by now in Glasnevin Cemetary attending the funeral of Patrick Dignam, reflects: ‘There is another world after death named hell. I do not like that other world she wrote. No more do I. Plenty to see and hear and feel yet.’ (Ibid; U6.1001.) In Joycean commentary, Martha’s mistake is widely regarded as a Freudian slip - conflating her excitement and anxiety about an improper word that he has used with her fears of punishment in an afterlife.

In May 1998, a conference was held at the Princess Grace Irish Library in Monaco under the title “That Other World: The Supernatural and Fantastic in Irish Literature”, resulting in a 2 vol. publication edited by Bruce Stewart, the then Literary Directory of the Library (1998-2004). The title was prompted by Denis O’Donogue when he attended a previously PGIL conference on W. B. Yeats.

Lost in translation: In the standard Portuguese translation of Ulysses by Bernardina da Silveira Pinheiro, Martha’s mistake has fail to come across if only because it is impossible to render it in another language, hence: ‘Eu o chamei de menino levado porque no gosto daquele outra planeta.’ No allusion to the problem is made in the extensive notes by Flavia Maria Samuda attached to the translation. (Pinheiro, trans., Ulisse, Rio do Janeiro: Alfaguara 2007, p.108; Notes, 843ff.]

[ top ]

Elias Heretic? In Stephen Hero, the protagonist reads at Marsh’s Library where he encounters the works of Elias and Joachim who are said to ‘relieve the naif history’ of St Francis whose ‘love-chains’ he has been reading. [SH, 181.] Who is Elias? This is possibly an artful transposition of the name of Elias Bouhéreau, the first Librarian at Library, a Huguenot appointed by Archbishop Narcissus Marsh in 1701 - or else it is Ellies du Pin, the author of Nouvelle bibliothèque des auteurs ecclésiastiques, a compendium of Church Fathers and Councils which was rapidly translated by William Wotton as A New History of Ecclesiasticall Writers (1692-99) - a copy of which is listed in the catalogue of Marsh’s Library as Record 11796. [See Catalogue - online].

Work-wear: ‘In his late twenties, James Joyce wore a white coat while he worked. He’d put it on, climb into bed, and compose his work with a blue pencil. His sister Eileen noted that the coat “gave a kind of white light” that helped him see the page. Joyce battled eye diseases throughout his life. As his sight worsened, the resourceful author magnified his entire creative process, writing intricate sentences with coloured crayons on large pieces of cardboard.’ (Cited on James Joyce Facebook page at 6 June 2013 - online.)

Coining it: A €10 coin issued by the Irish Central Bank on 10 April 2013 incorporates a misquotation from the “Proteus” episode of Ulysses, inserting the relative pronoun in the second sentence: ‘Ineluctable modality of the visible: at least that if no more, thought through my eyes. Signatures of all things that I am here to read.’ [my italics]. A letter from the Joyce Estate to Patrick Holohan, director of the Bank, suggested donating the €25,000 to a charity as compensation for the “insult’ perpetrated against the memoir of Joyce. (See Henry McDonald, in Guardian, 11 April 2013; Terence Killen, Irish Times, 25 May 2013.)

Price of Ulysses: Joyce reproachfully told Aunt Kathleen Murray in a letter, ‘In a few years copies of the first edtion will probably be worth £100 each, so experts say.’ (Letter of 23 Oct. 1922, sent from Hôtel Suisse, Nice.) On 26 Nov. 1957, Middleton Murry’s copy was duly sold for £140. (See Richard Ellmann, James Joyce, rev. edn. 1982, p.539 & n.)

[ top ]

| The Volta Cinema: The Volta Cinema at 45 Mary Street, Dublin, opened on 20 December 1909, with this programme (correct original language titles and credits in brackets): | |

|

|

The Volta seated about 600-700 (200 kitchen chairs were at the front for those paying the top prices). It was a simple shop conversion i.e. no racking, and only the plainest of comforts. Doors opened at 5.00 pm and there were continuous 35 to 40-minute programmes every hour up to 10.00 pm. One extraordinary feature was that the titles of the films were all in Italian - Joyce received the films direct from the Trieste source rather than through English film exchanges, and so handbills were given out with English translations. Music was supplied by a small string orchestra, led by Reginald Morgan. Tickets were 2d, 4d and 6d, children half price. / Joyce did not stick around for long, leaving the cinema in the hands of one Francesco Novak [...] |

|

| [See Luke McKernon, ‘Visiting the Volta’, on Bioscope [Blog] - 6 May, 2007; noticed by Simon Loekle on Facebook, 11.03.2015.] |

Trieste Joyce School - Summer of 2013: The 17th Annual Trieste Joyce School will take place at the University of Trieste from 30 June to 6 July 2013. Speakers will include Mark Axelrod (Chapman University), Giuliana Bendelli (Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milan),William Brockman (Penn State University), Ron Ewart (Zurich James Joyce Foundation), Catherine Flynn (University of California, Berkeley), Liam Harte (University of Manchester), Edna Longley (Queen’s University Belfast) John McCourt (Università Roma Tre), Eve Patten (Trinity College Dublin), Laura Pelaschiar (Università di Trieste), Fritz Senn (Zürich James Joyce Foundation), Gerry Smyth (Liverpool John Moores University), Luke Thurston (Aberystwyth University). Michael Longley will be writer-in-residence. A note has been received from Michael Higgins, President of Ireland: "I am pleased to hear that Trieste, so beloved of Joyce himself, will welcome back Joyce scholars and lovers for the 17th time this year to its renowned summer school. I extend my congratulations to Laura Pelaschiar for her direction of this imaginative programme."(6 February 2013). Limited number of scholarships available. For further information please write to [email] or visit the website at www2.units.it/triestejoyce/] or Facebook [online].

| [back ] | [ top ] | [ next ] |