Charles Robert Maturin, Melmoth the Wanderer (1820)

CHAPTER XXXI

There is an oak beside the froth-clad pool,

Where in old time, as I have often heard,

A woman desperate, a wretch like me,

Ended her woes!—Her woes were not like mine!

* * * *

Ronan will know;

When he beholds me floating on the stream,

His heart will tell him why Rivine died!

HOME’S FATAL DISCOVERY

“The increasing decline of Elinor’s health was marked by all the family; the very servant who stood behind her chair looked sadder every day—even Margaret began to repent of the invitation she had given her to the Castle.

“Elinor felt this, and would have spared her what pain she could; but it was not possible for herself to be insensible of the fast-fading remains of her withering youth and blighted beauty. The place—the place itself, was the principal cause of that mortal disease that was consuming her; yet from that place she felt she had less resolution to tear herself every day. So she lived, like those sufferers in eastern prisons, who are not allowed to taste food unless mixed with poison, and who must perish alike whether they eat or forbear.

“Once, urged by intolerable pain of heart, (tortured by living in the placid light of John Sandal’s sunny smile), she confessed this to Margaret. She said, “It is impossible for me to support this existence—impossible! To tread the floor which those steps have trod—to listen for their approach, and when they come, feel they do not bear him we seek—to see every object around me reflect his image, but never—never to see the reality—to see the door open which once disclosed his figure, and when it opens, not to see him, and when he does appear, to see him not what he was—to feel he is the same and not the same,—the same to the eye, but not to the heart—to struggle thus between the dream of imagination and the cruel awaking of reality—Oh! Margaret—that undeception plants a dagger in the heart, whose point no human hand can extract, and whose venom no human hand can heal!” Margaret wept as Elinor spoke thus, and slowly, very slowly, expressed her consent that Elinor should quit the Castle, if it was necessary for her peace.

“It was the very evening after this conversation, that Elinor, whose habit was to wander among the woods that surrounded the Castle unattended, met with John Sandal. It was a glorious autumnal evening, just like that on which they had first met,—the associations of nature were the same, those of the heart alone had suffered change. There is that light in an autumnal sky,—that shade in autumnal woods,—that dim and hallowed glory in the evening of the year, which is indefinably combined with recollections. Sandal, as they met, had spoken to her in the same voice of melody, and with the same heart-thrilling tenderness of manner, that had never ceased to visit her ear since their first meeting, like music in dreams. She imagined there was more than usual feeling in his manner; and the spot where they were, and which memory made populous and eloquent with the imagery and speech of other days, flattered this illusion. A vague hope trembled at the bottom of her heart,—she thought of what she dared not to utter, and yet dared to believe. They walked on together,—together they watched the last light on the purple hills, the deep repose of the woods, whose summits were still like “feathers of gold,”—together they once more tasted the confidence of nature, and, amid the most perfect silence, there was a mutual and unutterable eloquence in their hearts. The thoughts of other days rushed on Elinor,—she ventured to raise her eyes to that countenance which she once more saw “as it had been that of an angel.” The glow and the smile, that made it appear like a reflexion of heaven, were there still,—but that glow was borrowed from the bright flush of the glorious west, and that smile was for nature,—not for her. She lingered till she felt it fade with the fading light,—and a last conviction striking her heart, she burst into an agony of tears. To his words of affectionate surprise, and gentle consolation, she answered only by fixing her appealing eyes on him, and agonizingly invoking his name. She had trusted to nature, and to this scene of their first meeting, to act as an interpreter between them,—and still even in despair she trusted to it.

“Perhaps there is not a more agonizing moment than that in which we feel the aspect of nature give a perfect vitality to the associations of our hearts, while they lie buried in those in which we try in vain to revive them.

“She was soon undeceived. With that benignity which, while it speaks of consolation, forbids hope—with that smile which angels may be supposed to give on the last conflict of a sufferer who is casting off the garments of mortality in pain and hope—with such an expression he whom she loved regarded her. From another world he might have cast such a glance on her,—and it sealed her doom in this for ever. * * * *

* * * *

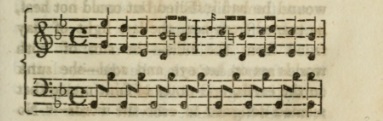

“As, unable to witness the agony of the wound he had inflicted but could not heal, he turned from her, the last light of day faded from the hills—the sun of both worlds set on her eye and soul—she sunk on the earth, and notes of faint music that seemed designed to echo the words—“No—no—no—never—never more!” trembled in her ears. They were as simple and monotonous as the words themselves, and were played accidentally by a peasant boy who was wandering in the woods. But to the unfortunate, every thing seems prophetic; and amid the shades of evening, and accompanied by the sound of his departing footsteps, the breaking heart of Elinor accepted the augury of these melancholy notes. [1]

1 As this whole scene is taken from fact, I subjoin the notes whose modulation is so simple, and whose effect was so profound.

|

“A few days after this final meeting, Elinor wrote to her aunt in York to announce, that if she still lived, and was not unwilling to admit her, she would reside with her for life; and she could not help intimating, that her life would probably not outlast that of her hostess. She did not tell what the widow Sandal had whispered to her at her first arrival at the Castle, and what she now ventured to repeat with a tone that struggled between the imperative and the persuasive,—the conciliating and the intimidative. Elinor yielded,—and the indelicacy of this representation, had only the effect to make her shrink from its repetition.

“On her departure, Margaret wept, and Sandal shewed as much tender officiousness about her journey, as if it were to terminate in their renewed bridal. To escape from this, Elinor hastened her preparations for departure.

“When she arrived at a certain distance from the Castle, she dismissed the family carriage, and said she would go on foot with her female servant to the farmhouse where horses were awaiting her. She went there, but remained concealed, for the report of the approaching bridal resounded in her ears.* * * *

* * * *

“The day arrived—Elinor rose very early—the bells rung out a merry peal—(as she had once heard them do on another occasion)—the troops of friends arrived in greater numbers, and with equal gaiety as they had once assembled to escort her—she saw their equipages gleaming along—she heard the joyous shouts of half the county—she imagined to herself the timid smile of Margaret, and the irradiated countenance of him who had been her bridegroom.

“Suddenly there was a pause. She felt that the ceremony was going on—was finished—that the irrevocable words were spoken—the indissoluble tie was knit! Again the shout and wild joyance burst forth as the sumptuous cavalcade returned to the Castle. The glare of the equipages,—the splendid habits of the riders,—the cheerful groupe of shouting tenantry,—she saw it all!* * * *

* * * *

“When all was over, Elinor glanced accidentally at her dress—it was white like her bridal habit;—shuddering she exchanged it for a mourning habit, and set out, as she hoped, on her last journey.

CHAPTER XXXII

Fuimus, non sumus.

“When Elinor arrived in Yorkshire, she found her aunt was dead. Elinor went to visit her grave. It was, in compliance with her last request, placed near the window of the independent meetinghouse, and bore for inscription her favourite text, “Those whom he foreknew, he also predestinated,” &c. &c. Elinor stood by the grave some time, but could not shed a tear. This contrast of a life so rigid, and a death so hopeful,—this silence of humanity, and eloquence of the grave,—pierced through her heart, as it will through every heart that has indulged in the inebriation of human passion, and feels that the draught has been drawn from broken cisterns.

“Her aunt’s death made Elinor’s life, if possible, more secluded, and her habits more monotonous than they would otherwise have been. She was very charitable to the cottagers in her neighbourhood; but except to visit their habitations, she never quitted her own.* * * *

* * * *

“Often she contemplated a small stream that flowed at the end of her garden. As she had lost all her sensibility of nature, another motive was assigned for this mute and dark contemplation; and her servant, much attached to her, watched her closely.* * * *

* * * *

“She was roused from this fearful state of stupefaction and despair, which those who have felt shudder at the attempt to describe, by a letter from Margaret. She had received several from her which lay unanswered, (no unusual thing in those days), but this she tore open, read with interest inconceivable, and prepared instantly to answer by action.

“Margaret’s high spirits seemed to have sunk in her hour of danger. She hinted that that hour was rapidly approaching, and that she earnestly implored the presence of her affectionate kinswoman to soothe and sustain in the moment of her approaching peril. She added, that the manly and affectionate tenderness of John Sandal at this period, had touched her heart more deeply, if possible, than all the former testimonies of his affection—but that she could not bear his resignation of all his usual habits of rural amusement, and of the neighbouring society—that she in vain had chided him from her couch, where she lingered in pain and hope, and hoped that Elinor’s presence might induce him to yield to her request, as he must feel, on her arrival, the dearest companion of her youth was present—and that, at such a moment, a female companion was more suitable than even the gentlest and most affectionate of the other sex.* * * *

* * * *

“Elinor set out directly. The purity of her feelings had formed an impenetrable barrier between her heart and its object,—and she apprehended no more danger from the presence of one who was wedded, and wedded to her relative, than from that of her own brother.

“She arrived at the Castle—Margaret’s hour of danger had begun—she had been very ill during the preceding period. The natural consequences of her situation had been aggravated by a feeling of dignified responsibility on the birth of an heir to the house of Mortimer—and this feeling had not contributed to render that situation more supportable.

“Elinor bent over the bed of pain—pressed her cold lips to the burning lips of the sufferer—and prayed for her.

“The first medical assistance in the country (then very rarely employed on such occasions) had been obtained at a vast expence. The widow Sandal, declining all attendance on the sufferer, paced through the adjacent apartments in agony unutterable and unuttered.

“Two days and nights went on in hope and terror—the bell-ringers sat up in every church within ten miles round—the tenantry crowded round the Castle with honest heartfelt solicitude—the neighbouring nobility sent their messages of inquiry every hour. An accouchement in a noble family was then an event of importance.

“The hour came—twins were born dead—and the young mother was fated to follow them within a few hours! While life yet remained, Margaret shewed the remains of the lofty spirit of the Mortimers. She sought with her cold hand that of her wretched husband and of the weeping Elinor. She joined them in an embrace which one of them at least understood, and prayed that their union might be eternal. She then begged to see the bodies of her infant sons—they were produced; and it was said that she uttered expressions, intimating that, had they not been the heirs of the Mortimer family—had not expectation been wound so high, and supported by all the hopes that life and youth could flatter her with,—she and they might yet have existed.

“As she spoke, her voice grew feebler, and her eyes dim—their last light was turned on him she loved; and when sight was gone, she still felt his arms enfold her. The next moment they enfolded—nothing!

“In the terrible spasms of masculine agony—the more intensely felt as they are more rarely indulged—the young widower dashed himself on the bed, which shook with his convulsive grief; and Elinor, losing all sense but that of a calamity so sudden and so terrible, echoed his deep and suffocating sobs, as it she whom they deplored had not been the only obstacle to her happiness.* * * *

* * * *

“Amid the voice of mourning that rung through the Castle from vault to tower in that day of trouble, none was loud like that of the widow Sandal—her wailings were shrieks, her grief was despair. Rushing through the rooms like one distracted, she tore her hair out by the roots, and imprecated the most fearful curses on her head. At length she approached the apartment where the corse lay. The servants, shocked at her distraction, would have withheld her from entering it, but could not. She burst into the room, cast one wild look on its inmates—the still corse and the dumb mourners—and then, flinging herself on her knees before her son, confessed the secret of her guilt, and developed to its foul base the foundation of that pile of iniquity and sorrow which had now reached its summit.

“Her son listened to this horrible confession with fixed eye and features unmoved; and at its conclusion, when the wretched penitent implored the assistance of her son to raise her from her knees, he repelled her outstretched hands, and with a weak wild laugh, sunk back on the bed. He never could be removed from it till the corse to which he clung was borne away, and then the mourners hardly knew which to deplore—her who was deprived of the light of life, or him in whom the light of reason was extinguished for ever!* * * *

* * * *

“The wretched, guilty mother, (but for her fate no one can be solicitous), a few months after, on her dying bed, declared the secret of her crime to a minister of an independent congregation, who was induced, by the report of her despair, to visit her. She confessed that, being instigated by avarice, and still more by the desire of regaining her lost consequence in the family, and knowing the wealth and dignity her son would acquire, and in which she must participate, by his marriage with Margaret, she had, after using all the means of persuasion and intreaty, been driven, in despair at her disappointment, to fabricate a tale as false as it was horrible, which she related to her deluded son on the evening before his intended nuptials with Elinor. She had assured him he was not her son, but the offspring of the illicit commerce of her husband the preacher with the Puritan mother of Elinor, who had formerly been one of his congregation, and whose well-known and strongly-expressed admiration of his preaching had been once supposed extended to his person,—had caused her much jealous anxiety in the early years of their marriage, and was now made the basis of this horrible fiction. She added, that Margaret’s obvious attachment to her cousin had, in some degree, palliated her guilt to herself; but that, when she saw him quit her house in despair on the morning of his intended marriage, and rush he knew not whither, she was half tempted to recall him, and confess the truth. Her mind again became hardened, and she reflected that her secret was safe, as she had bound him by an oath, from respect to his father’s memory, and compassion to the guilty mother of Elinor, never to disclose the truth to her daughter.

“The event had succeeded to her guilty wishes.—Sandal beheld Elinor with the eyes of a brother, and the image of Margaret easily found a place in his unoccupied affections. But, as often befals to the dealers in falsehood and obliquity, the apparent accomplishment of her hopes proved her ruin. In the event of the marriage of John and Margaret proving issueless, the estates and title went to the distant relative named in the will; and her son, deprived of reason by the calamities in which her arts had involved him, was by them also deprived of the wealth and rank to which they were meant to raise him, and reduced to the small pension obtained by his former services,—the poverty of the King, then himself a pensioner of Lewis XIV., forbidding the possibility of added remuneration. When the minister heard to the last the terrible confession of the dying penitent, in the awful language ascribed to Bishop Burnet when consulted by another criminal,—he bid her “almost despair,” and departed.* * * *

* * * *

“Elinor has retired, with the helpless object of her unfading love and unceasing care, to her cottage in Yorkshire. There, in the language of that divine and blind old man, the fame of whose poetry has not yet reached this country, it is

“Her delight to see him sitting in the house,”

and watch, like the father of the Jewish champion, the growth of that “God-given strength,” that intellectual power, which, unlike Samson’s, will never return.

“After an interval of two years, during which she had expended a large part of the capital of her fortune in obtaining the first medical advice for the patient, and “suffered many things of many physicians,” she gave up all hope,—and, reflecting that the interest of her fortune thus diminished would be but sufficient to procure the comforts of life for herself and him whom she has resolved never to forsake, she sat down in patient misery with her melancholy companion, and added one more to the many proofs of woman’s heart, “unwearied in well-doing,” without the intoxication of passion, the excitement of applause, or even the gratitude of the unconscious object.

“Were this a life of calm privation, and pulseless apathy, her efforts would scarce have merit, and her sufferings hardly demand compassion; but it is one of pain incessant and immitigable. The first-born of her heart lies dead within it; but that heart is still alive with all its keenest sensibilities, its most vivid hopes, and its most exquisite sense of grief.* * * *

* * * *

“She sits beside him all day—she watches that eye whose light was life, and sees it fixed on her in glassy and unmeaning complacency—she dreams of that smile which burst on her soul like the morning sun over a landscape in spring, and sees that smile of vacancy which tries to convey satisfaction, but cannot give it the language of expression. Averting her head, she thinks of other days. A vision passes before her.—Lovely and glorious things, the hues of whose colouring are not of this world, and whose web is too fine to be woven in the loom of life,—rise to her eye like the illusions of enchantment. A strain of rich remembered music floats in her hearing—she dreams of the hero, the lover, the beloved,—him in whom were united all that could dazzle the eye, inebriate the imagination, and melt the heart. She sees him as he first appeared to her,—and the mirage of the desert present not a vision more delicious and deceptive—she bends to drink of that false fountain, and the stream disappears—she starts from her reverie, and hears the weak laugh of the sufferer, as he moves a little water in a shell, and imagines he sees the ocean in a storm!* * * *

* * * *

“She has one consolation. When a short interval of recollection returns,—when his speech becomes articulate,—he utters her name, not that of Margaret, and a beam of early hope dances on her heart as she hears it, but fades away as fast as the rare and wandering ray of intellect from the lost mind of the sufferer!* * * *

* * * *

“Unceasingly attentive to his health and his comforts, she walked out with him every evening, but led him through the most sequestered paths, to avoid those whose mockful persecution, or whose vacant pity, might be equally torturing to her feelings, or harassing to her still gentle and smiling companion.

“It was at this period,” said the stranger to Aliaga, “I first became acquainted with—I mean—at this time a stranger, who had taken up his abode near the hamlet where Elinor resided, was seen to watch the two figures as they passed slowly on their retired walk. Evening after evening he watched them. He knew the history of these two unhappy beings, and prepared himself to take advantage of it. It was impossible, considering their secluded mode of existence, to obtain an introduction. He tried to recommend himself by his occasional attentions to the invalid—he sometimes picked up the flowers that an unconscious hand flung into the stream, and listened, with a gracious smile, to the indistinct sounds in which the sufferer, who still retained all the graciousness of his perished mind, attempted to thank him.

“Elinor felt grateful for these occasional attentions; but she was somewhat alarmed at the assiduity with which the stranger attended their melancholy walk every evening,—and, whether encouraged, neglected, or even repelled, still found the means of insinuating himself into companionship. Even the mournful dignity of Elinor’s demeanour,—her deep dejection,—her bows or brief replies,—were unavailing against the gentle but indefatigable importunity of the intruder.

“By degrees he ventured to speak to her of her misfortunes,—and that topic is a sure key to the confidence of the unhappy. Elinor began to listen to him;—and, though somewhat amazed at the knowledge he displayed of every circumstance of her life, she could not but feel soothed by the tone of sympathy in which he spoke, and excited by the mysterious hints of hope which he sometimes suffered to escape him as if involuntarily. It was observed soon by the inmates of the hamlet, whom idleness and the want of any object of excitement had made curious, that Elinor and the stranger were inseparable in their evening walks.* * * *

* * * *

“It was about a fortnight after this observation was first made, that Elinor, unattended, drenched with rain, and her head uncovered, loudly and eagerly demanded admittance, at a late hour, at the house of a neighbouring clergyman. She was admitted,—and the surprise of her reverend host at this visit, equally unseasonable and unexpected, was exchanged for a deeper feeling of wonder and terror as she related the cause of it. He at first imagined (knowing her unhappy situation) that the constant presence of an insane person might have a contagious effect on the intellects of one so perseveringly exposed to that presence.

“As Elinor, however, proceeded to disclose the awful proposal, and the scarcely less awful name of the unholy intruder, the clergyman betrayed considerable emotion; and, after a long pause, desired permission to accompany her on their next meeting. This was to be the following evening, for the stranger was unremitting in his attendance on her lonely walks.

“It is necessary to mention, that this clergyman had been for some years abroad—that events had occurred to him in foreign countries, of which strange reports were spread, but on the subject of which he had been always profoundly silent—and that having but lately fixed his residence in the neighbourhood, he was equally a stranger to Elinor, and to the circumstances of her past life, and of her present situation.* * * *

* * * *

“It was now autumn,—the evenings were growing short, and the brief twilight was rapidly succeeded by night. On the dubious verge of both, the clergyman quitted his house, and went in the direction where Elinor told him she was accustomed to meet the stranger.

“They were there before him; and in the shuddering and averted form of Elinor, and the stern but calm importunity of her companion, he read the terrible secret of their conference. Suddenly he advanced and stood before the stranger. They immediately recognised each other. An expression that was never before beheld there—an expression of fear—wandered over the features of the stranger! He paused for a moment, and then departed without uttering a word—nor was Elinor ever again molested by his presence.* * * *

* * * *

“It was some days before the clergyman recovered from the shock of this singular encounter sufficiently to see Elinor, and explain to her the cause of his deep and painful agitation.

“He sent to announce to her when he was able to receive her, and appointed the night for the time of meeting, for he knew that during the day she never forsook the helpless object of her unalienated heart. The night arrived—imagine them seated in the antique study of the clergyman, whose shelves were filled with the ponderous volumes of ancient learning—the embers of a peat fire shed a dim and fitful light through the room, and the single candle that burned on a distant oaken stand, seemed to shed its light on that alone—not a ray fell on the figures of Elinor and her companion, as they sat in their massive chairs of carved-like figures in the richly-wrought nitches of some Catholic place of worship—“

“That is a most profane and abominable comparison,” said Aliaga, starting from the doze in which he had frequently indulged during this long narrative.

“But hear the result,” said the pertinacious narrator. “The clergyman confessed to Elinor that he had been acquainted with an Irishman of the name of Melmoth, whose various erudition, profound intellect, and intense appetency for information, had interested him so deeply as to lead to a perfect intimacy between them. At the breaking out of the troubles in England, the clergyman had been compelled, with his father’s family, to seek refuge in Holland. There again he met Melmoth, who proposed to him a journey to Poland—the offer was accepted, and to Poland they went. The clergyman here told many extraordinary tales of Dr Dee, and of Albert Alasco, the Polish adventurer, who were their companions both in England and Poland—and he added, that he felt his companion Melmoth was irrevocably attached to the study of that art which is held in just abomination by all “who name the name of Christ.” The power of the intellectual vessel was too great for the narrow seas where it was coasting—it longed to set out on a voyage of discovery—in other words, Melmoth attached himself to those impostors, or worse, who promised him the knowledge and the power of the future world—on conditions that are unutterable.” A strange expression crossed his face as he spoke. He recovered himself, and added, “From that hour our intercourse ceased. I conceived of him as of one given up to diabolical delusions—to the power of the enemy.

“I had not seen Melmoth for some years. I was preparing to quit Germany, when, on the eve of my departure, I received a message from a person who announced himself as my friend, and who, believing himself dying, wished for the attendance of a Protestant minister. We were then in the territories of a Catholic electoral bishop. I lost no time in attending the sick person. As I entered his room, conducted by a servant, who immediately closed the door and retired, I was astonished to see the room filled with an astrological apparatus, books and implements of a science I did not understand; in a corner there was a bed, near which there was neither priest or physician, relative or friend—on it lay extended the form of Melmoth. I approached, and attempted to address to him some words of consolation. He waved his hand to me to be silent—and I was so. The recollection of his former habits and pursuits, and the view of his present situation, had an effect that appalled more than it amazed me. “Come near,” said Melmoth, speaking very faintly—“nearer. I am dying—how my life has been passed you know but too well. Mine was the great angelic sin—pride and intellectual glorying! It was the first mortal sin—a boundless aspiration after forbidden knowledge! I am now dying. I ask for no forms of religion—I wish not to hear words that have to me no meaning, or that I wish had none! Spare your look of horror. I sent for you to exact your solemn promise that you will conceal from every human being the fact of my death—let no man know that I died, or when, or where.”

“He spoke with a distinctness of tone, and energy of manner, that convinced me he could not be in the state he described himself to be, and I said, “But I cannot believe you are dying—your intellects are clear, your voice is strong, your language is coherent, and but for the paleness of your face, and your lying extended on that bed, I could not even imagine you were ill.” He answered, “Have you patience and courage to abide by the proof that what I say is true?” I replied, that I doubtless had patience, and for the courage, I looked to that Being for whose name I had too much reverence to utter in his hearing. He acknowledged my forbearance by a ghastly smile which I understood too well, and pointed to a clock that stood at the foot of his bed. “Observe,” said he, “the hour-hand is on eleven, and I am now sane, clear of speech, and apparently healthful—tarry but an hour, and you yourself will behold me dead!”

“I remained by his bed-side—the eyes of both were fixed intently on the slow motion of the clock. From time to time he spoke, but his strength now appeared obviously declining. He repeatedly urged on me the necessity of profound secresy, its importance to myself, and yet he hinted at the possibility of our future meeting, I asked why he thought proper to confide to me a secret whose divulgement was so perilous, and which might have been so easily concealed? Unknowing whether he existed, or where, I must have been equally ignorant of the mode and place of his death. To this he returned no answer. As the hand of the clock approached the hour of twelve, his countenance changed—his eyes became dim—his speech inarticulate—his jaw dropped—his respiration ceased. I applied a glass to his lips—but there was not a breath to stain it. I felt his wrist but there was no pulse. I placed my hand on his heart—there was not the slightest vibration. In a few minutes the body was perfectly cold. I did not quit the room till nearly an hour after the body gave no signs of returning animation.

“Unhappy circumstances detained me long abroad. I was in various parts of the Continent, and every where I was haunted with the report of Melmoth being still alive. To these reports I gave no credit, and returned to England in the full conviction of his being dead. Yet it was Melmoth who walked and spoke with you the last night of our meeting. My eyes never more faithfully attested the presence of living being. It was Melmoth himself, such as I beheld him many years ago, when my hairs were dark and my steps were firm. I am changed, but he is the same—time seems to have forborne to touch him from terror. By what means or power he is thus enabled to continue his posthumous and preternatural existence, it is impossible to conceive, unless the fearful report that every where followed his steps on the Continent, be indeed true.”

“Elinor, impelled by terror and wild curiosity, inquired into that report which dreadful experience had anticipated the meaning of. “Seek no farther,” said the minister, “you know already more than should ever have reached the human ear, or entered into the conception of the human mind. Enough that you have been enabled by Divine Power to repel the assaults of the evil one—the trial was terrible, but the result will be glorious. Should the foe persevere in his attempts, remember that he has been already repelled amid the horrors of the dungeon and of the scaffold, the screams of Bedlam and the flames of the Inquisition—he is yet to be subdued by a foe that he deemed of all others the least invincible—the withered energies of a broken heart. He has traversed the earth in search of victims, “Seeking whom he might devour,”—and has found no prey, even where he might seek for it with all the cupidity of infernal expectation. Let it be your glory and crown of rejoicing, that even the feeblest of his adversaries has repulsed him with a power that will always annihilate his.”* * * *

* * * *

“Who is that faded form that supports with difficulty an emaciated invalid, and seems at every step to need the support she gives?—It is still Elinor tending John. Their path is the same, but the season is changed—and that change seems to her to have passed alike on the mental and physical world. It is a dreary evening in Autumn—the stream flows dark and turbid beside their path—the blast is groaning among the trees, and the dry discoloured leaves are sounding under their feet—their walk is uncheered by human converse, for one of them no longer thinks, and seldom speaks!

“Suddenly he gives a sign that he wishes to be seated—it is complied with, and she sits beside him on the felled trunk of a tree. He declines his head on her bosom, and she feels with delighted amazement, a few tears streaming on it for the first time for years—a soft but conscious pressure of her hand, seems to her like the signal of reviving intelligence—with breathless hope she watches him as he slowly raises his head, and fixes his eyes—God of all consolation, there is intelligence in his glance! He thanks her with an unutterable look for all her care, her long and painful labour of love! His lips are open, but long unaccustomed to utter human sounds, the effort is made with difficulty—again that effort is repeated and fails—his strength is exhausted—his eyes close—his last gentle sigh is breathed on the bosom of faith and love—and Elinor soon after said to those who surrounded her bed, that she died happy, since he knew her once more! She gave one parting awful sign to the minister, which was understood and answered!

CHAPTER XXXIII

Cum mihi non tantum furesque feræque suëtæ,

Hunc vexare locum, curæ sunt atque labori;

Quantum carminibus quæ versant atque venenis,

Humanos animos.HORACE

“It is inconceivable to me,” said Don Aliaga to himself, as he pursued his journey the next day—“it is inconceivable to me how this person forces himself on my company, harasses me with tales that have no more application to me than the legend of the Cid, and may be as apocryphal as the ballad of Roncesvalles—and now he has ridden by my side all day, and, as if to make amends for his former uninvited and unwelcome communicativeness, he has never once opened his lips.”

“Senhor,” said the stranger, then speaking for the first time, as if he read Aliaga’s thoughts—“I acknowledge myself in error for relating to you a narrative in which you must have felt there was little to interest you. Permit me to atone for it, by recounting to you a very brief one, in which I flatter myself you will be disposed to feel a very peculiar interest.”—“You assure me it will be brief,” said Aliaga. “Not only so, but the last I shall obtrude on your patience,” replied the stranger. “On that condition,” said Aliaga, “in God’s name, brother, proceed. And look you handle the matter discreetly, as you have said.”

“There was,” said the stranger, “a certain Spanish merchant, who set out prosperously in business; but, after a few years, finding his affairs assume an unfavourable aspect, and being tempted by an offer of partnership with a relative who was settled in the East Indies, had embarked for those countries with his wife and son, leaving behind him an infant daughter in Spain.”—“That was exactly my case,” said Aliaga, wholly unsuspicious of the tendency of this tale.

“Two years of successful occupation restored him to opulence, and to the hope of vast and future accumulation. Thus encouraged, our Spanish merchant entertained ideas of settling in the East Indies, and sent over for his young daughter with her nurse, who embarked for the East Indies with the first opportunity, which was then very rare.”—“This reminds me exactly of what occurred to myself,” said Aliaga, whose faculties were somewhat obtuse.

“The nurse and infant were supposed to have perished in a storm which wrecked the vessel on an isle near the mouth of a river, and in which the crew and passengers perished. It was said that the nurse and child alone escaped; that by some extraordinary chance they arrived at this isle, where the nurse died from fatigue and want of nourishment, and the child survived, and grew up a wild and beautiful daughter of nature, feeding on fruits,—and sleeping amid roses,—and drinking the pure element,—and inhaling the harmonies of heaven,—and repeating to herself the few Christian words her nurse had taught her, in answer to the melody of the birds that sung to her, and of the stream whose waves murmured in accordance to the pure and holy music of her unearthly heart.”—“I never heard a word of this before,” muttered Aliaga to himself. The stranger went on.

“It was said that some vessel in distress arrived at the isle,—that the captain had rescued this lovely lonely being from the brutality of the sailors,—and, discovering from some remains of the Spanish tongue which she still spoke, and which he supposed must have been cultivated during the visits of some other wanderer to the isle, he undertook, like a man of honour, to conduct her to her parents, whose names she could tell, though not their residence, so acute and tenacious is the memory of infancy. He fulfilled his promise, and the pure and innocent being was restored to her family, who were then residing in the city of Benares.” Aliaga, at these words, stared with a look of intelligence somewhat ghastly. He could not interrupt the stranger—he drew in his breath, and closed his teeth.

“I have since heard,” said the stranger, “that the family has returned to Spain,—that the beautiful inhabitant of the foreign isle is become the idol of your cavaliers of Madrid,—your loungers of the Prado,—your sacravienses,—your—by what other name of contempt shall I call them? But listen to me,—there is an eye fixed on her, and its fascination is more deadly than that fabled of the snake!—There is an arm extended to seize her, in whose grasp humanity withers!—That arm even now relaxes for a moment,—its fibres thrill with pity and horror,—it releases the victim for a moment,—it even beckons her father to her aid!—Don Francisco, do you understand me now?—Has this tale interest or application for you?”

“He paused, but Aliaga, chilled with horror, was unable to answer him but by a feeble exclamation. “If it has,” resumed the stranger, “lose not a moment to save your daughter!” and, clapping spurs to his mule, he disappeared through a narrow passage among the rocks, apparently never intended to be trod by earthly traveller. Aliaga was not a man susceptible of strong impressions from nature; but, if he had been, the scene amid which this mysterious warning was uttered would have powerfully ministered to its effect. The time was evening,—a grey and misty twilight hung over every object;—the way lay through a rocky road, that wound among mountains, or rather stony hills, bleak and bare as those which the weary traveller through the western isle1 sees rising amid the moors, to which they form a contrast without giving a relief. Heavy rains had made deep gullies amid the hills, and here and there a mountain-stream brawled amid its stony channel, like a proud and noisy upstart, while the vast chasms that had been the beds of torrents which once swept through them in thunder, now stood gaping and ghastly like the deserted abodes of ruined nobility. Not a sound broke on the stillness, except the monotonous echo of the hoofs of the mules answered from the hollows of the hill, and the screams of the birds, which, after a few short circles in the damp and cloudy air, fled back to their retreats amid the cliffs. * * * *

1 Ireland,—forsan.

* * * *

“It is almost incredible, that after this warning, enforced as it was by the perfect acquaintance which the stranger displayed of Aliaga’s former life and family-circumstances, it should not have had the effect of making him hurry homewards immediately, particularly as it seems he thought it of sufficient importance to make it the subject of correspondence with his wife. So it was however.

“At the moment of the stranger’s departure, it was his resolution not to lose a moment in hastening homewards; but at the next stage he arrived at, there were letters of business awaiting him. A mercantile correspondent gave him the information of the probable failure of a house in a distant part of Spain, where his speedy presence might be of vital consequence. There were also letters from Montilla, his intended son-in-law, informing him that the state of his father’s health was so precarious, it was impossible to leave him till his fate was decided. As the decisions of fate involved equally the wealth of the son, and the life of the father, Aliaga could not help thinking there was as much prudence as affection in this resolution.

“After reading these letters, Aliaga’s mind began to flow in its usual channel. There is no breaking through the inveterate habitudes of a thorough-paced mercantile mind, “though one rose from the dead.” Besides, by this time the mysterious image of the stranger’s presence and communications were fading fast from a mind not at all habituated to visionary impressions. He shook off the terrors of this visitation by the aid of time, and gave his courage the credit due to that aid. Thus we all deal with the illusions of the imagination,—with this difference only, that the impassioned recal them with the tear of regret, and the unimaginative with the blush of shame. Aliaga set out for the distant part of Spain where his presence was to save this tottering house in which he had an extensive concern, and wrote to Donna Clara, that it might be some months before he returned to the neighbourhood of Madrid.

[ End of Chapter XXXIII ]

| [ previous ] | [ next ] |