Life

| b. 12 Nov. 1934, in Dublin; grew up in Knockanroe [townland], nr. Ballinamore, Co Leitrim; eldest of seven children (5 girls, 2 boys); son of Francis [Frank] McGahern, a Garda [police] sargeant and former commandant in the IRA; brought up at Aughawillan, nr. Ballinamore, with his mother Susan [née MacMahon], a primary school-teacher, and latterly on a small farm bought before her early death from cancer in his tenth year - providing the material for his first novel (The Barracks, 1963); removed before her death to the Garda Barracks at Cootehall by his father, who was station-sergeant there, and forbidden to attend her funeral; ed. Presentation College [Secondary School], in Carrick-on-Shannon, where he was identified as a gifted student and briefly considered becoming a priest; befriended by the Moroneys, owners of Woodbrook - the ‘big house’ formerly belonging to the Anglo-Irish Kirkwood family, who gave him access to their library (‘I certainly would never have been a writer except I got access to that 19th-century library’); suffered much physical [?and some degree of sexual] abuse at the hands of his father, later related in The Dark; | ||||||

| entered St. Patrick’s Training College, Drumcondra, on County Scholarship, 1952-54, and later at studied at UCD, 1957; spent first summer as a labourer on building sites in London, living in a Catholic hostel in Whitechapel (‘land of Shakespeare and Wordsworth ... like stepping on sacred soil’); first taught at Athboy, later at Drogheda, commuting to Dublin for the cultural life there; his literary interested widened through friendship with James [Jimmy] and Patrick Swift, and through acquaintance with Patrick Kavanagh and other Dublin literati; appt. to junior teach classes at St. John the Baptist’s National School [Scoil Eoin Báiste, var. Bhaiste, Gl. gen.] - otherwise Belgrove School, Clontarf, Co. Dublin, 1958-65; (‘seven years’); lived at 57 Howth Rd., Clontarf; contrib. extract of a novel as “The End or Beginning of Love” to X, a lit. journal ed. by Patrick Swift and David Wright - on advice of his friend Jimmy Swift, in turn a close friend of John Jordan since Synge St. CBS; his novel of that title was seen by Peter de Sautoy at Faber who invited him to an interview in London and agreed to a contract (£75 down and £75 on delivery) of a rewritten version at JMG’s insistence; afterwards asked by Charles Monteith, a senior director of Faber and his first editor [see infra] to submit the MS for “AE” [George Russell] Memorial Award of the Irish Arts Council, which he won, 1962; | ||||||

| wrote admiringly to Michael McLaverty, and continued to correspond with him, from Jan. 1959; introduced to Seamus Heaney - then teaching at St. Thomas’s - by MacLaverty, 1963; read his story “Coming into His Kingdom” in Newman House, 1962; submitted it to the New Yorker and suffered rejection; afterwards published it in the Kilkenny Magazine; contrib. “A Barrack Evening”, an extract from a novel, to Dolmen Miscellany of Irish Writing (Autumn 1962); his novel The Barracks (1963) issued by Faber; modelled on the death of his own mother, it concerns the approaching death of Elizabeth Regan, a police sergeant’s wife modelled on his own mother, from cancer; the book secured McGahern acquired a reputation for uncompromising realism; McGahern wins a Macaulay Fellowship worth £1,000 and spent a year living outside Ireland on a sabbatical from teaching, 1964; | ||||||

| issued The Dark (1965), dealing with the Roscommon childhood of a scholarship boy in the power of an abusive father (Mahoney) and a series of tyrannical and abusive priests; banned by the Irish Censorship Board, June 1965; dismissed from his teaching post without explanation, though actually on account of his relationship with Annikki Laaksi, a Finnish theatrical producer and divorcée - purportedly at behest of Archbishop J. C. McQuaid (Dublin diocese), 1965 - circumstances partially portrayed in The Leavetaking; defended by Owen Sheehy-Skeffington, who questioned the original banning order [as infra]; Samuel Beckett offered support which was kindly declined by the writer, who preferred to remain silent; interviewed by Gay Byrne on the Late Late Show from King’s Hall, Belfast and refused to condemn the Church (‘the weather of my early life’); settled in London and m. Laaksi, 1965, but rarely together due to their respective attachment to Ireland and Finland; | ||||||

|

||||||

| worked as a part-time school-teacher but also on building sites, 1965-68; ceased teaching, 1966; appt. Research Fellow at University of Reading, 1968; travelled to teach as visiting professor at Colgate University, NY, 1969; The Barracks successfully adapted by Hugh Leonard for the Dublin Theatre Festival, premiered 6 Oct. 1969 at the Olympia Th.; living in Paris with Madeline Green, childhood friend of his New York editor, June 1970 [see extant invitation to Patrick Swift and his partner written at Rue Christine, Paris 6]; issued Nightlines (1970), stories; wrote The Power of Darkness, after Tolstoy’s play, rejected by the Abbey Th., 28 Sept. 1972, but produced as radio script by Denys Hawthorne (BBC Radio 3, 15 Oct. 1972); divorced Laaksi and m. Green, 1973; returned to Ireland, 1972, at first to Galway, and then to lakeside farm at Foxfield between Ballinamore at Fenagh, nr. Mohill, Co. Leitrim, 1974 (‘My eldest son has bought a snipe run in behind the Ivy Leaf Ballroom’, said his father); | ||||||

| appt. writer-in-residence, Durham University, and afterwards at Newcastle University; Victoria (Canada) and University College Dublin; issued The Leavetaking (1974), concerning Patrick Moran’s disillusion with Irish school-teaching and his departure for London, with an American, Isobel, with whom he shares comparable parental relationships, respectively with the mother and the father; reissued in revised version, 1984; issued Getting Through (1978), stories; issued The Pornographer (1979), a novel, later revised; winner Irish-American Foundation Award, 1985; issued High Ground (1985), stories; wrote The Rockingham Shoot (1987), a radio play, for BBC - and was black-listed by An Phoblacht as British sympathiser; awarded Chevalier des Arts et Lettres, 1989; | ||||||

| issued Amongst Women (1990), a ‘small-house novel’ - acc. Antoinette Quinn - commenced as a story “Young and Old” and continued as a novel, The Morans, to be changed to the present title in the publisher’s galley; concerning Moran, an independence-fighter, living out his last days with his second wife and three daughters being the story of the later family life of a politically-disappointed former Republican soldier, dominating his children in his small-farm home on the Roscommon-Leitrim border - later filmed; nominated ofr Booker Award; winner of Irish Times/Aer Lingus Literature Award (Fiction), and short-listed for the Booker Prize, 1990, writer in residence at TCD, 1988-89, with rooms in No. 25 (Rubrics), where he was ‘very happy’; wrote The Power of Darkness, dir. Gary Hynes of Druid (Abbey Th., 16 Oct. 1991), after Tolstoy’s Resurrection; appt. full Professor at Colgate University, 1991; awarded hon. D.Litt from Trinity College, Dublin, 1991; | ||||||

| his novel The Pornographer goes through several drafts as BBC film-script, with Barry Hanson [‘we tried to get rid of the pornography and it couldn’t be got rid of’]: JMcG.); issued Collected Stories (1992), readings from which were transmitted on BBC3 (19 & 20 Oct. 1992); an RTÉ profile documentary appeared in 1990; Hon. D.litt., TCD, 1991; undergoes prostate operation, 1992; sometime winner of PEN award for life-time achievement; appointed to staff of Dublin City University (DCU), in 2001; That They May Face the Rising Sun (2001), shortlisted for IMPAC Award; subject of documentary by Pat Collins (RTE, Jan. 2005); issued Memoir (April 2005), shaped by a remembered, and then imagined, experience of walking to Ollerton’s farm with his mother, but centrally featuring his father - whom he would have ‘killed’ if he had not left home; | ||||||

| d., of cancer, at the Mater Hospital, Dublin, 30 March 2006; subject of tribute by President Mary McAleese commending his ‘immense contribution to our self-understanding as a people’; he is buried in Aughawillan, besie his mother; Creatures of the Earth: New and Selected Short Stories (2006), is a final selection by the author; his essays have been edited posthumously by Stanley van der Ziel as Love of the World (2010); an annual John McGahern International Seminar was established at NUI Galway in conjunction with the Leitrim County Council in 2007; a John McGahern Yearbook was first published in 2008; his extensive papers are held at the James Hardiman Library, NUI Galway; his letters to Michael McLaverty are preserved in the collection in the Linenhall Library, Belfast. DIW DIL FDA OCIL | ||||||

Hardiman Collection (UCG): 32 boxes of materials, chiefly drafts of novels and related contents, produced c.1958-2004. The initial corpus was donated to the University by John McGahern at an official ceremony on 6 Oct. 2003 and further material added by Madeline in September 2006; papers accession June 2007 and further papers in 2009. - as online].McGahern Conferences in 2013 ...

|

||||||

|

||||||

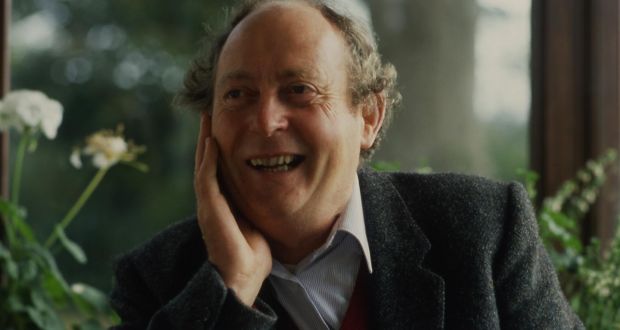

| [ See also pencil portrait of John McGahern by Patrick Swift under Works - infra. ] | ||||||

[ top ]

Works

See separate file, infra.

Criticism

See under Works, infra.

Commentary

See separate file, infra.

Quotations

See separate file, infra.

[ top ]

References

Peter Fallon & Seán Golden, ed., Soft Day: A Miscellany of Contemporary Irish Writing (Notre Dame/Wolfhound 1980), contains ‘Along the Edges’.

Grattan Freyer, Modern Irish Writing (Irish Humanities Centre 1979), contains “Korea”, from Nightlines (1970), with the introductory remark: ‘his vision is sombre in the extreme, reflecting a yearning despair and disillusion, a not uncommon mode in latter-day Ireland’.

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 3, selects extract from Nightlines and “Korea“; notes at 676 [ed. J. W. Foster, pp.938, 940, 942]; BIOG p.1135.

Hibernia Catalogue (No. 19), lists “The Creamery Manager”, in Krino, 4 (1987); The Power of Darkness: A Play (Faber 1991).

[ top ]

Notes

The Barracks (1963), concerns the death from breast cancer of Elizabeth Regan, a police sergeant’s wife - who treats her ‘as if he had married a housekeeper’ - finding herself an ‘outsider’ in the village, where she refused to join the Legion of Mary, having previously lived in wartime London where she had an affair a staff doctor, Michael Halliday, who has embraced the philosophical nihilism against which her own emergent attitudes in the face of death are a spiritual counterpoint wrestled from despairing circumstances. The novel begins and ends with a ceremonial lighting of the lamp and is roughly based on the life and death of McGahern’s own mother.

The Dark (1965), set in his native Roscommon and dealing with the experience of the unnamed narrator [young Mahoney] as a boy educated by priests and exposed to clerical tyranny as well as to the brutality and frustration of his own father, finally throwing up his scholarship to work as a lowly ESB clerk in Dublin; contains the first explicit scenes of masturbation in Irish fiction; uses alternate passages in the first and second persons (and occasionally first); written during leave of absence from teaching on Clontarg; banned by the Censorship Board, 1965.

Note: The Dark may be named after the letter received by McGahern from his father in response to the publication of The Barracks: “An old police sergeant is sitting here in the dark and waiting until the lamp flickers or at least shows light. Love, Daddy.” (See Interview, in Journal of the Short Story in English, Autumn 2003 - as attached > “dark”.)

[ top ]

The Leavetaking (1974): Patrick, and Irish school-teacher becomes involved in a painful love-affair and eventually marries Isobel, a wealthy American divorcee on moving to London after he has been dismissed from his post by Church authority; he experiences a loss of faith and puts in question his own earlier vocationalism, but resolves that the ‘small acts of love’ are themselves a sacrament to put beside those of his religion. The novel is told in the first person singular (and hence occasionally in the first person plural) and ends on a melancholy note, emphasising the fragility of relationships and the uncertainty of the future.

Getting Through [1978]: a typescript draft of the title page and contents of the collection Getting Through is held among the McGahern Papers at the Hardiman Library of Galway University (UCG/NUI) which shows a manuscript amendation making “The Beginnings of an Idea” the opening story.

Amongst Women (1990), concerning Michael Moran, an ex-guerrilla of the independence war, bewildered by the love and patience of his second wife and three daughters Rose, Sheila and Mona, in the last years of his life. Sheila has been thwarted in her desire to study medicine by her father’s opposition to the expense. Moran’s alienated elder son Luke works as a property developer in London. The sisters campaign to bring Luke back to Great Meadow, leading to an unsuccessful visit and a failure at reconcilement. The younger Michael, still a schoolboy with the Christian Brothers, is involved in an affair with Nell Monrahan, on a holiday from a working life in America, and escapes his father’s wrath by running away to England and later marries an Englishwoman, Ann Smith, whom Moran likes while Sheila marries Sean Flynn, a civil servant of whom Moran disapproves. At Moran’s funeral the local politicians walk away ‘sometimes turning their heads to look back to the crowd gathered around the grave in undisguised contempt’. The novel takes the pattern of the rosary, with its joyful, sorrowful and glorious mysteries, as a guiding structure, and to that extent the fate of Moran is a kind of crucifixion.

Media versions: Amongst Women was abridged by McGahern himself in 10 parts for BBC3 radion, and screen-written for TV by Edna Thomas (30 May 1996); also filmed as four-part series by BBC in 1998.

“The Beginning of an Idea” (in Getting Through, 1978) concerns a French woman, Eva Lindberg’s, abortive attempt to write an imaginary life of the Anton Chekhov - beginning with her notes about how the word “oysters” which was chalked on the side of the wagon that brought his body to Moscow for burial in order to preserve it from the heat.

The Power of Darkness (Faber 1991); a melodrama produced at the Abbey Theatre in 1991. Dram. persona, Peter King, a landowner, dying; Eileen, his second wife; Maggie, his 21 year-old daughter; Paul, a young workman, son of poor farmers in King’s debt for money; he is a ‘potent mixture of good looks, sexual egotism, weakness and vanity’; his mother, Baby, who regards Paul as ‘honey’ to women; her decent husband Oliver, deeply religious; an old soldier, Paddy. (From McGahern’s notes). Dedicatory thanks to Thomas Kilroy.

Korea (1995), film dir. by Cathal Black (75 mins), based on McGahern’s story; Amongst Women was filmed under direction of Tom Cairns to screenplay by Adrian Hodges, in 4-part series originating with BBC (Northern Ireland) and finished in co-production between RTÉ and the Film Board with Parallel films; shown on RTE from 19 May 1998, following discussion programme on McGahern with Declan Kiberd and others; Tom Doyle appears as Moran, with Anne Marie Duff, Geraldine O’Raw and Susan Lynch as his dgs.; 1996 winner of Asta Nielsen Best Film Award at the Copenhagen Film Festival

That They May Face the Rising Sun (2003) spans a year on the tiny Irish farm of Joe and Kate Ruttledge, incomers amid an ageing population whose best fled to England or educated themselves away from the fields; less characters than lenses through which to observe a cloistered demi-paradise; McGahern imagines a Book of Hours ornamented by the rural cycle - here are herons, otters, sloes ripening on the blackthorn and bream rolling in the lake; no sappy landscape, but almost complete in and of itself: “I’ve never, never moved from here and I know the whole world”, claims their neighbour Jamesie; during pleasurable shared silences time folds in on itself, and tales of the past seem more urgent than the present; even Jamesie’s clocks all chime at different times - when the clockmaker corrects their mechanisms, darkness presses on a community hovering between the world and the grave. (See DJ [book-notice], in The Guardian, 8 Feb. 2003.)

[ top ]

McGahern’s début (The Barracks)|

First appearance: McGahern was encouraged by his friend Jimmy Swift - being a close associate of Tom Jordan since Synge St. CBS - to send an extract of his first novel The Beginning and End of Love to Jimmy’s brother Patrick, who was editing the lit. journal X: A Quarterly Review with David Wright in London (i.e., “The End or Beginning of Love”). Second appearance: McGahern contributed “A Barrack Evening”, an extract from a novel [i.e., The Barracks, 1963], to the Dolmen Miscellany of Irish Writing (Autumn 1962) published by Liam Millar. [See details in own copy BS.] Third appearance: McGahern’s first novel was published in book-form as The Barracks (1963) after Peter de Sautoy of Faber, a director of the firm who saw his work in the X; later interviewed by Charles Monteith, acting as editor, who prompted him to submit the manuscript for the George “AE” Russell Prize - which he McGahern won.

Final publication: The MS, still entitled The End or Beginning of Love, dealing closely with the feelings of his mother as her death from cancer approaches, was accepted by Faber but then withdrawn by McGahern and rewritten - some parts only being incorporated in The Barracks (Faber & Faber 1963), which was dedicated to Jimmy Swift. |

|

[ top ]

‘In pursuit of a single flame’, review essay on ‘neglected classic of the War of Independence’ (Irish Times, 17 Feb. 1996, ‘Weekend’, p.8), concerning Ernie O’Malley’s The Singing Flame; McGahern departs from a memory of teaching in Clontarf and finding that a nephew of O’Malley was using a manuscript notebook of his uncle’s for sums: ‘a symbol of the disregard shown the writer’ [as distinct from the soldier] at that time. [See under O’Malley, infra.

(See also Hermione Lee’s assessment of McGahern’s attitude to O’Malley, in Lee, ‘A Sly Twinkle’, review-article on Love of the World: Essays, in Times Literary Supplement, 4 Dec. 2009, pp.3-5 [copy in RICORSO Library, as attached].)

Belgrove farewells: McGahern reports that a teachers’ representative told him at the time of his dismissal from Belgrave School in Clontarf: ‘If it was just the auld book, we might have been able to do something for you, but with marrying this foreign woman you had turned yourself into a hopeless case.’ (Quoted in Hugh McFadden, review of Young John McGahern, by Denis Sampson, in Books Ireland, April 2012, p.59.)

Another Regan: The dying husband in Kathleen Joyce-Prendergast’s novel This is My Land (1944) is called Regan (cf. McGahern’s Barracks).

Kerry Ingredients Award: on receiving the E10,000 award at the Listowel Writers’ Week, Summer 2002, McGahern remarked: “Writing keeps the animals in great style”). (The Irish Times, 13 June 2002).

Musical McGahern: “My Love, My Umbrella”, “Sierra Leone”, and “Gold Watch” were adapted in a libretto by James Conway and set to music by Kevin O’Connell, being performed at the Stamford Arts Centre, England, on 9 Oct. 1997. McGahern wrote of them, ‘These three stories were all written as love stories and can even be described as changing versions of the same story.’ (Folder 633, Special Collections, Hardiman Library, UCG/NUI.) Information of Ivor Faulkner, UU MA Diss., 2007.)

Film tribute (I): Leitrim Cinemobile and the IFC jointly host a showing of McGahern’s works brought to film at Drumshanbo, Co Leitrim; screenings include Cathal Black’s award-winning adaptation of Korea (1996), and his debut short film Wheels (1976); also the 4-part BBC/RTÉ serial adaptation of Amongst Women (1998); The Rockingham Shoot (1987), tv-drama directed by Kieran Hickey, produced by Danny Boyle (dir. of Trainspotting); also Carlo Gebler’s TV scripts of The Lost Hour (from The Leavetaking) and The Key (from The Bomb Box) and two adaptations of Swallow. (See The Irish Times, 30 July 2005.)

Film Tribute (II): A film tribute was paid to McGahern on Sunday, 1 April 2007, a year after his death, with a selection based on his work incl. Cathal Black’s Wheels (1976), Kieran Hickey’s The Rockingham Shoot (1987), from a screenplay by McGahern, and two shorts adapted by Carlo Gebler (The Lost Hour, dir. Sean Cotter, 1982) and The Key, dir. Tony Barry, 1983) were screened.

John Banville: Banville writes in and Irish Times feature on Europe Day: ‘Years ago a reviewer, writing about one of my books, suggested that in my work I was endeavouring to “open a window on Europe”. I was rash enough to mention this to my friend the late John McGahern, to which, with one of his most feral grins, John retorted, “Oh, yes - and I’m trying to slam it shut!”’ (The Irish Times, Sat. 5 May 2012, Weekend, p.5.)

Mary McAleese (President of Ireland): Spoke of McGahern at the time of his death, declaring that he had ‘made an enormous contribution to our self-understanding as a people’. Further: ‘His work often pitched him into a place of some discomfort, not only for himself but for the reader also. His was a challenging voice yet not without compassion, a voice that spoke of his great and honest love for his country and its people.’

[ top ]