Life

| 1944-2020- [Eavan Aisling Boland; occas. thus on title-pages]; b. 24 Sept. 1944, Dublin; dg. of painter Frances Boland [née Kelly] and Harry [Frederick Henry] Boland (1904-1985; q.v.), Irish Ambassador to Court the of St. James [i.e., UK] - for her ‘a city of fogs and strange consonants’, and United Nations President, 1960; ed. Holy Child Convent, Killiney; London, and TCD (grad. English & Latin); appt. temp. lect. TCD 1966-68; taught creative writing in Ireland and US; New Territory (1967), a first collection, incl. translations from Irish of Egan O’Rathilly and others as will as the concluding longer poem “The Winning of Etain”, based on a 10th c. manuscript - many being ded. to Brendan Kennelly (“The Flight of the Earls”), Eamon Grennan (“The Pilgrim”), and Michael Longley; read with Austin Clarke, Brendan Kennelly, and others, at the dedication of Henry Moore’s Yeats Memorial (St. Stephen’s Green), 26 Oct. 1967; awarded Macaulay fellowship for Poetry, 1968; made translations of Horace, Mayakovsky, and Nelly Sachs; m. Kevin Casey [q.v.], 1969, with whom two dgs., Sarah and Eavan Frances; later divided time between teaching in Stanford and residence in Dublin; |

| long-term contrib. of review and literary articles to The Irish Times under lit. editorships of Terence de Vere White and John Banville - from aetat. 23; contrib. ‘The Northern Writer’s Crisis of Conscience’, a series in The Irish Times (12-14 Aug. 1970); commissioned essay for Causeway: Arts in Ulster (1971) prevented by illness and completed by Michael Longley; during the 1970s wrote poetry concerning women’s marginalisation and national identity; simultaneously developed prose critique of female literary stereotype as ‘fictive queens and national sibyls’; concerned with homemaking and domesticity in the 1980s; In Her Own Image (1980), introduced such chapter-topics as “Anorexia” and “Mastectomy”; co-founder Arlen House, Irish feminist press [Mountjoy Sq.], 1980; issued Night Feed (1982), deals with realities of motherhood; lectures widely in US, and held fellowship of Iowa International Writing Program, with Casey, in 1980; issued The Journey and Other Poems (1987) - incl. “Mise Eire”, in which the narrator is a garrison prostitute and a female emigrant, thus revising the nationalist stereotype of Kathleen Ní Houlihan, and launching the brand-name phrase ‘a kind of scar’; |

| issued Outside History (1990), re-defining reality in non-male terms; addressed IASAIL Conference on “Irish Women Poets” (Dublin 1992), tackling especially the anti-feminism of The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing [See The Irish Times, August 1992]; holder of Lannan Foundation award ($50,000); In a Time of Violence (1994); An Origin Like Water (1996); lect. at Bowdoin College, Houston U., Utah U., and Washington U. (St. Louis); invited to teach a quarter at Stanford in 1995 and received a full appointment as Mabury Knapp Chair there, 1996; elected MIAL; became subject of “A Woman’s Voice: Eavan Boland”, feature-length radio documentary dir. by Helen Shaw (RTÉ1, 21 Jan. 1996); first winner of O’Shaugnessy Prize for Irish Poetry, 1997; The Lost Land (1998); issued Code (2001), poems; New Collected Poems (2006); Boland refused to accept Aosdána nomination at an early date; she divides her time between California and Dublin; issued New Selected Poems (2014); her poem “Quarantine” short-listed for Irish Times “Favourite Poem” competition, Dec. 2014; appt. sole judge of Montreal International Poetry Prize, March 2015; |

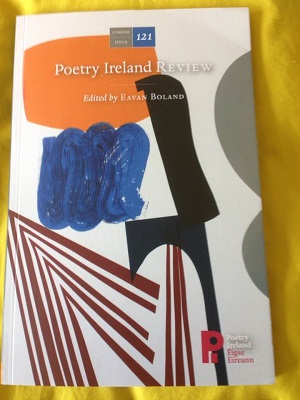

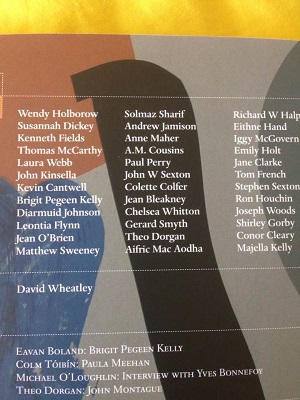

| a collection of critical essay edited by Siobhán Campbell and Nessa O’Mahony under the title of with the title Inside History: Eavan Boland was launched by Mary Robinson under the auspices of Poetry Ireland, at the Writers’ Centre, 11 Parnell Sq., Dublin, on 15 Dec. 2016; poems and essays in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, Kenyon Review, and American Poetry Review (where her essay ‘Outside History’ first appeared, March-April 1980); edited Poetry Ireland Review/Eigse, 121 (May 2017); d. Monday, 27 April 2020; her poem “Amber”, first publ. in TLS in 2012, was reprinted there at her death as “Poem of the Week”; a special issue of ABEI Journal (USP/São Paolo) was published in her honour in May 2021; in 2024 the former George Berkeley [New] Library at TCD was renamed after her when he was identified as a domestic as a slave-owner in Bermuda; her poem “Amber”, first publ. in the TLS in 2012, was reprinted there as Poem of the Week at her death. DIW DIL FDA HAM OCIL |

[ top ]

Works| Poetry |

|

| Collected & Selected Poems |

|

| Magazines |

|

| Dedicated anthologies |

|

| Criticism |

|

| Miscellaneous |

|

| [ top ] |

| Articles [sel.] |

|

| [ top ] |

| Miscellaneous |

|

|

| [ See also copious bibliographical details at The Poetry Foundation - online. ] |

|

|

| Eavan Boland edits Poetry Ireland/Eigse 121 (May 2017) | |

[ top ]

Criticism| Book-length studies |

|

| Articles & Reviews |

|

|

[ top ]

| Critical articles on Eavan Boland in issues of the Colby Quarterly |

|

| Note: Articles addressing other poets and general topics but incorporating allusions to Boland by name are also included in the Search Results for <boland> at Colby Library - online; accessed 05.11.2023.] |

| Associação Brasileira de Estudos Irlandeses, USP [Univ. de São Paolo / USP) |

ABEI Journal 23.2 [Special Issue Eavan Boland — In Her Many Images; guest eds., Gisele Wolkoff e Manuela Palacios (May 2021). CONTENTS: Wolkoff and Palacio, Introduction. Articles: Catherine Conan, ‘objects Matter: An Object-Oriented Reading of Eavan Boland’s Object Lessons‘ [17]; Maureen O’Connor, ‘“Single Out the Devalued”: The Figure of the Nonhuman Animal in Eavan Boland’s Poetry‘ [35]; Aubry Haines,'Queer Phenomenology and the Things Themselves in Eavan Boland’s In a Time of Violence‘ [51]; Pilar Villar-Argáiz, ‘Past, Secrecy and Absence in Eavan Boland’s The Historians‘ [69]; Marcos Hernandez, ‘Staring Inward: Eavan Boland’s Archive of Silences in Domestic Violence‘ [89]; Hitomi Nakamura, ‘“An Example of Dissidence”: A Reflection on Eavan Boland’s Reading of Patrick Kavanagh'[105]; Marcel De Lima Santos, ‘Boland and Yeats: Poetical Irish Dialogues‘ [119]; Caitriona Clutterbuck, ‘Bodily Vulnerability and the Ethics of Representing Woman and Nation in the Poetry of Eavan Boland‘ [133]; Emer Lyons, ‘Bodies of Water in the Poetry of Eavan Boland (IRE) and Rhian Gallagher (NZ)'[147]; Virginie Trachsler,'“Priestess or sacrifice?” Domestic Tasks and Poetic Craft in Eavan Boland’s poetry‘ [161]; Máighréad Medbh, ‘Expressing the Source: Eavan Boland and Adrienne Rich‘ [177]; Mario Murgia, ‘The Space Between the Words: A Brief Mapping of the Translation of Eavan Boland’s Poetry in Mexico‘ [183]. Poems For a Poet [authors and translators]. Marilar Aleixandre; Mary O’Malley, “domestic defeats” [200]; Moya Cannon; Gisele Wolkoff, “The Countermanding Order, 1916” [202]; Yolanda Castaño; Keith Payne, “Story of the Transformation” [206]; Theo Dorgan; Samuel Delgado Pinheiro, “Revenant” [210]; Attracta Fahy; Graça Capinha, “Encounters” [214]; Celia De Fréine; Marina Bertani Gazola, Yolanda López López, “Birthright” [216]; José A. Huguenin; Rafael Teles da Silva, “Poem for Eavan Boland” [224]; Catherine Phil MacCarthy; Marcel De Lima Santos, “Magic Circle” [228]. In Memory of Eavan Boland. Thomas McCarthy; Marina Bertani Gazola, Rafael Teles da Silva [230]; Máighréad Medbh; Mirian Ruffini, “Translation of a Kind” [213]; Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin; Jorge Rodríguez Durán, “A Shadow in Her Notebook” [234]; Jean O’Brien; Marilar Aleixandre, “Sustenance” [236]; Mary O’Donnell; Claudia Castro, “A Window in South Anne Street, 1983” [238]; Mary O’Malley; Marina Bertani Gazola, “Wolf Song” [242]; Grace Wells; Marilar Aleixandre, “Pantheon” [244]; Gisele Wolkoff, “Light in the Night for Eavan Boland” [248]. Book Reviews. Annemarie Ní Churreáin, The Poison Glen, reviewed by Antía Román-Sotelo [255]; Éilís Ní Dhuibhne, ed., Look! It’s a Woman Writer!, reviewed by Vanesa Roldán Romero [259]; Antía Román-Sotelo, Michelle Alvarenga, review of “Boland: the journey of a poet” - A delicate and powerful celebration of Eavan Boland’s life and legacy” [263]; Ingrid Casey, ed, Anthology of Young Irish Poets, reviewed by Sven Kretzschmar [267-71]. |

| —Available online; accessed 30.12.2024. |

Bibliographical details

Siobhán Campbell & Nessa O’Mahony, eds., Inside History: Eavan Boland (Dublin: Arlen House 2016) [see contents], foreword by Mary Robinson, former President of Ireland, as well as essays by Jody Allen Randolph, Patricia Boyle Haberstroh, Siobhan Campbell, Lucy Collins, Gerald Dawe, Péter Dolmányos, Thomas McCarthy, Nigel McLoughlin, Christine Murray, Nessa O’Mahony, Gerard Smyth, Colm Tóibín and Eamonn Wall. incls. poems by Paula Meehan, Michael Longley, Paul Muldoon, Sinead Morrissey, Thomas Kinsella, Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill, John Montague, Medbh McGuckian, Eiléan Ní Chuileanáin, Katie Donovan, Dermot Bolger, Jean O’Brien and Moya Cannon; also “A Poet’s Dublin”, a reissuing of the conversation that took place between Eavan Boland and Paula Meehan on the occasion of her 70th birthday in 2014.

|

| “A Woman’s Voice: Eavan Boland”, dir. Helen Shaw (RTE1, 1996) |

| [Available at RTE Archives - online] |

[ top ]

| The Eavan Boland Sourcebook (2007) | |

The Sourcebook includes a biographical introduction and chronology; introductory surveys of each aspect of Boland’s work; a representative selection of Boland’s poetry and prose writings; interviews from 1987 to 2006; reviews and critical discussions of each of Boland’s books; photographs; and a comprehensive bibliography of primary and secondary sources. Jody Allen Randolph has been a teacher and interpreter of Boland’s work for many years and gathers here a rich collection of literary and critical texts, illuminating the poet’s achievements for students and general readers alike. |

|

|

|

| —See COPAC record - online. |

[ top ]

Commentary

Rosemary Rowley, ‘Meretricious matriarchy’, review of The Journey, in The Sunday Tribune (11 Jan. 1987): ‘[...I]t is good to find an Irish woman writer who is not consumed by guilt for being in search of her own aesthetic. The Journey by Eavan Boland is a search undertaken by her, out of the freedom which allows certain questions to go unanswered and the privilege of being cushioned from hard choices others have had to make. With privilege, however, came the pain of exile [...; quotes “Mise Eire”]. Her gift of language, her precision of emotion, and her felicities of the eye and ear will win her many admirers. She has been praised for the courage of being happy, the implication beig that it takes courage to ignores some of the realities we live with. This is where I disagree. I think the personal must become the visionary if what is written today is to have any lasting value. Only in “The Journey” […] does this transformation occur. It is a poem of breathtaking daring, passion, and inspiration. That intensity which marks it, the danger of losing a child through illness, takes us on a journey in which the lost poor children of the ages are at last given a context in which the meaningless and random acts - of wilful nature and an uncaring God - show us our human responsibility. […] To my mind, there is a tendency to confuse la donnée (the given) with the poet’s act of percept (which is in fact a giving of the self.) Kavanagh understood this perfectly, as his first love was Nature. Too often in Eavan Boland’s work it provides an occasion for suburban felicity, a sort of semaphore to the reader that survival has something to do with bleached teacloths in women’s gardens and that folding them into some sort of order creates order in the larger world outside. To see the ordinary given homage in suburbia where it is a condition of life itself implies either a wilful refusal to go outside the private and face the mendacities, complicities and terror of the age, or removes such realities from the realm of conscience. This seems acceptable in Jane Austen’s day when it was a question of wars abroad, but if one is going to develop a conscience today, is a feminist conscience enough? Or is Eavan Boland nudging us towards matriarchy (presumably, no wars) in a quiet way insisting that she has only heard rumours?’. [Cont.]

Rosemary Rowley, ‘Meretricious matriarchy’ (in The Sunday Tribune, 11 Jan. 1987) - cont.: ‘Eavan Boland is a superb critic, and her training gives her an unerring instinct for what is correct textually. Very often, sadly, it is often no more than that. For example, “Tirade to the Lyric Muses[”] upbraids the lyric for celebrating beauty at the expense of truth. I think truth may not be always beautiful but its expression is. Even tragic and horrible things can be transformed by love allied to the aesthetic sense. Since Plath, surgery, poultice and bandage have had a certain currency as a metaphor for female suffering. To bandage the lyric itself is to misunderstand the nature of the question. The lyric form cannot be held responsible for the exclusion of important subject matter, voice or representation in the past, though we may deplore that exclusion. To omit female experience - as was done in the past - would be deplorable. Part of the answer must be to include female experience in all its facets while not abandoning traditional poetic forms. / The coy, “Turn your good ear / Share my music” is an invitation to a sisterhood who indulge in cliché as mind-numbing as their male predecessors. The autocracy of male poets in the tradition which must be propitiated, and the experience of the woman in a skirt of cross-woven linen in a field giving birth, leads only to the vaguest of symbols and the most tenuous of connections: flange-wheels “singing innuendos, hints, / outlines underneath / the surface, a sense / suddenly of truth, / its resonance.” Of course, asking someone to tell the truth begs the question. If Eavan Boland is going to be the figurehead of Irish women’s writing, is it enough, we may ask, if the gestures are at times a minimal but recognisable transcript of the Irish experience, as elegant and exportable as smoked salmon and as essentially consumerist. / In Eavan Boland’s first book (New Territory, 1967) there were dedications to half-a-dozen young male poets, who went on to become the male literary lions of our country today, some deservedly so. If Eavan Boland is trying to court the feminist establishment today, she has secured her audience. How permanent an audience it becomes, I think, will depend to a large extent on how confident women become in the large world outside and how much they can do away with special pleading.’ (Copy supplied by reviewer.)

Rebecca E. Wilson & Gillian Somerville-Arjat, eds., Sleeping with Monsters: Conversations with Scottish and Irish Women Poets (Wolfhound 1990), pp.79-90, contains remarks: ‘Ninety-nine days out of five its just a rock face […] The danger of inspiration is that it is a theory that redirects itself towards the idea of success rather than to the idea of consistent failure. And all poets need to have a sane and normalised relationship with their failure rate.’ ‘Yes, the voice is me. It isn’t just the voice of an “I”. It’s me in the [80] Yeatsian sense, in that it’s the part of me that connects with something more durable and more permanent in my own experience […] Very often I think that I am a human being whose window onto humanity is womanhood.. But I make a clear distinction between feminising material, which I think is unethical and restrictive, and humanising the feminine pars of an experience, which are very often potent, emblematic and powerful parts of it.’ ‘I worry about the ethical basis of poems like “Anorexic” [81]. ‘I am writing for a particular constituency within myself, from which the poetry comes. You can call it a “vision”. I think the area of private vision in any artist is impossible to find and almost impossible to define.’ ‘In her Own Image […] is not some kind of free-fall through feminist ideology. Only in Ireland [82] would it have been taken to be so. It is an examination […] of the responsibility of the poet to the silences which surround human experience.’’ Wonderful tribal echoes come in when you are raising a family’. [83; cont.]

Rebecca E. Wilson & Gillian Somerville-Arjat (Sleeping with Monsters: Conversations with Scottish and Irish Women Poets, 1990) - cont.: ‘Womanhood and Irishness are metaphors for one another. there are resonances of humiliation, oppression and silence in both of them and I think you can understand one better by experiencing the other. I am not a nationalist. it isn’t always in linear time that nations flow along and define themselves. They crystallised in different individuals, at different times, in different voices and with different echoes.’ A “nation” is a potent, important image. It is a concept that a woman writer must discourse with. I have that discourse and I like to think I have it partially on my terms. But no poet ever discourses with such a powerful image on his or her own terms. There has to be some contact between my perceptions and the national perceptions of Irish literature. When I was a young writer […] I couldn’t accept the idea of nationhood as it was formulated for me in Irish literature. Therefore, I had to find some way of resolving those two things.’ [84] ‘Irish poets of the 19th century, and indeed their heirs in this century, coped with their sense of historical injury by writing of Ireland as an abandoned queen or an old mother. My objections to this are ethical. If you consistently simplify women by making them national icons in poetry or drama you silence a great deal of the actual women of that past, who intimately depend on us, as writers, not to simplify them in this present.’ [87; quoted elsewhere as an excerpt from Object Lessons .] ‘There was a point when I realised that, as a woman poet, within the tradition of Irish poetry, I was at best marginal, and at worst, threatened by it. It took me quite a while to interpret the exact meaning of that marginality within the tradition.. But I did look at Black writing in America and dissident writing in Europe, and came to see how powerful those images were and how visible that invisibility could be. And I came to understand my own tradition and my own work better because of that.’ (pp.82-88.)

Donald Davie: ‘“I am the wrong person to review Eavan Boland’s Object Lessons”, Donald Davie wrote in one of his last reviews, published just after his death in 1995. Nonplussed by her “quite deliberately circuitous and repetitious approach, Davie found the book neither “the clear narrative of a life” nor “a sequence of essays” and as a result was “not sure I know what to do with her confidences.” (See ’Donald Davie on Critics and Essayists’, review of Seamus Heaney, Helen Vendler and Eavan Boland, in Poetry Review, 85, 3, Autumn 1995, p.39.) The feminist criticism it represents has produced “a sort of lunar landscape where I come up against concepts which Boland seems to think I shall understand whereas I understand them only cloudily and uncertaintly.” Despite these reservations, he willing conceded Boland’s central point in Object Lessons: that women have been confined to object of male representation for so long in Irish tradition that they cannot become their own poetic subjects “unless they can summon up a man’s voice, thus denying their own corporeal existence.” For all his wary sympathy [...] it is clear that Davie’s understanding of literary history has left him utterly unprepated for the bold departures of Eavan Boland’s work [...].’ (See David Wheatley, ‘Changing the Story: Eavan Boland and Literary History’, The Irish Review, 31 [Irish Futures] (Cork UP: Spring-Summer 2004), pp.103-20 [available at JSTOR online].)

Derek Mahon, ‘Young Eavan and Early Boland’ [Irish University Review, 23, 1, 1993, pp.23-28], in Journalism: Selected Prose 1970-1995 (Dublin: Gallery Press 1996), pp.105-11: reminiscences include references to ‘epistemological conversations’, as we called it.’; continuing, ‘[…] perhaps I should have paid more attention; or perhaps it’s in the nature of youthful epistemological conversation, however intense, that it should disperse in the smoke-free conditions of adult life. I am sure Eavan too has little recollection of what we actually talked about during that time, aside from the possibility of talk itself -talks about talks, you might say. This is an unfortunate and embarrassing admission, and one for which historians of Irish poetry will right give me a hard time; yet what was I to do - take notes? We were friends, still are I hope, and much of our talk was inconsequential. (p.107); remarks that ‘those were pre-feminist times, and Eavan wrote then, as she no longer does, for a notional male readership. She wanted to penetrate, indeed to dominate, the male oligarchy, but could, at that stage, do so only on their terms, or so she may have imagined. … Like Shakespeare’s Rosalind, she chose to act the man in verse, despite other modern precedents with whom, however, she was probably then unfamiliar. The poets she (we) had been encouraged to admire, from Spenser to Montague, were men; so, to be a poet, she had to be a sort of man too. She resolved this anomaly later; but for the moment it caused her, I believe, intense anguish. / Only two poems [in New Territory], “From the Painting Back from the Market by Chardin’, and “Athene’s Song”, strike a proleptically “feminist” note […] (pp.106-07); ‘Has she a cracked looking-glass in her room? A certain kind of feminist art history deplores the centuries-old cult of the female nude, especially in its commissioned form, as manipulative; but Chardin, too, in this entirely demure picture, “manipulates” his subject for artistic purposes, as Boland recognises: “he has fixed / Her limbs in colour, and her heart in line.” […] this faithful wife, domestic, whatever she was, is not about to step out of line. … Boland allows her little independence. (p.107); Mahon quotes in full and discusses in detail the poem ‘Athene’s Song’, and remarks on its attractive features’ of ‘mildness, privacy and simplicity’ as compared with the many poems of the collection that ‘strain for authority’ and ‘suffer from problems of posture and self-consciousness’(p.110); he speaks of the collection’s title invoking ‘an alternative history such as Rilke too foresaw, when the “pure” impartial lyric voice, if such a thing exists, comes into its own at last’; concluding, ‘That silent pipe in the grass, listening to the running water, is only feigning abandonment. It know, and so do we, that, whilst relinquishing nothing of its polemical force, it will be heard again in some larger, more resonant context, when the din of battle has subsided.’ (p.111). Note that Mahon selects ‘After the Irish of Egan O’Rahilly’ by Boland in Penguin Book of Contemporary Irish Poetry (1990). [See also Boland, ‘Compact and Compromise: Derek Mahon as a Young Poet’, in Irish University Review, 24, 1, Spring / Summer 1994, pp.63-66, under Derek Mahon, infra.]

[ top ]

Gerardine Meaney, ‘Sex and Nation: Women in Irish Culture and Politics’, in Irish Women’s Studies: A Reader, ed. Ailbhe Smyth (Dublin: Attic Press 1993), pp.230-44: ‘[...] It may be a shocking thought for some that the Irish woman reading Irish writing finds in it only a profound silence, her own silence. It is certainly a painful thought for an Irish woman writer and the talents of many of them must have been dissipated or lost in evading such pain. The exclusion of women was constitutive of Irish literature as it was consitutive of the Irish Republic. In her pamphlet, Boland confronts that exclusion, but even her title, A Kind of Scar, is testament to its disabling legacy (1989). “Mise Eire,” her own poem from which Boland takes that title, revised Pearse’s poem of the same name. Pearse’s refrain of “I am Ireland” became, in Boland’s poem, “I am the woman” . The myth of Mother Ireland was countered by an insistent feminine subjectivity. Boland’s LIP pamphlet counters another cultural cliché: Yeats’s “terrible beauty” is contrasted with a vision of “terrible survival” . (The centrality of the famine rather than the vagaries of nationalism to Boland’s sense of her identity as an Irish woman writer is an interesting indication of the different shape Irish history may take when women have reconstructed their part in it.) / The common insight of Clodagh Corcoran [LIP pamph. 1989] and Eavan Boland is that even where Irish literary and political culture opposes the dominant ideology of church and state it often merely re-presents [sic] the emblems and the structures of that ideology in more “enchanting” forms. One consequence of this is the cultural hegemony which the women’s movement has found particularly difficult to shatter.’ (p.239.) Later quotes - ‘According to Eavan Boland, “Irish poems simplified most at the point of intersection between womanhood and Irishness” (1989).’ (p.243.) [For full text, see RICORSO Library, “Critical Classics”, infra.]

Edna Longley, ‘From Cathleen to Anorexia’, in The Living Stream: Literature and Revisionism in Ireland (Newcastle-Upon-Tyne: Bloodaxe 1994), pp.173-95 [prev. LIP pamph. of 1990]: Eavan Boland’s feminist poem “Mise Eire” (I am Ireland) destabilises Mise but not Eire - ‘my nation displaced / into old dactyls’. There is some reluctance, partly for fear of further division, to re-open the ever-problematic, ever central issue of “Nationalism and feminism.” Later I will ask whether they are compatible.’ (p.173.) Further: ‘I was surprised that Eavan Boland’s LIP pamphlet, A Kind of Scar: The Woman Poet in a National Tradition ignored the extent to which the North has destabilised the “nation”. Boland holds to uniterary assumptions about “a society, a nation, a literary heritage’”. Troubled about “the woman poet”, she takes the national tradition” for granted - and perhaps thereby misses a source of her trouble. Because A Kind of Scar activates only one pole of its dialectic, it does not evolve the radical aesthetic it promises.’ (p.187.) Further quotes: ‘as a [187] poet I could not easily do without the idea of a nation’; ‘marginality within a tradition’; ‘the Irish nation as an existing construct in Irish poetry was not available to me.’ (Boland, pp.7-8; p.20; Longley, p.188.)

James Scruton, review of In a Time of Violence, in Irish Literary Supplement (Fall 1994): ‘Writing in a Time of Violence’, focuses on Famine Ireland, and deals with the ‘pastiche’ that comes from ‘making free with the past’; her epigraph is from Plato (‘As in a city where the evil are permitted to have authority and the good to put out of the way, so in the soul of man […] the imitative poet implants an evil constitution’; first poem’s title, ‘The Science of Cartography is Limited’, which the reviewer compares with Montague’s ‘the whole landscape a manuscript’; other poems, ‘Etty’ [a non-histrionic famine letter]; ‘Beautiful Speech’ [recalls a college thesis on the Art of Rhetoric]; ‘The Pomegranate [reflects on life as Persephone and Ceres]; ‘Anna Liffey’ [‘a river is not a woman’]; ‘Story’ [‘writing / A woman out of legend’]; ‘A Woman Painted on Leag’ [rebuttal of Keats’s urn]; ‘The Source’ [‘The adult language for mystery. Maybe. Nearly. It could almost be.’]; ‘At a Glass Factory in Cavan Town’ [‘smashed bits’ from which new glass made]; ‘At Sparrow-Hawk in the Suburbs’ [‘listening for wings I will never see’]. reviewer considers she has written herself into the very centre of contemporary Irish poetry.’ [q.p.]

Denis Donoghue, ‘The Delirium of the Brave’, review of In a Time of Violence, in New York Review of Books, 41, 10 (26 May 1994), pp.25-27: ‘Like everything else in Ireland, poetry is contentious. There is always an occasion of outrage. Two or three years ago the choice of poems in The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing made women poets feel yet again neglected, suppressed. Eavan Boland was their most vigorous speaker. With notable success she made the dispute a public issue and set radio and TV programs astir. But she is not only a campaigner. Within the past few years and after a precocious start she has emerged as one of the best poets in Ireland. When she published her first book of poems, New Territory, in 1967, it was hard to distinguish her voice from the common tone of English poetry at large: wordly, cryptic, Larkinesque. It was the book of a young poet, premature in its certitude. She needed the reading and writing of several years to achieve the true voice of her feeling. / This is the achievement of The War Horse (1975), In Her Own Image (1980), and Night Feed (1982). With The Journey (1987) and Outside History (1990) she took possession of her style. It was now clear that she could say with ease and grace whatever she wanted to say. Her new book, In a Time of Violence , does not mark a change of direction or a formal development: it is work of consolidation, culminating in “Anna Liffey”, a poem that brings together the preoccupations of several years. I should note, incidentally, that the time of violence referred to in the title is not in any direct sense the period since 1968 in Northern Ireland.’ (Concludes with brief biographical sketch.) [Available at NYRB - online; accessed 05.08.2011.]

Jody Allen Randolph, ‘The journey of a poet’, review of Collected Poems (1995), in The Irish Times (20 Dec. 1995), Weekend p.5; writes of a journey […] from the conservative exuberant formalism of her earliest work, to the radical experiment of her middle work in which she deconstructed her entire lyric position, to the formidable re-synthesis of voice, vision and technical confidence in her mature work’.

[ top ]

Elizabeth Lowry, ‘Hearth and History’, review of Collected Poems (Manchester: Carcanet 1995), 217pp. in Times Literary Supplement (14 June 1996), p.25: details progress form ‘conservative templates’ of Irish bardic and nature poetry, studied at TCD, to Nelly Sachs and Mayakovsky, remarking that ‘in spite of their rhetorical flourishes’ her ‘apprentice pieces are curiously inert; notes that In Her Own Image (1980) founds her waylaid by the Anglo-Feminist school [of] young iconoclasts imitating the crisis poetry pioneered by Plath and Sexton, complete with a Plath-like horror of the ‘brute site’ of the body; ‘Domestic Interior’, in Night Feed (1982) finally determined the direction Boland’s poetry was to take in its calm acknowledgement that ‘there is a way of life / that is its own witness’ [it] gave a new dignity and importance to her domestic role […] now expanded to include motherhood; provides the donnée refined in The Journey (1987) and Outside History (1990); a pervasive dread of littleness; hesitating between eulogising the home and militating against a growing sense of imprisonment within it; reworking of Daphne and Apollo in ‘Suburban Woman’; later poems adopt free style with connections only loosely articulated; to dg. Eavan Frances, ‘the world / is less bitter to me / because you will re-tell my story’; ‘Anna Livia’ plays with the origins of Dublin’s name to illustrate [an] essential continuity: ‘In the end / it will not mater / that I was a woman. I am sure of it. / The body is a source. Nothing more’; comments: ‘much has been written about what it means to be female, and […] Irish, as if these conditions could mean any one thing, or even any one thing in one generation. That is the kid of facile summary which Eavan Boland’s recent work wisely rejects. […] promising to be inclusive, and, in that, very moving.’

Jeanette E. Riley, ‘“Becoming an Agent of Change”: Eavan Boland’s Outside History and In a Time of Violence ’, in Irish Studies Review, 20 (Autumn 1997), p.23-29, quotes, ‘I want a poem I can grow old in. I want a poem I can die in. It is a human wish, meeting language and precedent and the point of crisis. What is there to stop me? What prevents me taking up a pen and recording in a poem the accurate detail of time passing, which might then became a wider exploration of its meaning.’ (Object Lessons, 1995, p.209); ‘The true difference poets make as authors of the poem is in sharp contrast to the part they were eroticised and distanced. A beautiful and compelling language arose around. In pastoral, lyrics, elegies, odes, they shepardesses, mermaids, nymphs.’ (Object Lessons, 1995, p.232); ‘Irish women have had a very narrow escape from being deathless and ornamental and fixed eternally in time and space in Irish poetry, so the mobility of changes is something not to be taken for granted. I never feel absolutely clear that I can move around the Irish poem with complete freedom. I had a powerful longing to be able to move just this one inch more towards a wider space within it. The sentiment of wanting a poem I could age in, embrace death in, and the liberty I took in voicing that desire with basically the same words in more than one poem are important expressions on my part.’ (‘Eavan Boland: An Interview’, Poets and Writers Magazine, 22, 6, 1994, pp.32-45.)

[q.auth.], review of Outside History, Selected Poems 1980-1990, in Irish Literary Supplement (Fall 1992), [q.p.]; notes that the new volume contains nearly a complete selection of poems from her last two collections, Night Feed (1982) and The Journey (1988), together with a large body of new work, while nine poems from the first-named are revised and arranged in a sequence called “Domestic Interior”.

Catríona O’Reilly, review of Lost Land (Carcanet 1998), notes that for Boland there is only one story and that is ‘the idea of a nation’; notes that ‘My Country in Darkness’ is the opening poem; also cites ‘Witness’ and ‘Dublin 1959’, and Formal Feeling’; speaks of Boland’s awareness of what she calls ‘sarcastic craftsmanship’ and attributes to this awareness the deliberate lack of grace, otherwise ‘a dislike of her medium’. [q. source.]

Dennis O’Driscoll, review of Mark Strand & Eavan Boland, The Making of a Poem (Norton), in The Irish Times (4 Nov. 2000): section one categorises poems according to technical means employed, i.e., villanelle, sestina, pantoum, sonnet, ballad, blank verse, heroic couplet and stanza; chapter on poetic feet; another on ‘Shaping Forms’ (elegy, pastoral, ode); ‘Open Forms’; reviewer offers some strictures mixed with praise: ‘fledgling writers who treat The Making of a Poem as a practitioners’ handbook may find themselves intimidated’; ‘when it appears in paperback, [Strand] and Eavan Boland may consider re-naming their infromative and pleasurable book The Reading of a Poem.’

Mary O’Malley, ‘Poetry, Womanhood, and “amn’t”’, in Colby Quarterly, 35:4 (Dec. 1999), pp.252-55 I first saw Eavan Boland in a small bookshop in a Galway side street. It was evening and she was reading from The Journey. I was struck by her delivery, the unique quality of her voice, understated, almost matter of fact. Her accent was unmistakably Irish, but I couldn’t give it a region. There was a certain truth in that. She is from within the Pale, but not regional. In Ireland, where a kind of spirit stomping ground is the birthright of many poets and the justification of others, that brings a certain awkwardness. So I listened, politely at first:

[...]

She did much to define the space in which I was able to grow as a writer, often in ways I neither engaged in nor fully understood. She said herself in an interview that “historically I knew I would have to pick up the tab as a woman writer”. Typically, she doesn’t complain but asserts that “to be effective and useful as an Irish woman poet you have to be able to pick up that tab”. There is no comfort in that assertion and I was inclined to resist it when I first read it but like so much of what she says, I am re-examining it in the light of experience.

Above all else, she took the trouble to read work from poets who are starting out. To read it with attention and to comment with courtesy, and knowledge. In this she shames many who would pass themselves off as critics. I almost never see Eavan Boland, and talk to her once a year at most. She once had me writing rhyming couplets for a week to knock some sparks out of my poems. She is a teacher and an inspiration to me, and along with a handful of writers, male and female, makes it possible to continue in the dark times.

—Colby Quarterly, 35:4 (Dec. 1999), pp.252-55; available - online; see also full-text copy - as attached.

[ top ]

Clair Wills, review of Code, in Times Literary Supplement (1 Feb. 2002), writes: ‘Boland is a master at reading history in the configurations of landscape, at seeing space as the registration of time. If only we know how to look, there are means of deciphering the hidden, fragmentary messages from the past, of recovering lives from history’s enigmatic scrambling far from evaporating, then [as Elizabeth Bowen says], places do speak to Boland, tell stories. She finds the tangible evidence of personal and public history in the ornaments sent home by the exile in America, in an old map found in an attic, or in the landscape at her grandmother’s grave.’ Quotes lines from “That the Science of Cartography is Limited”, called ‘one of her best-known poems: ‘the line which says woodland and cries hunger / and gives out among sweet pine and cypress, / and finds no horizon // will not be there’. Calls the sequence of eleven poems reflecting on her thirty-year marriage to Kevin Casey as ‘the undoubted triumph of this book’ (e.g., ‘what is hidden in this ordinary, ageing human love’). She concludes: ‘Eavan Boland challenges us to accept the consequences of female master, as she explores ways of writing about purpose and continuity, success and certainty.’ ( p.12.)

Eva Bourke, reviewing After Every War: Twentieth Century Women Poets - Translations from the German, in The Irish Times (15 Jan. 2005), expresses minor reservations about the poems selected and remarks on inaccuracy of translation in poems and titles, e.g., ‘Aber wie Orpheus weiss ich / auf der Seite des Todes das Leben’ wrongly translated as ‘But I am like Orpheus and I know / life on the strings of death’ (in Ingeborg Backmann’s “Dunkles zu sagen”) instead of “life on the side of death”, remarking that the poet Bachmann had been playing with the homophones Saite =string and Seite =side. Bourke notes Boland admission that she doesn’t speak German in the introduction and suggests that the publisher should have been ’doubly vigilant’ and proposes ‘versions from the german’ as a truer title.

Shirley Kelly, ‘Little belief that a woman could be an Irish poet’, interview with Eavan Boland, in Books Ireland (March 2006), quotes Boland: ‘[…] When I was a child [in England] I didn’t feel the story around me was my story. I was in England for six years of my childhood. Everything seemed to want to remind me I wasn’t in my own country - the language, the post boxe, even the fog. Probably it did make me suspicious, as you say, of the way stories were told - and readly later to look at them more closely […] Gradual[ly], I think, I had a sense that my life - which was a very down-to-earth one, in the suburbs, with a young family - wasn’t written in the Irish poem. That is, the poem I’d learned to write didn’t fit the life I actually lived. It was a very disorienting thing. I had to re-learn a way to write a poem […] It wasn’t confidence. More like a lack of alternatives. Either I put the life I lived into the poem, or else the poem I wrote would falsify the life I lived. It wasn’t a choice really. Nor was it as conscious as that. What was exciting, or troubling - maybe a bit of both - was trying to find a new language and a new way of framing a poem. […] I wasn’t considered as seriously [as others]. That was a given. At the time my subject matter, my choices, my arguments were looked at sceptically. Other poets and several critics seemed to argue that I was reducing the scope of the Irish poem. Narrowing it. Introducing women’s themes which diluted an otherwise bardic or heroic tradition. Some of the resistances to what I was doing had mirrors and reflections in the wider society. I’m not sure that ther was an easy association at that time in Ireland between the word woman and the word poet. There was very little belief that she could be an Irish poet.’ [Cont.]

Shirley Kelly (interview with Eavan Boland, Books Ireland, 2006) - cont.: ‘Was I concerned. Well, of course. I was much younger. Some of the criticism was abrasive, and some of it was very personal. But I have - and I had then - a very resisting view of what is called the accepted canon. The history of poetry shows that the margin defines the centre, not the other way around. Anyway, my mind was made up. A poetry that could not danme, honour and explores the lives of half its population was not going to continue to deserve its title as a national art. Of that I was quite sure. So, yes I was concerned. But there were also times when I felt lucky to be able to press the point. [Speaks of poetry and ‘a superb, powerful and true form of experience.’] I think most writes would say they didn’t consciously pick their form. That’s true for me. The American Raymond Carver - really a master of the short story - has a wonderful essay in which he writes about this. He describes having two lively teenagers, a noisy house - all of that. So at night he went out and sat in his car and wrote there. That way the short story form, he says, became an obvious choice for him. I love the idea that an artistic form isn’t pure - that it weaves and flutters around your day and your circumstance, and gets added to in the process. So, to answer the second part of your question, I was already a poet. But the poem, as an entity, was the perfect fugitive form for me when I had small children.’ [Cont.]

Shirley Kelly (interview with Eavan Boland, Books Ireland, 2006) - cont.: ‘The days were often busy. I often felt that the poem which ever one I was writing at the time - waited for me till I was free to pay attention again.’ [Speaks of the influence of her mother, Frances Kelly as forming her idea of ‘a practical working day for an artist’.] Further: ‘There’s a difference between the past and history. History is the official version. The past - especially in a country like Ireland - is far less clear. It’s a region of whispers and secrets and lost lives. I’ve been very influenced by that difference - that distance between past and history. A long time ago, as a poet, I aligned myself more with the past than history - at least in my own mind. I think that had something to do with being a woman - my sense of all the lives that never made it to the official version.’ Remarks of revision for Collected Poems : ‘There’s always a temptation to re-write yourself. But it’s a mistake. There’s a kind of forgery in going to work you wrote when you were younger and trying to re-shape it. You can’t do it. The work was different then. And you were a different writer then. So there’s really no going back.’

[ top ]

Bridget O’Toole, review of Object Lessons [inter al.], in Books Ireland (Dec. 2006), p.283: ‘The setting in which the seach, though not ended, found a place to settle, is the suburb wher she began her married life and had her children. The exercise book is still there but now we see also children’s tricycles, a washing machine, softly-lit streetlights, shurbs in blossom. Boland is an innovator in writing about such things and she does so with clear aesthetic perception and directness. But the question for aplace in Irish poetry is not over. It’s here that she wants to write a political poem that is not public: “I wanted ot see the effect of an unrecorded life - a woman in a suburban twilight under a hissing streetlight - on the prescribed themes of public importance.” / She goes on to explore the problems and possibilities of the sexual and erotic in poetry. Looking back on her journey she sees how her earliest concerns with verse and its techniques were almost a-sexual. Later she percieves the erotic in an apprehension of growth and passing time. Boland is morally courageous […]’

Catriona Clutterbuck on “Mise Eire” by Eavan Boland, in Irish University Review: A Journal of Irish Studies [Special Irish Poetry Issue, guest ed. Peter Denman] (Sept. 2009): Anne Fogarty correctly has argued for Boland’s awareness that the “capacity of language to revive [...] female biographies obscured by the apathy of documentary record” so as to address “the urgent necessity of tracking down the silenced, female ghosts of Irish history”, can lead to “acts of poetic conjuration [that] are in false faith”. Poets run this risk “if they assume the power to appropriate meaning or to restore a sense of completion to a history which is defined by loss and fracture”. [1] I would argue that “Mise Eire” extends the exploration of false faith it invites, by pointing to its readers’ powers of conjuration as equally answerable. To the extent that the scar which signifies the presence of a “new language” for gendered experience, is read either as a sign of ‘the damage done to women by the archetypical feminine image of nationalist texts’ [2] (in which category of injurious writings, certain critics argue, can be counted the poem under discussion here), or alternatively, is read as a triumphant proof of victory over this same damage, Boland’s poem is hoisted with its own petard: it itself becomes one of those appropriative and distorting texts. But “Mise Eire” eludes this danger by confounding such over-direct interpretations.’ Further: ‘What these critics have not sufficiently recognized is that they themselves, form part of that body politic so infected: Boland’s reconvened woman-as-nation threatens to leave them, sceptical as they are of both of the representative functions of both mythology and realism, in the dead-end, anorexic state of ‘A palsy of regrets’ over the failure of representation which many diagnose as a willed condition in Boland’s work.’

Notes: 1. Anne Fogarty, ‘“The Influence of Absences”: Eavan Boland and the Silenced History of Irish Women’s Poetry’, Colby Quarterly, XXXV, 4, Dec. 1999, 256-74; p.271.

2. Pilar Villar-Argaiz,The Poetry of Eavan Boland: A Postcolonial Reading (Dublin: Maunsel and Company [an imprint of Acadmica Press], 2008, p.127.

John McAuliffe, review of New Selected Poems, in The Irish Times (18 Jan. 2014), “weekend Review”, writes: ”[..] In succeeding collections Boland continued to rework these themes [revisionist, feminist, &c.], often projecting them on historical subjects. The excludeness of the emigrant was, though, increasingly and not always convincingly conflated with her experience of being a woman poet in Ireland. / The juxtapositions of Still Life”, for example, do not quite gel: the Irish-American painter William Harnett, “a famous realist”, left Clonakilty in 1848, ”in the aftermath of Famine. In // the same year” [McAuliffe’s itals.] as an etching of a starving woman with her dead child was published in the London Illustrated News, an image actually published in 1847. If the facts seem made to measure, does the poetry seem too much like a rhetorical exercise? A poem’s arguments can petrify or neuter the careful detain and pointed rasim that elsewhere strengthen Boland’s style. [...] The main interest of new Selected Poems, though, is the way it flags uphow Boland, 70 this year, has developed a new late style: in poems for her mother (“An Elegy for My Mother in Which She Scarcely Appears” and “Soul”) and in ”To Memory”, Boland’s worried self-consciousness about the injustice of any act of representation is still present, but it is now set out talkier, run-on lines, whose fluid, drifting syntax discovers surprising images. The book’s closing set of previously unpublished poems feels recharged and refreshed, turning away from an imprisoning past [...].” (p.13.)

David Wheatley, ‘[I]not the shadowlands: Has a poetry of myth, legacy and lost lands become a one-size-fit-all historical elegy[?]’ review of A Woman Without a Country, in The Guardian (21 Feb. 2015): ‘[...] One of the oddities of Boland’s critique of nationalism is that her poems preserve that phenomenon in something like 19th-century aspic. The revisionist view of Irish nationalism has been with us for more than half a century, after all, but the picture of Irish history that emerges from these poems is strangely timeless and unalterable. The juggernaut of the nation - callously, insensitively male - annihilates the rich particularity of female experience, but Boland’s poems gravitate with grim inevitability to a hobbled, abstract mourning. Her addiction to the full stop instead of the comma quickly grates, and the plonked-down sentence fragment as a shortcut to poetic significance (“And will never heal”, “And nothing more”, “Who will never remember this”, “So many names for misery”, “And then I leave”) produces melodrama. In the title poem, not for the first time, Boland depicts a male artist’s portrayal of the female form as an act of invasion and dissection (“cutting in / To the line of the cheek”). She has written sensitively of her mother’s work as an artist, but the male/female dichotomy she codes into the act of perception remains notional rather than proved. [...] If patriarchy never changes, the stasis of Boland’s poems might be interpreted as a desperate irony, designed to underline the helplessness that is the female poet’s lot. Yet this side of her work coexists with an unfailing belief in her mandate to speak for, or over, the heads of others, including other women. To cast oneself in such a representative role requires a rare artistic will to power, given the drama Heaney made in North of precisely not wanting to take up this role. Could it be that Boland prefers to relate to an antiquarian “Romantic Ireland”, the better to preserve her role as our deliverer from it? [...]’ (See full-text copy in RICORSO Library, “Criticism > Reviews”, via index, or direct.)

Andrew McCulloch, intro., ]“Poem of the Week”, in Times Lit. Supplement ([30] April 2020): ‘Eavan Boland [...] said she became a poet at a time when the words “poet” and “woman” were “almost magnetic opposites”, especially in Ireland, where poetry was seen as a kind of “ordained male succession” and made little reference to the physical or emotional experience of women. Perhaps the heavy political undertow in Irish poetry helps to explain why domestic themes were considered undignified by the literary establishment; the beleaguered position of the feminist community in Ireland also explains why, when she started to write, Boland had almost no tradition on which she could draw. In such circumstances, she says, there are two things a woman poet can do: include the devalued experiences that have been left out of poetry in “separatist structures”, or subvert existing structures so that they have to include them. This is also a way of dealing with other kinds of exclusion: as she points out, all Irish writers are using “someone else’s language” and having to fight through “someone else’s history”. But Boland’s subversion is not driven by feminism or postcolonialism. If she writes about the small wonders of domestic life in a tradition dominated by the monumental and the heroic, it is quite simply because, for her, the personal is political.’ (Available online; accessed 31.12.2024.)

[ top ]

Poetry

“The Oral Tradition”: ‘I was standing there at the end of a reading or a workshop or whatever, watching people heading out into the weather, only half-wondering what becomes of words, the brisk herbs of language, the fragrances we think we sing, if anything. [...; see full version in a separate window - as attached.]

“Mise Eire”: ‘I am the woman / In the gansy coat / On board the “Mary Belle”, / In the huddling cold, // Holding her half-dead baby to her’ […] ‘I am the woman - / a sloven’s mix / of silk at the wrists, a sort of dove-strut / in the precincts of the garrison / […] who neither / knows nor cares that / a new language / is a kind of scar / and heals after a while / into a passible imitation of what went before.’ [final stanza; quoted in Rosemary Rowley, review of The Journey, in Sunday Tribune, 11 Jan. 1987 [as supra]; see full version, attached.])

“Outside History”: ‘Out of myth into history I move to be / Part of that ordeal / Whose darkness is // Only now reaching me from these fields, / Those rivers, those roads clotted as / Firmaments with the dead.’ (Quoted in Marie Duffy, UG Diss., UUC 2007.)

| See “Fond Memory”, Eavan Boland’s verse reflections on Thomas Moore - under Moore, Commentary, infra. |

“The Singers” (for Mary Robinson): ‘The women who were singers in the West / lived on an unforgiving coast. / I want to ask was there ever one / moment when all of it relented, / when rain and ocean and their own / sense of home were revealed to them / as one and the same? // After which / every day was still shaped by weather, / but every night their mouths filled with / Atlantic storms and clouded-over stars / and exhausted birds. // And only when the danger / was palin in the music could you know / their true measure of rejoicing in / finding a voice where they found a vision’ (The Singers: Collected Poems, p.173; cited on Chadwyck Healey Front Page.)

| “The Singers” |

|

| —Standford Magazine (May/June 2002) - available online. |

In A Time of Violence (1994): ‘I want a poem / I can grow old in. I want a poem I can die in’ (concluding phrases; cited in James Scruton, review, ‘Promises and Disappointments’, in Irish Literary Supplement, Fall 1995, p.8); further, ‘You are watching, as light unlearning itself, / An infinite unfrocking of the prism’ (cited in Kathy Cremin, review, Irish Studies Review, Spring 1996, p.50).

| “The War Horse” |

|

|

|

| —The New Yorker (July 2001 posted on Facebook by Thomas McCarthy (20 Aug. 2019) [here cropped] |

[ top ]

| “Our future will become the past of other women” (Dec. 2018) | |

|

Imagine these women Our island that was once All those who called for it, Justice no longer blind. |

| ‘Poem by Eavan Boland’, in The Irish Times (10 Dec. 2018), illustrated by Paula McGloin - online; accessed 21.02.2022. | |

[ top ]

“My Country in Darkness”: After the wolves and before the elms / the bardic order ended in Ireland. // Only a few remained to continue / a dead art in a dying land: / This is a man / on the road from Youghal to Chairmoyle. / He has no comfort, no food and no future. / He has no fire to recite his friendless measures by. / His riddles and flatteries will have no reward. / His patrons sheath their swords in Flanders and Madrid. // Readers of poems, lovers of poetry - / in case you thought this was a gentle art, / follow this man on a moonless night / to the wretched bed he will have to make: // The Gaelic world stretches out under a hawthorn tree / and burns in the rain. This is its home, / its last frail shelter. All of it - / Limerick, the Wild Geese and what went before - falther into cadence before he sleeps: // He shuts his eyes. Darkness falls on it.’ (From Lost Land; printed in The Irish Times, 12 Sept. 1998.)

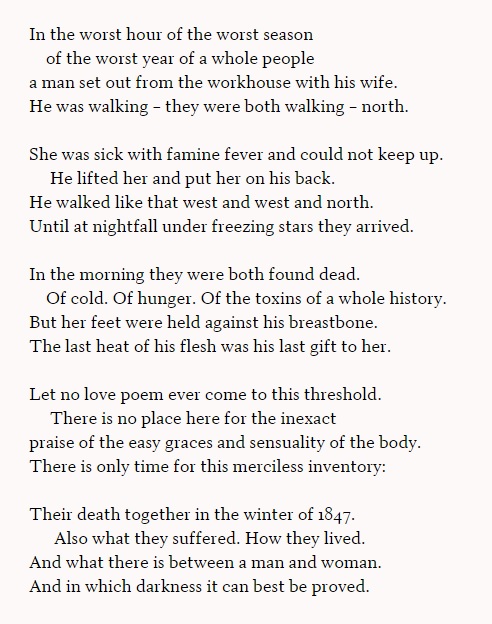

“Quarantine” (New Yorker, 4 June 2001): ‘In the worst hour of the seasons / of the worst year of a whole people / a man set out from the workhouse with his wife. / He was walking - they were both walking - north. // She was sick with famine fever and could not keep up. / He lifted her and put her on his back. / He walked like that west and west and north. / Until at nightfall under freezing stars they arrived. // In the morning they were found dead. / Of cold. Of hunger / Of the toxins of a whole history. // But her feet were held against his breastbone. / The last heat of his flesh was his last gift to her. / Let no love poem ever come to this threshold. / Three is no place here for the inexact / praise of the easy graces and sensuality of the body. / There is only time for this merciless inventory: / Their death together in the winter of 1847. / Also what they suffered. How they lived. / And what there is between a man and a woman. / And in which darkness it can best be proved.’ (p.73; also in New Collected Poems, Norton 2008.)

|

| [ Available at Poetry Foundation - online; accessed 21.01.2015. ] |

“The Art of Grief”: ‘An object of the images we make is / what we are and how we lean out and / over the perfect surface where / our features in water greet and save us. (Collected Poems, 1995, p.208; cited in Catriona Clutterbuck, ‘Gender and Representation in Irish Poetry’, in Bullán: An Irish Studies Journal, Autumn 1998, p.53.)

[ top ]

Prose

| ‘The shadow of bardic privilege still fell on the Irish poem when I was young.’ (Object Lessons: The Life of the Woman and the Poet in Our Time, NY: W.W. Norton, 1996, p.91; quoted in Thomas Dillon Redshaw, ‘“The Dolmen Poets”: Liam Miller and Poetry Publishing in Ireland, 1951-1961’, in Irish University Review, Spring 2012; available at Free Library - online; accessed 23-09-2012]. |

| ‘What I objected to was that Irish poetry should defeat them twice.’ (Object Lessons: The Life of the Woman and the Poet in Our Times, 1995; quoted in Diane Rogers, ‘She Was Radical and She Was Right’, in Stanford Magazine, May/June 2002 - available online [accessed 31.12.2024].) |

‘Aspects of Pearse’, article in Dublin Magazine (Spring 1966): ‘It is easily secretly to find Pearse’s character unsympathetic […] to feel a well-bred distaste for the efforts of that whole generation, especially Pearse. […] the hyperbolic claims for Irish literature, the mixture of nationalist and religious terminology, and still more the messianism, would seem embarrassing today. Yet anyone who does not detect the solid achievement through these distortions is open to the charge of moral obtuseness […] a man who’s days were numbered and felt them to be numbered […] he became a self-styled architect (p.47), looking over the blueprints of a nationality which he feared was becoming extinct. [...] Pearse had a vast concept of freedom. It penetrated through the categories of political and cultural freedom to the liberation of the personality itself.’ The same issue includes a review of works on W. H. Auden (pp.84-85) and a poem [by Boland].

|

| ‘Outside History’, in American Poetry Review (April-March 1990), pp.32-38 - available at JSTOR - online; 24.06.2023. |

A Kind of Scar: The Woman Poet in a National Tradition [LIP Pamph. Ser.] (Dublin: Attic Press 1989): ‘The more I thought about it, the more uneasy I became. The wrath and grief of Irish history seemed to me - as it did to many one of our true possessions: women were part of that wrath, had endured tha grief. It seemed to me a species of human insult that at the end of all, in certain Irish poems, they should become elements of style rather than aspects of truth.’ (In A Dozen Lips, Attic Press 1994, p.81; quoted in Marie Duffy, UG Diss., UUC 2007; also in Paula McDonald, PG Dip., UUC 2011.) [Cont.]

A Kind of Scar [...] (1989) - cont.: ‘My childhood was spent in London. My image-makers as a child therefore, were refractions of my exile: conversations overheard, memories and visitors […] For me, as for many another exile, Ireland was my nation long before it was once again my country, that nation, then and later, was a sucession of images: of defeats and sacrifices, of individual defiances happening off-stage.’ (Ibid.) ‘On the one hand I knew that as a poet, I could not easily do without the idea of a nation. Poetry in every time draws on that reserve. On the other, I could not as a woman accept the nation formulated for me by Irihs poetry and its traditions.’ (Ibid).]

A Kind of Scar [...] (1989) - cont.: ‘I thought it vital that women poets such as myself should establish a discourse with the idea of a nation […] rather than accept the nation as it appeared in Irish poetry with its queens and muses, I felt the time had come to rework those images by explaining the emblematic relationships between my own feminine experience and a nationalistic past.’ (Ibid.) ‘Once the idea of a nation influences the perception of a woman then that woman is suddenly and inevitably simplified. She can no longer have complex feelings and aspirations. She becomes the pasive projection of a national idea.’ (Ibid.) ‘How had the women of our past - the women of a long struggle and a terrible survival - undergone such a transformation? How had they suffered Irish history and inscribed themselves in the speech and memory of the Achill women, only to re-emerge in the Irish poetry as fictive queens and national sibyls?’ (p.81; ibid.)

A Kind of Scar [...] (1989) - cont.: ‘Marginality within a tradition [...] allows the writer clear eyes and a quick ciritical sense. Above all, the years of marginality suggest to such a writer [...] the real potential for subversion.’ (p.88; .) ‘There is a recurring temptation for any nation, and for any writer who operates within its field of force, to make an ornament of the past; to turn the losses to victories and to restate humiliations as triumphs. ... But such triumphs in the end are unsustaining and may, in fact, be corrupt. If a poet does not tell the truth about time, her or his work will not survive it. ... We depend on [future men and women] to remember [our present] with the complexity with which it was suffered. As others, once, depended on us.’ (Ibid., p.92 all the foregoing quoted in Paula McDonald, PG Dip., UU 2011.)

[ top ]

Object Lessons: The Life of the Woman and the Poet of Our Time (Manchester: Carcanet 1995): ‘There’s a huge difference between the past and history. History is the official version, it tells the story of the survivors. It is the mouth piece of those who survive the outcome. But the past is fugitive, often silent, filled with shadows.’ (q.p. quoted in Marie Duffy, UG Diss., UUC 2007.)

| Object Lessons [cont.]: |

|

|

A Journey with Two Maps: Becoming a Women Poet (Carcanet 2012) - begins with an anecdote: one afternoon, Eavan Boland saw one of her mother’s paintings for sale in a gallery, signed by her famous teacher. It is the starting point for an exploration of concepts of art and womanhood, of what it means to be a woman poet, finding her own voice within a tradition. (Publisher’s notice - online; accessed 21.09.2023).

Poets to blame: ‘I did blame Irish poets. Long after it was necessary, Irish poetry had continued to trade in the exhausted fictions of the nation, had allowed these fictions to edit ideas of womanhood and modes of remembrance.’ (In Sleeping with Monsters: Conversations with Scottish and Irish Women Poets, ed. Rebecca E. Wilson & Gillian Somerville-Arjat, Wolfhound Press 1990; quoted in Marie Duffy, UG Diss., UUC 2007.)

Heaney’s Open Letter (Field Day No. 3, 1983) - reviewed by Boland in The Irish Times: ‘Poetry is defined by its energies and its eloquence, not by the passport of the poet or the editor; ot the name of the nationality. That way lie all the categories, the separations, the censorships that poetry exists to dispel.’ (The Irish Times, 1 Oct. 1983; quoted in Edna Longley, ‘The Aesthetic and the Territorial’, in Elmer Andrews, ed., Contemporary Irish Poetry, 1992, p.[63].)

Continuing the Encounter (1993): Boland observes the tendency in Irish literature up to the 1980s to represent female identity in terms of ‘images, emblems, icons, the ornamenal parts of the poem, the passive object of the narrative.’ (‘Continuing the Encounter’ [essay-chap.], in Ordinary People Dancing: Essays on Kate O’Brien, Cork UP 1993, p.10; quoted in Paula McDonald, PGDip., UU 2011.)

Poets & the nation: ‘I thought it vital that women poets such as myself should establish a discourse with the idea of the nation. I felt sure that the most effective way to do this was by subverting the previous terms of that discourse. Rather than accept the nation as it appeared in Irish poetry, with its queens and muses, I felt the time had come to re-work those images by exploring the emblematic relation between my own feminine experience and a national past.’ (A Kind of Scar, 1989 p.20; cited in Catherine Nash, ‘Embodied Irishness’, in Brian Graham, ed., In Search of Ireland: A Cultural Geography, 1997, p.109.)

Poet & woman: ‘There is no area in which a grudging societal permission is a more malign presence than in the elusive distance between writing a poem and being a poet [particularly in] a society where the words poet and women were – until recently perhaps – almost magnetically opposites’; [cited from The Salmon Guide to Creative Writing in Ireland, by Mary O’Connor, op. cit., in Krino (Spring 1994)]; also, warns against ‘separatist ideology’ in poetry that promises the woman writer that it will ‘ease her technical problems with the solvent of the polemic [which] whispers to her that to be feminine in poetry is easier, quicker, and more eloquent than the infinitely more difficult task of being human’ (The Women Poet, Her Dilemma, Krino 1.1 (1985), cited in O’Connor, op. cit., p.33].

Nation as woman: ‘The idea of the defeated nation being reborn as a triumphant woman was central to a certain type of Irish poem. Dark Rosaleen, Cathleen ni Houlihan. The nation as woman; the woman as national muse’; [on sentimentality in Irish culture and ideology:] ‘those conventional reflexes and reflexive feminization of the national experience’. (‘Outside History’, in The American Review, March-April 1990, pp.37-49; p.42, 49; quoted in Ciaran Benson, ‘A psychological perspective on art and Irish national identity’, in “The Irish Psyche” [ Special Issue], Irish Journal of Psychology, 15, 2 & 3, 1994, p.327.)

Caveat Nationalism: ‘The love of a nation is a particularly dangerous thing when the nation predates the state.’ (Object Lessons, 1995, p.12). Further, ‘In previous centuries, when a poet’s life was an emblem for the grace and power of a society, a woman’s life was often the object of his expression, in pastoral, sonnet, elegy. As the mute object of his eloquence her life could be at once addressed and silenced.’ (Ibid.; quoted in Kathy Cremin, review, Irish Studies Review, Spring 1996, p.50.)

[ top ]

Northern Crisis: ‘The situation in the North is one of great complexity. Yet it always enacts itself, dramatises itself on the streets and in the ordinary passions of people, in terms of brutal simplicity.’ (Eavan Boland, ‘The Northern Writer’s Crisis of Conscience’, [series] The Irish Times, 12-14 Aug. 1970; cited in Richard Deutsch, ‘“Within Two Shadows”: The Trouble in Northern Ireland’, in Patrick Rafroidi and Maurice Harmon, eds., The Irish Novel in Our Time, l’Université de Lille 1975-76, pp.132-54; p.148.)

Subversion: ‘The old élite narrative of the self-conscious artist is being subverted and refreshed by different concepts of story-telling - more oral, less singular, more rooted in the communal drama’. (The Irish Times, 21 August 1993.)

Irish Literature, ‘Daughters of Colony: A Personal Interpretation of the Place of Gender Issues in the Postcolonial Interpretation of Irish Literature’, Éire-Ireland, 32, 2 & 3 (Summer / Autumn 1997), pp.9-20: ‘I had a passion for my country’s literature long before I had a place in it. Many young writers feel that. But in my case the feeling continued long past my rational acceptance of it. When my knowledge caught up with my passion, when I began to understand the tradition I came from, when my work still seemed placeless within it, I became both curious and troubled. This piece is about my unease, my observations of it, and the conclusions I drew.’ (p.10.) ‘I intend to argue here that there is a distance - a crucial and defining distance - between the past and history. […] The distance between the past and history should not only be part of post-colonial studies. It should also be seen and charted as the place where so much of the energies of Irish literature originate.’ (p.12.)

‘The Weasel’s Tooth’: Eavan Boland ‘takes a personal look at the problem of the writer in Ireland now’ in response to the recent bombing of Dublin and death of innocents (The Irish Times, 7 June 1974, p.7): sSpeaks of writing the article with ‘authentic reluctance’ and remarks: ‘William Yeats, understandably and regrettably, needed a fantasy of cultural coherence - of Anglo-Irish pride and peasant simplicity - ... I must be private rather than personal […] As a lyric poet, particularly as a lyric poet who is a woman, I feel my contribution must be not to grieve for the child, but to explore carefully, sympathetically, finally with love, the evil which could cause that death […] I must search out the evil intrinsic in femininity, that special evil which could cause a Nazi woman to make lampshades of the skins of her sisters, or a girl at an airport to gun down a child she could have borne herself […] In this work I should be nothing so heroic as a pioneer. For this exploration by women of the evil intrinsic in womanhood has started with Wuthering Heights, and decided in the strong codes of Emily Dickinson’s. It may even be said that Sylvia Plath, by her suicide, by her bravery, by too much identification, fell in the front line of the attempt on new territory’; ‘Let us be rid at last of any longing for cultural unity, in a country whose most precious contribution may be precisely its insight into the anguish of disunity; let us be rid of any longing for imaginative collective dignity in a land whose final and only dignity is individuality. For there is, and at last I recognise it, no unity whatsoever in this culture of ours.’ (Cutting in John Hewitt Collection, UUC; undated scrapbook c.1974; also cited in Robert Garrett, Modern Irish Poetry, Tradition and Continuity from Yeats to Heaney, 1986 [q.p.].)

Love Orange, Love Green [Working Class Ulster Poetry]: Boland, reviewing the anthology of this name, recalls a conversation with the US crime-writer Jimmy Breslin, in which her question about the cause of the descent of the city into terror is answered not with institutionalised violence, the police, and so forth, but with ‘little murders’; the book under review claims to be the ‘response of working-class Ulster to the humiliation, the anguish, and the terror of five years. Regrettably it must be said that it appears instead in ballads like UVF to be no such thing. Instead, it seems a recurrence of the tradition, always with a siren appeal to the Irish, of the glamorisation of little murders.’ (The Irish Times, 21 Jan. 1975, p.8).

Ideology & criticism: ‘[O]ver the past twenty years their emphasis has got still more inexact. Feminism, populism, multi-culturalism have been quickly taken in - particularly by the academy - with little regard for their complexity, and regurgitated as an odd series of updates about what poetry is and who writes it. […] the real trouble is that these arbitrations hide from view the delicate and important connections between traditions, poets, voices and visions’ (review of P. Mariani’s biography of Robert Lowell, in The Irish Times, 21 Jan. 1995). Boland compares the biography favourably with is predecessor by Ian Hamilton, ending with a comment on ‘Lowell’s wonderful achievement’.

‘Donald Davie was a wayward, passionate, honourable, quirky, insistent critic. His love of poetry was intense. He brought unfashionable ethics to an old art. Conscience, anger, engagement - attributes not always associated with criticism - could shine out of his discussion of a single poem. He was a fine poet himself and his tastes were both interesting and unpredictable.’ Boland writes that she has never forgotten the ‘generosity of Davie’s attack’ on Larkin’s edition of 20th Century Oxford Book of Modern Verse (1973), in a Spectator critique that was ‘notable for its vigilance, its lack of mean-spiritedness’. [Davie taught English at TCD in the 1950s; d. 1995.]

Sheila Wingfield (whom she visited at the Shelbourne Hotel in 1966) ‘The conversation I had with her that day has stayed with me all my life. She was the first woman poet I ever met. I saw somebody out of their life say to me: “I’m a poet and I’m a woman.” Nobody else had ever said it to me. [..., &c.]’ (See under Wingfield, infra.)

[ top ]

References

Grattan Freyer, ed., Modern Irish Writing (1979), selects “New Territory”; “The Other Woman”; “The Hanging Judge”; “Child of Our Time”; “The War Horse”.

Peter Fallon & Seán Golden, eds., Soft Day, A Miscellany Of Contemporary Irish Writing (Notre Dame / Wolfhound 1980), contains “Song”; “The Gorgon Child”; “Menses”.

Katie Donovan, A. N. Jeffares & Brendan Kennelly, eds., Ireland’s Women (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1994), “Mise Eire”, from Selected Poems (1989); extract from A Kind of Scar .

Andrew Carpenter & Peter Fallon, eds., The Writers: A Sense of Ireland (Dublin: O’Brien Press 1980), contains “The Ballad of Beauty and Time”, with photo-port., pp.20-22.

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day Co. 1991), Vol. 3 selects from New Territory, “New Territory’, from Night Feed, “Night Feed”, “Ode to Suburbia”, “The Woman Turns Herself into a Fish”; from The Journey and Other Poems, “The Journey”, “The Irish Emigrant” [1394-97]; BIOG, p.1434; Bibl. includes Selected Poems (Carcanet 1989); Outside History, Poems 1980-90 (NY: Norton 1990).

Patrick Crotty, ed., Modern Irish Poetry: An Anthology (Belfast: Blackstaff Press 1995), selects “Listen, This Is the Noise of Myth” [272]; “Fond Memory” [275]; “The Black Lace Fan My Mother Gave Me” [276]; “The Latin Lesson” [277]; “Midnight Flowers” [278]; “Anna Liffey” [279].

Hibernia Books (1996) lists ‘Irish Women Writers’, Colby Quarterly, 1 [essays on Ulster poets, Eavan Boland, Julia O’Faolain, et al.]; ‘Contemporary Irish Drama’, 4 (1991) [essays on Barry, Friel, Murphy, and women playwrights]; ‘Contemporary Irish Poetry’, 4 (1992) [essays on McGuckian, Meehan, et al. Also, Poems on the Underground [poster] (British Council: British Library n.d.), ‘The Irish Emigrant’.

[ top ]

Notes

Anne Stevenson’s response to Boland’s essay ‘Outside History’ is the subject of a critique by Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill in Theresa O’Connor, The Comic Tradition in Irish Women Writers (Florida UP 1996), pp.8-20 [see under Montague, infra.]

Nicholas Murray, review of A Life of Matthew Arnold (London: Hodder & Stoughton), notes that Eavan Boland calls Arnold her ‘anti-hero’ because he ‘took the fluid moment and set it in stone’. (The Irish Times, 15 June 1996, Wk., p.10; see further under Arnold.)

Clodagh Corcoran, reviewing Patricia Boyle Haberstroh, ed., My Self, My Muse: Irish Women Poets Reflect on Life and Art (Syracuse UP 2001), in Books Ireland (Nov. 2001), quotes Boland on her own attempts to transcend the ‘restrictions and flawed permissions’ of the male voice, and the ‘reordering of the Irish poem that women poets have accomplished’. Also Ní Chuilleanáin: ‘[An] Irish woman writing in the internatoinal void of English has to define herself in relation to a vital masculine tradition and reach out to a rapidly developing movement of women’s writing all over the world.’

Pilar Villar-Argáiz, author of Eavan Boland’s Evolution as an Irish Woman Poet and Outsider Within an Insider’s Culture (Edwin Mellen 2007), lectures at Granada, Spain, and received her doctorate in Irish studies. See Books Ireland, Oct. 2007, p.229.

Against Love Poetry (W. W. Norton 2001) - Norton notice: ‘these powerful poems are written against the perfections and idealizations of traditional love poetry. The man and woman in these poems are husband and wife, custodians of ordinary, aging human love. They are not figures in a love poem. Time is their essential witness, and not their destroyer.’ [Available at Google Books - online].

[ top ]