Life

| 1959- ; b. 6 Feb., Finglas, Co. Dublin; ed. St. Canice’s and Beneavin College; son of a merchant-sailor from Wexford; suffered the early death of his mother, 1969; supported in his writing ambitions by siblings; with his sister June [Considine - as infra] he attended a writers’ workshop run by Anthony Cronin and Sean McCann at the People’s House on the Grand Canal; worked as a factory hand, 1978-79; a library assistant, 1979-84; appt. lit. dir. of Grapevine Arts Centre; fnd.-member of Irish Writers’ Co-Operative, with Neil Jordan, Ronan Sheehan, Steve MacDonagh, and others; fnd. dir. Raven Arts Press, 1979; Arts Council Member, 1989-93; member of Aosdána, 1991; works incl. The Habit of Flesh (1979) , poems; other collections include Finglas Lives (1980), No Waiting America (1982), Internal Exiles (1986), and Leinster Street Ghosts (1989), containing the longer poem “The Lament for Arthur Cleary”, a stage-adaptation of which won the Edinburgh Fringe award 1989, under direction of David Byrne of Wet Paint, with dramaturg Maureen White; m. Bernadette [“Bernie”, née Clifton], a nurse, with whom he had two children, Donnacha and Diarmuid; |

| issued Blinded by Light (Abbey Peacock 1990), winner of Whitbread Prize; In High Germany (Gate 1990), premiered at Dublin Theatre Festival and later filmed by RTÉ (1993), featuring three Irish football fans who follow their international side abroad for the 1988 European Championships; played at Irish Arts Centre, NY 1993; re-shown in Two Lives series (RTÉ 1, Thurs. Nov. 3, 1995), also produced at Edinburgh Festival, 1995, making him the only writer to win at Edinburgh twice; The Holy Ground (Gate Theatre 1990), played with In High Germany under joint title “The Tramway End”; One Last White Horse, premiered at Dublin Theatre Festival (Peacock 1992); novels incl. Night Shift (1985), telling how Donal Flynn copes with his girlfriend’s pregnancy, a rushed marriage, and the brutality and sadness of the underside of city life, won the Macauley Fellowship; |

| [ top ] |

| issued The Woman’s Daughter (1987, rev. 1991), a tale of incestuous love with a hidden offspring and the abuse of women in small-town Ireland, written in three parts set in different periods; received Macaulay Fellowship, 1987; shortlisted Hughes Fiction Prize, 1988; winner of Guinness Peat Award, 1989; The Journey Home (1989), a story of the ‘crazy, unofficial lives’ of Hano [Francis Hanrahan], Katie and Shay, and particularly the latter couple’s flight from Dublin after having murdered the head of the Plunkett dynasty which brought about Shay’s death and abused Hano; ends with their taking shelter in the “big house” of a humanitarian old Ango-Irish lady, evicted by her Irish rural neighbours; became an Irish best-seller in Viking edn. of 1990; |

| issued Emily’s Shoes (1992), an exploration of fetishism and the roots of a man’s unhappiness], shortlisted for Irish Times/Aer Lingus Prize, 1992; issued A Second Life (1994), involving a formerly adopted child’s search for his real mother now he is a man, taking him to the Irish village where she lived; also April Bright (Peacock, Aug. 1996), a play; ed. The Bright Wave: An Tonn Gheal (1986), anthology of translated contemporary Gaelic poetry, and ed. Letters from the New Island (1987-89), pamphlets series; ed. Invisible Dublin: A Journey through Dublin’s Suburbs (1991), ‘an attempt to chronicle the lives of the new Dubliners ...’); also ed., The Picador Book of Contemporary Irish Fiction (1993), asserting prefatorially that the new writers are ‘drawing on deep reserves to drive literature into a state of renewal’ (xvi), so that ‘the centre is shifting in Irish writing’ (xx); corrected and reissued in 1994; |

| [ top ] |

| executive editor of New Island Books in 1992 after collapse of Raven Arts Press; awards incl. AE Memorial Award; awarded Macaulay Fellowship, and received the Sunday Tribune Arts Award; issued Father’s Music (1997), a novel of Dublin gangsterdom; winner of The Stuart Parker BBC Award and Samuel Beckett Award in 1990 and the Æ []George Russell] Memorial Award in 1996; conceived and ed. with Paul Daniels, a collective ‘novel’ comprised of chapters by Irish writers each set in a different room of Finbar’s Hotel (1997), incl. commissioned chapters by Jennifer Johnston, Colm Toibin, Roddy Doyle, Anne Enright, Hugo Hamilton, et al.; issued New and Selected Poems (1998); Temptation (2000), a novel; issued The Valparaiso Voyage (2001), dealing with the return of a troubled Irishman and his relationship with a Nigerian asylum-seeker and people from his past; suffered the death of his wife Bernie (aetat. 51), May 2000; Anthony Cronic contrib. an affectionate obituary to the Sunday Independent (30 May 2010); |

| DB issued The Reed Bed (2002), poetry; wrote Départ Et Arrivée, a play with Paris-based Iranian writer exile Kazem Shahryari (Paris Arts Studio, Nov.-Dec. 2004); also, a new play about three generations of two Ballymun families, These Green Heights (Axis Arts Centre, Ballymun 24 Nov. - 11 Dec. 2004); reviews TV for The Village ; issued The Family on Paradise Pier (2005), ficitonalised family saga based on the Anglo-Irish Goold Verschoyles of Donegal; issued Dialogue in Fading Light: New and Selected Poems (2005); writer in residence to S. County Dublin, and ed. County Lines: A Portrait of Life in South Dublin County (2006); also Walking the Road (Tallaght Arts Centre April 2007), a play on Francis Ledwidge; issued External Affairs (2009), poems; ed., Night and Day: Twenty-four Hours in the Life of Dublin City (2009), incorporating 50 of his own poems and others by South Dublin poets, each with photo; issued a re-write of his 1993 novel A Second Life (2010); |

| issued New Town Soul (2010), a novel for young readers set in Blackrock, Co. Dublin, involving teenagers Joey, Shane, and Geraldine, and an elderly schizophrenic living as a vagrant in Castledawson [for Frascati] House; wrote The Parting Glass (2010), a play resuming the story of Eoin of IN High Germany, now settled there and deciding to return to Ireland; it features the Thierry Henry hand-goal that kicked Ireland out of the FIFA World Cup as a metaphor of the place of Ireland in the European Union, set during the economic down-turn; premiered at axis Ballymun, with Ray Yeates as Eoin, 1 June 2010; toured Ireland, Bolger and his wife Bernie are the dedicatees of Sebastian Barry’s On Canaan’s Side (2011); |

| his RSC-commissioned stage-adaptation of Joyce ’s Ulysses of 1993 was staged by Tron Theatre Co. (Glasgow), and in Belfast as part of the Belfast Festival at QUB, October 2012, afterwards touring Dublin (Project Arts Centre) and Cork (Everyman Th.); published collected poems as That Which is Suddenly Precious (2015); issues Lonely Sea and Sky (2016), the story of young Jack Roche of Wexford in the wartime Irish Merchant Navy, based on his father’s experience and on an incident from 1943 when the crew of an Irish vessel risked their lives to rescue 168 shipwrecked German sailors; June Considine is a sister; issued An Ark of Light (2018), a novel about a woman who strikes out for independence and becomes a caravan lady and a beacon of kindness in Co. Mayo; launched at Hodges Figgis, 6 Sept., 2018; June Considine [infra] is his older sister; issued Hide Away (2024), a novel about four inmates of Grangegorman Mental Asylum in 1941. FDA OCIL |

|

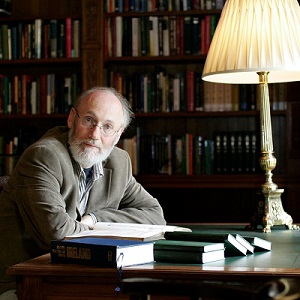

| Dermot Bolger (Facebook Profile, Oct. 2015) |

New Island (publisher) writes: "You are warmly invited to join us in celebrating the publication of three new releases from Dermot Bolger: his latest poetry collection Other People ’s Lives along with new editions of two bestselling novels A Second Life and The Lonely Sea and Sky."

|

[ top ]

Works| Poetry |

|

| Fiction |

|

| Plays |

|

| Miscellaneous |

|

| Journalism (selected:) |

|

| [ top ] |

Bibliographical Details

Invisible Dublin: A Journey through the Dublin Suburbs, Ed. & intro. Dermot Bolger (Raven Arts P. 1991), 178pp. [ded., ‘For my father and in memory of my mother, a Wexford lad and a Monaghan girl, two new Dubliners’]; Ferdia MacAnna; Roddy Doyle [Dead Bones and Chickens ]; Sara Berkeley; Hilary Fannin; Aileen O’Mara; Paul Kimmage; June Considine; Podge Rowan; Deirdre Purcell; Michael O’Loughlin; Sebastian Barry [Mountjoy Square 1974 ]; Peter Sheridan; Aidan Murphy; Francis Stuart; Noel McFarlane; Fintan O’Toole; Gene Kerrigan; Nell McCafferty; Kieran Fagan; Leland Bardwell; Heather Brett; Annette Halpin; Eamon Dunphy; Eavan Boland [The Need to be Ordinary ]; Conleth O’Connor; Joe Jackson; no biog. notices. (See longer notice in RICORSO Bibliography > Anthologies - via index as attached.)

Picador Book of Contemporary Irish Fiction, ed. Dermot Bolger (London Picador 1993; corrected edn. 1994), 518pp. Authors included: John Banville [from Mefisto ]; Leland Bardwell [The Hairdresser ]; Sebastian Barry [from The Engine of Owl-Light ]; Mary Beckett [Heaven ]; Samuel Beckett [For to End Yet Again ]; Sara Berkeley [The Sky’s Gone Out ]; Dermot Bolger [from The Journey Home ]; Clare Boylan [Villa Marta ]; Shane Connaughton [Ojus ]; Mary Dorcey [The Husband ]; Roddy Doyle [from The Snapper ]; Anne Enright [Men and Angels ]; Hugo Hamilton [from Surrogate City]; Aidan Higgins [from Balcony of Europe ]; Desmond Hogan [from A Curious Street ]; Jennifer Johnston [from The Christmas Tree ]; Neil Jordan [Last Rites ]; Molly Keane [from Good Behaviour ]; Maeve Kelly [Orange Horses ]; Benedict Kiely [from Proxopera ]; Mary Lavin [Happiness ]; Mary Leland [from The Killeen ]; Eugene McCabe [Cancer ]; Patrick McCabe [from The Butcher Boy ]; John McGahern [High Ground ]; Tom McIntyre [The Man-Keeper ]; Bernard MacLaverty [Between Two Shores ]; Bryan MacMahon [A Woman’s Hair ]; Eoin MacNamee [If Angels had Wings ]; Deirdre Madden [Remembering Light and Stone ]; Aidan Matthews [Incident on El Camino Real ]; Gerardine [sic] Meaney [Counterpoint ]; Brian Moore [The Sight ]; Val Mulkerns [Memory and Desire ]; Eilís Ní Duibhne [Blood and Water ]; Edna O’Brien [from What a Sky ]; Bridget O’Connor [Postcards ]; Joseph O’Connor [Mothers were All the Same ]; Sean O’Faolain [The Talking Trees ]; Michael O’Loughlin [A Rock-’n-Roll Death ]; David Park [Oranges from Spain ]; Glenn Patterson [from Burning Your Own ]; Francis Stuart [from Black List, Section H ]; Colm Tóibín [from The Heather Blazing ]; William Trevor [The Ballroom of Romance ]; Robert McLiam Wilson [from Ripley Bogle ]; Biographical notes [titles without dates], 509-518pp.; Julia O’Faolain, review of Dermot Bolger, Temptation (Flamingo), pb., in Times Literary Supplement, 16 June 2000, p.25. (See longer notice in RICORSO Bibliography > Anthologies - via index as attached.)

[ top ]

Criticism

|

|

[ top ]

Commentary

Shaun Richards, ‘Progressive Regression in Contemporary Irish Culture’, [pt. 3 of] ‘The Triple Play of Irish History, in Irish Review, Winter-Spring 1997, pp.38-39, remarks on In High Germany : ‘It is a survey of the accumulated cultural and economic failures of modern Ireland; but it is also a denunciation of an essentialism which brutalised more than liberated’. Richards quotes Eoin: ‘All my life it seems, somebody somewhere has always been trying to tell me what Ireland I belonged in’ and comments that the only Ireland he can relate to is a football team with a ‘menagerie of accents’. (p.40.)

Rüdiger Imhof, review of Contemporary Irish Fiction, reviewed with other works (Linen Hall Review, 10.3; Winter 1993), ‘rag-bag ... loquacious, singularly silly introduction ... [the present book] offers forty-six examples ... after 1968 ... its raison d’être remaining undiscernible. Nothing by Brian Moore, James Plunkett, John Broderick ... one finds Aidan Mathews, Colum Tóibín, Shane Connaughton, Sebastian Barry, and the ed. himself – writers who have scarcely cut a figure on the fiction front ... smacks of you-scratch-my-back ... . Note, Raven Arts and New island imprints constantly criticised by Books Ireland ‘First Flush’ for [this imprint criticised for orthographical slackness as in edition of Ledwidge poems (1993).

Carol Birch, ‘The Last of their Kind’, review of Father’s Music, in TLS (4 April 1997); Tracy … is one such lost soual, the kind of silly girl who shrieks loudly in the street with her friends, hoping to be looked at. Having run away from her stultifying family life, she lives an amoral, hedonistic life on the London rave scene, dedicated to the pursuit of fun. Abandoned as a baby by her Irish diffler father, she finds herself, at odd moments on the hung-over mornings in all-night record stores sneaking a listen to crackly field recordings of the old Sean-nós singers of the West of Ireland. When Tracey meets Luke, a married Irish businessman, she embarks on an affair …; notes that Bolger uses depictions of contemporary ugliness as a vehicle for a deeply romantic vision. Also reviewed by Jack Hanna, Irish Times [?12 March 1997].

Catriona Reilly, review of Taking My Letters Back (New Island), in Irish Times, 16 Jan. 1999; characterises author as witness to Dublin working-class life and keen and sympathetic observer of difficulties of estate and highrise existence; ‘the sheer spitting anger of this work is admirable’; Bolger drawn to atrocity; cites ‘Stardust Sequence’; ‘Blasphemy’ [dealing with abuser Brendan Smyth], ‘Bluebells for Grainne’, ‘Botanic Gardens: Triptych’; ‘unvarying line lengths and metre, and the over-suse of full rhyme, and verbal bagginess [...] mean that Bolger fails to achieve for Dublin what Carol Ann Duffy or the gritty Tom Leonard have done for Scottish city life’; ‘ultimately, this is a poetry that lives in its detail’; ‘makes a success of its defiantly humanist arguments’.

[Q.auth..], review of Emily’s Shoes (Viking 1992), in Times Literary Supplement (12 June 1992): the story of Michael MacMahon, an early-orphaned shoe-fetishist and reclusive Dublin librarian for whom life is frigid celibate affair “thawed only by my brief and solitary encounters with shoes”. His aunt Emily establishes his fetish; aged eleven, in his dreams he fondles her breasts and finds them “like hard sculptured plastic, as smooth to the touch as patent shoe leather.” Clare, the girl with whom he most conspicuously fails to make contact (“shoes are alright, but feet are nicer when you learn to play with them”), us extensively agitated by Catholicism, and harbours a trauma of sexual abuse in a Canadian childhood. Michael’s story ends with a climactic visit to a “Visions Field” beyond Ballyboughal where the Blessed Virgin fails to appear, but he is nevertheless possessed by “a glowing compassion and concern”. Peter Kemp enumerates the Catholic iconographies of the text and concludes, ‘like much else in the book, this lurch from soles to souls fails to secure a foothold on credibility.’ (Times Literary Supplement, 12 June 1992, p.20.)

Gerry Smyth, The Novel and the Nation: Studies in the New Irish Fiction (London: Pluto Press 1997), pp.76-79: [Regarding ‘the formation of identity in relation to place’]: ‘Whereas Doyle set his books in the fictional, albeit typical, area of Barrytown, Bolger maps a much more literal city, describing an urban landscape familiar to many readers of Irish fiction and to most Irish people. But if the geography is local, the actions described - lust, prostitution, hypocrisy, corruption are all part of a much wider condition for which the new Dublin is seemingly not prepared. The Journey Home is thus as much anthropological and polemical as novelistic in its orientation, constructed by its author to shock a complacent Irish bourgeoisie with its angry portrayal of a disaffected, betrayed Irish generation.’ (p.77.)

[ top ]

Harry Browne takes the mickey out of Dermot Bolger’s story “Let’s Dance”, in which a 12-year old girl Eva (‘a virago’, acc. to her [mother]) experiences incestuous feelings for her brother Art, who is covered with gore from a mackerel hunt. (1 Dec. 2001). Browne writes: ‘Yuck, there might be some symbolism there all right, and we’ll permit Bolger the heavy indulgence. It’s too bad all our blood-spattered images this week weren’t in the name of Art.’ (Irish Times, Radio Review, 1 Dec. 2001, Weekend, p.6.)

Desmond Traynor, review of The Valparaiso Voyage (Flamingo): Brendan Brogan, compulsive gambler, banished to garden shed to become ‘Hen Boy’ when his widowed father remarries a young woman, Phyllis, who brings her previous child Cormac with her; conflict with Pete Clancy, son of bullying Fianne Fáil-man; returning to Dublin-Navan in the current period of economic boom, ten years after faking his own death in a Scottish train crash to escape debts and provide for his wife and son out of the insurance, Brendan rescues a Nigerian woman Ebun from a racist attack; re-encounters his childhood antagonists; literary detective fiction ending in shoot-out. Traynor remarks, ‘What is striking [...] is that it is when Bolger is concentrating on the more personal and intimate details of his central character’s life, and his tangled, fraught and emotionally ambivalent relationships with his prevaricating father, with the insecure Phyllis, with the gay Cormac, and the equally gay Conor, that the writing hits its truest and most resonant stride, and mines a deep vein of feeling.’ (Books Ireland, March 2002).

Julia O’Faolain, review of Dermot Bolger, Temptation (Flamingo), remarks on his ‘grim surveys of Dublin and its shifting Zeitgeist’. Further, the author on record as saying of one of his books he ‘wanted it to be like Dickens or Graham Greene’; set in FitzGerald’s Hotel, haven of well-heeled families; ‘Whereas Bolger’s earlier work uses damaged children - or adults who have been damaged in childhood - to show up the wickedness of Ireland’s villains, he has no flipped his narrative coin to focus on the fragility of rectitude and the strains of parenting’; concerns Alison and Peadar Gill; arrival of Chris, a former boyfriend; reviewer cites limitations of character’s idiom dialogue and tenders criticism: ‘Picaresque novels like Bolger’s earlier ones can just about get away with broad effects … and in the past reviewers have been indulgent about this tin ear for speech patterns. When focussing on characters’ inner lives, however, middle-class self-scrutiny requires subtler insight than the prose can here provide.’; characterises Alison as belonging to new, suddenly prosperous, creedless bourgeoisie ‘whose dazed psyche offers at least as much challenge as the underworlds which Bolger has so vividly described elsewhere’. (Times Literary Supplement, 16 June 2000, p.25.)

Anne Fogarty, ‘Sex, power and revenge in modern Ireland’, review of The Valparaiso Voyage (Flamingo), remarks that Bolger’s new novel ; ‘fuses searing reportage of contemporary Ireland, traversing all of its instantly recognisable ills - corruption, racism, provincialism and shameful episodes of emotional and sexual abuse - with the stylised conventions of a thriller’; ‘above all a telling exploration of the dark aspects of masculinity’; ‘symbolically emotional and political abuse intertwine’; ‘provocatively sexualises all male familial relations and uses homosexuality as a metaphor for the lost bonds between father and son and between male siblings’; ‘The [novel] is, however, about the prospect of return rather than exile’; ‘nonetheless [...] insistent on vindicating the seemingly failed father figures who have presided over this unregenerate society’; ‘his investigation [...] help him to understand his father’s coldness and violence and even to affirm his Fianna Fáil-style rectitude despite his involvement in crooked planning deals’. Fogarty concludes, ‘In using the raw sociological data of contemporary Irish life as the basis for a compelling and expertly executed thriller, Dermot Bolger has produced a polished fable for our times [... b]ut the closure sought by this tale of male self-discovery remains an impossible goal that eludes even the reach of fantasy.’ (The Irish Times [Weekend], 2 Nov. 2001.)

Jonathan Keates, review of Dermot Bolger, The Valparaiso Voyage (London: HarperCollins), 385pp., in Times Literary Supplement (16 Nov. 2001), p.24: ‘As the destiny and horizons of its narrator, Brendan Brogan, shift and change, so too does the Ireland in which the novel is mostly set. The drama here is one of socio-economical change, as ould sod turns into Euroland and an entire value system winces and buckles under the metamorphosis.’ Keates summarises a plot in which Brendan’s father Eamonn marries Phyllis after the death of his wife, and his banished to the hen house, while her son Cormac, the favoured child, protects Brendan against the sexual abuse they both endure before flying off to ‘a more authentic homosexual experience’ [Keates] in Dublin; Eamonn is murdered; trail leads to Barney Clancy, whom Eamonn served as henchman; Barney’s malevolent son Pete becomes the object of Brendan’s vengeance, having faked his own death and assumed the identity of Cormac. It is Ebun, the Nigerian woman, who finally pulls the trigger on Pete Clancy. Keates remarks, ‘Essentially, this is a tale of Irish fatherhood in its various avatars, stern, combatant, sentimental, guilt-wracked, almost everywhere dysfunctional’. Keates questions the mix of genre - thriller and search for a father - but finds the journey taken ‘worthwhile’.

[ top ]

Conor McCarthy, Modernisation: Crisis and Culture in Ireland 1969-1992 (Dublin: Four Courts Press 2000) [Chap. 3], pp.135-64: ‘The ideological polemic of the novel [The Journey Home ] is directed at the idea of a bourgeoisie that has rural origins.’ (p.156.) ‘The novel, and O’Toole’s article [‘Going West ...’, 1985], are based, then, on a belief in the compatibility of an ideology based on tradition and an economic practice based on modernistaiont. What both fail to account for is th efact that the construction of a cohesive nation-state was often a precondition for the development of industrial capitalism in European history. [...] Furthermore, the Bildungsroman form is one which dramatises on the level of the individual subject the universal narrative of modernity that nationalism proposes at the level of the ethnic group.’ (p.157.) ‘The fact is that Bolger and O’Toole are closer to their Revival antagonists than they think [...] The polemical point is to suggest that modernity in the Republic has been betrayed by nationalism; this forecloses any discussion of the nature of modernisation itself, or of the kind of modernising development initiated by Lemass. This approach, however, is typical of the novel, and of Bolger’s work more generally, which tends to depict the condition of Irish modernity, but not to offer a sustained analysis of it.’ (p.158.)

Further [McCarthy]: ‘But in Bolger’s Ireland, the capacity of the core to exploit the periphery is only to be measured by the extent that the country has succeeded in conquering the city. Thus, Bolger ends up producing a discourse of the countryside that is not, in fact, so far removed from the Revivalists that he so resolutely seems to be turning away from.’ (p.160.) ‘[I]t would seem [...] that neither Bolger nor [Roddy] Doyle, at least partly because of their reaction against an aesthetically radical but apparently institutionalised Modernism, have found a way of avoiding the nets of Romantic Revivalism. Therefore, one is forced to conclude, without wishing to dismiss the movement tout court, that the most prominent figures [of] the “Dublin Renaissance” has yet produced have thus far failed to create a true alternative to the tradition from which they are in flight.’ (p.164.) Further, ‘Bolger’s writing, for all its disavowal of the discourse of the nation, remains as imbricated with that discourse as the literary modes that it sees itself as replacing.’ (p.183.)

Fintan O’Toole, ‘The Former People’, review of The Family on Paradise Pier, in The Guardian (Sat., 7 May 2005): ‘Bolger’s The Family on Paradise Pier draws both on a real family and on recognisable historical characters, including the left-wing agitator Jim Gralton, the Behan family and even, briefly, Charles Haughey. The narrative is partly based on conversations taped by the author in 1992 with Sheila Fitzgerald, then almost 90. Though he changes her first name to Eva, and does likewise with those of her four siblings, he retains their sonorous family name Goold Verschoyle and follows their lives between 1915 and 1946, through the collapse of their world and their attempts, by means of art and politics, to create another. They interact with great events the Irish and Russian revolutions, the British general strike, the Spanish civil war and the second world war but have no real effect on any of them. / Eva does not, as she dreams, become a great painter. The Marxist revolutions that Brendan and Art dream of don’t happen. Brendan disappears into the gulags. The family falls to pieces. Idealism is betrayed, but for Eva especially it is not abandoned. Though the breadth of the canvas does lead to an occasional loss of focus, Bolger nevertheless sustains a remarkably vivid account of the way those who don’t count may nevertheless matter. His best novel since The Journey Home in 1990, it is a moving testament to the ability of the human personality to endure even when the world it inhabits has no great use for it.’

Liam Harte, ‘Tragic Trio Trapped by History: politics is character in family saga set against European upheaval’, review of The Family on Paradise Pier, in The Irish Times, 9 April 2005 ), Weekend, p.12: ‘It is almost 20 years since Dermot Bolger complained about an “idea of nationhood which simply could not contain the Ireland of concrete and dual carriageway (which is as Irish as turf and boreens) that was a reality before our eyes’. Much of his literary output since then, as novelist, poet, playwright and editor, has been devoted to challenging the dominance of this nationalist aesthetic by writing from the perspective of various disenfranchised social groups: emigrants, the suburban working class, the Protestant minority. In the process he has become one of the leading sponsors of a liberal post-nationalism predicated on the need to accommodate the multiple strands of cultural difference and ideological dissent within the “imagined community” of Irishness. / The Family on Paradise Pier shows Bolger extending his critique of the concept of a historic Irish identity through an exploration of the conflicting forms of ideological affiliation and alienation that attended the birth of the State. [...] While, ideologically, the novel resists the notion that history is destiny, it endorses the view that politics is character, and herein lies its central weakness. Bolger’s decision to set his family saga against a swirling canvas of Europe-wide social and political upheaval obliges him to anchor the action in specific times and places throughout. Consequently, historical exposition often gets in the way of subtle characterisation and the dialogue strains under a dense mass of allusions. Only when Bolger’s kaleidoscopic lens settles on a single setting for a concentrated period as happens in Part Two, set in Co May in 1936 - do characters transcend their typicality and grow in intimacy as individuals with complex interior lives. In such moments The Family on Paradise Pier fulfils its ambituious aim of imaginatively recreating defining tensions and tragedies of a family, and a nation, in flux.’ [For full review, see infra.]

Fintan O’Toole, ‘The Former People’, review of Sebastian Barry, A Long Long Way, and Dermot Bolger, The Family on Paradise Pier, in The Guardian (q.d., 2005): ‘[...] Bolger’s The Family on Paradise Pier draws both on a real family and on recognisable historical characters, including the left-wing agitator Jim. Gralton, the Behan family, and even, briefly, Charles Haughey. The narrative is partly based on conversations taped by the author in 1992 with Sheila Fitzgerald, then almost 90. Though he changes her first name to Eva, and does likewise with those of her four siblings, he retains their sonorous family name - Goold Verschoyle -and follows their lives between 1915 and 1946, through the collapse of their world and their attempts, by means of art and politics, to create another. They interact with great events - the Irish and Russian revolutions, the British general strike, the Spanish civilwar and the second world war - but have no real effect on any of them. / Eva does not, as she dreams, become a great painter. The Marxist revolutions that Brendan and Art dream of don’t happen. Brendan disappears into the gulags. The family falls to pieces. Idealism is betrayed, but for Eva especially it is not abandoned. Though the breadth ofthe canvas does lead to an occasional loss of focus, Bolger nevertheless sustains a remarkably vivid account of the way those who don’t count may nevertheless matter. His best novel since The Journey Home in 1990, it is a moving testament to the ability of the human personality to endure even when the world it inhabits has no great use for it.’

Angela M. Cornyn, review of New Town Soul, in Irish Independent (28 Nov. 2010): ‘A derelict house in the affluent suburb of Blackrock on Dublin’s southside, three impressionable teenagers and a strange old man are the stuff of Dermot Bolger’s latest novel New Town Soul, a supernatural thriller for young adults. [...] The old, dilapidated house at the end of Castledawson Avenue and its unexpected inhabitant, an elderly, sick man who seems to have been around forever, become the focal point of the story which unravels for the three teens Shane, Joey and Geraldine. The story hinges on secrets, and the willingness to explore self, relationships, life issues and familiar surroundings. [...] The old man [who lives there] has secrets a-plenty to share with his uninvited visitors, but these secrets come at a very high price, which demands one to gamble or not with one’s soul. If a soul is snatched, then a person becomes “a changeling, someone forced to be part of a chain, after some person or power has snatched their soul”, and is condemned to an everlasting limbo. / So, beware “whatever you do in life, never let anyone snatch your soul”. How does someone snatch a soul? “By making a pact with you; by promising you your heart’s most hidden desire ... Keep your soul safe ... Once it is stolen, it can never truly be your own again.” / New Town Soul is a ghostly thriller situated in the real world of contemporary teenage experience in Ireland.’ (See full-text copy in RICORSO Library, “Criticism > Reviews”, via index, or direct.)

Christina Hunt Mahony, review of The Lonely Sea and the Sky, in The Irish Times (28 May 2016), Weekend Section: ‘Dermot Bolger is a writer not easily categorised, because he has published extensively across genres. He has also played an important role in the history of the small Irish press - first with the establishment of Raven Arts in 1977, and then with New Island, the publisher of his latest work. Impressive as these achievements are, it doesn’t always do for a writer to defy or escape neat categories, because these usually provide the foundation for a reputation. Diffusion of talent can be confused with authorial dabbling or lack of focus. / In his three decades of writing, Bolger has defied the odds to critical acclaim both here and abroad. He is best known to Irish readers as the author of working-class Dublin fiction, but his novels display a broader range than that suggests. Fetishism, criminality, the precarious features of immigrant and emigrant labour and life - it’s all there, interspersed with touching vignettes of young love. / The Lonely Sea and Sky [...] covers territory new for Bolger [being] based on incidents from his father’s life as a merchant sailor out of Wexford. Most of its action takes place outside Ireland, either aboard ship or in foreign ports from Cardiff to Lisbon. More than 100 pages in the midsection are given over to a detailed account of Christmas Eve and Day, 1943, in the Portuguese capital. [...] Bolger gradually fills in the cast of characters Jack comes to know and admire in the intimate world of a vessel described, rather anachronistically, “as long as ten Model T Fords”. There is the dodgy Mossy Tierney, who has promised to act as paterfamilias to young Roche; the terminally ill second mate, Mr Walton; the benign Capt Donovan; and the solitary and silent old salt, Myles Foley. / Much is made of the camaraderie and strong bonds of loyalty among seamen, and, with its emphasis on the long-standing traditions of seafarers, there is a timeless character to the narrative. Indeed, the chosen diction is, at times, older than its 1940s setting warrants. [...]. The Lonely Sea and Sky stands as a war novel with insight into the era and its realities in two very different neutral countries - a distinct contribution to the genre.’ Mahony warns of surprise events at sea on the return journey from Lisbon for which earlier warnings of danger at wartime do not prepare the reader. (See full-text copy in RICORSO Library, “Criticism > Reviews”, via index, or as attached.)

[ top ]

Quotations

The Journey Home (1989): ‘Far below, Dublin was moving towards the violent crescendo of its Friday night, taking to the twentieth century like an aborigine to whiskey. Studded punks pissed openly on corners. Glue sniffers stumbled into each other, coats over their arms as they tried to pick pockets. Addicts stalked rich-looking tourists. Stolen cars zigzagged through the distant grey estates where pensioners prayed anxiously behind bolted doors, listening for the smash of glass. In the new disco bars children were queuing, girls of fourteen shoving their way up for last drinks at the bar. (Quoted in Gerry Smyth, The Novel and the Nation, Pluto 1997, p. 35)’. Further, [Hanno:] ‘I didn’t understand it then, but I grew up in perpetual exile: from my parents when on the streets, from my own world when at home [...] How can you learn self-respect if you’re taught that where you live is not your real home?’ (1991 Edn., p.8; quoted in Conor McCarthy, Modernisation: Crisis and Culture in Ireland 1969-1992, Four Courts 2000, p.153.)

The Journey Home (1989): ‘Woods like this have sheltered us for centuries. After each plantation this is where we came, watched the invader renaming our lands, made raids in the night on what had once been our home. Ribbonmen, Michael Dwyer’s men, Croppies, Irregulars. Each century gave its name to those young men. What will they call us in the future, the tramps, the Gypsies, the enemies of the community that stays put? / I do not expect you to wait for me, Cait. just don’t leave, stand your ground. Tell him about me sometime; teach him the first lesson early on: there is no home, nowhere certain any more. And tell him of Shay, like our parents told us the legends of old; tell him of the one who tried to return to what can never be reclaimed. Describe his face, Cait, the raven black hair, that smile before the car bore down and our new enslavement began. / [...] Sleep on, my love. Tomorrow or the next day they will come. I will keep on running till they kill or catch me. Then it will be your turn and the child inside you. Out there [...] commentators [are] discussing the reaction of the nation [to the election results]. It doesn’t matter to internal exiles like us. No, we’re not exiles, because you are the only nation I give allegiance to now [...] When you hold me, Cait, I have reached home.’ (pp.293-94; McCarthy, pp.163-64; also quotes description of family pub divided between countrymen nursing pints upstairs in the upstairs bar and youngsters rolling joints in the bar below, Bolger, p.32-33; McCarthy, p.156.)

Contemporary Irish Fiction (1992), Introduction: ‘Looking back at the achievements with the short-story form of Frank O’Connor and Sean O’Faolain ... it is hard to know how much they problems of censorship in their own country influenced their bent towards short fiction ... or how much the society they existed in lent itself more readily towards the short story.’ (p. xv); ‘photographing a moving object’ (p.xxvii); ‘The ridiculous academic phrase “Anglo-Irish literature” has helped to reinforce this crippling notion of what constituted Irish literature’; challenging and dissenting young European literature ... in the act of redefining itself and the world around it.’ (p.xxviii).

Inspiration: Bolger gives an account of the inspiration of April Bright (Peacock Aug. 1996), in a collection of letters and papers recovered from a skip where it was deposited by new house-owners, and in his own experience of moving into a previously occupied Dublin terrace house, with its ‘ghosts’. Among the papers were the Catechism Notes of a girl, 1944. Bolger writes, ‘It is a play about the dreams and rivalries between growing sisters, and of how a house can retain a yearning to hear the sounds of a child again. It tries to explore the personal histories that lie buried within every old street, through the unfolding of two sets of ordinary lives, divided by half a century and yet linked by universal hopes and longings; and by a final affirmation that love must be for sickness and for health, for birth and for death - both equally rich parts of the diversity of lives which are pledged together.’ (Sunday Independent, 20 Aug. 1995).

‘A Familiar Setting’, Dermot Bolger gives an account of Kelly’s Hotel, Rosslare, estab. by William J. Kelly in licence of 1893, and his novel Temptation, set there; Alison Gill returns to the hotel with her husband and children as in every year, unaware that the man she almost married 20 years before has done the same with his family during a different week; Bolger began the novel in the week before his twentieth birthday and locked himself away in a remote lighthouse to finish it ‘last year’. (The Irish Times [Weekend], 17 June, 2000, p.4.)

[ top ]

Valparaiso: ‘Dermot Bolger on poetic odysseys’, in ‘Primary Colours’ [“Finishing Lines” column], The Irish Times Magazine, 24 Nov. 2001: Reminisces about primary school experience [in keeping with the series], and recounts the impressions made on him by poems by Patrick Pearse (‘the only person who could compare with Pearse was Christ - but even Christ would have been found lacking’), Ledwidge and Pádraig de Brún (1899-1960): “Tháinig long ó Valparaiso/Scaoileach téad a seol sa chuan/Chuir a hainm dom I gcuimhe/Ríocht na greine, tír na mbua/‘Gluais’, ar sí, ‘ar thuras fada [...]”’. Bolger quotes the translation by Theo Dorgan: ‘A ship came from Valparaiso,/Let go her anchor in the bay,/Her name flashed bright, it brought to mind/A land of plenty, of sun and fame./“Come”, she said, “on a long journey/Away from this land of cloud and mist;/Under the Andes blue-grey slopes/There’s a jewel city, by the sun kissed [...]’. Bolger recounts in the present tense how he has become a guest at the All Hallow’s Seminary in Drumcondra in order to ‘work in a cell’ on ‘the most difficult novel I have ever written.’ He relates the substance: ‘The hero is a compulsive gambler, hopelessly in debt and being made redundant, with his marriage falling apart in 1989, when he takes the ultimate gamble by faking his death in a train crash and disappearing. Alive he feels worthless, but dead - between compensation and insurance - he can finally provide for his family. / He spends a decade fleeing across Europe, haunted by his childhood. But the murder of his father (a planning official due to testify about a crooked politician) brings shadowy danger figures to the surface, leaving his wife and son unknowingly exposed to danger and forcing him to return like a ghost to watch over them. [...] Suddenly I know where my character was heading in his mind when he disappeared. He was seeking the mythical place we all imagined awaited us when we were young, where our lives would be utterly changed. I left the attic knowing my title [...] mesmerised by the lure of Pádraig de Brún’s marvellous words.’ (End; p.82.)

Ireland in Exile (1993), Introduction: ‘[refusal to be] silenced by distance’ (p.10); ‘inconvenient to our fabulous dream of ourselves’ (p.15); ‘commuting emigrants’ (p.7);

“Home for Christmas” ‘“Home for Christmas”, tale of uneasy homecoming, death and revenge’, Sunday Independent (31 Dec. 1995) [Living], 29L: ‘[He] is amongst his family now [..] is a different person from the one I had known there or the one I glimpsed in that hotel in Glasnevin.’ [The story is about a mentally illness.]

Phosphorescent: ‘Let us wake in Leinster Street, / Both of us still twenty six, / On a December morning in 1985 ... When you were still too shy / To dress yourself while I watched / Your limbs garbed in light ... The phosphorescence of our lives / Still glowing with this happiness.’ (“A December Morning in Leinster Street, 1985”; in Sunday Independent, 29 Dec. 1995, “Poems”.)

A novel starts ...: ‘A novel idea: why it was time for a rewrite’, in The Irish Times (18 Sept. 2010), Weekend Review, p.8: ‘A novel starts by being about one thing, but as a citizen you have your antennae open to the discourse occurring within your society. Often, while writing the first draft of A Second Life, when I turned on a radio or overheard conversations on buses, I realised how ever-growing numbers of mothers and children separated during the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s were now desperate to find each other. Despite huge obstacles, people were attempting to take tentative steps towards finding the stranger who was their parent or child, never sure whether such approaches would be welcomed or rebuffed. / Adoption gradually became the novel’s central theme, starting to echo the hidden stories that were finally being told around me. People once silenced by shame were no longer being silenced. Irish society was never ruled by an obsessive devotion to religion; it was ruled by a fetish for respectability, the main facet of which involved hiding family secrets. This wall of silence was finally being eroded by individual voices in 1993 a decade before films such as The Magdalene Sisters but the physical walls behind which the adoption files were kept remained as impenetrable as ever.’ (For full text version, see RICORSO Library, “Authors”, via index, or direct.)

Making sense: ‘I don’t think novelists are obliged to do anything except write novels [...] And I think that there’s a very great danger in seeing novelists as spokespeople for anything other than themselves. The word novelist is a very grand term. I can only talk about myself: for me writing has always been my way of trying to make sense of the physical world around me. And in doing so, hopefully, that world will also make sense to the people who read my books.’ (Quoted in Arminta Wallace, ‘Out with the auld, in with the new’ [on literary Dublin], in The Irish Times (12 March 2011, Weekend, p.1.)

Dublin-ers: ‘I’m like the vast and overwhelming majority of Dubliners in that I don’t have a drop of Dublin blood in me [...] My father is from a family of seven in Wexford town; my mother was from a family of 11 on a small farm in Monaghan. A number of them came to Dublin during the war. Almost all of them had to emigrate.’ This mutability, Bolger adds, is written into the DNA of Dublin. ‘For any city to be a lively, vibrant place it needs to have a perpetual influx of new people coming in with new ideas and new cultures and new influences. Forty years ago that influx was coming from Monaghan and Wexford, and it’s coming from Lithuania and Poland now.’ (Arminta Wallace, idem.)

| Posted on Facebook (10.09.2018) - |

|

| Posted on Facebook (10.09.2018) - |

|

| Note : The messages is illustrated by the cover of Secrets Never Told [2020]; Facebook, 06.08.2020. |

[ top ]

References

Katie Donovan, A. N. Jeffares & Brendan Kennelly, eds., Ireland’s Women (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1994), incls. selection.

| There is a production of “The Parting Glass” by axisBallymun at YouTube [online; accessed 29.06.2011]. |

Colin Smythe (publisher) catalogue lists Bolger, ed., The Dolmen Book of Irish Christmas Stories; Internal Exiles; note also rep. Dermot Bolger, Nightshift (Penguin 1993), 144pp.

[ top ]

| Poems in The Inherited Boundaries: Younger Poets of the Republic of Ireland, ed. Sebastian Barry (Dolmen 1986) | |

|

|

|

101 103 |

|

|

|

106 108 110 |

|

|

|

111 111 |

|

|

|

114 114 115 116 116 117 118 119 |

University of Ulster Library holds The Bright Wave [PB 1353 B9]; Invisible Dublin, ed. Dermot Bolger [TRL 820.8]; Night Shift [JORD 823.91].

[ top ]

Notes

The Lament for Arthur Cleary (1989), adapted for stage by Wet Paint in Project Theatre, 1989; Edinburgh Festival, Arthur Cleary Productions, 1990; BBC Radio 4, 1990; Irish Tour, by Arthur Cleary Prod.; Scottish Tour, by 7: 84; New York, Irish Arts Centre, 1992; Samuel Beckett Award; Stewart Parker Award; BBC Award, and Edinburgh Fringe Theatre Award.

Invisible Dublin: A Journey through Dublin’s Suburbs (1991), is ‘an attempt to chronicle the lives of the new Dubliners in the new Dublin as it has been lived by them’ (Introduction; p.10.)

A Second Life (1994) [Note on new edn.; 2022]: Following a car crash, for several seconds Dublin photographer Sean Blake is clinically dead but finds his progress towards the afterworld blocked by a haunting face he only partially recognises. Restored to a miraculous second chance at life - he feels profoundly changed. He is haunted by not knowing who he truly is because this is not the first time he has been given a second life. At six weeks old he was taken from his birth mother, a young girl forced to give him up for adoption. Now he knows that until he unlocks the truth about his origins, he will be a stranger to his wife, to his children and to himself. Struggling against a wall of official silence and a complex sense of guilt, Sean determines to find his birth mother, embarking on an absorbing journey into archives, memories, dreams and startling confessions. The first modern novel to address the scandal of Irish Magdalene laundries when it was published in 1994, A Second Life continued to haunt Bolger’s imagination. He has never allowed its republication until he felt ready to retell the story in a new and even more compelling way. This reimagined text is therefore neither an old novel nor a new one, but a completely ‘renewed’ novel, that grows towards a spelling-binding, profoundly moving conclusion.

Temptation (2000), novel set in holiday hotel in souther Ireland; Alison Alison Gill, 39, is left alone with the children while her husband Peadar, a school principal, returns to Dublin to deal with a crisis arising from the planned school extension; Chris Conway, her former boyfriend, is coming to terms with the death of his wife and children and staying in the same hotel. Reviewing, Bernice Harrison laments that the central characters are so dreary it’s hard to care whether or not they succomb to any sort of temptation and questions whether the challenge of such a title can be met. (The Irish Times, Paperback notes [q.d.].)

The Lonely Sea and the Sky (2016) [notice to new edn. 2022): Part historical fiction, part extraordinary coming-of-age tale, The Lonely Sea and Sky charts the maiden voyage of fourteen-year-old Jack Roche aboard a tiny Wexford ship, the Kerlogue, on a treacherous wartime journey to Portugal. After his father ’s ship is sunk on this same route, Jack must go to sea to support his family swapping Wexford ’s small streets for Lisbon ’s vibrant boulevards: where every foreigner seems to be a refugee or a spy, and where he falls under the spell of Katerina, a Czech girl surviving on her wits. Based on a real-life rescue in 1943, when the Kerlogue ’s crew risked their lives to save 168 drowning German sailors - members of the same navy that had killed Jack ’s father. Forced to choose who to save and who to leave behind, the Kerlogue grows so dangerously overloaded that no one knows if they will survive amid the massive Biscay waves. A brilliant portrayal of those unarmed Irish ships that sailed alone through hazardous waters; of young romance and a boy encountering a world where every experience is intense and dangerous.

An Ark of Light (2018) - Publisher’s blurp: ‘There is one thing you must never lose sight of. No matter what life deals you, promise me that you will strive tooth and nail for the right to be happy. Having surrendered her happiness to raise her children, Eva Fitzgerald defies convention in 1950s Ireland by leaving a failed marriage to embark on an extraordinary journey of self-discovery. It takes her from teeming Moroccan streets and being flour-bombed in radical marches in London to living in old age in a caravan that becomes an ark for all those whom she befriends amid the fields of Mayo. An indefatigable idealist, Eva strives to forge her identity while entangled in the fault-lines of her children’s unravelling lives. An Ark of Light is a devastating portrayal of a mother’s anxiety for her gay son in a world where homosexuality is illegal and explores a terse relationship between a mother and daughter with nothing in common beyond love. Remarkably affecting and gorgeously rendered, this standalone novel completes the real-life story of the unforgettable heroine of Bolger’s bestselling novel, The Family on Paradise Pier, in following a free spirit trying to hold her family together while striving to be happy. This struggle is often heartbreakingly lost, but Eva never loses her indomitable spirit. A towering achievement by one of Ireland’s best-loved authors about the unshakeable bonds of family, the indestructability of love and the price a woman pays for the right to be herself. (Post by author on Facebook, 22.08.2018.)

Hide Away (2024): Ireland 1941, the post-Civil War code of silence between both sides is barely holding the young state together, across the water Britain is fighting for its very survival. Hidden behind the walls of Grangegorman Mental Hospital, four lives collide. Four lives equally demolished by different wars, different betrayals, different traumas. Gus, a shrewd attendant, is the keeper of everyone’s secrets, especially his own. Two War of Independence veterans are reunited. Jimmy Nolan, has spent twenty years as a psychiatric patient, unable to recover from his involvement in youthful killings. In contrast, Francis Dillon has prospered as a businessman, until rumours of Civil War atrocities cause his collapse, suffering delusions of enemies seeking to kill him. Doctor Fairfax has fled London after his lover’s death, found among the bombed out rubble in the arms of another man. Desperate to rekindle a sense of purpose, Fairfax tries to help Dillon recover by getting him to talk about his past. But a code of silence surrounds the traumatic violence Ireland has endured. Is Dillon willing to break his silence to find a way back to his family? (Publisher’s notice; posted as email 19.08.2024.)

Warp effect: ‘John Walshe, Ed. Corr. of Irish Independent, declares that Paul Durcan’s Raven collection Jesus, Breaks His Fall [sic], should be banned from all schools; Eileen Fox, PRO of CBS Parents Council called it ‘extremely offensive.’ [&c.]. See Bolger gives an account of the founding of Raven Arts, in ‘How Poetry Warps the Mind’, Sunday Independent, Living & Leisure, 9L (8 Dec. 1994).

Northside: New Writers’ Press was initially printed at Dorset Street, Dublin - see Augustus Young, On Loaning Hill (1972) [COPAC ref.].

Ulysses adaptation: ‘In 1994 Dermot Bolger was commissioned by the Rosenbach Museum (which holds Joyce’s original manuscript of Ulysses) to adapt the novel Ulysses for the stage as the centrepiece of Philadelphia’s celebration of the 90th Bloomsday. A Dublin Bloom is the text of that commission, a dramatic dream-like recreation of Mr. Bloom’s journey through that most significant Dublin day. The original production was directed by Greg Doran at the Annenberg Centre, the University of Pennsylvania, USA, on June 16th, 1994.’ (See Dermot Bolger website - Dublin Bloom online; accessed 15.11.2012.)

Cf. Bolger’s Irish Times account of the same transaction: ‘One Monday evening in 1993 the English theatre director Greg Doran, of the Royal Shakespeare Company, phoned to say that he had recently staged Derek Walcott’s acclaimed version of the Odyssey and wanted to follow it with a stage version of James Joyce’s Ulysses. / I explained why I would never attempt this near-impossible task. [...] As Greg departed for London I stood outside the restaurant, feeling palpable terror, because in explaining how it couldn’t be done I had somehow agreed to transpose Joyce’s masterpiece of 265,000 words in 18 episodes, alternating through a dazzling array of linguistic styles into a play, due to have a staged reading in a 1,300-seat Philadelphia theatre the following Bloomsday.’ (‘Staging Ulysses’, in The Irish Times, 17 Oct. 2012, Weekend; for full text version, see Library > Reviews via index or as attached.)

[ top ]