Life

| 1881-1962 [Stephen James Meredith Brown, S.J.]; b. Co. Down; ordained, 1914; resided at the Jesuit House in Milltown, Co. Dublin; estb. the Catholic Library, Dublin; issued Reader’s Guide to Irish Fiction (1910), A Guide to Books on Ireland (1912), and Ireland in Fiction (1919), delegating much of the reading to a friends; Essays, Literary and Religious [q.d.], and also Catalogue of Tales and Novels by Catholic Writers (1927), with numerous edns.; the first edition of Fr. Brown’s Ireland in Fiction (1916) was printed by Maunsel but was destroyed by fire in the 1916 Rising; appeared with some revisions in 1919; |

| delivered ‘We Owe Something to Anglo-Irish Literature’ at UCD Literary & Historical Society, 1939 and subsequently attacked by Stephen Quinn in Catholic Bulletin (‘Sham Literature of the Anglo-Irish’); issued Studies in Life, By and Large (1942) containgin essays such as ‘The Crowd’ and ‘The Message of Poetry’ that show a wide familiarity with literature and ideas; compiled poetry anthologies for Leaving Certificate classes and wrote numerous religious pamphlets, informed by a knowledge of world affairs and occasionally anti-Communist; he was struck by a car outside the British Museum and died soon at Milltown soon after. DIW [IF2] OCIL |

[ top ]

Works| Bibliography & Criticism |

|

| Religion & Commentary |

|

| Articles |

|

| Pamphlets (sel.) |

|

| Miscellaneous |

|

Index of Publications available at Internet Archive with inks supplied by Clare County Library Ireland in Fiction: A Guide to Irish Novels, Tales, Romances, and Folk-lore, by Stephen J. M. Brown [new edn.] (Dublin: Maunsel 1919), 362pp. Available at Internet Archive See also Stephen J. Brown, SJ, ‘Ireland in Books, 1945’ [column], in The Irish Monthly, ed. Fr. Matthew Russell, 74:874 (April 1946), pp.137-47; available at JSTOR - online.]

[ top ]

Bibliographical details

Poetry of Irish History: - viz., Historical Ballad Poetry of Ireland [New and enl. edn., now re-titled Poetry of Irish History], arranged by Mary J. Brown & ed. by Stephen J. Brown (Dublin; Cork: Talbot Press 1927), xviii, 380pp., 8°/19cm.; prev. iss. as Historical Ballad Poetry of Ireland, arranged by M. J. Brown, with an introduction by Stephen J. Brown (Dublin & Belfast: Educational Co. of Ireland 1912), 256pp., ill. [8 ports., incl. front.],, 19cm.; incls. ‘List of authorities consulted for notes’, p.13.Guide to Books on Ireland, edited by Stephen Brown, S.J. author of a Reader’s Guide to Irish Fiction: Part I: FromLilterature, Poetry, Music and Plays (Dublin: Hodges Figgis & Co.; London: Longmans & Green 1912), 371pp. [Index I: General Collections and Selections, [326]ff.; Index II: Prose Literature, [327]ff.; Index III: Poetry, 332ff; Index to Music, IV, 335ff; V: Index to Plays (Titles), 342ff; VI: Index to Plays (Authors), 359ff.; VII: Index to Plays (Subjects), p.367ff.]

CONTENTS: Among the dramatists listed under “Plays before 1700” Joseph Holloway - who contributed that section to Brown’s book - cites the following as representing Irish characters and scenes: 1) The Misfortunes of Arthur, with Irish-dressed chars. as Fury and Revenge; 2) MacMorris in Henry IV, Pt. II; 3) History of Sir John Oldcastle with MacShane of Ulster; 4) John Dekker’s Irish characters; 5) Irish allusions in The White Devil; 6) Heywood’s scenes set in Ireland with kernes. Playwright listed as Irish incl. Henry Burnell (Landgartha); James Shirley (St. Patrick’s Day, 1639). Those cites for the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries are Charles Shadwell (Rotheric O’Connor King of Connaught, or The Distressed Princess, Dublin 1720), The Plotting Lovers or the Dismal Squire (Dublin 1770), and set in Dublin; also Irish Hospitality or Virtue Rewarded (1720); Thomas Shadwell, Teague O’Divelly, The Irish Priest (1682), and 2nd Part (1682); [John] O’Keefe, The Shamrock, or The Anniversary of St. Patrick (Covent Garden 1783), Patrick in Prussia (Dublin 1786), The Poor Soldier, comic op. (Covent Garden 1783), Wicklow Mountains or Gold in Ireland (q.d.), The Lad of the Hills (London 1796), Wicklow Gold Mines, or The Boy from the Scalp, with Tyrone Power as Billy O’Rourke, his 1st apprentice (1830). Other theatrical figures cited are: Richard Head, Susan Centlever, Matthew Concanen, Issac Sparks (actor), George Stevens, John Michelburne, Arthur Murphy, Robert Ashton, Charles Macklin, George Farquhar, R. B. Sheridan, James Sheridan Knowles, Kitty Clive, Richard Cumberland (wrote The West Indian in Ireland), John McDermott, David Garrick (The Irish Widow, London 1772), (-) Kelly (School for Wives, London 1774), Isaac Jackman, Peter Le Fanu (Smock Alley Secrets, Dublin 1778), Mrs. H. Cowley (The Belles’ Stratagem, Dublin 1829), Thomas Knight (The Honest Thieves, Dublin 1843; studied under Macklin acc. ODNB), Walley Chamberlain Oulton (see also ODNB), (-) Holman. J. C. Cross, Daniel O’Meara (Brian Boroimhe, adapted by Knowles), George Colman, Richard Millikin (Darby in Arms, c.1810), Charles Wilson, Mrs Alicia Le Fanu (Sons of Erin), Henry Brereton Code [Cody], Maria Edgworth (Love and Law, et al. printed London 1817), Walter [“Watty”] Cox, James McNeil (The Agent and the Absentee, 1824), William Macready (The Irishman in London, Dublin 1830, with Tyrone Power), John Baldwin Buckstone (The Boyne Water, 1831, et al.; b. London 1802 [ODNB]), Tyrone Power [ODNB “Irish comedian” with 12 titles listed in GBI], William Collier (Kate Kearney, Maid of Killarney), Mrs S. C. Hall (Groves of Blarney 1836, with Tyrone Power), William Bayle Bernard [ODNB: born Boston 1807], H. P. Grattan (The White Boys, London 1836; The Omadhaun, London 1877). [See longer notes in Bibliography > Scholars > Brown - via index., or as attached. (Available at Internet Archive - online.)

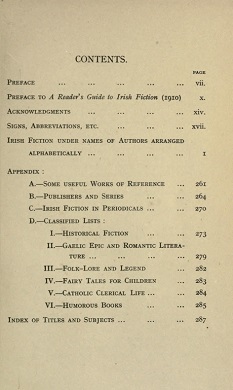

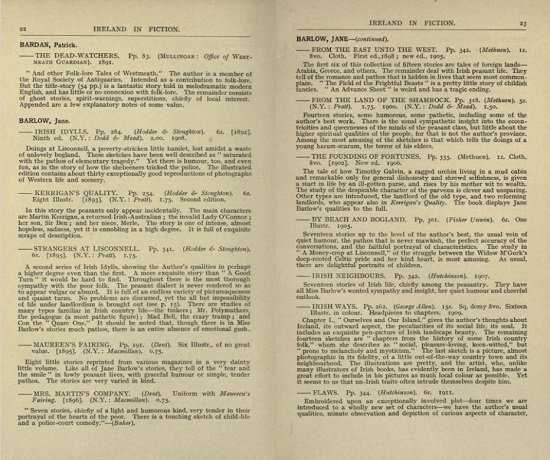

Ireland in Fiction: A Guide to Irish Novels, Tales, Romances and Folklore (Dublin: Maunsel 1919) [Preface dated 1915; Note to New Edition, April 1919, Clongowes Wood, Co. Kildare], and Do. [Burt Franklin Bibliography & Reference Ser., 311; rep. edn.] (NY: Ayer Publishing 1970), 326pp., and Do. [facs. rep.] (Shannon: IUP 1969) - available at Google Books online; accessed 12.02.2012.]

Copy held at Chicago U. (Riverside) - available at Internet Archive [online]; accessed 19.12.2016; another in Toronto UL [online] - both accessed 19.12.2108. —See enlarged version of these images - attached.

Criticism

Publications of Stephen J. Brown (Dublin: Three Candles Press [1955]), prev. printed in An Leabharlann, 8, 4 (1945) pp.141-43.

[ top ]

Commentary

Thomas Flanagan, The Irish Novelists 1800-1850 (Columbia UP 1959), writes in the notes to his Preface: ‘There is [...]a useful bibliographical study: Stephen Brown, S. J. Ireland in Fiction: A Guide to Irish Novels, Tales, Romances, and Folk-Lore (Dublin 1916). Brown brought to his work a long and affectionate familiarity with Irish letters, but his entries should be checked against a more recent and more professional bibliography: L. Leclaire, A General Analytical Bibliography of the Regional Novelists of the British Isles, 1800-1950 (London, 1954).’ (n.5, p.viii.)

Rolf & Magda Loeber, A Guide to Irish Fiction, 1650-1900 (Dublin: Four Courts Press 2006) - Introduction: ‘[...] Ninety years ago, Father Stephen Brown published his seminal Ireland in Fiction (1916, reprinted 1919), which was followed by a second volume, published in 1985, and co-authored by Desmond Clarke. Although pioneering in many respects, as reference sources the volumes are inadequate (incomplete titles abound, first editions are not consistently identified, and many inaccuracies are apparent). Moreover, because of their focus on fiction dealing with the Irish and with Ireland only, the volumes excluded fiction by Irish authors on non-Irish themes, and narrowly evaluated the suitability of fiction for a Roman Catholic readership. Also, Brown’s volumes do not reveal how widely republished Irish fiction was in other cities and countries. [Ftn. An addition problem was that the dating of books by Brown often deviated from that of more certain sources, such as the catalogue of the British Library.] As a result, it is difficult to grasp from them the extent to which the Irish abroad remained in touch with literature from the mother country. / Perhaps most frustratingly, Brown’s bibliographies do not reveal the location of volumes in public repositories. This is all acute problem aggravated by the fact that many of the volumes are very rare.’ (p.xxii.)

J. W. Foster, Irish Novels 1890-1940: New Bearings in Culture and Fiction (Oxford UP 2008), remarks that Brown ‘shares with the Literary Revival an interest only in homeland fiction ... For example, he lists but does not give bibliographical details for or summarise the novels of George Moore set in Ireland’, while ‘in another example (almost at random), Brown gives full details of the Irish novels of M. McDonnell Bodkin but passes over in silence Bodkin’s detective fiction, which is set in England.’ Hence, ‘Brown’s book is a kind of “repatriation” of Irish fiction. Much fiction by Irish authors has been discarded, therefore, which is recoverable only by our reading beyond Brown’s covers.’ (Foster, op. cit., pp.9-10.)

[ top ]

Quotations

Anglo-Irish Literature: In the Preface to A Reader’s Guide to Irish Fiction (1910), Fr. Brown records his hope that the book ‘may be useful to the general reader who wishes to study Ireland’ and also to those buying books for prizes, presents, stocking shops, etc., and further that ‘coming writers of fiction, from seeing what has been done and what has not been done, may get from it some suggestions for future work.’ He finally hopes that ‘it may even help in a small way towards the realisation of a great work not yet attempted, the writing of a history of Anglo-Irish literature.’ (1969 [rep. edn.], p.xv.)

Literary Revival: ‘[...] whatever their literary merits, the claim made for them that they interpreted the Gaelic thought-world, or that the qualities which they contributed to Anglo-Irish literature were authentic Gaelic qualities is quite another thing. One wonders, for instance, if there be anything in common between Mr. Yeats and his shadowy, Celtic dreamland and the flesh and blood Gaels who wrote our Gaelic literature, from the unknown authors of the Táin, through Colmcille, the Medieval bards, Keating and the Munster poets, to Canon Peadar Ó Laoghaire.’ (‘Gaelic & Anglo-Irish - Contacts and Quality’, in The Irish Statesman, 30 Nov. 1929, p.253; quoted in Terence Brown, ‘After the Revival: The Problem of Adequacy and Genre’, in The Genres of Irish Literary Revival, ed. Ronald Schleifer, Oklahoma: Pilgrim; Dublin: Wolfhound 1980, pp.153-78; p.154.)

‘Irish Historical Fiction’ (1916): ‘There are many sad lessons lurking for us in every corner of our history had we but manful courage to face them. Now, I would urge again that one of the best mediums for conveying this lesson, especially to the younger generations and to those whose studies cease with their boyhood, is historical fiction [...]. If there be any truth in these considerations why not see to it that among the works of fiction put into the hands of Irish boys and girls there shall be found some that will imprint in their imagination what of Irish history is best worth remembering, and that will help to fix their affections upon the country whose children they are? How many even to-day are growing among us well-educated in other respects, but knowing nothing about their country. (Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review &c. No. 4, 1915; quoted in James Cahalan, Great Hatred, Little Room: The Irish Historical Novel, Syracuse UP 1983.)

[ top ]

Moral standpoint: in selecting books for Dublin’s Central Catholic Library in the 1930s, Father S.J. Brown admitted that ‘a certain number of novels by Catholic authors have been deliberately omitted as objectionable from the moral standpoint’. (Catalogue of novels and tales by Catholic writers, Dublin 1932, 5th edn), p.v; quoted in Rolf & Magda Loeber, A Guide to Irish Fiction, 1650-1900, Dublin: Four Courts Press 2006, p.lxvi.)

Land League novels: ‘We may omit consideration of the novels that deal with the last named period. They belong to politics rather than to history.’ (Studies, 4, 1915; p.447; quoted in Cahalan, idem.)

Glorious gain: ‘All that is distressing and grievous in life may become for a man so much glorious gain if it draws him away from what is merely outward and passing and throws his mind back on the thought of God’. (Studies in Life, By and Large, 1942). Note that the title-page cites From God to God: An Outline of Life (n.d.) by by the same author but makes no mention of his bibliographical compilations.

[ top ]

British Library holds [1] Historical Ballad Poetry of Ireland. Arranged by M. J. Brown. With an introduction by Stephen J. Brown. [Another copy, with a different titlepage.]. 256pp. Educational Co. of Ireland: Dublin & Belfast, 1912. 8o. Longmans & Co.: London, 1912. 8o. [2] Poetry of Irish History. Edited by Stephen J. Brown. Being a new and enlarged edition of ‘Historical Ballad Poetry of Ireland’ arranged by M. J. Brown. xviii, 380pp. Talbot Press: Dublin & Cork, 1927. 8o. [3: a namesake] [4] A Guide to Books on Ireland. Edited by S. J. Brown ... Part I. Prose Literature, Poetry, Music and Plays. xvii. 371pp. Hodges, Figgis & Co.: Dublin: Longmans & Co.: London, 1912. 8o. [5] A Readers’ Guide to Irish Fiction. [Another copy, with a different titlepage.]. xii, 226pp. Longmans & Co.: London, 1910. 8o. Browne & Nolan: Dublin, 1910. 8o. [6] An Index of Catholic Biographies. xvi, 142pp. Central Catholic Library Association: Dublin, 1930. 8o. [7] An Introduction to Catholic Booklore. vii, 105pp. Burns, Oates & Co.: London, 1933. 8o. [8] Catalogue of Novels and Tales by Catholic Writers ... Fourth edition, revised, &c. Title Fifth edition, revised. Title Sixth edition, revised. xvi, 67pp. Central Catholic Library Association: Dublin, 1930. 8o. xvi, 83pp. Central Catholic Library Association: Dublin, 1932. 8o. 84pp. Burns, Oates & Co.: London, 1935. 8o. [9] Catholic Juvenile Literature. A classified list. Compiled and edited with an introduction by S. J. Brown ... with the assistance of Dermot J. Dargon. 70pp. Burns, Oates & Co.: London, 1935. 8o. [10] Catholic Mission Literature. A handlist. vii, 105pp. Central Catholic Library Association: Dublin, 1932. 8o. [11] Essays of Contention. ix, 213pp. Talbot Press: Dublin, 1954. 8o. [12] France. 32pp. ‘Irish Messenger’: Dublin, 1931. 8o. [13] From God to God. An outline of life. x, 316pp. Brown & Nolan: Dublin, 1940. 8o. [14] From the Realm of Poetry. An anthology for the Leaving Certificate and Matriculation ... examinations. Edited by S. J. Brown. xix, 360pp. Macmillan & Co.: London; Dublin printed, 1946. 8o. [15] God and Ourselves. 24pp. Irish Messenger Office: Dublin, [1931.] 8o. [16] Home to God. 20pp. Irish Messenger Office: Dublin, [1943.] 8o. [17] Image and Truth. Studies in the imagery of the Bible. 161pp. Officium Libri Catholici: Rome, 1955. 8o. [18] In the Byways of Life. ix, 165pp. Talbot Press: Dublin, 1952. 8o. [19] International Index of Catholic Biographies ... 2nd edition, revised and greatly enlarged. xix, 287pp. Burns, Oates & Co.: London, 1935. 8o. [20] Ireland in Fiction. A guide to Irish novels, tales, romances, and folk-lore. Title New edition. xviii, 304pp. Maunsel & Co.: Dublin & London, 1916. 8o. xx, 362pp. Maunsel & Co.: Dublin & London, 1919. 8o. [21] Ireland in fiction. A guide to Irish novels, tales, romances and folklore, &c. Title [Another copy.]. Shannon: Irish University Press, 1969- . 23 cm. [22] Libraries and Literature from a Catholic Standpoint. 323pp. Browne & Nolan: Dublin, 1937. 8o. [23] Our Little Life. 24pp. Irish Messenger Office: Dublin, 1936. 8o. [24] Poison and Balm. [Lectures on Soviet Russia, with special reference to anti-clericalism in that country.]. xiii, 143pp. Browne & Nolan: Dublin, 1938. 8o. [25] Studies in Life, by and large. 243pp. Browne & Nolan: Dublin, 1942. 8o. [26] The Crusade for a Better World [On the work of Riccardo Lombardi, with a summary of his proposals in ‘Per un mondo nuovo.’]. 23pp. ‘Irish Messenger’ Office: Dublin, [1956.] 8o. [27] The Divine Song-Book. A brief induction to the Psalms. 83pp. Sands & Co.: London, 1926. 8o. [28] The Preacher’s Library. xii, 129pp. Sheed & Ward: London, [1928.] 8o. [29] The Press in Ireland. A survey and a guide. xi, 304pp. Browne & Nolan: Dublin, 1937. 8o. [30] The Question of Irish Nationality. (Reprinted from “Studies”.). 43pp. Sealy, Bryers & Walker: Dublin, 1913. 8o. [31] The Realm of Poetry. An introduction. 220pp. G. G. Harrap & Co.: London, 1921. 8o. [32] The World of Imagery, &c. vi, 352pp. Kegan Paul & Co.: London, 1927. 8o. [33] Towards the Realization of God. viii, 180pp. Browne & Nolan: Dublin, 1944. 8o. [34] What Christ means to us. 23pp. Irish Messenger Office: Dublin, [1932.] 8o. [35] What the Church means to us. 24pp. Irish Messenger Office: Dublin, [1934.] 8o. [36] A Survey of Catholic Literature. ix, 249pp. Bruce Publishing Co.: Milwaukee, [1945.] 8o. [37] [La Société internationale.] International Relations from a Catholic standpoint. [Edited by Eugène Beaupin.] Translated from the French. Edited [i.e. the translation edited] ... by Stephen J. Brown. xv, 199pp. Browne & Nolan: Dublin, 1932. 8o. [38] The International Organisation of Labour. [Translated by Stephen J. Brown.] [39] The Central Catholic Library. The first ten years of an Irish enterprise. By the Hon. Librarian [Stephen J. Brown], &c. 79pp. Dublin, 1932. 8o.

Belfast Central Library holds Studies in Life, By and Large (1942). Belfast Linenhall holds Irish Historical Fiction (n.d.)

[ top ]

Notes

Poetry of Irish History (Dublin: Talbot 1927) is an anthology divided by historical ‘periods’ (First Period ... Fifth Period’) including lesser sections such as ‘Ireland Beyond the Seas’, and ‘Love Thou Thy Land’ - the latter opening with “The Green Hills of Erin” by Donnchadh Mac Conmara. The anthology is replete with patriotic poems by Davis, Stephen Gwynn and others. (Copy held in Morris Collection of the University of Ulster Library.)

The Irish language: ‘one of the many anomalies produced by the historic causes that have all but destroyed the Irish language as the living speech of Ireland’ (Preface, Ireland in Fiction 1919; facs. rep. 1969, p.xii, apologising for the absence of books in Irish from the earlier Guide to Fiction (1912).

Desmond Clarke supplies a note on Brown in the foreword of Ireland in Fiction [Pt. I] (1919) and another in the preface to Ireland in Fictioni [Pt II] (1985) remarking that his precedessor received fatal injuries in old age when knocked over by a car outside the British Museum while working on the second edition and died ‘at his beloved Milltown Park.’ (Brown’s own preface to the first volume is addressed Clongowes Wood.)

Seán O’Faolain calls John Banim’s Father Connell ‘one of the earliest novels dealing with priests sympathetically’. He adds on his own account: ‘I find it rather sentimental. Others have approved of it wholeheartedly’, and quotes Stephen Brown: ‘The character is one of the noblest in fiction. He is the ideal Irish priest, almost childlike in simplicity, pious, lavishly charitable, meek and long-suffering but terrible when roused to action’. Note that O’Faolain has taken up the conjectural date 1840 from Brown [err. for 1842].

Dublin memory recalls a young man who had courted Fr. Brown’s cousin Maddy Ross, latter a member of Women Writers’ Club; and had subsequently gone to India - after which silence. On discovering a bundle of letters in a drawer on the death of her mother (with whom she had remained while she lived), the girl finds proposals of marriage from her soldier in them.

Namesake: See The International Organisation of Labour, trans. by Stephen J. Brown (q.d.);

[ top ]