|

|

||

|

|||

Life

| (1729-97; var. 1730 OS], b. 12 Jan., 12 Arran Quay, Dublin [or Ballywater, Shanballymore, home of James Nagle]; second son of fifteen children to Richard Burke, a Dublin attorney who appears to have conformed to Anglicanism to practice law, and Mary Nagle (c.1702–70), of Ballyduff [home of her f. Patrick Nagle]; baptised into the Church of Ireland [i.e., Church of England in Ireland]; entered TCD, 1743; fnd. The Club [later Historical Soc.], with William Dennis, Andrew Buck, Richard Shackleton, Matthew Mohun, Joseph Hamilton and Abraham Ardesoif, 21 April 1747; rejected Buck’s suggestion that ad hominem be avoided as tending to ‘reduce our speeches to dry logical reasoning’; fnd., with others, The Reformer (28 Jan.-21 April 1748; 13 issues; of which there is a unique series in the Pearse St. Public Library); probably affected by Black Dog [Newgate] riot in Dublin, occasioning reflections on the sublimity of crowd uproar; grad. BA, Jan. 1748; Middle Temple, London 1749-50; lodged in Croydon with the father of William Burke, a kinsman [cousin] with whom he collaborated on Account of the European Settlements in Americ, and who was a constant member of Burke’s household perpetually thereafter; experienced poor health; travelled west of England and to France; allowance discontinued by father for neglect of studies; A Vindication of Natural Society (1756), contra Bolingbroke but proceeding as an imitation and extension of the argument ad absurdum to the destruction of state institutions as well as religion, requiring Burke to profess in the second edition that it was in fact a satire on the atheistic rationalism of the Bolingbroke; m. Jane Mary Nugent (1734–1812), dg. of his friend the Catholic physician Christopher Nugent - an Irishman who had treated him at Bath and who had himself married a Presbyterian under the Anglican rite, and was for a time dependent on father-in-law for support, 12 March 1757; enjoyed long and happy marriage with JN (‘In all the anxious moments of my public life, every care vanishes when I enter my own house.’); a son, Richard, b. 9 Feb. 1758; another, Christopher, died in infancy; | |

|

|

| applied unsuccessfully for consulship in Madrid, 1759; edited [viz., ‘conductor’ of] Annual Register for James & Robert Dodsley (London), starting with a contract signed on 24 April 1758 and commencing that year with “The History of the Present War” - being the Seven Years War, 1756-63 - in its pages (but originally as “A View of the History, Politicks and Literature of the Year ...”); edited the journal single-handedly up to 1765, when he entered Parliament; thereafter assisted by Thomas English, and continuing his own contributions up to 1788; appt. priv. sec. to William Gerard Hamilton [“Single-speech Hamilton”], 1759-64; when Hamilton was appt. as Lord Lieutenant, Burke accompanied him to Ireland, 1761-62 and again in 1763-64; wrote, but left unpublished, “Fragment of a Tract on the Popery Laws” - ‘stating the popery laws in general as one leading cause for the imbecility of the country’ [1763] - afterwards pub. in the Coll. Works, Vol. V, 1826 as Tracts Relative to the Laws Against Popery in Ireland and rep. by Matthew Arnold in his Letters, Speeches and Tracts of Edmund Burke on Irish Affairs (Macmillan 1881); resigned a pension obtained for him by Hamilton, remaining as his secretary to the end of 1764; fnd. the Literary Club, with Johnson, Reynolds, et al., 1764; appt. priv. sec. to the PM Lord Rockingham [Charles Watson-Wentworth, 2nd Marquess of Rockingham; Baron and Earl of Malton; 1730-82], July 1765, and remained friends to his death [when his titles became extinct and his estates passed to the 4th Earl Fitzwilliam]; | |

| inherited a small Irish estate, 1765, sold in 1790 [for less than £4,000]; became MP for Wendover [a pocket borough in the gift of Lord Fermanagh, later Earl of Verney], 1765-74; maiden speech, on American question, 27 Jan 1766 (‘spoken in such a manner as to stop the mouths of all Europe’, acc. to Pitt); visited Ireland, 1766; attacked Chatham-Grattan administration esp. on East Indian Co., 1766 (Chatham being the ennobled Pitt), and American question, 1767; participated in stock-jobbing with his brother, and his kinsman, together with Lord Verney (who secured Wendover for him); [marginally] involved in their financial crash, 1769; bought Gregories, a small estate at Beaconsfield in Buckinghamshire, for £20,000, feeding suspicions of corruption, 1768 [Burke to Shackleton: ‘As to myself ... I have made a push with all I could collect of my own, and the aid of friends, to cast a little root in this country’ (1 May 1768)]; effected transfer of Sebright [var. Seabright] Irish MSS to Trinity where Dr. Leland was among those who examined them, 1769; attacked Tories, 1769, spoke his Thoughts on the Present Discontents, in the Commons, 23 April 1770, attributing the discontents to the ‘secret influence [of the] king’s friends’; the same issued as Whig party pamphlet; secured publicity for proceedings of Parliament, 1771; agent for New York province, 1771; assailed under suspicion of being “Junius” (actually Sir Philip Francis), 1772; voted for removal of disabilities on dissenters, and objected to taxation of absentees, 1773; visited Paris, Feb.-Mar. 1773; | |

| joined Fox in attacks on Lord North, 1774-75; MP for Bristol, 1774-78 on invitation of citizens, who were afterwards offended by his championship of free trade and Catholic emancipation; spoke in Commons advocating peace with America (Speech on Conciliation with America, 22 March 1775; pub. May 1775); supported Thomas Townshend when he argued for Catholic Relief in House of Common, 7 April 1777, productive of two relief measures being passed and approved by June 1777; speech against employment of Indians in America War, Feb. 1778; Catholic Committee, Dublin, votes 500 guineas award to Burke, 11 Nov. 1778, which the latter refused and returned when forwarded to him (with suggestion that it be used to educate Catholics barred from Irish schools); suggested measures of Catholic relief to Sir George Savile; helped Admiral Keppel in successful defence against court-martial, 1779; advocated economic reform in public service (speech on Economical Reformation of the Civil and Other Establishments, 11 Feb. 1780), and supported Wilberforce Anti-slavery Act, 1780; made his Speech at the Guildhall in Bristol (1780), vindicating his parliamentary representation of the city [as one of three seat-holders] and addressing the electors on the affairs of America and Ireland (‘stupidity has lost America; stupidity will lose us Ireland’); | |

|

|

| wrote Thoughts on the Approaching Executions in the wake of the Gordon Riots, London (June 1780), advocating execution of the six sentenced men in six different places; stood in danger of Protestant backlash; elected MP for Malton, Yorkshire, 1781-84 through Rockingham’s influence [i.e., a pocket borough in his gift]; his attacks on North forced the PM’s resignation, 1781-82; appt. Privy Councillor and Paymaster of the Forces and privy counseller, though without a cabinet seat on the Whigs coming to power, March-July 1782; removed 134 sincecures while in office; moderately supported legislative independence for Ireland, 1782 - i.e., commercial and civil self-government for Ireland, with its promise of a ‘natural, cheerful alliance’ of the countries; lost his post with the death of Buckingham and arrival of Lord Shelburne; addressed his Letter from a Distinguished Commoner to a Peer of Ireland on the Penal Laws (1782; pub. 1783) on the Gardiner Catholic Relief Act to Lord Kenmare [Thomas Browne]; , resumed salary as paymaster of forces under it with the formation of Lord North’s coalition with the Duke of Portland, whose cabinet included Charles Fox, Feb. 1783; went into opposition after the fall of the coalition, late 1783, and there remained for the remainder of his career; | |

| joined a committee investigating the East India Co., writing the 9th Report on the system of Warren Hastings in Bengal, and the 11th Report on the system of presents; drafted the Government East India Bill, 1783; spoke on Fox’s India Bill, 1 Dec. 1783 (pub. 22 Jan. 1784), dilating on violent oppressions committed by Wazir’s revenue collectors; appt. rector of Glasgow University, 1784-85; continued attacks on Hastings, and travelled to Scotland, 1785; joined Sir Philip Francis [presumed to be “Junius”] in urging the impeachment of Warren Hastings on charges of embezzlement, fraud, abuse of power, and cruelty; impeachment of Hastings, 10 May 1787; gave a 4-day speech at the opening session, Westminster Hall, Feb. 1788; excluded from Fox’s opposition cabinet, 1788; joined Fox in defending the rights of the Regent, 1788; continued his support for Wilberforce against slavery, 1788-89; spoke in parliament against French democracy, Feb. 1790; | |

| issued Reflections on the French Revolution, 1 Nov. 1790, written in answer to a sermon by a leading dissenter and anti-monarchist Dr. Richard Price at Old Jewry, London (4 Nov., 1789) [see note], and composed in form of letter to Charles-Jean-François Dupont who had sought Burke’s opinion the Flight to Varennes (5-6 Oct. 1790) which had just transpired; accuses Rousseau’s followers of ‘an unjustifiable poetic licence’ in translating into the practical sphere ‘the metaphysically true […] but morally and politically false’ (p.153-54), thus perverting human feeling and engaging in a ‘war with heaven itself’; estranged from Fox and Sheridan due to their initial support for the French Jacobins whom he described as ‘turbulent, discontented men [who] generally despised their own order’; prevailed new Parliament to continue impeachment of Hastings, 1790; made breach with Fox in Parliament, contrary to the latter’s insistence that their differences implied ‘no loss of friendship’, invoking Burke’s reply, ‘I regret to say there is’ (Debate on Quebec Bill, 6 May, 1791); issued Appeal from the New to the Old Whigs (Aug. 1791), arguing that the principles of the French Revolution were antipathetic to those of the Whigs; | |

|

|

| received hon. degree from Dublin Univ. (LLD TCD), 1791; issued Letter to a Member of the National Asssemby (1791), in response to request from François-Louis-Thibault de Menonville for more of his ‘very refreshing mental food’ in a letter of Nov. 1790 [viz., the Reflections] - which included an attack on Jean-Jacques Rousseau as ‘a lover of his kind, but a hater of his kindred’; voted against reform of disabilities against Unitarians and against parliamentary reform; pleaded for war with France and advised support of Pitt and the Tories, quarrelling openly with ministerial party, 1792; his letters to Sir Hercules Langrishe of Jan. 1792 (London; publ. in Dublin, March 1792) reveal the extent of his concern for Irish Catholics; his conversation with Pitt and the memorandum of same, swayed Government policy towards concessions to the Irish Catholics; in the famous ‘dagger speech’ of 21 Dec. 1792 he objected to sequestration of aliens in England; wrote Letter to a Peer of Ireland [Lord Kenmare] on Irish Catholics (1793); continued his quarrel with Fox and Sheridan, 1794; nine-days’ speech in reply to Hasting’s defence, 1794; retired from parliament, July, 1794; pensioned by coalition ministry of Portland Whigs and Pitt, 1794; Fitzwilliam offers Burke’s vacated seat of Malton to his son Richard; Richard d., from consumption, 2 Aug.; | |

| arrival of Lord Fitzwilliam, friend of Burke and Grattan, in Dublin as Viceroy, with imminent promise of Catholic Emancipation, 4 Jan. 1795; Fitzwilliam recalled from Ireland, end of Feb., at behest of Dublin ‘junto’ [Burke’s usage; commonly ‘junta’] led by Fitzgibbon and Beresford; present at acquittal of Hastings, 1795; encouraged foundation of Maynooth College, est. 1795, during viceroyalty of Camden; established school for sons of French emigrés families, Penn, Buckinghamshire, 1796; Thoughts on the Prospect of a Regicide Peace, 26 Oct. 1796 [two, with two others in 1797]; Collected Works (1792-1827), commenced in Burke’s lifetime by French Laurence and Walker King (who later acted as his literary executors); voted for Wilberforce’s anti-slavery laws; travelled to Bath on medical advice, March 1797, occupying No. 11, N. Parade (where Goldsmith also stayed); | |

| d. 9 July and was reported in Watty Cox’s Asylum to have received the last rites from ‘the president of Maynooth’ (Rev. Thomas Hussey); and lives by J. Prior (1824), J. Morley (1897); and [Philip] Magnus (1939), and others; Lord Inchiquin [O’Brien] wrote: ‘he was admired by everybody but had no friends’; he was one of the earliest parliamentarians to address the House of Commons wearing glasses; he also had a brogue which was an object of derision in Parliament. RR ODNB DIB DIW DIL OCEL FDA RAF JMC ODQ OCIL | |

|

|

| [ Burke’s Life & Works: A Short Biography - as attached. ] | |

|

|

[ top ]

Works

See separate file [infra].

Criticism

See separate file [infra].

Commentary

See separate file [infra].

Quotations

See separate file [infra].

[ top ]

| Richard Ryan, Biographia Hibernica: Irish Worthies, Vol. I [of 2] (London & Dublin 1819), pp.251-70 |

| "Edmund Burke" [extract] |

[...] We have now arrived at the last and most important era of the life of Burke, when at once dissolving almost every connection of his former life, he threw himself into the arms of those whom he had uniformly and vehemently opposed. The revolution which was taking place in France was hailed by Fox as the dawn of returning liberty and justice, while Burke regarded it as the meteoric glare of anarchy and ruin. In a debate on the army estimates for 1790, adverting to the revolution in France, Fox considered that event as a reason for rendering a smaller military establishment necessary on our part: “The new form,” he said, “that the government of France was likely to assume, would, he was persuaded, make her a better neighbour, and less propense to hostility, than when she was subject to the cabal and intrigues of ambitious and interested statesmen.” . Burke soon after delivered his sentiments on the subject. Fully coinciding with Fox respecting the evils of the old despotism, and the dangers that accrued from it to this country, he thought very differently of the tranquillity to neighbours and happiness to themselves, likely to ensue from the late proceedings in France. Warming, as he advanced in the argument, he observed, “In the last age we had been in danger of being entangled, by the example of France, in the net of relentless despotism. Our present danger, from the model of a people whose character knew no medium, was that of being led through an admiration of successful fraud and violence, to imitate the excesses of an irrational, unprincipled, proscribing, confiscating, plundering, ferocious, bloody, and tyrannical democracy.” Sheridan expressed his disapprobation of the remarks {263} and reasonings of Burke on this subject, with much force. He thought them quite inconsistent with the general principles and conduct of one who so highly valued the British government and revolution: “The National Assembly,” he said, “had exerted a firmness and perseverance, hitherto unexampled, that had secured the liberty of France, and vindicated the cause of mankind. What action of theirs authorised the appellation of a bloody, ferocious, and tyrannical democracy?” Burke, perceiving Sheridan’s view of affairs in France, differed entirely from him, and thinking his friend’s construction of his observations uncandid, declared, that Mr. Sheridan and he were from that moment separated for ever in politics. “Mr. Sheridan,” he said, “has sacrificed my friendship in exchange for the applause of clubs and associations: I assure him he will find the acquisition too insignificant to be worth the price at which it is purchased.” The sentiments and opinions declared in the house of commons by Messrs. Fox and Sheridan, induced Burke to publish his “Reflections on the French Revolution,” in a more enlarged form, and more closely to contemplate its probable influence on British minds. To account for his apparent change of opinion on the subject of civil liberty, he informs us in his Reflections, that he was endeavouring to “preserve consistency by varying his means to secure the unity of his end; and when the equipoise of the vessel in which he sails, may be in danger of overloading upon one side, is desirous of carrying the small eae of his reasons to that which may preserve the equipoise.” In the session of 1790, he adhered uniformly to the sentiments which he had avowed in his discussions with Fox and Sheridan, identifying the whole body of the dissenters with Drs. Priestley and Price, and therefore looking upon them as the friends of the French revolution and the propagators of its principles in this country. He opposed a motion for the repeal of the test act, a measure which he had, at a former period, strenuously advocated, {264} He also opposed a motion for reform in parliament. At this time Mr. Fox and he still continued in terms of friendship, though they did not frequently meet; but when, in 1791, a bill was proposed for the formation of a constitution in Canada, Burke, in the course of the discussion, entered on the general principle of the rights of man, proceeded to its offspring the constitution of France, and expressed his conviction, that there was a design formed in this country against its constitution. After some of the members of his own party had called Mr. Burke to order, Mr. Fox spoke, and, after declaring his conviction, that the British constitution, though defective in theory, was in practice excellently adapted to this country, repeated his praises of the French revolution, which, he thought, on the whole, one of the most glorious events in the history of mankind. He then proceeded to express his dissent from Burke’s opinions on the subject, as inconsistent with just views of the inherent rights of mankind. These besides, he said, were inconsistent with Mr. Burke’s former principles. Burke, in reply, complained of having been treated by Fox with harshness and malignity; and, after defending his opinions with regard to the new system pursued in France, denied the charge of inconsistency, and insisted that his opinions on government had been the same during all his political life, He said that Mr. Fox and he had often differed, and there had been no loss of friendship between them, but-there is something in the cursed French revolution that envenoms every thing. Fox whispered, “there is no loss of friendship between us.” Burke, with great warmth, answered, “There is! I know the price of my conduct; our friendship is at an end.” Mr. Fox was very greatly agitated by this renunciation of friendship, and made many concessions, but still maintained that Burke had formerly held very different principles, and that he himself had learned from him those principles which he now reprobated, at the same time enforcing the allega{265}tion, by references to measures which Burke had either proposed or promoted, and by many apposite quotations from his speeches. This repetition of the charge of inconsistency prevented the impression which his affectionate and conciliating language and behaviour might otherwise have made on Burke, “It would be. difficult,” says Dr. Bisset, “to determine with certainty whether. constitutional irritability or public principle was the chief cause of Burke’s sacrifice of that friendship which he had so Jong cherished, and of which the talents and qualifications of its object rendered him so worthy.” Another reason has been assigned, which might, perhaps, have had some weight in this determination. It is stated, that an observation of Fox, on the “Reflections,” that they were rather to be regarded-as an effusion of poetic genius, than a philosophical investigation, had reached Burke’s ears; a remark which mortified him as an author, and displeased him asa friend. Be this as it may, from the time of this debate, he remained at complete variance with Mr. Fox, and even treated him with great asperity in some of his subsequent publications. Some days after this discussion, the following paragraph appeared in the Morning Chronicle: “The great and firm body of the Whigs of England have decided on the dispute between Mr. Fox and Mr. Burke; and the former is declared to have maintained the pure doctrines by which they are bound together, and upon which they have invariably acted. The consequence is, that Mr. Burke retires from parliament.” After this consignation to retirement, Mr. Burke no longer took any prominent part in the proceedings of parliament, except with regard to the French revolution and the prosecution of Hastings, which being terminated by the acquittal of that gentleman in the summer of 1794, he soon after resigned his seat, and retired to his villa at Beaconsfield, where, on the 2nd of August in the same year, he met with a severe domestic calamity, in the death of his only.son. In the beginning of the year he {266} also lost his brother Richard; but though this reiterated stroke of death deeply affected him, it neither relaxed the vigour of his mind, nor lessened the interest which he took in public affairs. (pp.262-65.) |

| See full copy in RICORSO > Library > Criticism > History > Legacy - via index, or as attached. |

Justin McCarthy, ed., Irish Literature (Washington 1904), extracts incl. ‘Some Wise and Witty Sayings of Burke’, incl. the phrase ‘the little platoon to which we belong’.

D. J. O’Donoghue, Poets of Ireland (Dublin 1912), notices that ‘Prior quotes a couple of pieces, by one of which Burke is represented in Joshua Edkins’s Collection of Poems, 2 vols. (Dublin 1789-90)’, and supplies a brief biographical note: ‘Born on Arran Quay, Dublin, January 1, 1730, being the son of an attorney. Educated chiefly by Richard Shackleton, of Ballinore, Co. Kildare, but afterwards entered Trinity College, Dublin, where he did not distinguish himself greatly. Graduated B.A. in 1748 and in 1750 settled in London. Entered Parliament in 1766 as M.P. for Wendover’ - ending: ‘His subsequent career needs no detailed record here. Suffice it to say that he died at his country seat, Beaoonsfield, on July 9, 1797, and is buried there.’ (Poets of Ireland, p.47.)

Seamus Deane, ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 1, selects from Sublime and Beautiful; Tracts Relative to the Laws against Popery [var. ‘Fragments of a Tract on the Popery Laws’, prob. written 1761 - acc. Cone; op. cit., supra, p.43 - but dated 1763]; Resolutions for Conciliation; Letter to a Peer; Reflections; 1st Letter to Sir Hercules Langrishe; Letter to Richard Burke; 2nd Letter to Sir Hercules Langrishe; Letter to Thomas Hussey. FDA BIOG, Helped fnd. TCD College Historical Society, grad. 1749 [err.]; Middle Temple, 1750; m. Jane Nugent; in Dublin 1759-64 as secretary to Irish chief Secretary; Rockingham’s sec., 1765; orig. member of Johnson’s Literary Club; shocked by atheism and licentiousness of French intellectuals, 1773; engaged in impeachment of Warren Hastings, 1788-95; with the outbreak of the French Revolution he began his last great campaign, earning a European reputation and irrevocably splitting the Whigs. Bibl. of Works incl. A Vindication of Natural Society (1756); Philosophical Enquiry into the Origins of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1756, enl. 1757); An Account of the European Settlements in America (1757); Thoughts on the Causes of the Present Discontents (1770); Speech on American Taxation (1774); Speech on Conciliation with American (1775, 1778); Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790); Appeal from the Old to the New Whigs (1791); Speeches on the Impeachment of Warren Hastings, in introduction (1792); Writings on Ireland collected by Matthew Arnold, ed., as Edmund Burke on Irish Affairs (Macmillan 1881) [see Conor Cruise O’Brien, reissue, 1988 supra]; also TW Copeland et al., eds., The Correspondence of Edmund Burke, 10 vols. (Cambridge UP and Chicago UP, 1958-71) [vols. 8 and 9 ed. by RB McDowell, the latter with JA Woods] [also cited in Stanford 1984]; The Works of Edmund Burke, 8 vols. (London: Bohn’s Brit. Classics 1854-89); The Works of Edmund Burke, rev. ed. 12 vols. (Little, Brown, Boston 1865-67). NOTE that Kevin Whelan characterises the extracts in The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writingas a ‘superb distillation’, in Kevin Whelan, ‘The bases of Regionalism’, in Prionsias Ó Drisceoil, ed., Culture in Ireland - Regions: Identity and Power (Belfast: QUB/IIS 1993), p.59 [ftn. 13; to text p.13.]

A. N. Jeffares & Peter Van de Kamp, eds., Irish Literature: The Eighteenth Century - An Annotated Anthology, Dublin: IAP 2006, give extracts from A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful [232]; from Reflections on the Revolution in France [237]; from A Letter to a Noble Lord [241-44].

[ top ]

Libraries & Booksellers

See an extensive listing of digital editions of Burke’s works on several major websites — attached — [ This file is part of the Bibliographical Appendix and opens in a separate window. ]

Cathach Books Catalogue (1996-97) lists R. W. Copeland & M. S. Smith, A Checklist of the Correspondence of Edmund Burke (Index Soc. 1955) [Whelan Cat. 32]. A Letter from the Late Rt. Hon. Edmund Bure to a Noble Lord on the attacks made upon him and his Person [sic] ... by Duke of Beford and the Earl of Lauderdale, 1796, new edn. (London; Rivington 1831), 59pp.; A Letter from the Right Hon. Edmund Burke to his Grace the Duke of Portland on the Conduct of the Minority in Parliament, containgin 54 Articles of Impeachment against the Rt. Hon. C. J. Fox (London: Owen 1797), 94pp.; A Letter to the Duke of Grafton with notes; to which is annexed a Complete Exculpation of M. de la Fayette from the Charges indecently urged against him by Mr. Burke, in the House of Commons, in 17th March 1794 (Dublin: Wogan 1794).

Hyland Catalogue (1997) lists Speeches at his Arrival at Bristol and at the Conclusion of the Poll [1st ed.] (1774), 16pp., [Todd 23a]; A Speech of Edmund Burke [...] Guildhall in Bristol (1780), 68pp. [Todd. 39b]; Substance of the Speech [...] in the House of Commons, 23rd May 1794 (1794), 26+6pp. [Todd 64b]; A Philosophical Inquiry [...] into Sublime and Beautiful (London: Tegg 1810) [Todd 5x.]; Burke: Reflections on the Revolution in France (London 1824), xiv+344pp., port. [6mo.; earlier printing of Todd 53nn]; Morley ed., Edmund Burke: Two Speeches on Conciliation with America and Two Letters on Irish Questions (1886); Sir Philip Magnus, ed., Selected Prose of Edmund Burke [1st ed.] (1948); John Morley: Edmund Burke [Definitive Revised edition, 1921] (1923); William O’Brien, Edmund Burke as an Irishman [1st ed.] (1924).

Kenny’s Bookshop (Pamph. Cat. 2001) lists A LETTER FROM MR. BURKE. To A Member Of The National Assembly; In Answer To Some Objections To His Book On French Affairs. Paris, Printed. Dublin: Reprinted by William Porter, 1791. Rebound in Modern Board. Bumped. Foxing throughout. 60pp. €135.00; A LETTER FROM RICHARD BURKE. To Esq. Of Cork. In which the legality and propriety of the meeting recommended in Mr. Byrne’s Circular Letter are discussed. Together with some observations on a measure proposed by a friend to be substituted in the place of The Catholic Committee. Dublin: Printed by P. Byrne, 1792. 1/4 Leather with Cloth Board. Gilt lettering to spine. Foxing throughout. 46pp. €125.00; A LETTER FROM THE RT. HONOURABLE EDMUND BURKE. To His Grace The Duke of Portland, On The Conduct of the Minority in Parliament. Containing Fifty-Four Articles of Impeachment Against The Rt. Hon. C. F. Fox. From the Original Copy, in the Possession of The Noble Duke. London: Printed for the Editor, 1797. 1/4 Leather with Cloth Board. Gilt lettering to spine. Foxing throughout. Uncut. 94pp. €135.00. Do (2002) lists SPEECH OF EDMUND BURKE. Member of Parliament for the City of Bristol. On Presenting to the House of Commons (On the 11th February, 1780). A plan for the better security of the Independence of Parliament and the Oeconomical Reformation of the Civil and Other Establishments. Dublin: Printed by R. Marchbank, for the Company of Booksellers, 1780. Rebound in Modern Board. Title on spine. Foxing throughout. 95pp. [€135]; THE DUKE OF BEDFORD & THE EARL OF LAUDERDALE. A Letter From The Right Honourable Edmund Burke To A Noble Lord, On The Attacks Made Upon Him and His Pension, In The House of Lords. Early In The Present Sessions of Parliament. London: Printed For J. Owen, 1796. Rebound in Modern Board. Waterstained and some holes in the pages. Cloth stamp with gilt lettering to front board. 80pp. [€65.00], and do., Modern Marble Boards. Leather stamp on front cover with gilt lettering.. 80pp. [€165.00].

Ulster Univ. Library (Morris Collection) holds Selections from the Speeches and Writings (1893); The Works of the Rt. Hon. Edmund Burke, 8 vols. (Rivington 1803). [Note: Prior also wrote a life of Edmund Malone.] LIB HB also holds [Arnold, ed.,] Edmund Burke, Irish Affairs [new edn.] (Dublin 1886).

[ top ]

Notes

United Irishmen: The United Irishmen delighted to employ Burke’s disparaging phrase, ‘the swinish multitude’ in referring ironically to themselves. (See Mary Helen Thuente, ‘William Sampson, … &c’, under Sampson, infra.). Note however that the actual phrase he used reads, ‘a [sic] swinish multitude’. Note also that Lady Morgan employs the phrase in The O’Briens and the O’Flaherties [see FDA2 871].

|

|

|

|

||

The Annual Register, briefly edited by Burke, was subtitled ‘a view of the history, politics, and literature for the year’ and published by Robert Dodsley (London). It was acquired and published by Otridge (1791-1812), a continuation being published by Rivington (1820-24), and finally united. See Lowndes, Bibliographical Manual, Vol. I; also QUB Library Catalogue. Note that Deane Swift’s Essay Upon the Life, Writings, and Character of Dr. Jonathan Swift [... &c.] (1755) was reviewed by Burke in the Annual Register in 1756.

Tracts Relative to the Laws against Popery (given in The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing, Derry: Field Day 1991, Vol. 1), known variously as ‘Fragments of a Tract on the Popery Laws’, and prob. written 1761 - acc. Cone; op. cit., supra, p.43 - but dated 1763. See also0 C. C. Cruise O’Brien, in The Great Melody, 1992): ‘The Tracts were neither completed nor any part published in Burke’s lifetime though fragments occupying some 70pp. appear in the Collected Works (1899 edn., VI, p.311), dated 1764.’ (p.40.)

Oliver Goldsmith wrote of Burke in Retaliation: ‘born for the universe, narrowed his mind / And to party gave up what was meant for mankind.’ Further, ‘Though fraught with all learning, yet straining his throat / To persuade Tommy Townsend to lend him his vote’ - lines favoured by James Joyce, as recorded by Padraic Colum in his contribution to Ulick O’Connor, ed., The Joyce that We Knew (Cork: Mercier 1967), p.82. Further, ‘Too deep for his hearers, still went on refining, / And thought of convincing, while they thought of dining ... Though equal to all things, for profit unfit, / Too nice for a statesman, too proud for a wit.’)

Samuel Johnson’s encomium of Burke as recorded in Boswell’s Life and oft-repeated in various forms (e.g., by Mrs Thrale): ‘Yes, sir, if a man were to go by chance at the same time with Burke under a shed to shun a shower, he would say - “This is an extraordinary man”. If Burke should go to a stable to see his horse drest, the ostler would say - “We have had an extraordinary man here.” On one occasion Johnson told Boswell and Goldsmith, “I love Burke’s knowledge, his genius, his diffusion and affluence of conversation, but I would not talk to him of the Rockingham party.” On feeling ill, he admitted, “That fellow calls forth all my powers. Were I to see Burke now, it would kill me.” (See Samuels, Early Life, 1923; sundry pages.) Further, Johnson said to Arthur Murphy, editor of his Works: ‘I suppose, Murphy, you are proud of your countryman, cum talis sit, utinam noster esset [if that is what he is like, I wish he was one of us].’ (See Copeland, Statesmen, Scholars and Merchants, p.302n.; Ayling, Edmund Burke, 1988, p.28.) Note also, In illness Johnson said, ‘That fellow calls forth all my powers. Were I to see Burke now, it would kill me.’ (Copeland, in ‘Johnson and Burke’, in Edmund Burke 1950, p.303; cited in Conor Cruise O’Brien, The Great Melody, 1992, p.47.)

Tom Paine: contrasting himself as self-made author to Burke, with his ‘catalogue of aristocrats’, Paine asserted: ‘I have not only contributed to raise a new empire in the world, founded on a new system of government, but I have arrived at an eminence in political literature.’ (The Rights of Man, ed., Henry Collins, Pelican 1982, p.198; quoted in Daphne Abernethy, ‘Edmund Burke and the Paradoxes of History’, UUC MA Diss., 1998, p.63.)

Fanny Burney was present at the Warren Hastings Impeachment for Burke’s opening speech as her diary for 13 Feb. 1788 shows by an account of Burke’s entrance having been taken to hear the trial by Arthur Young [OCEL]. As a witness she was divided between what Conor Cruise O’Brien calls ‘affectionate awe’ for Burke and sympathy for Hastings - she being lady-in-waiting to the queen who was highly partial to Hasting. (See Conor Cruise O’Brien, The Great Melody, 1992, p.362; bibl. ‘Diary and Letters of Madame d’Arblay, 1842-1846’, 7 vols.; Vol. IV, p.56.)

Richard Price: Price is the subject of an example in Joep Leerssen’s Remembrance and Imagination: Patterns in the Historical and Literary Representation of Ireland in the Nineteenth Century (Cork UP/Field Day 1996) - where he distinguishes Patriotism from nationalism before the nineteenth-century fusion of these two ideas: "A telling example is the sermon given in 1788 by Richard Price, entitled A discourse on the love of our country, which famously incurred the criticism of Edmund Burke, Price is quick to point out that “love of our country” should not be equalled to “any conviction of the superior value of it to other countries, or any particular preference of its laws and constitution of government.” The same Richard Price, who worked with a club called the London Revolutionary Society (the revolution being that of 1688, whose centenary Price’s Discourse commemorated), worded an address of congratulation to the French National Assembly which began with “disclaiming national partialities, and rejoicing in every triumph of libery over arbitrary power.”’ (Leerssen, op. cit., p.27, citing Alfred Goodwin, Friends of Liberty: The English Democratic Movement in the Age of the French Revolution, Hutchinson 1979, pp.106-12; here p.111.)

[ top ]

Samuel Parr, Correspondence, Vol. II: ‘’Dear Sir, what will you say, or rather, what shall I say myself, of myself? It is now ten o’clock at night, and I am smoking a quiet pipe, after a most vehement, and, I think, a most splendid effort of composition—an effort it was indeed, a mighty and a glorious effort; for the object of it is, to lift up Burke to the pinnacle where he ought to have been placed before, and to drag down Lord Chatham from that eminence to which the cowardice of his hearers, and the credulity of the public, had most weakly and most undeservedly exalted the impostor and father of impostors. Read it, dear Harry; read it, I say, aloud; read it again and again; and when your tongue has turned its edge from me to the father of Mr. Pitt, when your ears tingle and ring with my sonorous periods, when your heart glows and beats with the fond and triumphant remembrance of Edmund Burke - then, dear Homer, you will forgive me, you will love me, you will congratulate me, and readily will you take upon yourself the trouble of printing what in writing has cost me much greater though not longer trouble. Old boy, I tell you that no part of the Preface is better conceived, or better written; none will be read more eagerly, or felt by those whom you wish to feel it, more severely. Old boy, old boy, it is a stinger; and now to other business, [... &c.]’ . (p.196; quoted on Book of the Days; online; accessed 15.11.2009.) Note that Parr remained a Whig after the French Revolution and corresponded with everyone of the same creed, siding implacably with Charles James Fox against William Pitt the Younger. He wrote wrote the epitaphs which are inscribed on the tombs of Burke, Charles Burney, Dr. Johnson, Fox and Gibbon. (There is a Wikipedia article, online.)

William Wordsworth wrote: ‘Genius of Burke! forgive the pen seduced/By spurious wonder and too slow to tell ...’ [cited in Conor Cruise O’Brien, The Great Melody, 1992, p.lxvi]. There is a portrait of Mrs Edmund Burke by Reynolds [see Ayling, 1988].

Mary Shelley [Mary Wollestonecraft] criticised Philosophical Enquiry (1756) in her Vindication of the Rights of Man, quoting the original: ‘This laxity of morals in the female is certainly more captivating to a libertine imagination than the cold arguments of reason, that give no sex to virtue. But should experience prove that there is a beauty in virtue, a charm in order, which necessarily implies exertion, a depraved sensual taste may give way to a more manly one - and melting feelings to ration satisfactions.’ (Vindication of the Rights of Man, 1960 edn., p.116; cited in Terry Eagleton, ‘Aesthetics and Politics in Edmund Burke’, Michael Kenneally, ed., Irish Literature and Culture, Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1992, pp.25-34, p.30.)

Thomas Davis, ‘The Young Irishman of the Middle Classes’, a lecture given to the TCD Historical Society in 1839 and reprinted in three instalments in The Nation, 1848 with footnote remarking: ‘Edmond [sic] Burke’s “presiding principle and prolific energy”seems the finest, indeed a perfect rule of action for self-government. See the Reflection on the French Revolution, p.220 to 225 of the Dublin edition.’ (Given in The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing, gen. ed., Seamus Deane (Derry: Field Day 1991, Vol. 1, p.1281.)

W. B. Yeats (1), in verse: ‘And haughtier-headed Burke that proved the State a tree,/That this unconquerable labyrinth of the birds, century after century,/cast but dead leaves to mathematical equality [Collected Poems, 1955, 268].

W. B. Yeats (2) - in prose: ‘Burke [proved] that the State was a tree, no mechanism to be pulled in pieces and put up again, but an oak tree that had grown through centuries (Senate Speeches, p.172).

W. B. Yeats (3) - his view of Burke, with Grattan, Berkeley, and Goldsmith, as Whigs although they did not know it: ‘Burke was a Whig / ... Whether they knew or not, / Goldsmith and Burke, Swift and the Bishop of Cloyne / All hated Whiggery; but what is Whiggery? / A levelling, rancorous, rational sort of mind / That never looked out of the eye of a saint / Or out of drunkard’s eye.’

W. B. Yeats (4) - “The Seven Sages”, 1932: ‘American colonies, Ireland, France and India / Harried, and Burke’s great melody against it.’ - lines used as title by Conor Cruise O’Brien (1992).

[ top ]

Leslie Stephen called Burke’s speeches on the Tea Act (19 April 1774) ‘the only English speeches which may still be read with more than an historical interest when the hearer and the speaker have long turned to dust.’ (English Thought in the Eighteenth Century, Vol. II, 219; cited Stayling, op. cit.)

Lord Macauley’s remarks on Burke occur in his account of Hastings, printed in Edinburgh Review, Oct. 1841.

James Joyce refers to Edmund Burke only in his listing of the Anglo-Irish writers in “Ireland, Isle of Saints and Sages” (1907): ‘[…] Edmund Burke, whom the English themselves called the modern Demosthenes and considered the most profound orator who had ever spoken in the House of Commons.’ (Ellsworth Mason, ed., Critical Writings, 1959, p.170.)

Brian Friel employs Burke’s celebrated eulogy of Marie Antoinette from Reflections in Philadelphia, Here I Come (see Friel, q.v.)

Terry Eagleton [citing Mary Shelley, as above] concludes that Burke divorces beauty (woman) from moral truth (man), and that his verson of the matter is that ‘an enervated beauty must be regularly shattered by a sublime whose terrors must in turn be quickly defused, in a rhythm of erection and detumescence.’ (Terry Eagleton, ‘Aesthetics and Politics in Edmund Burke’, Michael Kenneally, ed., Irish Literature and Culture, Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1992, pp.25-34, p.31.)

Seamus Deane, “Christmas at Beaconsfield”, a long poem on Burke, is excerpted in Andrew Carpenter & Peter Fallon, eds., The Writers: A Sense of Place (1980), pp.29-32. It concerns the visit of Sir James Mackintosh to Beaconsfield at Christmas 1796. Prefatory note: ‘[...] Mackintosh, famous then as the author of a tract supporting the French Revolution, is about to be converted by Burke to an hostility towards the Revolution and all it represents. His career is about to be blighted. It is snowing outside.’

‘The old violence’: Burke’s phrase is echoed in John Fitzgibbon [Lord Clare]’s speech in the House of Lords, identifing ‘the Act of violence’ as the basis of the Anglo-Irish nation and hence warning that an accommodation with Catholics spells a risk of reparation. [See reference under Quotations 2 - as infra; also under John Fitzgibbon, Lord Clare - as infra.]

Tax error: Dictionary of National Biography (Shorter edn.) reports in error that Burke ‘advocated taxing Irish absentees’ rather than voting against this measure [check].

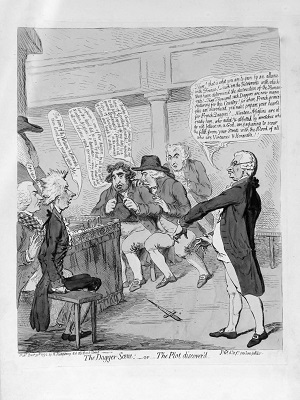

Is this a …?: Burke shocked the Members of the House of commons at Westminster by flinging a dagger on the floor in mid-oration, 28 Dec. 1792, objecting to the restriction of aliens in the prologue to the war with France (cited by Austen Clarke in A Penny in the Clouds 1968, Chap 3.)

How sublime? Dr John Baillie (obiit 1743) posthumously published An Essay on the Sublime (London: Printed for R. Dodsley and sold by M. Cooper 1747), [iii], 41, [3]pp.(8vo); rep. with preface by Samuel Holt Monk [Augustan Rep. Soc., No.43] (Los Angeles 1953), vi, 41pp.

[ top ]

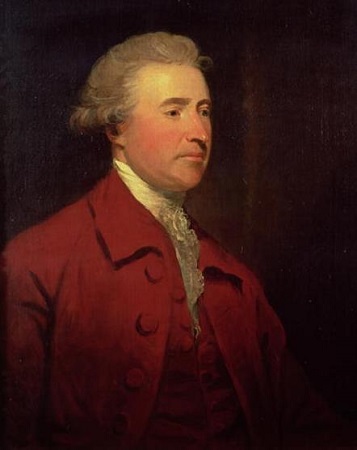

Portraits: Oil portrait by Joshua Reynolds, bequeathed to NGI by Miss Emily Drummond, 1930; James Barry, port. of Burke, TCD [quill in hand]; ‘Ulysses and a companion escaping from the Cave of Polyphemous’ (Crawford Gallery, Cork), with Burke as Ulysses [infra]; unfinished port. of Burke with Lord Rockingham; mezzotint by John Jones, after Zoffany (who also portrayed Warren Hastings and his wife in the manner of Gainsborough); statue of Burke at College Green, Dublin [TCD Front Gate] by J. H. Foley (1868); Burke reading his India Bill to Charles Fox, who later carried it through Parliament, by Thomas Hickey (1741-1824) [National Portrait Collection]; Edmund Burke, by Thomas Worridge, purchased by Dermod O’Brien PRHA from Burke fam. and used as frontis. in Copeland ed., Letters (1958) [for the foregoing see Anne Crookshank, Irish Portraits Exhibition (Ulster Mus. 1965)]. See also ills. in Conor Cruise O’Brien, The Great Melody (1992): Lord Rockingham and Edmund Burke, unfinished portrait by Reynolds (Fitzwilliam, Cambridge); Ills. incl. Mrs Sheridan (Mansell Collection); Richard Burke (Earl Spencer/Nat. Portrait Gallery); Burke as Jesuit (cartoon, BML); Charles Fox and Edmund Burke, ‘The Wrangling Friends’, Cruikshank, BML); James Gillray, ‘The battle of Bow-Street’, July 1788, shows Charles james Fox and R. B. Sheridan complaining to the Chief Magistrate, Sir Sampson Wright about over-zealous use of military, while Burke in spectacles raises his hands (see Edmund Burke: Life in Caricature). Note that Burke was represented as crypto-Catholic wearing a biretta by Gillray and others.

Ulysses Burke: James Barry’s painting “Ulysses and a companion escaping from the Cave of Polyphemous” (Crawford Gall., Cork), places has Burke’s head on Ulysses and Barry’s on his companion’s [see James Barry, q.v.].

RIA Conference (Royal Irish Academy, Dublin; 2007): “Edmund Burke and Irish Literary Criticism, 1757 to 2007” (Wed. 25 April 2007): ‘April 2007 marks the 250th anniversary of the first publication of Edmund Burke’s classic in aesthetics and the philosophy of literary criticism, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful. This academic conference would seek to acknowledge and celebrate the occasion, but it will also propose a renewal and a re-examination of the 18th century and late Enlightenment roots of Irish literary criticism. Burke’s Philosophical Enquiry, for instance, constructs a rationalist hierarchy of the passions that strives to harmonise the concerns of Greco-Roman aesthetics and Enlightenment (Lockean and Hobbesian) psychology in Part I. Furthermore, Parts II to IV construct an aesthetics of a Gothic sublime and of a gendered beautiful in advance of the development of the Gothic novel and the Anglophone novel of sense and sensibility in the last third of the 18th century. Part V offers an analysis of image and word relations which contemporary theorists (W. J. T. Mitchell and others) have only recently recognised as precociously modern and insightful. Perhaps most perceptively Burke constructs in his “Introduction on Taste” for the book’s second edition a triadic model of faculty psychology which influences the shape and substance of Immanuel Kant’s critical philosophy (pure reason, practical reason, judgement) but also Sigmund Freud’s tripartite construction of human psychological motivation (id, ego, superego). [Cont.]

RIA Conference (2007) - cont.: Oddly enough, Edmund Burke’s Philosophical Enquiry seems not to receive due attention as a classic, perhaps even foundational text, of Irish literary criticism. For instance, Burke features as the first writer anthologised in Stephen Regan’s Irish Writing: An Anthology of Irish Literature, 1789-1939 (Oxford UP, 2004) but it’s Burke’s controversial effusion over the figure of Marie Antoinette and his defence of the right of monarchs [ Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790)] that students of Anglophone Irish writing get to read. A second, clear aim of this proposed conference would be to open a discussion of the connections and continuities of modern and contemporary Irish literary criticism to the constructions, issues, problems and possibilities of Edmund Burke’s 1757 Anglophone Irish classic, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful. / This academic conference will be a one-day event, held in the meeting rooms of the Royal Irish Academy , 19 Dawson Street , Dublin 2, on Wednesday, 25 April 2007. Dr Claire Connolly, Senior Lecturer in English Literary and Cultural Criticism at the University of Wales at Cardiff, will offer an opening keynote speech in the morning and a closing plenary response at the end of the afternoon will be provided by Luke Gibbons, Keogh Family Professor of Irish Literature and Cultural Criticism at the University of Notre Dame, Indiana and Director of the Keogh Institute in Dublin.

RIA Conference (2007) - cont.:A general ‘Call for Papers’ (deadline, Friday, 2 February 2007) seeks titles and abstracts of 20-minute papers for four set panels. Abstracts should run no longer than 300 words and may be e-mailed or posted to the principal organiser of the conference, Professor Brian Caraher (see information below). The organisers of this one-day event are seeking papers for the following four nominated panels: 1] Edmund Burke: aesthetics and politics; 2] Edmund Burke and cultural modernity; 3] Edmund Burke and Irish literary and cultural theory; 4] Edmund Burke and the tropes and thematics of Irish literary criticism. / The conference is jointly sponsored by the Royal Irish Academy, with a group of co-organisers drawn from its Committee for Irish Literatures in English (namely, Terence Brown, Brian Caraher and Riana O’Dwyer), and Queen’s University Belfast, with a group of co-organisers drawn from the School of English (Brian Caraher, David Dwan, Siobh án Kilfeather). Scholars and students of Edmund Burke, modern Irish writing in English, Irish literary criticism, philosophy of literary criticism and aesthetics are the target audience. Attendance will be drawn from Irish universities, north and south, as well as panellists and delegates from throughout the UK and North America. Contact information for abstracts & further information: Professor Brian Caraher at b.caraher@qub.ac.uk [email], or [by land] Brian G. Caraher, Chair of English Literature, Research Director, Modern Literary Studies, School of English, Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast BT7 1NN (Northern Ireland). Posted by Royal Irish Academy , 19 Dawson Street, Dublin 2. Tel: +353-1-6762570, Fax: +353-1-6762346 Copyright RIA 2005; www.ria.ie [email].

[ top ]