Life

| [Thomas Henry Burke]; b. 29 May 1829, at Waterslade House, Tuam; son of William Burke; descended from Sir Ulick Burke of Glinsk, recipient of a baronetcy from Charles I in 1628; br. of Theobald Burke, 13th Baronet Glinsk; also br. of Augustus Nicholas Burke, an artist; brought up in Knocknagur [Tuam] Co. Galway; ed. Oscott College, Sutton Coldfield, nr. Birmingham; later in Belgium and Germany;appt. clerk in Dublin Castle, 1847; m. a dg. of Thomas N. Redington [q.v.], Irish Under-Sec. of State (Ireland); |  |

| worked as priv. sec. to three Chief Secretaries, Cardwell, Peel, and Fortescue-Parkinson; appt. Permanent Under-Secretary for Ireland, 1863-82 [var.1869], associated with the Coercion policy during Land War, 1879-82; personally intervened to prevent the evictions on the Kirwan Estate at Carraroe, Co. Galway - writing in a report to Wm. Edward Forster (Chief Sec. for Ireland) of the ‘sad flood of light this throws on the Irish land question ... an absentee landlord, careless sub-agents, fraudulent bailiffs and a wretched tenantry’; | |

| Burke was the main promoter of the Intermediate Education Act (1878) and grant-award system from which James Joyce q.v.] was a beneficiary; a Home-ruler and also a law-and-order man, he alienated nationalists with his support of the Crime [Coercion] Acts designed to protect property in the Land War and thus became a target for the National Invincibles - a splinter group of the Irish Republican Brotherhood [IRB] - which planned his assassination when he was walking with Lord Frederick Cavendish (apparently a accidental victim) near the Vice-Regal Lodge in the Phoenix Park, 6 May 1882; | |

| bur. with his father under a Celtic Cross in Prospect Cemetery, Glasnevin, 9 May 1882; the ensuing hunt and prosecution of the assassins was conducted by Det. Superintendant John Mallon of G Division; JHB left an estate of £1,901 11s. 4d; a monument to Burke was erected in Glasnevin y the Irish Resident Magistrates; there is an annual GCSE Award dedicated to Burke under the remit of the Northern Ireland Education Dept. ODNB DIH |

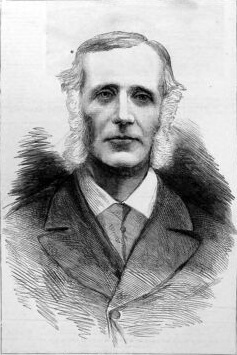

Note: The portrait of Thomas Henry Burke on the right of this page [above] was published in Le Monde Illustré (aka The Graphic, 20 May 1882) where it was accompanied by another of his funeral. It also appeared inin Frank Hugh O’Donnell, The History of the Irish Parliamentary Party (1910), Vol. II, facing p.[121] - where O’Donnell writes: ‘I knew of Mr. Burke as an exceptionally able and conscientious official. In the subsequent articles of the Times on Parnellism and crime, most of the facts were quite correct, but the straining after foregone conclusions made a blurred picture after all.’ (p.120.) |

[ top ]

Criticism

Tom Corfe, The Phoenix Park Murders: Conflict Compromise & Tragedy In Ireland 1879–1882 (London: Hodder & Stoughton 1968); Senan Molony, Assassins in the Park: Murder, Betrayal and Retribution (Cork: Mercier Press 2006), 192[285]pp.

[ See the account given of the Phoenix Park murders and the ensuing trials by Peter O’Brien (then Q.C. and later Lord Chief Justice of Ireland) in his Reminiscences (1916) - as attached. ]

See also Frank O’Connor & Hugh Hunt, The Invincibles, ed. Ruth Sherry (Newark: Proscenium 1980) - a play.

|

||||||

[ top ]

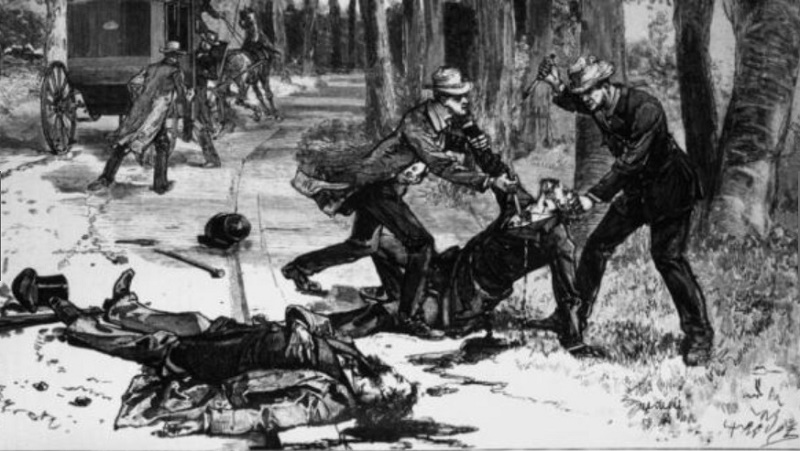

D. A. Chart, The Story of Dublin [Medieval Town Ser.] (London: Dent 1907): ‘[T]he worst incident of these troubled times was the cold-blooded and deliberate assassination of Lord Frederick Cavendish, Chief Secretary, and Thomas Burke, Under Secretary, in the Phoenix Park on the 6th May 1882. Burke, as the actual, though not the nominal, head of the Irish administration for many [124] years, had long been marked out for vengeance, but Cavendish was an Englishman newly arrived in Ireland. The crime was the work of the physical force extremists, who conducted their operations from America.’ (pp.124-25.) Further - writing of the scene of the assassinations: ‘On the road facing the Lodge, in broad daylight and in full view of the viceroy’s window, the dastardly murder of Cavendish and Burke, chief and under secretaries, was perpetrated. Several persons witnessed the crime from a distance, but thought it no more than a mere drunken brawl. The spot is not now marked in any way, though formerly there was a cross let into the ground. Perhaps the whole tragic business is best forgotten and forgiven.’ (p.312.)

Shane Leslie, The Irish Tangle for English Readers (1946), remarks: ‘Burke’s murderer remained impenitent in prison, despite the loving attention of a namless Sister of Charity. At last he was told she was Burke’s sister. Then he broke down. It was all so Irish and dramatic.’ (p.20.)

Friedrich Engels on the Phoenix Park Murders: ‘But the Fenians themselves are being drawn increasingly to a type of Bakuninism, the assassination of Burke and Cavendish could have pursued the sole aim of thwarting the compromise between the Land League and Gladstone [...]. In this light the “heroic deed” in Phoenix Park appears as purely Bakuninist, boastful and senseless “propaganda par le fait”, if not a crass foolishness.’ (‘About the Irish Question’ [1888], K. Marx & F. Engels, On Colonialism, Lawrence & Wishart 1968, p.264; quoted in Emer Nolan, James Joyce and Irish Nationalism, London: Routledge 1995, p.126.)

Maurice Headlam recounts that Lord Spencer, Viceroy, saw what he took to be a drunken brawl through his window, and that no monument was raised at the site or the murders ‘since the Liberal government thought it would provoke enmity, and the Nationalist party were not proud of the deed.’ (Irish Reminiscences, 1947; p.39.)

Family records: Thomas Burke was son of William Burke of Knocknagur, Co. Galway, and his wife Mary Anne, sister of Nicholas, Cardinal Wiseman; Burke’s family was connected with that of Sir Ulick Burke of Glinsk, Co. Galway, on whom a baronetcy was conferred by Charles II in 1628 [see ODNB]. In April 1851 he was appointed private secretary to Sir Thomas Redington [Sybil’s maternal grandfather], then Under-Secretary for Ireland. In 1869, he was himself appointed Under-Secretary. Burke was assassinate 6th May, 1882, and buried in Glasnevin Cemetery. The viceroy Earl Spenser erected a memorial window in the Dominican Church, Dublin; his sister was given a govt. pension; his estate at his death was £1,901.11.4. (Source: Family record of Sybil le Brocquy [née Staunton] - which includes an unidentified allusion to Fanny Xaviera, only dg. of Thomas Tucker of Brook Lodge, Sussex.)

Myles Dungan, ‘Writing Nearly on the Wall for Parnell’, in The Irish Times (13 Feb. 2010), Weekend Review, p.6. - mentions a reference to Burke’s death at the hands of the Invincibles in a note purportedly written by Parnell but actually forged by Piggott: “On 7 March 1887, in the first of a number of articles, the London Times made the not-altogether astonishing allegation of links between Irish parliamentarians and agrarian crime stretching back to the Land War of 1879-82. The series, entitled Parnellism and Crime, appeared to be dying a natural death for want of substance when the Times, on page 8 of its edition of April 18th, published a facsimile of a highly incriminating letter bearing the signature “Chas. S Parnell”. The text of the brief note, dated nine days after the infamous Phoenix Park murders of the newly arrived Irish chief secretary Lord Frederick Cavendish and under-secretary, Thomas H. Burke, expressed the view that while the killing of Cavendish had been a regrettable accident Burke had got his just deserts for a career of actions inimical to nationalist interests. If genuine, the letter would have been a fatal blow to the political career of the man already lionised as “The Uncrowned King of Ireland”. Parnell, oddly, given the furore that arose, had to be cajoled into making a belated denial that the signature was his. The note itself was clearly not in his handwriting. Privately he dismissed the signature, rather blithely, as a forgery, observing of his alleged middle initial (“S” for Stewart) that “I did not make an ‘S’ like that since 1878”. [...] (For full text, see RICORSO Library, “Criticism > History”, via index - or as attached.)

[ top ]

D. J. Doherty & J. E. Hickey, A Chronology of Irish History Since 1500 (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1989), cite under ‘Parnellism and Crime’ the supposed letter by Charles Stewart Parnell of 7 March 1887 [recte 18 April], actually forged by Pigott, in which the author writes, ‘But you can tell all others concerned that though I regret the accident of Lord F. Cavendish’s death, I cannot refuse to admit that Burke got no more than his deserts.’

|

|||||

|

[ top ]

Notes

R. R. Madden: Dr. Madden was joined by T. H. Burke in persuading Disraeli to provide a civil list pension for Mrs. Michael Banim, relict of the novelist (See Irish Literature, gen. ed. Justin McCarthy, 1904; under ‘Michael Banim’.)

C. S. Parnell: The most offensive content in the letter of 18 April 1887 forged by Richard Pigott included the assertion that Thomas H. Burke deserved his fate at the hands of the Invincibles on account of his anti-nationalist role in Irish affairs. (See further remarks in review of Myles Dungan’s article on the Parnell Commission of 1887 under Parnell, infra.)

Lord Spencer: ‘Please make acquaintance with the Under Secretary T. H. Burke. He was the Irishman of all I know in whom I placed the greatest trust. I certainly knew him better than any other man in the country, but my constant intercourse with him only made me like and trust him more and more.’ (Letter to W. E. H. Gladstone on the eve of the latter’s visit to Ireland in 1887. [Information supplied to Ricorso by James H. Murphy, Oct. 2011.]

The Invincibles (I): The Invincibles’ plot compassed the idea of capturing W. E. Forster, the unpopular Chief Secretary [called “Buckshot” Forster], and taking him to John Street to be killed there. They were arrested for the Phoenix Park assassinations on 13 Jan. 1883, and both charged [in Feb.] and tried in April for murder on 6 May 1882. Before the trial Superintendent Mallon of the Dublin Metropolitan Police (G Division) induced James Carey, the leader, and Michael Kavanagh to testify against the others. Carey was a bricklayer from Chapelizod with a business at Denzille St. and a name in corporation politics. He acted in the conspiracy as spotter, pointing out the intended victim, Burke, from a cab near the scene but did not himself take part in the killings. The first blow was struck at Burke by Joseph Brady and the next at Cavendish by Tim Kelly. Those convicted along with Brady and Kelly were Daniel Curley, Michael Fagan, and Thomas Caffrey - all of whom were hanged in Kilmainham Gaol, Dublin, between 14 May and 4 June 1883. The hangman was William Marwood. [See further under James Joyce, Notes > Joyce’s People - infra.]

There is a memorial plaque to the Invincibles giving their names and dates of execution between 14 May and 4 June 1883: Anseo a crochadh Joseph Brady (14.5), Daniel Curley (18.5), Michael Fagan (28.5), Thomas Caffrey (2.6), Timothy Kelly (9.6.) James Fitzharris (“Skin the Goat”; 1833-1910), who drove the cab, served 15 years in prison and did not inculpate any of his colleagues. There is also a plaque at his grave citing the names of the hanged men. Those considered leaders of the Invincible organisation who were not charged and later made public appearances in America included John Walsh, Patrick Egan, John Sheridan, Frank Byrne, and Patrick Tynan.

The Invincibles (II): Burke was said to have been ‘executed by Order of the Irish Invincibles’ according to a card delivered by the principles to the Irish newspapers. James Carey, who turned Crown witness, was killed by Patrick O’Donnell on board the Melrose out of S. Africa on route to Natal, having out the Kinfauns Castle with his wife Mary [née McKenna] under the name Power - leaving London on July 6. The Powers formed a convivial friendship on the voyage with O’Donnell, also a bricklayer, who was notified by an English traveller called Cubitt that Power was actually Carey as he had learned in the newspapers - a copy of which he showed to O’Donnell. O’Donnell drew a gun on Carey and shot him several times on 29 July. It remained unclear whether he was moved by spontaneous anger or prior intent. O’Donnell was hanged in London on 17 December for the offence. (See Michael Newton, The Age of Assassins, Faber 2011; also J. L. McCracken, The Fate of an Infamous Informer, in History Ireland (2001).

Wikipedia: After numerous attempts on his life, Chief Secretary for Ireland William Edward “Buckshot” Forster resigned in protest of the Kilmainham Treaty.[3] The Invincibles settled on a plan to kill the Permanent Under Secretary Thomas Henry Burke at the Irish Office. The newly installed Chief Secretary for Ireland, Lord Frederick Cavendish, was walking with Burke on the day of his arrival in Ireland when the assassins struck, in Phoenix Park, Dublin, at 17:30 Saturday, 6 May 1882. The first assassination in the park was committed by Joe Brady, who attacked Burke with a 12-inch knife, followed in short order by Tim Kelly, who knifed Cavendish. Both men used surgical knives. The British press expressed outrage and demanded that the “Phoenix Park Murderers” be brought to justice. A large number of suspects were arrested. By playing off one suspect against another, Superintendent Mallon of “G” Division of the Dublin Metropolitan Police got several of them to reveal what they knew.[4] The Invincibles’ leader, James Carey, and Michael Kavanagh agreed to testify against the others. Joe Brady, Michael Fagan, Thomas Caffrey, Dan Curley and Tim Kelly were hanged by William Marwood in Kilmainham Gaol in Dublin between 14 May and 4 June 1883. Others were sentenced to long prison terms. No member of the founding executive, however, was ever brought to trial by the British government. John Walsh, Patrick Egan, John Sheridan, Frank Byrne, and Patrick Tynan were welcomed in the United States, where sentiment toward the murders was less severe, although not celebratory.”

Further: In Episode Seven of James Joyce’s Ulysses Stephen Dedalus and other characters discuss the assassinations in the offices of the Freeman newspaper. In Episode Sixteen[,] Bloom and Dedalus stop in a cabman’s shelter run by a man they believe to be James “Skin-the-Goat” Fitzharris. The Invincibles and Carey are mentioned in the folk song “Monto (Take Her Up To Monto)”. (See Wikipedia entry on The Irish National Invincibles - online; accessed 21.09.2020.)

“Take her Up To Monto ...” [...]

When Carey told on Skin-the-goat,

O’Donnell caught him on the boat

He wished he’d never been afloat, the filthy skite.

‘twasn’t very sensible

To tell on the Invincibles

They stood up for their principles, day and night by going up to Monto Monto ...

T. D. Sullivan, Recollections of Troubled Times in Irish Politics (Dublin 1905): ‘The “Phoenix Park Tragedy” did not close with the terrible deeds of the ist of May. A vigorous quest for the perpetrators was immediately started by the Government, but not until eight months after the event was any clue to their identity discovered. On the I3th of January, 1883, James Carey, James Mullet, Joseph Brady, Timothy Kelly, Daniel Curley, and others were arrested in Dublin as principals in the crime ; further captures were made within a few days. While in prison Carey was induced to turn “Queen’s evidence” against his fellow-captives, who had been his brethren in a secret society. — small in numbers but more “advanced” than the Fenians — which he and they had formed for desperate purposes, and to which they proudly gave the name of “The Invincibles.” Of the existence of this body the public, up to that time, had no knowledge, its members having kept their own counsels and refrained from advertising themselves in any way. Carey was led to take this course by stories told him by his jailors, to the effect that several of his companions in misfortune had offered to make full revelations regarding the conspiracy and the crime; and by intimations and suggestions that his services in that way would be acceptable, if he choose to render them — in which event his life would be spared, and his future provided for. At this point Carey’s fortitude broke down; he penned a voluminous confession, and at the trials of his comrades, which took place on various dates in April 1883, he gave evidence which left them no chance of escape. Convictions followed in all cases; several of trie conspirators were sentenced to penal servitude, five were condemned to death, and four — Joseph Brady, Daniel Curley, Timothy Kelly, and Michael Fagan were executed.” (p.204.)

Sullivan goes on to describe the fate of Carey who was shot my a certain Patrick O’Donnell who recognised his on the Kinfauns Castle from London to Cape Town, on which ship Carey disguised himself as James Power but was exposed by a newspaper portrait which came into O’Donnell’s hands at Cape Town. O’Donnell was later tried and executed in London. (Ibid., pp.205-06.)

‘The immediate effect of the Phcenix Park outrage was to darken the political skies, and blot the vision of peace and friendship that a moment before had looked so fair. Social and party strife went on no less fiercely than before. The landlords and the loyalist party were in fighting temper ; evictions were carried out in increased numbers, and under circumstances of great cruelty ; a spirit of vengeance was evoked amongst the unfortunate victims of oppression and wrong, which led to the commission of deplorable crimes ; these were followed in turn by the pains and penalties of the law, and so the vicious circle was completed.’ (p.206; end of Chap. XXII; available online; accessed 22.05.2024.)

Carey’s Motives - T. M. Sullivan writes in a note to his account of the Phoenix Park Murders: ‘In his evidence at the Invincible trials Carey said: — “I am no informer; I got no one arrested.” In reply to questions on cross-examination (February i8th, 1883), ne made the following memorable statement : — “I became a member of the Assassination Committee when the country was in a bad state, when coercion was in full force, when the popular leaders were in prison, when any man might be thrown into prison at a moment’s notice, and kept there without trial. But for that the Committee would not have had so many recruits.”’ (Quoted in T. M. Sullivan, Recollections of Troubled Times in Irish Politics, Sealy, Bryers & Walker 1905, p.380.)

The Parnellite response: ‘We appeal to you to show by every manner of expression that almost universal feeling of horror which this assassination has [201] excited. No people feels so intense a detestation of its atrocity, or so deep a sympathy for those whose hearts must be seared by it, as the nation upon whose prospects and reviving hopes it may entail consequences more ruinous than have fallen to the lot of unhappy Ireland during the present generation. We feel that no act has ever been perpetrated in our country during the exciting struggles for social and political rights, of the past 50 years, that has so stained the name of hospitable Ireland as this cowardly and unprovoked assassination of a friendly stranger, and that until the murderers of Lord Frederick Cavendish and Mr. Burke are brought to justice, that stain will sully our country’s name.’ (Signed) CHARLES S. PARNELL.

JOHN DILLON.

MICHAEL DAVITT.(Quoted in T. M. Sullivan, Recollections of Troubled Times in Irish Politics, Sealy, Bryers & Walker 1905, pp.200-01.) Note - Sullivan adds: ‘This address was published all over the three kingdoms on Monday, May 8th. Most people felt that it befitted the leaders of the Nationalist party to denounce the crime ; but members of the “extreme section” thought the protestation was needlessly violent. They were angry with Messrs. Parnell, Dillon, and Davitt for the issue of this proclamation, but with the first-named particularly, as he was the leader of the party. There is reason to believe that Mr. Parnell never liked the terms of the document, which he thought were too emotional ; but, in this, as in various other matters, this man of strangely intermixed qualities had to give way to the pressure put upon him by some of his political associates.’ (Ibid., p.201.)

The forged letter: Dear Sir,

I am not surprised at your friend’s anger, but he and you should know that to denounce the murders was the only course open to us. To do that promptly was plainly our best policy. But you can tell him and all others concerned that, though I regret the accident of Lord F. Cavendish’s death, I cannot refuse to admit that Burke got no more than his deserts. You are at liberty [222] to show him this, and others whom you can trust also, but let not my address be known. He can write to the House of Commons. Yours very truly,

Charles S. Parnell.

Quoted in Howard Parnell, Charles Stewart Parnell: A Memoir by His Brother (NY: Holt 1914), pp.221-22 [my italics].

[ top ]

Dan Curley: There is a song commemorating the fate of Daniel Curley - a member of the Invincibles though not actually one of the killers - who refused to turn Queen’s Evidence against his associates and was hanged with the others, convicted on the evidence of James Carey (the informer). One stanza, devoted to Carey, reads: ‘May he be evicted, may his wife be a widow, / May his children turn wanderers from Ireland’s green shore, / May the curse of the widow and orphan stay on him / My husband Dan Curley I’ll see him no more.’ An annual commemoration is conducted at the pebble cross at the site of the assassination. (See ‘Frank McNally on a forgotten song about the Phoenix Park Murders’, in “Irishman’s Diary”, The Irish Times, 7 May 2019.)

| Further: |

|

| —McNally, “Irishman’s Diary”, in The Irish Times (7 May 2019) - online; accessed 21.09.2020. |

| See also Deaglán de Bréadún, review of The Phoenix Park Murders: Conspiracy, Betrayal and Retribution by Senan Molony, in The Irish Times (19 Aug. 2006). |

|

| —Deaglán de Bréadún, reviewing n The Irish Times (19 Aug. 2006) - online; accessed 21.09.2020. |

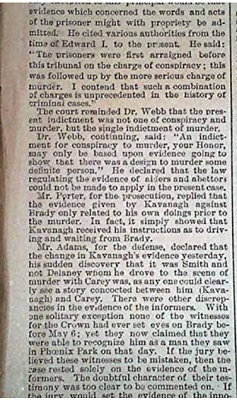

Reports on the Phoenix Park Murder Trial

|

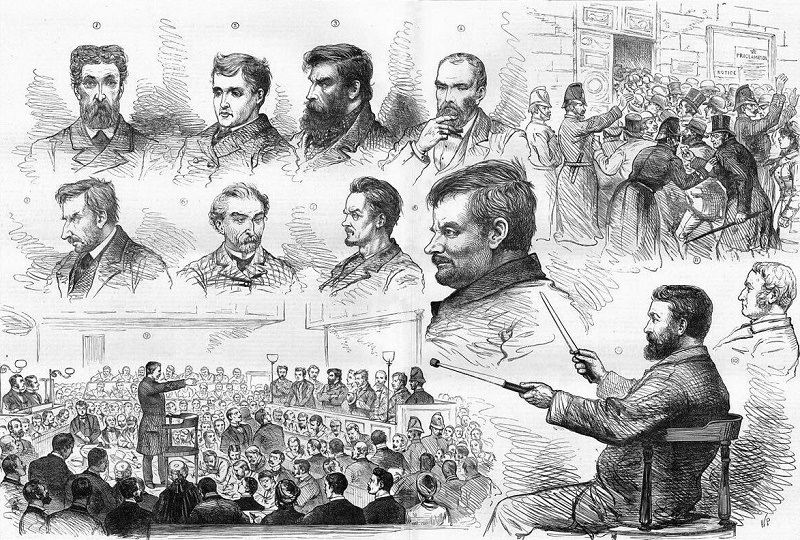

| Le Monde Illustré (1882) |

|

| Examination of the Defendants - engraving offered on e-Bay - online [21.09.2020] |

|

|

|

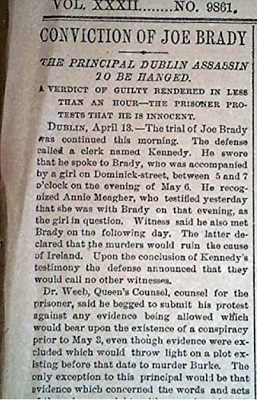

| New York Times report on the conviction of Joe Brady - Amazon online [29.06.2023] | ||

Belfast Public Library holds a copy of Phoenix Park Murders (1882) assoc. in the catalogue with the name of Joe Brady

Michael Fagan: ‘[... A] member of the group known as the “Invincibles” and one of the men responsible for the double assassination of Lord Frederick Cavendish and T. H. Burke on 6 May, 1882. He was executed in Kilmainham Gaol on this day, 28 May, 1883. Michael Fagan was originally from Westmeath but was was employed as a blacksmith by J. Fagan and Sons at 18 Great Brunswick (now Pearse) Street. [... A]t that time a three-year-old Patrick Pearse was living just a few doors down the street from Michael Fagan’s workplace. Pearse’s father James ran a stone carving business with his business partner Edmund Sharpe at 27 Great Brunswick Street. Although Pearse wrote extensively about the Irish revolutionary tradition, he does not seem to have made any reference to the story of the Invincibles.’ (See Kilmainham Gaol - post of 28 May 2025 [online]; ill. with ports of Fagan as an infant and a man, and a photo of the Pearse premises. )

Note: The childhood photo shows Fagan seated in an armchair wearing a skirt and holding a racquet; the the manhood photo is signed by him. A correspondent on the page refers to a photo of Timothy Kelly’s plaque from the corner of Redmond"s Hill (Aungier St) on his phone.

Fate of the Invincibles (Wikipedia extract): The Invincibles’ leader, James Carey, and Michael Kavanagh agreed to testify against the others. Joe Brady, Michael Fagan, Thomas Caffrey, Dan Curley and Tim Kelly were hanged by William Marwood in Kilmainham Gaol in Dublin between 14 May and 4 June 1883. Others were sentenced to long prison terms. No member of the founding executive, however, was ever brought to trial by the British government. John Walsh, Patrick Egan, John Sheridan, Frank Byrne, and Patrick Tynan fled to the United States. Carey was shot dead on board Melrose off Cape Town, South Africa, on 29 July 1883, by County Donegal man Patrick O’Donnell, for giving evidence against his former comrades. O’Donnell was apprehended and escorted back to London, where he was convicted of murder at the Old Bailey and hanged on 17 December 1883. (Available online; accessed 29.05.2025.)

[ top ]