| Life |

| b. 31 March 1872, Upr. Dominic St., Dublin, ed. Christian Brothers School, Strand St.; elected chairman of a debating society (which later merged in Leinster Literary Society under the presidency of Rooney), 1889; meets William Rooney who, though younger, he greatly admired; worked on Irish Independent and The Nation as apprentice printer; at first a follower of Parnell; fnd-member Celtic Literary Society Celtic Lit. Society with William Rooney, 1889; joined Gaelic League and IRB (to 1910); joined John MacBride in S. Africa from Jan. 1897, as a ‘surface worker’ on the Rand (De Beers); |

| worked on the Courant, a British-colony paper; adopted pseud. “Cuguan”, meaning “Dove or Gentle One” in Kaffir; organised 1798 Centenary Celebration in Johannesburg, rallying anti-British Uitlanders; openly supported Boers in South African War, 1899; met both Rhodes and Kruger; returned to Ireland at Rooney’s instigation, 1899; fnd. with Rooney and ed. United Irishman (1899-1906; first iss., 4 March 1899); fnd. Cumann na nGaedheal, a cultural and education association aimed at reversal of anglicisation, 30 Sept., 1900, holding the first Annual Convention on 23 Nov. 1900 in offices of Celtic Literary Society; first proposed Hungarian parallel at Cumann na nGaedhael Convention, 26 Nov. 1902, advocating a dual monarchy on the Austria-Hungarian model of ausgleich (withdrawal) instituted by Déak in 1867, as well as industrial revival through protectionism; |

| objected to Shadow in the Glen as ‘a lie’ because ‘Irish women are the most virtuous in the world’, publishing an alternative version as “In a Real Wicklow Glen” in United Irishman, 1903; at the revival in 1905 he debated with Synge and Yeats in United Irishman, admitting the authenticity of Synge’s folklore record (transcribed from Pat Dirane’s narration), but contending that the original was a ‘callous women’ while Norah Burke was ’a strumpetֻ; supported anti-semitic movement led by Fri. Creagh in Limerick, 1904; issued in the United Irishman during 1904 the articles soon republished as The Resurrection of Hungary, A Parallel for Ireland (Dublin 1904; [3rd edn. 1918]) which sold 30,000 copies; convened a National Council and agreed Sinn Féin policy, Rotunda, 28 Nov. 1905 (chaired by Edward Martyn); fnd-ed. Sinn Féin (1906-14), after a libel action against former paper; |

| experienced a hiatus in political fortunes while Liberals held a majority at Westminster, 1906-11; joined in attack on Synge’s Playboy, 1907; m. 1910; responded to James Connolly’s announcement of class war in Ireland with a denial that ‘Capital and Labour are in their nature antagonistic’ but rather ‘essential and complementary to one another’, 1910; gave lecture at Sinn Fein house (6 Harcourt St.) outlining the policy of abstention from Westminster for elected Irish MPs, as part of a larger lecture series, autumn 1910; reacted to Ulster Covenant by interpreting it as ‘in the spirit of Sinn Féin’ on the grounds that ‘the stronger the Convenant Ulster enters in to resist English law by force the quicker Ulster Unionism as we have known it for a century must burst to pieces’ (Sinn Féin), 1912; |

| joined Irish Volunteers at formation, 1913; contributed series of short lives of Irish men of letters and language movement workers to Dublin Evening Telegraph, 1913, calling for a Dictionary of Irish Biography in Sinn Féin, 1913; ed., with Seamus O’Kelly, Nationality (1915-19); participated in Howth gun-running; not informed of Rising plans and consequently spent the days of the Easter Rising at home in Clontarf; cycled to MacNeill’s house; imprisoned in Reading Jail as an extremist; wrote indignantly to Lynch, the MP taking measures at Westminster on his behalf to dissociate him from the events of 1916; resolved conflict with IRB republicanism in a formula (‘Sinn Fein aims at securing international recognition of Ireland as an independent Irish Republic. Having achieved that status the Irish people may by referendum freely choose their own form of government’); |

| relinquished Sinn Féin presidency to de Valera, Ard Fheis, Oct. 1917; arrested with others for opposing conscription under measures by Viceroy Field-Marshal Lord French, and held at Gloucester Prison, where he edited Gloucester Diamond (a reference to a cobbled street-junction of that name in Dublin); called on separatists to “mobilise the poets”; landslide victory of Sinn Fein with 73 of 105 Irish seats in general election, Dec. 1918; elected Vice-President of Dáil Eireann, Jan. 1919 (in absentio); so-called “German Plot” Sinn Féin prisoners released, March 1919; enjoined Dáil to not to institute a ‘state welcome’ on his return in view of danger to citizens considering British ban on assemblies and processions effected for that reason, thus firmly contesting the wishes of Michael Collins and the Irish Volunteers; Dáil Eireann proscribed, Sept. 1919; |

| appt. Dáil Eireann Minister of Home Affairs, 1920; responded attacks on Catholics by strongly urged a ‘Belfast Boycott’ of Ulster (Protestant) goods, passed in Dáil, Aug. 1920; acting president of Dáil Eireann in absence of de Valera; arrested 26 Nov., 1920, in wake of Bloody Sunday; held in Mountjoy Prison, and visited by Cardinal Clune as emissary of Lloyd George; Gov. of Ireland Act became law in Dec. 1920; released at Truce; involved in secret negotiations on the score that cessation of violence must be accompanied by entitlement of Dáil Eireann to pursue its peaceful business; issued statement to the effect that ‘any peace proposals between the British Government and Ireland should be addressed, not to the Government’s prisoners but to Dáil Eireann’, March 1921; |

| prepared “An Address to the Elected Representatives of Other Nations” for Dáil Eireann; elected MP in Northern Ireland under provisions of the Govt. of Ireland Act; King George V makes placatory address at opening of Northern Parliament, 22 June, 1921; released from prison, 30 June; negotiations at the Mansion House in company of General Smuts, from 4 July 1921, resulting in Truce, 8 July 1921; voted against de Valera’s cabinet decision not to lead the Treaty negotiations in London, and headed Irish delegation of plenipotentiaries negotiating that Treaty, Oct-Dec 1921; wound up the Treaty Debate (‘It has no more finality than we are the final generation on earth’); defeated de Valera for presidency, 1922; strongly opposed to shelling of Four Courts, but agreed under duress; |

| d. 12 Aug., St. Vincent’s Hosp.; P. S. O’Hegarty prepared a bibliography in 1937; described by Churchill as ‘that new phenomenon, a silent Irishman’; his ‘chameleon political nature’ helped him survive the debacle of 1916 to become the leader of the new republican movement (Roy Foster); in writing of John Mitchel and justifying his support of slavery, Griffith spoke of ‘the essential work of dissevering the case for Irish independence from theories of humanitarianism and universalism’ (Pref. to Mitchel’s Jail Journal, 1913 Edn.; see infra); Griffith had a ‘rolling gait’, ascribable to his club foot. ODNB DIB DIH OCIL |

| [ top ] |

|

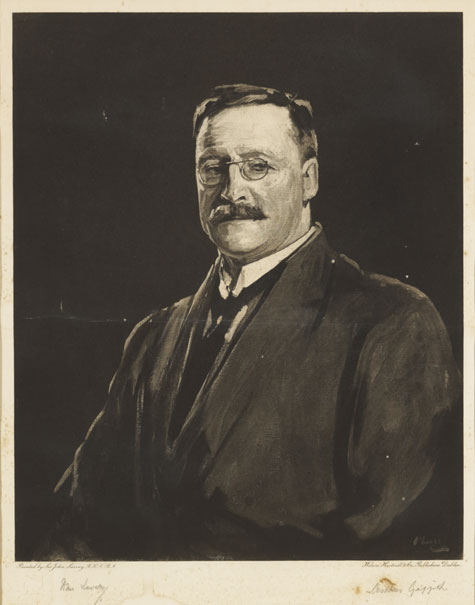

| Engraved frontispiece - from an oil portrait by Sir John Lavery |

Works

|

| Miscellaneous |

|

| Numerous journalistic interventions incl. |

|

| Sundry edns., S. Whelan, ed., Economic Salvation and the Means to Attain It (Dublin: Whelan n.d.); A Study of the Originator of the Sinn Féin Movement (Dublin: Cahill n.d.). |

| See also ... |

|

Bibliographical details

The Resurrection of Hungary: A Parallel for Ireland (Dublin: James Duffy 1904), 99pp.; Do., with new preface by the author, 20 Jan. 1918, with speech given at first Convention of Sinn Fein [3rd edn.] (Dublin: Whelan 1918); another [3rd] edn., The Resurrection of Hungary: A Parallel for Ireland. With appendices on Pitt’s Policy and Sinn Fein (Dublin: Duffy 1918), xxxii, 170pp., ill.; Patrick Murray, intro., The Resurrection of Hungary: A Parallel for Ireland (Dublin: UCD Press 2003), 220pp.

[ top ]

|

| Detail from original oil by Sir John Lavery |

| Biographies |

|

| Sundry studies |

|

|

|

[ top ]

Commentary

Maurice Headlam, Irish Reminiscences (1947), makes a continuous barrage against Griffith and the ‘mentality of Sinn Féin’, drawing upon the fact that Griffith had expostulated against ‘a meek subordinate kind of official in appearance who is in reality the most powerful official in the country - his title is that of Treasurer Remembrancer’, and whose name he gave as ‘a Cockney named Newby’ - this being an error for Headlam’s predecessor by a year at that date, one Hewby (p.127). Headlam adds, ‘if Mr Griffith took [127] so little trouble to verify his references in small things, was he likely to be accurate on more important matters?’ (pp.127-28); in particular he characterises as folly Griffith’s misreading of the Ulster Covenant (p.127).

James Joyce: ‘In my opinion Griffith’s speech at the meeting of the National Council justifies the existence of his paper. He, probably, has to lease out his columns to scribblers like Gogarty and Cohn, and virgin martyrs like his sub-editor. But, so far as my knowledge of Irish affairs goes, he was the first person in Ireland to revive the separatist idea on modern lines nine years ago. He wants the creation of an Irish consular service abroad, and of an Irish bank at home. What I don’t understand is that while apparently he does the talking and the thinking two or three fatheads like Martyn and Sweetman don’t begin either of the schemes.’ (Selected Letters, London: Faber & Faber p.111.)

| Bloom reflects in the “Lestrygonians” chapter of Ulysses (1922): |

|

| —Bodley Head. edn. 1960, p.207; Gabler edn., 1984 [U 8. 462]. |

James Joyce (2): As Frank Budgen tells it, Joyce’s Bloom in Ulysses is the source of the Sinn Féin idea: ‘He informed Arthur Griffith of the Hungarian scheme of action on which Sinn Fein was founded although he must have done so in a scientific, not a combative spirit. All the others in Barney Kiernan’s are proud, violent men, willing to kill and be killed for their cause. Not so Bloom. For him the human body, its well-being and continued existence, is the greatest good, the worthiest cause of all.’ (See Frank Budgen, James Joyce and the Making of Ulysses [.... &c.] 1834; 1972 Edn., p.168.)

Peter Costello, The Heart Grown Brutal: The Irish Revolution in Literature ... 1892-1939 (Gill & Macmillan 1977), p.208, citing Oliver St. John Gogarty’s account of the death of Griffith and his acid reflections on it. (See under Gogarty.)

Joseph Lee, Ireland 1912-1985: Politics and Society (Cambridge UP 1989): ‘Arthur Griffith once said that it would be a much more difficult task to put an end to favouritism and family influence in appointments under local bodies in Ireland than to drive the British army from the country.’ (Connaught Telegraph, 10 Jan 1931; Lee, op. cit., p.163.)

Joseph Sweeney, ‘Why “Sinn Féin?”’, Éire-Ireland, 6, 2 (Summer 1971), pp.33-40, notes that ‘Arthur Griffith first put forward his Sinn Féin ideas in a speech to Cumann na nGaeldheal, a Dublin political group favouring Irish independence in October 1902. He expanded them in a series of articles in his newspaper, The United Irishman, and collected them in book form as The Resurrection of Hungary, in 1904. On the premise that Ireland was a nation, Griffith held that, “the four-and-a -quarter millions of unarmed people in Ireland would be no match in the field for the British Empire. If we did not believe so, as firmly as we believe the eighty Irishmen in the British House of Commons are no match for the six hundred Britishers opposed to them, our proper residence would be a padded cell.” In a High Tory move of absolute constitutionalism, Griffith proposed Ireland restore the constitution on 1782 and not accept any subsequent British legislation, such as the repeal of the Act of Union, follow the Hungarian deputies of 1861, stay at home, reestablish an Irish parliament, and by refusing to recognise the British parliament’s right to legislate for Ireland, set up a dual monarchy. This is why in its early days Sinn Féin was known as “the Hungarian policy”’ (p.33) Sweeney cites R. M. Henry, The Evolution of Sinn Féin (NY: B. W. Huebsch 1920).

[ top ]

Padraic Colum, ‘Life in a World of Writers’ [interview], in Des Hickey & Gus Smith, eds., A Paler Shade of Green (London: Leslie Frewin 1972), pp.13-22: ‘I admired Griffith so much that I later wrote a biography of him. I did not know Michael Collins; I missed knowing him, and that is a great regret. De Valera I knew. He ruined things at the time, and he destroyed Clann na nGael. I think Griffith was the greatest statesman we had: a greater statesman than the others, because be saw that unless there was something to fall back on, the Irish Insurrection would be a waste. Griffith liked to compare Ireland with Hungary, but Hungary was a different country altogether. It has an aristocracy and a military elite that was powerful and completely nationalistic, which Ireland had not; but by creating this myth and urging us to start our own Government, whether we got Home Rule or not, Griffith gave Ireland something to fall back on after the Insurrection. It would have been all over, as with other insurrections, if Griffith had not created the idea of Dáil Éireann. That was Griffith’s great contribution; but how shamefully he was treated.’ (p.16). [Cont.]

Further (Padraic Colum, ‘Life in a World of Writers’, in A Paler Shade of Green, ed. Hickey & Smith, 1972): ‘Ten or twelve years after his [Griffith’s] departure [from Ireland for South America at the end of 1897] when a name was needed to express a national policy he had enunciated, a young woman gave it to him - Sinn Féin, Ourselves. He took it as an inspiration, forgetting that William Rooney had written to him in Africa, “You are right - Sinn Féin must be the motto.”’ (Colum, Ourselves Alone: The Story of Arthur Griffith and the Origin of the Irish Free State, 1959, p.32; quotes in Joseph Sweeney, ‘Why “Sinn Féin?”’, Éire-Ireland, 6, 2, Summer 1971, p.36.) Colum further wrote ‘at the end of 1904 an enthusiastic lady, Miss Mary Butler, suggested the name “Sinn Fein” which Arthur Griffith, forgetting that he had used it in a letter from Africa instantly adopted.’ (op. cit., p.87; Sweeney, idem). Sweeney remarks that Colum’s two accounts are not equally firm about the date, and that Sinn Féin took its name as an organisation in 1905.

Richard Davis, Arthur Griffith and Non-Violent Sinn Féin (Tralee: Anvil Books 1974), writes that Arthur Griffith’s reaction against ‘the liberal-humanitarian ideal of racial equality’ stemmed from ‘his overreaction against the English and American nativist belief in the Irishman as a white nigger’ (pp.106, 107; cited in Emer Nolan, James Joyce and Irish Nationalism, Routledge 1995, p.21.)

David Cairns & Shaun Richards, Writing Ireland: Colonialism, Nationalism and Culture (Manchester 1988): Griffith’s response to The Shadow of the Glen [Synge], ‘Men and women in Ireland marry lacking love, and live mostly in a dull level of amity. Sometimes they do not – sometimes the woman lives in bitterness – sometimes she dies of a broken heart – but she does not go away with the tramp’ (The United Irishman, 1904) of which Griffith himself may have been the author (printed in Hogan and Kilroy, Mod. Irish Drama, Documentary History, II 1976). [E]conomic necessity forces this Norah to reject a loved but poor suitor in favour of a wealthy older man; the young man turns to drink; ten years after, Norah pleads with him to give up drinking; she rejects his advances as an insult her married status; the old woman to whom the suitor tells the narrative consoles him with the advice to give up drink and save money so that he will be financially attractive when the husband dies, [~78]. Moran, Griffith, Pearse, and even the Marxian Connolly, all regarded the basis of Irishness as ‘the Gael’ in contradistinction to the Celt, was masculine and antagonistic to the Anglo-Saxon, ‘the Gall’ [91]. [H]eavily dependent on writings of his friend and mentor William Rooney; while superficially resembling Moran’s, their ‘Gael’ was less exclusively Catholic than Moran’s; vigorously opposed parliamentarianism in 1900 elections, and then moderated towards pledge of withdrawal, [92]; position spelled out in The United Irishman in articles republished as The Resurrection of Hungary (1904), and also in The Sinn Féin Policy (1905). [Cont.]

Cairns & Richards (Writing Ireland [...], 1988) - cont.: Griffith argued that his was a tried policy which would leave links with the British monarchy to appease the Ulster unionists; Griffith’s commitment to economic development, his concern to work with Unionists and Protestants, and the absence of deference to clergy, exposed him to accusations of indifferentism, [93]; Griffith’s remedy of rural economic development and protectionism threatened the pastoral economy and its cultural foundation of familism; ardently supported Yeats’s Countess, but attacked Synge’s Shadow, demonstrating soundness on faith and morals independently of clerical deference, [94]; operated on the margin of Irish politics till the First World War [95]; limits of exploration and innovation lamented by, [103]; From 1917 to 1922 Sinn Féin was transformed from a party organisation under the virtual sole control of Arthur Griffith, to a unifying front organisation in which a host of nationalists and radicals coalesced, usurping ... UIL’s position as leader of the people-nation, [114]; Griffith, Treaty signatory and leader of the pro-Treaty majority within Sinn Féin, died August 1922, ten days before Michael Collins; their successors in the 1920s followed conservative economic and social policies ... with a continuing reluctance to see industrial development as suited to Irish needs ensur[ing] that the material and cultural basis of familism would be reproduced [116]; Arthur Griffith’s objections to the Abbey as unworthy to be self-style national theatre, [131].

Brian Maye, 70th Anniversary of the death of Griffith: A Commemorative Series of Two Articles, The Irish Times (11-12 Aug. 1992), celebrating the selflessness of the nationalist editor and first President of Ireland, who consistently refused salaries for his patriotic work. May urged, ‘Perhaps today his greatest relevance is the example of unselfish patriotism that he set.’

[Joep Leerssen, Remembrance and Imagination: Patterns in the Historical and Literary Representations of Ireland in the Nineteenth Century (Cork UP/Field Day 1996) - quotes Griffith’s several remarks on the plays of John Millington Synge (q.v.) and discusses in detail his reaction to the character of Norah Burke in In the Shadow of the Glen considered as a travesty of the Idealtypus of Irish womanhood and a false ‘personification of the average’ Irish countrywoman - pronouncing that ‘Norah Burke is a lie.’ (Leerssen, p.217.) In ensuing remarks, Leerssen lends substance to Griffith’s claim that ‘[t]he play has an Irish name, but it is no more Irish than the Decameron’ by tracing the motif of the ‘consolable widow’ in Boccaccio’s Decameron back to the Satyricon of Petronius Arbiter. Leerssen concludes: ‘In fact, Griffith demonstrates, Synge has done little else than to rehash the old and unedifying theme of the Widow of Ephesus.’ (Leerssen, p.217; see further under J, M. Synge - as infra.)

Further: Leerssen quotes extensively from exchanges between Griffith and Yeats in the debate of 1904-05 arising from Synge’s Shadow of the Glen (1903), which Griffith correctly identifies as a redaction of ‘The Wife of Ephesus’ fable in Boccaccio’s Decameron and Petronius’s Satyricon and quotes elements of the argument on both sides about the relation between art and nationality - where Griffith devastatingly echoes Yeats’s early contention that there is ‘no nationality without literature, no literature without nationality’ (Leersson, op. cit., p.218.) Extracts: ‘Griffith stated that In the Shadow of the Glen, with its Greek-Latin-Italian-French background, failed to answer Yeats’s own criterion of nationality: “Art is truth, and Mr. Synge’s play is not truth. it did not grow up on Irish soil and out of it.” (Quoted in Hogan & Kilroy, The Modern Irish Drama: A Documentary History, Vol. 2 [The Abbey Theatre: Laying the Foundations, 1902-1904, Dolmen Press 1976, p.82].

‘[...] For Griffith and his nativist Sinn Féin attitude, national was the opposite of foreign; for Yeats and his group, it was the opposite of provincial. For Griffith and like-minded nationalists to be a national theatre meant to cultivate homegrown, folk-steeped literature without foreign contamination; accordingly, to allow a foreign influence in the Abbey mean to abandon homegrown, domestic values for foreign frippery and to expose Ierland to the European blight of decadence. [...]

‘This pattern of conflicting ideas, the clash between national exclusivism and national enrichment, is of momentous importance in Irish developments. It was widespread at the times [...] and kept its hold over irish culture debate long after Griffth had become acting head of state in 1920 or Yeats had become a senator in 1922. Much of twentieth-century Irish history is dominated by the question of whether Ireland should seem its identity in an introspective or an extrovert mode, whether or not it should quarantine [219] itself from the vexations of modern life.

‘Griffith impugned the Irishness of Synge’s In the Shadow of the Glen because, despite its setting, it lacked folk authenticity and was tainted by a literarary, European provenance. Yeats and Synge argued against this that Sygne’s theme was a widespread one in orlall folk culture and that Synge heard it from an old man on the Aran Islands. That became the main focus of the debate as it flared up again in 1905, when In the Shadow of the Glen was revived, and with it the vexed question of Norah Burke’s morality and/or Irishness. Synge demanded that the United Irishman authenticate the play by printing the folktale as he had transcribed it; Griffith extricated himself by pointing out that the folktale was ‘essentially different to the play he sinsolently calls In a Wicklow Glen. [...] The original transcript of the story as told to Synge by Pat Dirane is extant.

[Here Leerssen cites its publication in Saddlemyer’s edition in Coll. Works: Plays of J. M. Synge [being vols. 3 & 4] (OUP 1968) and also cites Éilis Ní Dhuibhne’s (q.v.) tracing of its incidents in Irish folklore.]

‘In fact, then, the irony of the matter is that Synge, so far from being insufficiently attunded to the real peasantruy or wiwth true life in the west, failed to make the peasantry’s oral narrative sufficiently palatable to the Dublin theatregoers and their metropolitican, middle-brow demands of vraisemblance and biénseance [terminology of Gérard Genette invoked by Leerssen above]. it is not decadent European literarue which has an exclusive monopology on equivocal morality and a sense of the perplexities of life, nor is the folk tradition innocent and simplistic in its world-view. [...] A storyline used by Petronius [Satyricon] or Boccaccio [Decameron] may also be found on folktakes widely across the globe. [...; 221] These tales comprised precisely that sort of stuff which Griffith wanted to keep out of Ireland.

Further: Leerssen cites the arrival of an English translation of Decameron at the Blasket Islands ‘more or less under Griffith’s nose’ and the incorporation of its stories into the oral tradition of the island and concludes that ‘[i]t shows that the stock character of the aboriginal peasant, the timeless Ireland, is flawed precisely in it dehistorizing reflex, its tendenccy to see the Irish peasantry as uninvolved in a historical dynamics.’ (p.221; end section.)

Bibl. incls. Declan Kiberd, Synge and the Irish Language (Macmillan 1979), pp.151-75; spec. pp.152-59; James Stewart, ‘Boccaccio in the Blaskets’, in Zeitschrifte für Celtische Philologie, 43 (1989), pp.125-40; Éilis Ní Dhuibhne-Almqvist, ‘Synge’s use of popular material in The Shadow of the Glen’, in Béaloideas, 58 (1990), pp.141-80; Bo Almqvist, ‘The mysterious Michael O Gaoithin, Boccaccio and the Blasket Tradition’, in Béaloideas, 58 (1990), pp.75-140.

[ See further examples of Griffith’s commentary on Synge, Yeats and Joyce under those authors names in RICORSO. ]

[ top ]

Fintan O’Toole reply to Brian Maye, ‘Second Opinion’ column [idem.], quoting extensively to show that Griffith’s ideological outlook was an ambiguous legacy to Ireland, and that he was in many ways ‘a repugnant figure’, the enemy of other races, working classes, and no friend to the Rights of Man. During the Lock-Out of 1913, he wrote an introduction to Mitchell’s Jail Journal, praising Mitchell because ‘the liberty he fought for in Ireland was [...] just the sort of liberty the slave-owning Corcyraeans asserted against Rome, and the slave-holding Americans wrung from England.’ Griffith wrote that Mitchell needed no excuse for ‘refusing [recte ‘declining’] to hold the negro his peer’ [also cited in Luke Gibbon, op. cit. Transformations in Irish Culture, Cork/FDA 1996]. O’Toole quotes further, presumably from the same source, ‘The right of the Irish to political independence never was, is not, and never can be dependent upon the admission of equal right in all other peoples. It is based on no theory of, and dependent in nowise for its existence or justification on, the ‘Rights of Man’ [...] He who holds Ireland a nation [...] thereby no more commits himself to the theory that black equals white, that kingship is immoral or that society has a duty to reform its enemies than he commits himself to the belief that sunshine is extractable from cucumbers.’ In the United Irishman, Griffith fulminated against newspapers supporting Dreyfus as ‘the impotent ravings of a disreputable minority which is universally regarded as a community of thieves and traitors [...] rags which have nothing behind them but the forty or fifty thousand Jewish usurers and pickpockets in each country and which no decent Christian ever reads except holding his nose as a precaution against nausea.’ In support of the attacks on Jews in Limerick, he wrote in his paper, ‘the Jews of Ireland have united, as is their wont, to crush the Christian who dares to block their path or point them out for what they are [...] usurers and parasites of industries [...] the Jews of Ireland is in every respect an economic evil [...] &c.’ Griffith was viciously hostile to Larkin whose reflection on the Strike was that ‘whatever causes the area of manufacturing to contract in Ireland dangerously affects the future as well as the present prosperity of the country.’ Having initially supported Yeats and Lady Gregory, he attacked In the Shadow of the Glen on the grounds that no Irish woman would ever behave as Nora does, and went to far as to write an alternative drama called ‘In a Real Wicklow Glen’, in which the wife stays to bear numerous children and in time learn to love her sour old husband. O’Toole concludes, with a comparison to Mussolini, and adds that it is as well Griffith died when he did before he could put his politics into effect as Head of State (‘The Other Side of Arthur Griffith’).

Further: O’Toole also cites the discussion of the weaknesses of the anti-Union economics formulated by George O’Brien, nationalist history, in several works around 1918-1920 (e.g., The Economic History of Ireland in the Eighteenth Century), in David S. Johnson and Liam Kennedy in ‘Nationalist historiography and the decline of the Irish economy, George O’Brien revisited’, in Ireland’s Histories, Aspects of State, Society and Ideology, ed. Sean Hutton and Paul Stewart (1991), pp.11-35. And see especially p.12, regarding ‘the thesis that Ireland’s economy had languished under the Penal Laws; that it had flourished under Grattan’s parliament; and that this prosperity had been destroyed by the Act of Union. Indeed, in the stronger version of this thesis, as expounded by Arthur Griffith, for example, the Union had been expressly designed by England to impoverish Ireland (see Resurrection of Hungary, A Parallel for Ireland, 3rd ed. Dublin: Duffy 1918, pp.118, 138). These ideas could in fact be traced back to Daniel O’Connell and the Repeal movement.’ The authors also cite T. K. Daniel, ‘Griffith on his noble head, the determinants of Cumann na nGaedheal economic policy 1922-23’, in Irish Economic and Social History, 3 (1976), pp.55-65. Note Dr. O’Connor Lysaght, in Hutton & Stewart, eds., op. cit. p.40, From 1905 Griffith’s Sinn Féin made explicit the Republican economic and social programme, with some success, but it overstretched its resources (among other initiatives, it tried to produce a daily paper) and after 1910 it could do little more than make propaganda. [...] In 1907 James Larkin began the lasting organisation of Irish unskilled workers, founding the ITGWU [...] Griffith accused Larkin of being a British saboteur of the remaining Irish businesses and thereby lost his party’s left wing. A distinct, independent, working-class interest was established. (p.40).

Liam Kennedy, ‘The Union of Ireland and Britain, 1801-1921’, in Colonialism, Religion and Nationalism in Ireland (IIS/QUB 1996); quotes Griffith, ‘Under the operation of the infamous Act, one by one all her great industries, except linen, were again destroyed or reduced to skeletons of their former greatness.’ (‘Economic Oppression of Ireland’, in Appendix 3, ed., The Resurrection of Hungary, Dublin 1914; Kennedy, p.55, with remarks, ‘Griffith stresses the benefit of protectionism, despite the small size of the Irish market, and is equally uncritical in his exaggerated assessment of the extent of Irish natural resources. By comparison with the earlier Repeal arguments, this is fairly crude stuff.’ (ibid.)

[ top ]

Mark Duncan, ‘Ireland’s Lord Lieutenant: ‘... a fount of all that is slimy in our national life ’ (RTE/CenturyIreland 2015): ‘[...] The energy and seeming restlessness of Ishbel, or Lady Aberdeen, made her appear almost ubiquitous: she was indefatigable in her championing of charitable causes, social reform and home-grown Irish industrial development. Her philanthropic impulses led her to spearhead, amongst other things, an anti-tuberculosis campaign and, in the wake of the Dublin housing crisis of 1913-14, to promote improved town planning for the city and elsewhere. A supporter of women’s suffrage (though unaligned to any Irish suffragist organisation) she didn’t confine her activism to Ireland, being twice elected president of the International Congress of Women. [Ftn. The Irish Citizen claimed that the suffragette cause in Ireland was denied the support of a Suffragist Lord Lieutenant because of the ‘theory of impartiality of the King ’s representative ’ - Irish Citizen, 9 January 1915.] / Impressive as all this undoubtedly was, it did nothing to insulate Ishbel - or her husband - from criticism, and may even have helped to fuel some of it. / For all that it was associated with worthy causes and for all that it was supportive of the Irish home rule cause, the Aberdeen viceroyalty was mercilessly derided by its opponents. If unionists were instinctively hostile on the grounds of the couple ’s Home Rule sympathies, socialists and advanced nationalists were no less sparing in their scorn.

Mark Duncan, ‘Ireland’s Lord Lieutenant [....]’, 2015) - cont.: ‘Arthur Griffith, the founder and editor of Sinn Féin, was one of the more unforgiving and constant of critics, believing the Aberdeen ’s benevolence to be a mere mask which concealed the hard realities of British government in Ireland. Moreover, Griffith argued that the maintenance of a ‘mock British King and a mock British Court in Ireland ’ was corrupting. ‘The British Lord Lieutenant’ he wrote as early as 1906, ‘is maintained in Ireland as a fount for all that is slimy in our national life. ’ (Sinn Fein, 4 August 1906; quoted in Patrick Maume, ‘Lady Microbe and the Kailyard Viceroyalty: The Aberdeen Viceroyalty, Welfare Monarchy, and the Politics of Philanthropy, in Peter Gray & Olwen Purdue eds., The Irish Lord Lieutenancy: c. 1541-1922 (2012) p. 207.

Mark Duncan, ‘Ireland’s Lord Lieutenant [....] ’, 2015) - cont.: ‘As it happened, Griffith would play a part in hastening the eventual departure of the Aberdeen ’s from Ireland after his own newspaper precipitated a public furore when it disclosed details of a private letter sent by Ishbel to the editor of the Freeman ’s Journal on the need to protect against unionist control of the Irish Red Cross. In 1915, in the very first issue of Nationality, the newspaper he founded to succeed those that had been suppressed under war-time censorship, he stated that: ‘A Viceroy, a separate Executive and separate Law Courts remain to attest to the disaffected England ’s admission that Ireland is an alien nation.’ (Nationality, 1:1, Saturday 19 June 1915.)

Mark Duncan, ‘Ireland’s Lord Lieutenant [....] ’, 2015) - cont.: ‘Griffith’s criticisms of the institution continued unabated, however: for him, the viceroyalty constituted a cornerstone of Britain’s imperial architecture in Ireland that needed to be dismantled in its entirety. He suggested that the office at once represented Ireland’s separateness and subjugation. In 1915, in the very first issue of Nationality, the newspaper he founded to succeed those that had been suppressed under war-time censorship, he stated that: “A Viceroy, a separate Executive and separate Law Courts remain to attest to the disaffected England’s admission that Ireland is an alien nation.” (Nationality, 19 June 1915.) That Griffith focussed on the symbolism of the office is significant. As the viceroyalty of Lord Aberdeen gave way to that of Lord Wimborne, there really was little more to it. In the pithy assessment of the historian Theo Hoppen, the Lord Lieutenant had become ’an irrelevance ignored by everyone with any influence on events.’ (K. Theodore Hoppen, A Question None Could Answer: ‘What Was the Viceroyalty For? 1800-1921’, in Peter Gray and Olwen Purdue eds., The Irish Lord Lieutenancy: c. 1541-1922 (2012), p. 135.) [Available online as pdf; accessed 26.04.2021.)

[ top ]

Colum Kenny, ‘Friend or foe? How WB Yeats damaged the legacy of Arthur Griffith [...]’, in The Irish Times (26 Jan 2021): Griffith claimed to have given W. B. Yeats the ending of his Cathleen Ni Houlihan (1902) yet Yeats speaks of Griffith ‘staring in hysterical pride’ in “Muncipal Gallery Revisited”. Griffith declined to publish WBY’s response to a reviewer who accused him of wishing to substituting Cuchulain for Christ, telling Yeats: ‘Anything we write must show kindly dignity not vexation - They are only untaught children’, and -the attack on reviewers leaves an impression of fretfulness’. Kenny explores the uneven relationship between the two in which Griffith promotes the Yeats family and publishes several Yeats’s writings in a United Irishman including a supplement with Yeats’s play Where There is Nothing (Nov. 1902) but parts ways over Synge’s Playboy and the direction of Irish theatre.

Colum Kenny (‘Friend or foe? How WB Yeats damaged the legacy of Arthur Griffith [...]’, IT, 26 Jan. 2021): ‘In 1916 Griffith launched one of those savage verbal assaults to which he sometimes gave vent, attacking Yeats as both an imperialist and imperious, querying his knowledge and scholarship. But later, as president of the new Dáil, he nominated Yeats to represent Ireland at a convention in Paris concerning the Irish “race”, and Yeats admitted that he would be tempted to accept a possible offer to become minister for fine arts in Griffith’s government.[...] The use of the word “hysterical” is inexplicable. It has helped to sideline in history the once central figure of Griffith. [...] As early as 1903, in Griffith’s United Irishman, the socialist Fred Ryan had taken issue with Yeats for depicting nationalist fervour in a way that Ryan claimed tried to define advanced nationalists clinically and thus reduce patriotism to pathology. Yeats came to articulate an ostensibly gendered theory that Ireland had long pursued fixed ideas until “at last a generation is like an hysterical woman who will make unmeasured accusations and believe impossible things”. One wonders to what extent this was a projection of his earlier confused and obsessive fixation on Maud Gonne, who rejected him in favour of the militant republican John MacBride.’ (See Irish Times - online; accessed 02.05.2021.)

[ top ]

Quotations

Resurrection of Hungary (1904; 3rd ed. 1918, with new preface). ‘Sixty years ago, and more, Ireland was Hungary’s exemplar. Ireland’s heroic and on-enduring resistances to the destruction of her independent nationality were themes the writers of Young Hungary dwelt upon to enkindle and make resolute the Magyar people ... Times have changed, and Hungary is now Ireland’s exemplar.’ (Pref. 1st ed.). ‘Irish Parliamentarianism, born of the Act of Union and based upon admission of English right over Ireland, was inherently vicious. It constituted not a national expression, but a national surrender. It was the acceptance of moral and constitutional right in another country to shape our destinies; and whither it led the Irish people – to the attempted renunciation of their national past and their national future – to provincialism, partition, and foreign conscription – was whither it tended by the law of its being.’ (Preface, 3rd ed.) Griffith identifies O’Connell’s attempt to set up a Council of Three Hundred in Dublin, and with it the ‘Arbitration Courts’, as the ‘one statesman-like idea’ of his life. (Cited in The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing, gen. ed. Seamus Deane, Vol. 2.)

| Preface to John Mitchel’s, Jail Journal (Dublin: Gill 1913) |

|

|

Education: ‘The secondary system of education in Ireland … was designed to prevent the higher intelligence of the country performing its duty to the Irish State. … in Ireland secondary education causes aversion and contempt for industry and ‘trade’ in the heads of young Irishmen, and fixes their eyes, like the fool’s, on the ends of the earth. The secondary system in Ireland draws away from industrial pursuits those who are best fitted to them and sends them to be civil servants in England, or to swell the ranks of struggling clerkdom in Ireland.’ (The Sinn Fein Policy [n.d.], speech before National Council, 28 Nov. 1905; quoted in Roy Foster, Paddy and Mr Punch, 1993, p.312).

Race & Empire: ‘[Griffith] considered it outrageous that Irleand should be treated as a colony because to do so was to put an ancient and civilised European people on the samae level as non-white colonial subjects in Africa or Asia.’ (Joseph Cleary, ‘Misplaced Ideas?’, in Ireland and Postcolonial Theory, ed. Clare Carroll & Patricia King, Notre Dame UP 2003, p.27; quoted in Richard Pine, The Disappointed Bridge: Ireland and the Post-colonial World, Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing 2014, p.4.)

Withdraw your member: ‘That we call upon our countrymen abroad to withdraw all assistance from the promoters of a useless, degrading and demoralising policy until such time as the members of the Irish parliamentary party substitute for it the policy of the Hungarian deputies of 1861, and refusing to attend the British parliament or to recognise its right to legislate for Ireland remain at home to help in promoting Ireland’s interests and to aid in guarding its national rights.’ (Proposal of 16 Oct. 1902 at Cumann na nGaedheal convention, reported in United Irishman, 1 Nov. 1902; cited in F. S. L. Lyons, Ireland since the Famine, 1971, p.248.) Note Lyons’s comment, ‘The curious point about this resolution is that a perfectly respectable Irish pedigree could have been found for it without confusing honest nationalists with obscure Hungarian analogies. O’Connell had toyed briefly with such a policy in 1843, Thomas Davis had advocated it on behalf of the Repeal Association in 1844, and nearly forty years later it was urged on Parnell by his left wing in the critical summer of 1881’; see also under Andrew Kettle.

Free-thinking: ‘This cocky disparagement of the work of modern thinkers is characteristic of the shoddy side of the Irish revival. According to this gospel we are to keep our eyes fixed on the Middle Ages - and then wonder we are decaying ... The world outside has been thinking and growing, Ireland preserves her picturesque ignorance - which her smart young men, who know better themselves, tell her is more sacred than the wisdom of an infidel world - and Ireland emigrates. We require the breath of free thought in Ireland.’ (United Irishman, 25 July 1903; quoted in Tom Garvin, ‘Patriots and Republicans: An Irish Evolution’, in Ireland and the Politics of Change, ed. William J. Crotty & David A. Schmitt, London: Routledge 1998, [Chap. 8.] p.149.)

Irish neutrality: Sinn Féin (8 August, 1914): ‘Ireland is not at war with Germany […]. The spectacle of the National Volunteers with English officers at their head, and the Union Jack floating proudly above them, “defending” Ireland for the British Government, may appeal to the gushing eyes of Mr John Redmond, but his eyes are not likely to be blessed with that apotheosis of slavery [… .] Who can forbear admiration at the spectacle of the Germanic people, whom England has ringed round with enemies, standing alone and undaunted and defiant against a world in arms? If they fall, they will fall as nobly as ever a people fell, and we the Celts may not forbear to honour a race that knew how to live and how to die as men.’ (Cited in Maurice Headlam, Irish Reminiscences, 1947; see under Headlam, q.v.)]

[ top ]

Evil influences?: ‘The Three Evil Influences of the century are the Pirate, the Freemason, and the Jew’ (United Irishman, 23 Sept. 1899): ‘‘[A]ll countries in all Christian ages he has been a usurer and a grinder of the poor ... The jew in Ireland is in every respect an economic evil. He produces no wealth himself – he draws it from others – he is the most successful seller of foreign goods, he is an unfair competitor with the rate-paying Irish shopkeeper, and he remains among us, ever and always alien.’ (The United Irishman, April 23rd 1904.)

Further: ‘[The Irish ought to] cherish that feeling of hatred as their most valued possession, as the rock upon which the edifice of their nationality can only be built securely.’ (United Irishman, 5 March 1904, p.5; the foregoing quoted in Joe McMinn, ed., The Internationalism of Irish Literature and Drama (Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1992), ftn., p.354 [q. author].

Note: the article is cited in Roy Foster, ‘Varieties of Irishness’, in Maurna Crozier, ed., Cultural Traditions in Northern Ireland: Varieties of Irishness, [with] proceedings of the Cultural Traditions Cultural Traditions Group Conference, IIS 1989, p.16); also in Foster, Paddy and Mr Punch (1993) with comment: ‘anti-semitic ravings of Arthur Griffith’s United Irishman [...] ... make chilling reading; derived directly from anti-Dreyfus campaign in France, to which Griffith was violently committed’ (p.32). See also full extracts from his anti-semitic editorials arising from the Limerick pogrom rep. in Dominic Manganiello, The Politics of James Joyce (London: Routledge 1980).

Irish National Theatre: ‘We look to the Irish National Theatre primarily as a means of regenerating the country. The Theatre is a powerful agent in the building up of a nation. When it is in foreign and hostile hands, it is a deadly danger to the country [...] In the Ireland we foresee it will be an extremely dangerous thing to tell an Irishman that God made him unfit to be master in his own land.’ (United Ireland, 8 Nov. 1902; quoted in Patrick Dowdall, ‘“What Ish My Nation?: W.B. Yeats and the Formation of the National Consciousness’, in Vogelview [Journal of Eric Voegel Soc.], 12 Nov. 2019 -available online; citing in Robert Hogan & James Kilroy, The Abbey Theatre: The Years of Synge [1905-09] (Dublin: Dolmen Press 1976, pp.37-38.)

Playboy of the Western World: Griffith editorialised J. M. Synge’s Playboy vituperatively in 1907: ‘a vile and inhuman story told in the foulest language we have ever heard from the political platform.’ (Q. source.) He further wrote: ‘Mr Synge’s Nora Burke is not an Irish Nora Burke [...] She is a Greek, a Greek of Greece’s most debased period, and to dress her in an Irish costume and call her Irish is not only not art, but it is an insult to the women of Ireland.’ (Quoted in Edward Stephens & David Greene, J. M. Synge [1959], p.182; quoted in Nicholas Grene, ‘Reality Check: Authenticity from Synge to McDonagh’, in Irish Studies in Brazil, ed. Munira H. Mutran & Laura P. Z. Izarra, Sao Paolo: Associação Editorial Humanitas 2005, p.75.) Note also that Stephens calls him ‘Synge’s nemesis’, in J. M. Synge (1959). [See further remarks by Griffith on works of J. M. Synge - as infra.]

Racism?: ‘The soul that is born in us, and the soul that we are born in’ (Sinn Féin, 1913; given in The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing, 1991, Vol. 2 p.1003.) Note also his contention that ‘no excuse [is] needed by an Irish nationalist declining to hold the negro his peer’; and further, ‘the right of the Irish to political independence never was, is not, and never can be dependent on the admission of equal right in all other peoples’ (both cited in Luke Gibbons, Transformations in Irish Culture, Field Day/Cork UP 1996, pp.105, 105-06.)

On Jewish immigration: ‘No thoughtful Irishman or Irishwoman can view without apprehension the continuous influx of Jews into Ireland and the continuous efflux of the native population [...] in their place we are getting strange people, alien to us in thought, alien to us in sympathy, from Russian, Poland, Germany, and Austria - people who come to live amongst us but who never become of us.’ (United Irishman, 23 Jan. 1904, p.5; quoted in Micheal Laffan, ‘Bloomsyear’, in Voices on Joyce, ed. Anne Fogarty & Fran O’Rourke, UCD Press 2015, p.28.) Lafffan goes on to cite Griffin’s remark that ‘the Jew comes here and lives, in nine cases out of ten, by usury’, and his satisfaction that outcome of Fr. Creagh’s anti-Jewish campaign in Limerick had been ‘to transfer the custom of the Limerick working people from the Jews to the Christians’ (Idem.)

[ top ]

References

J. E. Doherty & D. J. Hickey, A Chronology of Irish History Since 1500 (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1989); Sinn Féin, developed 19 May 1908, absorbing Dungannon Clubs, under Bulmer Hobson, the National Council, and Cumann na nGaedhael; title suggested by Mary Lambert Butler; first President, John Sweetman with Griffith and Hobson as Vice-Presidents; mbrs. incl. W. T. Cosgrave, Sean MacDiarmada, Countess Markievicz, and Sean T. O’Kelly; newspaper organ, Sinn Fein (1906-1914), to be replaced by An Phoblacht; economic theory influenced by Friedrich List, 1908; ‘declared object ... to make England take one hand from Ireland’s throat and the other out of Ireland’s pocket’ (Griffith); C. J. Dolan, formerly IPP MP, lost N. Leitrim by-election as Sinn Fein candidate, proposing withdrawal from Westminster if elected, 1908; challenges gained support with anti-conscription campaign; 1916 inaccurately described as ‘Sinn Fein Rebellion’ by authorities; reorganised in 1917 under presidency of Eamon de Valera; constitution adopted at Ard Fheis, 25 Oct. 1917 undertaking to convoke a Constituent Assembly; boycotted Irish Convention, 1917-18; arrest of 100 mbrs. for ‘German Plot’; Manifesto to the Irish People (‘Sinn Fein stands less for a political party than for a nation; it represents the old tradition of nationhood handed on from dead generations; it stands by the Proclamation [of 1916]’); 73 seats in general election, 1918; SF MP’s met to form first Dail Eireann, 19 Jan. 1919; Declaration of Independence;, and Democratic Programme; Treaty, Dec. 1921; Sinn Fein membership refused to recognise Irish Free State; 12,000 interned until 1924; de Valera walks out of Dail when his motion concerning Oath of Allegiance; opposed by Fr. Michael O’Flanagan, and rejected by 223 votes to 218; won single seats in E. Cork, N. Dublin, Kerry, N. Mayo and Waterford constituencies, 1927; outlawed in 1931, and 1936; IRA campaign, 1957; lost its four seats in 1961 election; revitalised under Tomás Mac Giolla (and Roy Johnston), 1965; stewards to NICRA; formation of Provisional IRA and Provisional Sinn Fein, Jan. 1970 under first President, Ruadhrí Ó Bradaigh; PSF, HQ Kevin St., organ An Phoblacht; Official Sinn Fein, Gardiner St., organ The United Irishman.

ODNB cites Transvaal, 1896-99; ‘the real creator of the autonomous Irish state.’

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 2: select The Resurrection of Hungary [354-49], and his obituary ‘The Death of Frederick Ryan’ with its sequel in response to Skeffington [1002-04], in Sinn Féin, 13 Apr 1913. Seamus Deane, ed., Griffith’s The Resurrection of Hungary (1904) draws a rather quaint parallel between the respective positions Hungary and Ireland within the Austrian and British Empires. The pertinence or otherwise of the analogy does not matter in the least now and did not matter a great deal then. The comparison was rhetorical device to stimulate the public into thinking of an alternative to Home Rule and to make economic sufficiency a priority of this new departure. According to Griffith, the legitimacy of the Irish claim to self-government had been conceded in the Renunciation Act of 1783. Since then Britain had denied that legitimacy and had promote futile rebellion in the cause of separatism in order to provide an excuse for reducing Ireland to economic servitude, &c.’, 213. For Griffith’s response to Skeffington’s umbrage at his denial of Frederick Ryan the title of a nationalist, see Fred Ryan; ‘.. we mean the soul into which were born and which was born into us ...’, 1004. References, compared with William O’Brien as being able to cease the pursuit of the elusive and meaningless Home Rule [Deane, ed.], 212; [213 see above], [oblique disparagement in F. H. O’Donnell, 337n; regarded legislative independence of 1782 as a sham, 344n; [fall of Parnell to rise of Sinn Féin, 347n]; Abbey movement having to contend with populist aspirations orchestrated by The United Irishman, 562; friend of James Starkey/Seamus O’Sullivan, 781; Yeats, ‘Griffith staring in hysterical pride’ (Municipal Gallery Revisited’), 824; Kettle distances himself from Griffith’s economic protectionism, 966n; influence on Griffith of German nationalist and protectionist Freidrich List 1789-1846, 967n; [988n err.], [United Irishman (1899), ed., 1026]; [biogs. ?err.], 1218 [biog. Seamus O’Kelly], 1219. FDA2, ‘outwitted by Lloyd George’.

Libraries & Booksellers

Belfast Public Library holds The Resurrection of Hungary (1918); ed. of Thomas Davis (1922). Emerald Isle Books, 96, lists: The Resurrection of Hungary: A Parallel for Ireland (Dublin: James Duffy 1904), 99pp.; The Resurrection of Hungary: A Parallel for Ireland, containing new preface by the author, 20 January 1918, with his address at the first Convention of Sinn Fein outlining the Sinn Fein programme [3rd edn.] (Dublin: Whelan 1918). Hyland Catalogue (Cat. 214), lists Arthur Griffith and Michael Collins, Commemoration Booklet (1922) [contribs. by Padraic Colum, Gogarty, Ó Conaire, Shane Leslie, etc.]

[ top ]

Notes

James Joyce conducted a running commentary on The United Irishman in his letters to Stanislaus from Trieste, calling his editorial outlook ‘the pap of racial hatred’. (Letters of 15 Sept. 1906, in Letters, Vol. II, p.167; also in Richard Ellmann, ed., Selected Letters, Faber 1975, p.111.)

|

[ top ]

Jewish pogrom in Limerick: The pogrom is said to have been occasioned by the attempt of two Jewish brothers to undersell local furniture makers with products derived from American prison labour, and that the Mayor of Limerick wrote to the London Times repudiating charges of anti-Semitism. [Check sources.]

‘Ireland’s Case Against America’ (on growing anti-Americanism): ‘In an effort to bridge this trans-Atlantic information gap, we provide excerpts from the Irish media which are hyperlinked to their full-length sources on the web sites of the major Irish news dailies and Irish television. This is done in the manner of the Irish patriot Arthur Griffith, who, in his newspaper “Scissors and Paste”, evaded British censorship by sampling articles from the uncensored press and then juxtaposing them so that readers could draw their own conclusions.’ [See online.]

Pseud. “Seán Ghall”? Griffith is sometimes cited as most likely owner of the pseud. “Sean Ghall” subscribed to the Preface of William Bulfin, Rambles in Erin (1907) and the obit. for Ellen Downing in United Irishman (1902), &c. See, however, the conjectural identification with P. J. Kearney in a bibliography of critical writings on Sean O’Faoláin - probably hostile and ironic, and possibly an assumption of the pseud. by another than its original user (i.e., Griffith). [But note signatories on Griffith Ave. Memorial, infra.]

Tarahan dynasty: Arthur Griffith and Maud Gonne walked on Tara Hill, Christmas Day 1900, inspecting damage done to the site by the excavators seeking the lost ark of the covenant. [The title of this note is taken from the “Roderick O’Connor” episode Finnegans Wake of James Joyce. BS]

Irish finality?: Note the different versions of Griffith obiter dictum on the Treaty: a) Treaty ‘It has no more finality than we are the final generation on earth’ [as supra, Life]; b) ‘It has no more finality than we are the final generation of Irishmen’ (quoted in Richard Kain, Dublin in the Age of William Butler Yeats and James Joyce [1962] Newton Abbot: David Charles 1972, p.137.

Griffith Avenue: “Memorial to Arthur Griffith - a new thoroughfare, name Griffith Ave. , in the parish of Fairview” [pamph.], signed Sean Gall, P. J. Ingoldsby, L. Rooney, J. F. Shouldice, Chas. Moran, P. J. Duffy, Mary Saurin, Michael O’Loingsigh, Margaret Wheatley. 24 Waverley Ave., Fairview, Dublin. 5th October 1927. (Held in William O’Brien Collection of National Library of Ireland as PO 115, Item. 56.)

Portraits: See portrait of Arthur Griffith by Leo Whelan (Anne Crookshank, Ulster Mus. Cat. 1965) Also an oil portrait by Sir John Lavery. There is also bronze bust by Arthur Power, 1922 [NGI].

[ top ]