Life

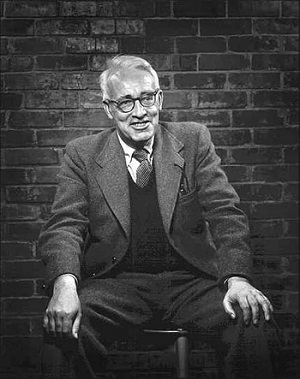

| [pseudonym of Michael O’Donovan; occasional pseud. “Ben Mayo”]; b. 17 Sept. 1903, at 84 Douglas St., Cork; ‘an only child’ and ‘a mother’s boy’, son of Minnie O’Connor, a household servant, who was raised in an orphanage and later worked for the Barry family in Cork, forming strong attachments to the dg. Alice, and to Mr. Barry (who may have been in love with her); m. ‘Big Mick’, a Corkman serving in Munster Fusiliers, often away with the British Army, and given to alcoholic bouts and domestic violence; born during one of his father’s absences; he and his mother ‘never happier’ than when he was away; a grandmother was a native Irish speaker; family moves to more squalid part of the city with the return of his father; ed. St. Patrick’s Boys National School (CBS), and taught by Daniel Corkery on his arrival as a teacher in 1912; moves to North Monastery (CBS), 1913-1916; after a period at the Technical (Trade) College; starts working for on Great Southern & Western Railway, aged 14; reads widely in public library, guided by Corkery, who introduces him to Irish language and culture; joins IRA and serves in the Civil War as a Republican soldier-cum-war reporter (‘I took the republican side because it was Corkery’s); |

| arrested and imprisoned at Gormanstown, 1922, reading voraciously while teaching Irish and German during internment; perfected his Irish grammar; released shortly before Christmas, 1923 (‘I was tired of war and wanted to go home’); Corkery secured him a job in the Carnegie Libraries through Lennox Robinson, progressing from the North of Ireland to Dublin; appt. librarian in Sligo, then Wicklow; introduced to George Russell (AE) by Geoffrey Phibbs, and encourged by him; introduced in turn to Yeats and Lady Gregory; begins publishing in The Irish Statesman as [pseud.] “Frank O’Connor” with a translation, ‘Suibhne Geilt Aspires’, and subsequently contributed some 75 pieces; studies Old and Middle Irish, and seeks assistance on linguistic matters from Daniel Binchy, becoming close friends while serving as librarian in Wicklow, using his family mother’s name; meets Yeats through Russell; moves back to Cork, contrary to Russell’s advice, serving as Cork City Librarian 1925-28; was involved in Cork Drama Group and organised readings of drama and poetry at the library; split with Corkery on being told ‘ther are many things more important in life than literature’ - to which he replied, ‘I knew there weren’t because if there were, I should be doing them’; moved to Dublin and was appt. Librarian to Pembroke [Carnegie] Library, Ballsbridge, 1928-38; became a founder-member of Irish Academy of Letters and Medals with Yeats, AE and others, Sept. 1926; |

| goes out with Nancy McCarthy for six years - with a frustrating visit to Dunfanaghy in 1929 - before she breaks it off to marry another man, 1930; following the demise of Irish Statesman, his story “Guests of the Nation” appears in Atlantic Monthly, 1930; issues his first collection as Guests of the Nation (1931), a generally romantic account of the period, excepting the title story; speaks up at the Rotunda Meeting for Jim Gralton, the Roscommon socialist deported to America by the Fianna Fáil Government, 1932; publishes translations from Irish as The Wild Bird’s Nest (1932); appt. Abbey theatre director in succession to Brinsley MacNamara, 1935; issues Bones of Contention (1936), a second story collection; issues Three Old Brothers (1936), poetry collection; issues The Saint and Mary Kate (1936), a novel; gives graveside oration for George Russell, 1935; writes biography of Michael Collins as The Big Fellow (1937), expressing disaffection from the successors of the independence movement; resigns from Abbey Board on the death of Yeats in the belief that there is no longer any place for the writer in public life (‘At once I resigned from every organisation I belonged to and sat down at last to write’); with Hugh Hunt, writes The Invincibles: A Play in Seven Scenes (Abbey Th. 18 Oct. 1938); |

| m. actress Evelyn Bowen, a Welsh actress, 11 Feb. 1939, at Chester Registry Office following her divorce in Feb. 1939, and settles at Woodenbridge, Co. Wicklow; contrib. 8.“Letters on Theatre Censorship” to The Irish Press (Monday, 22 May 1939); a son Myles O’Donovan b. 18 July 1939; appt. founding poetry editor of The Bell, 1940, to which he contributes stories and poetry incl. his translation of The Midnight Court by Brian Merriman - and participated in The Irish Times correspondence arising from its censorship, incl. letters from James Hogan [Censor]; issues Dutch Interior (1940), a second novel; banned in Ireland, copper-fastening his popular association with sexual licence and anti-clericism; campaigns for preservation of Irish cultural monuments; a dg. Liadain [O’Donovan, later Cook], b. 27 Nov. 1940; O’Connor debarred from radio work in the 1940s in view of policy of neutrality; issues Irish Miles (1941), a travel book in Ireland; maintains a close friendship with Fr. Jim Traynor [part-model for Fr. Fogarty of ‘pugilistic Irish face, beefy and red and scowling’ in several stories]; issues Crab Apple Jelly (1944), stories; begins long working friendhip with William Maxwell, editor of New Yorker, 1945; meets Joan Knape, working for the BBC in London; Joan moves to Dublin with their infant son Oliver (b. June 1945), 1945; forms menage-à-trois, with his mother also in residence, at Sandymount, Dublin, 1945; Evelyn gives birth to Owen O’Connor, June 1946; marital breakdown and departure of Evelyn to Wales with children Myles, Liadain and Owen, 1949; |

| issues The Common Chord (1947), stories, banned in Ireland; involved in custody proceedings; contributes pieces to New Yorker, incl. the essay “Ireland” (1949); issues Traveller’s Samples (1951), stories, banned in Ireland; writes on Ireland for US magazine Holiday, giving an account of the murder of illegitimate babies by Irish girls, a dozen of whom he had seen being sentenced in a single morning at Green St. Court, and later claims that the Irish News Agency sought to discredit him for this reason; accepts lecturing posts in America, 1951 [var. went to America 1952]; while lecturing at Harvard he meets Harriet Rich, a student and dg. of Baltimore businessman; denounced as an ‘anti-Irish Irishman’ in Irish Press editorial (15 Dec. 1949), arising from his article “Ireland” in Holiday (6 Dec. 1949); m. Harriet, 5 Dec. 1953 - following his divorce; returns on frequent visits to Ireland from 1956; issues Domestic Relations (1956), nostalgic stories, some related by Cork boy Larry, and The Mirror in the Roadway (1956), a collection of criticism; a dg. Hallie-Og, b. 25 June 1958, Dublin; issues Kings, Lords and Commons (1959), translations in the form of an anthology, with an introduction acknowledging the help of Yeats and noting the poet’s borrowings from same, but including his translation of Merriman and therefore banned in Ireland; returns to Ireland 1960; |

| issues The Lonely Voice (1962), a study of the short story genre, emphasising the isolation of the protagonist-narrators; proposes the motion ‘That Irish Censorship is Insulting to Irish Intelligence’ at the Hist [Historical Soc., TCD], 14 Feb. 1962; opposed by Justice Kevin Haugh; received hon. doct. at TCD, July 1962, and appt. lecturer in English, TCD, 1963; gives the oration at the W. B. Yeats centenary celebrations, Sligo, 1965; continues writing reviews for New York Review of Books; d. 10 March 1966, Dublin; bur. Dean’s Grange, Dublin, with verses from The Herne’s Egg of W. B. Yeats on his gravestone; his funeral oration was delivered by Brendan Kennelly; post-hum. publ. of The Backward Look (1967), based on his lectures, and amounting to a synthesising of Irish and Anglo-Irish traditions, using a title-phrase taken from Ferguson; his remarks about the absence of a chair in Anglo-Irish literature in Ireland in the same resulted in the establishment of such a chair at UCD; ed. with David Greene, A Golden Treasury of Irish Verse Poetry AD 600-1200 (1967); posthum. publication of Collection Three (1969), stories and specially stories of Irish priests, introduced by Harriet O’Donovan [later Harriet O’Donovan Sheehy], and published in America as A Set of Variations (1969); papers held at Mugar Library [of] Boston University, the University of Florida (Gainsville), and Univ. of Delaware (Special Collections), as well as in Harriet’s home in Dalkey; later acquired by Boole Library, UCC - incorporating the O’Connor papers of Ruth Sherry of Trondheim Univ., who bequeathed them on her death from cancer; a biography was issued by James H. Matthews (1983), and another by Jim McKeon (1998), the latter with Harriet’s endorsement; his birthplace was restored in 2012. NCBE DIB DIW DIL OCEL KUN FDA HAM OCIL WJM |

Frank O’Connor A Frank O’Connor Research Website can be found at University College, Cork, incorporating a New Digital Bibliography based on the 3,200-strong card-index compiled by the late Ruth Sherry (Trondheim Univ.) and acquired by the Boole Library as part of the O’Connor papers held by Harriet O’Donovan Sheehy in her Dalkey home - see online.

A Frank O’Connor Centenary Conference organised by Hilary Lennon was held on 12-14th September 2003 in the Máirtín Ó Cadhain Theatre of the Arts Building, Trinity College, Dublin. An opening address by Terence Brown on Friday night was followed by a programme of two-speaker panels covering the following topics: ‘O’Connor and the Abbey Theatre’ (Hilary Lennon, TCD; ‘Fierce Passions for Middle-Aged Men’: Frank O’Connor and Daniel Corkery’ (Paul Delaney, TCD); ‘O’Connor as Translator and Interpreter’ (Alan Titley, St. Patrick’s/DCU); ‘Frank O’Connor and John V. Kelleher’ (Charles Fanning, S. Ill. U); ‘O’Connor’s “Ghosts” and American Connections’ (Robert Evans, Auburn U); ‘ Frank O’Connor’s Autobiographical Writings’ (Ruth Sherry, NUST, Trondheim). See Lennon, ed., Critical Essays (2007), infra.

University of Delaware (Special Collections) holds five MS plays of Frank O’Connor, having been acquired in 1987 - viz., In the Train (9 Dec. 1959), play for radio [18 lvs.]; The Luceys (1962-63), play for radio [22 lvs.]; The Invincibles [1937; recte Oct. 1938], play for radio [carbon typescript; 96 lvs.]; Interior Voices (13 June 1962), play for radio [35 lvs.]; A. E. Coppard (9 Nov. 1948), radio broadcast [4 lvs.]. (See Emory University’s Irish Literature Portal - online online [espec. O’Connor page].

[ top ]

Works

See separate file [infra].

Criticism

|

| General studies |

|

| See also |

|

|

Bibliographical details

Hilary Lennon, ed., Frank O’Connor: Critical Essays (Dublin: Four Courts Press 2007), 240pp. CONTENTS: Brendan Kennelly, ‘Light dying’; [poem]; Nicholas Allen, ‘Frank O’Connor and critical memory’; Terence Brown, ‘Frank O’Connor and a vanishing Ireland’; Paul Delaney, ‘“Fierce passions for middle-aged men”: Frank O’Connor and Daniel Corkery’; Philip Edwards, ‘Frank O’Connor at Trinity; a reminiscence’; Robert C. Evans, ‘Frank O’Connor’s American reception: the first decade (1931-41)’; Maurice Harmon, ‘Frank O’Connor: reluctant realist’; John Kenny, ‘Inside out: a working theory of the Irish short story’; Declan Kiberd, ‘Merry men: the afterlife of the poem’; Hilary Lennon, ‘Frank O’Connor and the Abbey Theatre’; Harriet O’Donovan Sheehy, ‘Memories’; Emilie Pine, ‘A landscape of betrayal: Denis Johnston’s Guests of the Nation (1935)’; Ruth Sherry, ‘Frank O’Connor’s autobiographical writings’; Michael Steinman, ‘“A phase of history” in the house: Frank O’Connor’s “Lonely rock”’; Carol Taaffe, ‘Coloured balloons : Frank O’Connor on Irish modernism’; Alan Titley, ‘The interpretation of tradition’. [Papers of 3-day conference of 12-14 Sept. 2003.]

[ top ]

W. B. Yeats: Yeats described O’Connor as ‘doing for Ireland what Chekhov did for Russia’ (See short notice of An Only Child, rep. edn. Blackstaff 1994, in Times Literary Supplement, 22 May 1994, by BK [prob. Brendan Kennelly]).

Roger McHugh, ‘Frank O’Connor and the Irish Theatre’, Éire-Ireland, 4, 2 (Summer 1969), pp.52-63, writes of the articles O’Connor wrote for The Bell in which he ‘indicated some of the advantages of collaboration which he had gleaned from experience. One was that of being able to use the theatre as a practical workshop in which practitioners of several crafts can work together. The theatre of the Elizabethans, of Moilère and of the early Abbey period had known this kind of collaboration; and indeed the appointment of O’Connor and of Higgins (Ernest Blythe was nominated by the Government) now seems part of Yeats’s plan to restore it, for about the same time the services of Hugh Hunt and of the designer Tanya Moisiewitsch had been enlisted by him. [...] The other relevant advantage which O’Connor mentions is that of learning by practical experience the difference between the art of the storyteller which, [...] has become accommodated to the solitary reader, and the public art of drama, whose practitioners must have a sense of community and of communication, so that the play becomes a shared game, the playwright using to the full extent the unique sounding-board which an audience provides.’ (pp.52-53 in McHugh.)

Harriet O’Donovan, Introduction to Set of Variations (1969), writes: ‘Frank O’Connor the most important single element in any story was its design. It might be years between the moment of recognizing a theme and finding the one right shape for it - this was the hard, painful work - the writing he did in his head. But once he had the essential bony structure firmly in place he could begin to enjoy the story and to start “tinkering” with the detail. It was this “tinkering” which produced dozens of versions of the same story. The basic design never changed, but in each new version light would be thrown in a different way on a different place. Frank O’Connor did this kind of rewriting endlessly - he frequently continued it even after a story had been published. Though this confused and sometimes annoyed editors, reviewers, and bibliographers, the multiplicity of versions was never a problem to him. When there were enough stories to form a new collection he didn’t try to choose between the many extant versions of them - he simply sat down and prepared to rewrite every story he wanted in the book. / That particular rewriting was directed toward a definite aim, which was to give the book of stories a feeling of being a unity rather than a grab bag of miscellany. He believed that stories, if arranged in an ‘Ideal ambiances’ could strengthen and illuminate each other. This unity was only partly preconceived; he continued to create it as he went along. He never wrote a story specifically to fit into a gap in a book, nor did he change names or locations to give superficial unity. Rather it was as though the stories were bits of a mosaic which could be arranged harmoniously so that the pattern they made together reflected the light each cast separately. Ultimately this unity probably sprang from his basic conviction that the writer was not simply an observer: “I can’t write about something I don’t admire. It goes back to the old concept of the celebration: you celebrate the hero, an idea.” / This means, of course, that Frank O’Connor had very definite ideas about the contents and arrangement of each new book of stories. If he had lived, this might have been a different book. As it is, I have had to choose, not only which and how many stories to include, but also which of the many versions of each story to print. There was also the problem of that “ideal ambiance” and the comfort of the knowledge that even his own “ideal ambiance would be shattered by the time the book appears.” I do not doubt that I shall have to answer to the author for each of these decisions. But for the stories themselves no one need answer. They are pure Frank O’Connor.’

Denis Ireland records O’Connor’s comments on Theobald Wolfe Tone’s Autobiography and on the abilities of L. A. G. Strong as a story-teller (From an Irish Shore, 1939), p.144 [see Denis Ireland, supra].

Benedict Kiely: ‘O’Connor touched depth [...] without any of the creaking machinery or obvious attempts to be significant that makes much modern literature ludicrous.’ (q. source; quoted in H. Matthews, Frank O’Connor, 1976, p.90).

Maurice Wohlgelernter, Frank O’Connor: An Introduction (1977) - remarks on the story “Father and Son”: ‘What O’Connor attempts to stress, apparently, is that fathers and sons need not confront each other in anger and disdain, as is so often the case in Irish households ... Fathers need not be wolves, nor sons bleating lambs. If only they could learn that life begins with the word! But O’Connor certainly is not oblivious to the fact that, among Irish fathers and sons, such civility is rare. Somewhere, the word, spoken softly, clearly, sympathetically, is being lost. And it may not always be due entirely to the Irish fathers themselves. Like fathers everywhere, they expect, but rarely receive, some recognition and even appreciation for their efforts. Those very expectations may be a cause for some of their bitterness and brutality.’ (p.91; quoted in Hilary Lennon, Introduction to Frank O’Connor, on Frank O’Connor Research Website - online; accessed 12.07.2012.)

John Wilson Foster, ‘The Geography of Irish Fiction’, in The Irish Novel in Our Time, ed. Patrick Rafroidi & Maurice Harmon (Université de Lille 1975-76), pp.90-103; espec. pp.98-100, discussion of Dutch Interior: ‘To image the self locked in an eternally present past, O’Connor creates in Dutch Interior a sense of timelessness. To image the self simultaneously trapped in an escapable place, he creates a sense of placelessness. Cork is never specified as the novel’s setting since O’Connor want to capture a nation-wide provincialism that is both pre-Revolutionary nationalism that has failed and post-Revolutionary nationalism that has been perverted. This provincialism inhabits .... the countryside no less than the city.... an exploration of the Irish self and the hostile spaces it both creates ad is forced to inhabit.’ (p.99.)

[ top ]

Declan Kiberd:, ‘Story-Telling: The Gaelic Tradition’, in The Irish Short Story, ed. Terence Brown & Patrick Rafroidi (Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1979): ‘[...] Frank O’Connor has even gone so far as to assert that the short story marks ‘the first appearance in fiction of the Little Man’ (25). In the opening chapter of The Lonely Voice, O’Connor articulates his belief that the short story is characterised by its treatment of ‘Submerged population groups’ (The Lonely Voice, 1963, p.18), of those lonely people who live on the fringes of society because of spiritual emptiness or material deprivation. America is offered as an example of a society composed almost entirely of ‘submerged population groups’ in their respective ethnic ghettoes after immigration from Europe.’ (p.20.)

Declan Kiberd, review of David Marcus, ed., Faber Book of Best Irish Short Stories, in The Irish Times (3 April 2005, p.11): ‘The romance between Irish and American story-writers has long ago been consummated, and Richard Ford is but the most recent Yank to salute Frank O’Connor as one of his exemplars [...] Frank O’Connor, in due time, came up with a modification of this theory [i.e., Seán O’Faolain’s]. In The Lonely Voice he argued that the short story “marks the first appearance in fiction of the Little Man” and that it is characterised by its treatment of the “submerged population group”, those lonely persons who live on the fringes of society because of spiritual emptiness or material deprivation. No wonder that both he and Ó Faoláin saw the story as the appropriate form for the risen people, the rebels on the run, the Os and the Macs. [...]’ (Cont.)

Declan Kiberd (review of Marcus, ed., Faber Book of Best Irish Short Stories, 2005) - cont.: ‘Once upon a time, castigators of the form saw in it a sort of apprenticeship served by writers who might, if gifted, go on to compose full-blown novels. That seemed to be O’Faolain’s general position. But it was never O’Connor’s: he recognised that major novelists such as Trollope could sometimes write badly and get away with it, but that no great storyteller could be an inferior writer, because the true affinity of that genre was with the pure art of the lyric poem rather than the applied art of the novel. / That the “short story or novel?” debate was based on a false dichotomy is obvious now. The vast majority of Marcus’s contributors, from Colm Tóibín to Edna O’Brien, are recognised practitioners of the novel. It is notable, however, at most powerful contribution here once again written by Claire Keegan, who has yet to produce in the “applied” form.’ (For longer extract see under Kiberd, Quotations, supra.)

Terence Brown & Patrick Rafroidi, eds., The Irish Short Story (Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1979): Speaks of ‘O’Connor intuitive and discursive’ as distinct from O’Faolain’s intellectual and formal temper. Further: ‘O’Connor’s celebrated series of childhood stories deals with the friction between a child and adult institutions which he does not [55] fully comprehend and of which he becomes an unconscious infant parody. “My Oedipus Complex׆ [Stories of Frank O’Connor, 1965] for example sees the child defining his need for self-expression against the formal relationship of marriage, while in “The Drunkard׆ Larry acts in ironic mimesis of his father’s folly, and in “The Idealist׆ he escapes from the conformist pressures of school into an imaginative world in the invisible presence of first Etonian a “toffs׆ and later Western desperadoes. The ironies become deeper, almost Swiftian, when O’Connor is dealing with the destruction wrought by ideals elevated to the level of rigid orthodoxy in the “mature׆ world. In “Freedom׆ and “Guests of the Nation׆ he expresses shock and disgust at the denial of human qualities for the sake of an abstract principle. As he says in An Only Child - “I could be obstinate enough when it came to the killing of unarmed soldiers and girls because this was a basic violation of the imaginative concept of life׆ [An Only Child, Macmillan 1965, p.240.] / Like Shaw in John Bull’s Other Island , O’Connor shows himself in “The Ugly Duckling׆ to be aware of the destructive unreality of living too exclusively in the realm of imagination. Nevertheless, it seems safe in the light of the evidence both of his fiction and of his autobiographies to conclude that his turning finally from poetry to storytelling in “celebration of those who for me represented all I should ever know of God׆, is related to his own response to “the imaginative concept of life׆.

John Montague calls his Backward Look (1967) ‘among the very best of causeries on early Irish literature’, in ‘The Bag Apron: The Poet and his Community’, Fortnight (Jan. 1999), p.19.

Mary Campbell, review of An Only Child and My Father’s Son [Blackstaff reprints], in Books Ireland (Summer 1995), cites remarks, ‘An Irish writer without contention is a freak of nature; all the literature that matters to me was written by people who had to dodge the censor’ (1938); ‘warm, dim odorous, feckless evasive southern quality’ of Cork; ‘When the adventure of the community begins to dominate the imagination of the artist, he realises he must back away’ (on Republican involvement; ending of An Only Child); ‘cut off from ordinary intercourse in a way that seems unknown in other countries’ (on the artist in Ireland); devotion to Yeats; ‘After my father I never quarrelled so much with anyone ... one might say I was discovering my real father at last and all the old attitudes induced by my human father came on top’; death of Yeats resulted in rapid decline of Abbey, already effected by his failing spirit in old age; advent of Ernest Blythe; ‘this kind of infighting and intrigue was something I could not carry on alone ... Christmas pantomimes in Gaelic guying the ancient sagas ... One by one they lost their great actors and replace them with Irish speakers ... the members of the board with civil servants and lesser party politicians ...’; resigned from all public organisations and sat down to write. (Books Ireland, p.165.)

P. J. Kavanagh, ‘Bywords’ [visit to Dunfanaghy where the critic reads James Matthews, Voices], Times Literary Supplement (5 Dec. 1997), [q.p.]; quotes: ‘By 1947, he had antagonised just about everyone in Ireland, not only the pietists and the patriots, but the mainstream literati as well, Flann O’Brien, Austin Clarke, Anthony Cronin …’. Kavanagh credits O’Connor with having [exposed] Patrick Kavanagh to almost universal sneering (‘the lavatory poet’); quotes O’Connor in his address at Yeats’s grave in 1965, claiming that he had fought for ‘for an Ireland where people would disagree without recrimination and excommunication … stop turning everything we love, from our language to our religion, into a test of orthodoxy’ - which, acc. To P. J. Kavanagh, is precisely what he and others did; O’Connor disliked the epitaph on Yeats’s grave, and preferred a line from The Herne’s Egg: ‘that I / [a]ll foliage gone / Should shoot into my joy’; wrote instructions for his own grave: ‘Then take me to the Ulster Border, / And beg me a stone from the Orange Order. / A pillar of stone both tall and slender. / Frank O’Connor & “No Surrender!”’

Patricia Craig, review of Jim McKeon, Frank O’Connor: A Life (Edinburgh: Mainstream 1998), 192pp., in Times Literary Supplement (20 Nov. 1998), p.32: disparages the treatment of Gaelic literature as “drab and pedantic”; concludes, ‘… we are left without even a sense of any credo underlying O’Connor’s writing, or his personal life. Though he has tackled it with gusto, and with a disarming camaraderie for his subject, Jim McKeon has produced an abridged account of an eventful life - good-hearted, high-spirited and utterly unanalytical.’

[ top ]

Melissa Bostrom [University of N. Carolina, Chapel Hill], ‘Story into Short Story: Cultural Roots and Cultural Work’, in “The Work of Stories” [Fourth Media in Transition Conference, 6-08 May 2005 - MIT, Cambridge, Mass.): ‘Frank O’Connor, in his influential 1963 book The Lonely Voice, worked to distinguish the short story from what he characterized as the “wild improvisation” of storytelling. Instead, O’Connor insisted that the short story “began, and continues to function, as a private art intended to satisfy the standards of the individual, solitary, critical reader.” (The Lonely Voice: A Study of the Short Story, Cleveland: World Publishing Co., 1963, p.114.) His insistence on divorcing the literary genre from any connection to folk traditions seems to stem from an anxiety that emphasizing the story’s orality might only buttress the beliefs of a literary culture that prized the novel over the short story. For O’Connor, as for many critics of the short story, the relationship of the literary genre to the folk tale was pivotal in determining its cultural worth. Often seeing themselves as defenders of an underappreciated form, many short story critics interpreted the genre’s heritage - or lack thereof - in storytelling as key to determining its reception on the larger literary scene.’

See note 1: O’Connor also, however, repeatedly uses the term story-telling to describe the process of writing both short stories and novels, calling the former “pure storytelling” and the latter “applied storytelling” (p.27). It’s as if he can only link stories to storytelling if novels can be treated the same way, so that the connection to oral tradition itself is not used to denigrate the genre he champions. [See pdf abstracts, and this paper, online.]

Deborah Averill, ‘A Critical Essay on Frank O’Connor’, in Bookrags [pay-site]: ‘A reader of Frank O’Connor’s stories notices at once their atmosphere of warm intimacy. His concern with human contact originates in his sense of human isolation and it pervades his work; characters continuously touch each other, lie in bed discussing their problems or fall in love, and the narrative itself reflects a lively compassion which gives these stories their distinctive relevance. / His perceptions of emptiness lead him to seek an intensification of life. He delights in sheer animal vitality and encourages a full, waking life of the senses .... He dislikes abstractions, “the Greek reasoning about life which are our daily bread”, and thinks they have crippled modern literature as well as modern society by creating artificial barriers to communication. He tries to create an attitude of mind informed from within, from nature and the “inner light”, to overcome the literal application of sterile social mores, theories or religious ...’ (See Bookrags - online; associated with Amazon copy of The Best of Frank O’Connor, introduced by Julian Barnes (Everyman [2009]; accessed 12.07.2012.)

Alan Titley, ‘The Reshaping of Tradition: The Case of Frank O’Connor’, in Nailing Theses: Selected Essays (Belfast: Lagan Press 2011): ‘[...] I am not aware of any success or much interest in original poetry by O’Connor himself. / It is doubly curious because any translator of poetry must have a lively and sympathetic understanding of the society and of the people who produced it. I cannot argue that O’Connor didn’t have this, but he had a decidedly and sometimes even batty judgement of writers and works of literature is both his glory and his weakness. He can be at turns brilliantly insightful, searingly imaginative and then just plain wrong. But we are always aware of an intense and personal engagement with the literature. He shows no tiresome detachment, no two-handed objectivity and when he gets bored he just tells us straight up. The result is to draw us into the debate, and when we disagree with him as I do again and again with equal vehemence, we feel that he would thoroughly enjoy a robust altercation about the nature of Irish of literature and the possibilities of translation.’ (p.102; cont.)

Alan Titley, ‘The Reshaping of Tradition: The Case of Frank O’Connor’, in Nailing Theses (2011) - cont.: In The Backward Look, for example, he has a wonderful way with generalisations. “The Irish had the choice between imagination and intellect,” he declares, “and they chose imagination.” (The Backward Look [BL], 1967, p.1.) Matthew Arnold and Lord Macauley and purveyors of the myth of the helpless, hapless Celt would agree. Unlike Daniel corkery, who wrote a very lyrical and wrong-headed book on it, I see nothing to admire in Irish 18th-century poetry.” (BL, p.114.) This is an awful lot of poetry, and poets, and matters, and genres not to admire. “Of twelfth-century Irish literature he says, “It has no real prose, and consequently no intellectual content.” (BL, 86.) This will be grating music to the ears of our thousands of poets. Over more than a thousand years he refers to “the Irish type of mind, which is largely the mind of primitive man everywhere”. (BL, p.11.) This could be construed as being an insult to the Irish or more seriously to those primitive wheresoever they might dwell.’ [Cont.]

Alan Titley, ‘The Reshaping of Tradition: The Case of Frank O’Connor’, in Nailing Theses (2011) - cont.: As against that his critical comments which depend on taste and judgement are often brave and incisive. He does argue tha”t scholars who are also men of letters should trust their instincts” (BL, p.33) and we suspect he might be referring to himself. His opinion of the Táin or “Cattle Raid of Cooley” as “a simply appalling text” and “a rambling tedious account” of a long-forgotten war strikes chords in honest readers. (BL, p.33.) He captures the mood of what most aristocratic poets must have felt when poetry deteriorated from syllabic to accentual in the 17th [104] century: “Every peasant poet was hammering it out with hobnailed boots like an ignorant audience listening to a Mozart minuet. It is no wonder if it offended O’Hussey’s delicate ear; it often offends mine.” (BL, p.107.) We know that O’Connor despised the poetry of vassals and churls composed in the misery of their hutments. And his assertion that the golden era of early Irish literature “ended with what might be called the Cistercian invasion, which in intellectual matters was direr than the Norman invasion” may see like the sweep of anotehr totalising impulse, but it does have pith and substance. (BL, p.256.) / These whanging declarations make us sit up and take note. The exaggerating posture usually contains a big truth. [...]’ (pp.104-05.)

Note: Titley suggests that Irish ‘culturists’ have ‘a vested interest in the primitive, the pagan, the folk’ [.. &c.] and others ‘wish to see the Irish world as utterly cosmopolitan, ultimately derivative, a part of the main’ and that ‘O’Connor veered between these depending on when he wrote and who was the enemy.’ (p.116). He concludes by saying: ‘His assertion that “the only significant element is English” in the Irish literature of the 18th century is pure tosh. (BL, p.109.)’

[ top ]

Quotations| Individual Texts | Sundry Remarks |

| Prose: Individual texts | |

|

“Guest of the Nation” (1930) |

“Future of Irish Literature” (1942) |

| Modern Irish Short Stories (1957) The Lonely Voice (1963) |

An Only Child (1961) |

| full-text copys of the criticism of Frank O’Connor* | ||||

|

| Poetry: Translations from the Irish |

| Translation of Buile Suibne (Gaelic Poetry) |

[ top ]

Prose

“Guest of the Nation” (Atlantic Monthly, 1930): ‘By this time we’d reached the bog, and I was so sick I couldn’t even answer him. We walked along the edge of it in the darkness, and every now and then Hawkins would call a halt and begin all over again, as if he was wound up, about our being chums, and I knew that nothing but the sight of the grave would convince him that we had to do it. And all the time I was hoping that something would happen; that they’d run for it or that Noble would take over the responsibility from me.’ (Rep. in William Trevor, ed., Oxford Book of Irish Short Stories, 1989, p.353; quoted in Rosemary McGookin, UG Essay, UUC 2007.)

“Guest of the Nation” [ending]: ‘[...] but with me it was as if the patch of bog where the Englishmen were was a million miles away, and even Noble and the old woman, mumbling behind me, and the birds and the bloody stars were all far away, and I was somehow very small and very lost and lonely like a child astray in the snow. And anything that happened to me afterwards I never felt the same about again’ [End.] (Collection Two, 1964, p.12; Trevor, op. cit., p.353.)

‘The Future of Irish Literature’, in Horizon (ed. Cyril Connolly; 5, 25 Jan. 1942): ‘Irish literature, as I understand it, began with Yeats and Synge and Lady Gregory; it has continued with variations of subject and talent through a second [500] generation. Is there to be a third, or will that sort of writing be re-absorbed into the mainstream of English letters?’ (q.p.; rep. in David Pierce, ed., Irish Writing in the Twentieth Century: A Reader, Cork UP 2000, p.500-01.)

‘The Future of Irish Literature’ (1942): ‘In those days there were at least half a dozen movements to which any young man of spirit could belong; all of them part of a general attack my the younger generation on the enemies within: the imitator of English ways - the provincialist; the “gombeen man” - a very expressive Irishism for the petit bourgeois; and the Tammany politician who had riddled every institution with corruption. Irish literature fitted admirably into that idealistic framework; it wa another force making for national dignity.’ (p.56.)

‘The Future of Irish Literature’ (1942) - further: ‘Irish society began to revert to type. All the forces that had made for national dignity, that had united Catholic and Protestant, aristocrats like Constance Markiewicz, laour revolutionoists like Connolly and writers like “AE” [Æ], began to disintegrate rapidly, and Ireland became more than ever sectarian, utilitarian (the two nearly always go together) vulgar and provincial.’ (idem.; rep. in David Pierce, ed., Irish Writing in the Twentieth Century: A Reader, Cork UP 2000, p.500; quoted in Carl Campbell, MA Diss., UUC 2009.)

‘The Future of Irish Literature’ (1942) - further: ‘a vicious and ignorant middle-class, and for aristocracy the remnants of an English garrison, alien in religion and education. From such material he finds it almost impossible to create a picture of life which, to quote Dumas’[s] definition of the theatre, will embody “a portrait, a judgement and an ideal”’ ( Horizon, Jan. 1942., p.61; quoted in Terence Brown, ‘After the Revival: The Problem of Adequacy and Genre’, in The Genres of Irish Literary Revival, ed. Ronald Schleifer Oklahoma: Pilgrim; Dublin: Wolfhound 1980, pp.153-78; p.158.)

‘The Future of Irish Literature’ (1942) - further, gives an account of the significance of W. B. Yeats’s passing, called ‘unforgettable’, with a quotation on Yeats’s character as a ‘rabid Tory’. (Cited in Roy Foster, ‘When the Newspapers Have Forgotten Me ...’, in Yeats Annual 12, 1996; see further under W. B. Yeats, infra.]

‘The Future of Irish Literature’ (1942) - further: ‘Ireland has used her new freedom to tie herself up into a sort of moral Chinese puzzle from which it seems impossible that she sould ever extricate herself [...] Every year that has passed, particularly since de Valera’s rise to power, has strengthened the grip of the gombeen man, of the religious secret societies like the Knights of Columbanus [and] the illiterate censorships.’ (Rep. in David Pierce, ed., Irish Writing in the Twentieth Century: A Reader, Cork UP 2000, p.500; quoted in Carl Campbell, MA Diss., UUC 2009.) [For full text, see in RICORSO Library, “Irish Critical Classics”, infra.)

Modern Irish Short Stories (1957; reiss. as Classic Irish Short Stories, 1985): ‘I believe that the Irish short story is a distinct art form: that is, by shedding the limitations of its popular origin it has become susceptible to development in the same way as German song, and in its attitudes it can be distinguished from Russian and American stories which have developed in the same way. The English novel, for instance, is very obviously an art form while the English short story is not.’ [ix; ...]

Modern Irish Short Stories (1957; reiss. 1985) - cont.: ‘I have preferred to keep to my own idea of the short story as an art form distinct from the tale, though I realise that the distinction may be more philosophical than critical. As I understand it, the short story derives from the novel, and like the novel has attempted successfully to combine artistic and scientific truth. The latter is not an artistic standard - critics who disapprove of it are right in this - but it is its application to artistic ends that has made fiction the greatest of the modern arts.’ [xv]. (Includes remarks on numerous Irish writers; for full text, see “Irish Classics”, infra.)

[ top ]

| The Lonely Voice: A Study of the Short Story (London: Macmillan 1963) - extracts: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| [ top ] |

An Only Child (1961) ‘I hated every member of my father’s family - even cousins I later grew fond of. It was not the people themselves I hated of course, but drunkenness, dirt, and violence.’ (p.20.) Further: ‘Whenever he [his father] brandished the razor at mother, I went into hysterics, and a couple of times I threw myself on him, beating him with my fists. That drove her into hysterics too, because she knew that at times like that he would as soon have slashed me as her.’ (p.35; quoted in Carl Campbell, UUC MA Diss., 2009.)

An Only Child (1961)- on being asked to shoot Free-State soldiers courting girls in Cork: ‘It was clear to me that we were all going mad, and yet I could see no way out. The imagination seems to paralyse not only the critical faculties but the ability to act upon the most ordinary instinct of self-preservation. I could be obstinate enough when it came to killing unarmed soldiers and girls because it was a basic violation of the imaginative concept of life, whether of boys’ weeklies or the Irish sagas, but I could not detach myself from the political attitudes that gave rise to it. I was too completely identified with them, and to have abandoned them would have meant abandoning faith in myself.’ (An Only Child, 1961, p.168; quoted in Peter Costello, The Heart Grown Brutal: the Irish Revolution in Literature from Parnell to the Death of Yeats, 1891-1939, Gill & Macmillan 1977, p.217.)

An Only Child (1961) - on post-Independence Ireland: ‘What neither group saw was that every word we said, every act we committed, was a destruction of the improvisation and what we were bringing about was a new establishment of Church and State in which imagination would play no part, and young men and women would emigrate to the ends of the earth, not because the country was poor, but because it was mediocre.’ (An Only Child, Macmillan [1961] 1965, p.210; quoted in David Norris, ‘Imaginative Response versus Authority Structures: A Theme of the Anglo-Irish Short Story’, The Irish Short Story, ed. Terence Brown & Patrick Rafroidi, Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1979, p.41.) [See same in 1961 edn. at pp.243-44.]

An Only Child (1961): ‘This was all our romanticism came to - a miserable attempt to burn a widow’s house, the rifle butts and bayonets of hysterical soldiers, a poor woman of the lanes kneeling in some city church appealing to a God who could not listen, and then - a barrack wall with some smart humbug of a priest muttering prayers ... certainly that night changed something in me forever.’ (pp.243-44; quoted in Carl Campbell, MA Diss. UUC 2009.)

An Only Child (1961) - Sundry remarks on early days: ‘I saw life through a veil of literature.’ (p.44); ‘I took the republican side because it was Corkery’s.’ (p.211.)

An Only Child (1961): ‘All I could believe in was words, and I clung to them frantically. I would read some word like “unsophisticated” and at once I would want to know what the Irish equivalent was. In those days I didn’t even ask to be a writer; a much simpler form of transmutation would have satisfied me. All I wanted was to translate, to feel the unfamiliar become familiar, the familiar take on all the mystery of some dark foreign face I had just glimpsed on the quays.’ (An Only Child, p.170; quoted in Helen Lojek, ‘Brian Friel’s Plays and George Steiner’s Linguistics: Translating the Irish’, in Contemporary Literature, Spring 1994, p.96.)

An Only Child (1961), Chap. 15 [concerning the schoolteacher Denis Breen]: ‘I did not like Breen. His mother told my mother that even when he was a small boy no one could control him [...] He was greedy with a child’s greed, shouted everyone down with what he thought were funny stories or denunciations of the “bleddy eejits” who ran the country or its music, and battered a Beethoven sonata to death with his red eyebrows reverently raised, believing himself to be a man of perfect manners, liberal ideas, and perfect taste. [...] He quarrelled bitterly with me after the first performance of a play called The Invincibles [by Thomas Morton, 1829] because he had convinced himself that I had caricatured him in the part of Joe Brady, the leader of the assassins - a brave and simple man driven mad by injustice - and though at the time I was disturbed because such an idea had never occurred to me, it seems to me now that the characters in whom we thing we recognise ourselves are infinitely more revealing of our real personalities than those in which someone actually attempts to portray us.’ ( pp.192-93; rep. in The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing, gen. ed. Seamus Deane, Derry: Field Day 1991, Vol. 3.)

[ top ]

[ top ]

| Sundry remarks | ||

| Anglo-Irish literature Irish literature Irish short story |

Irish anger Gender politics The later Abbey |

Doran’s ass Dublin’s Fair city A Joycean touch? |

Anglo-Irish literature: ‘The first great masterpiece of literature written in English in this country is A Modest Proposal, and I would ask you to remember that it is a political tract. That political note, I would suggest, is characteristic of all Anglo-Irish literature. I know no other literature so closely linked to the immediate reality of politics.’ (The Backward Look, 1967, p.121; quoted in Heinz Kosok, ‘The Easter Rising versus the Battle of the Somme: Irish Plays about the First World War as Documents of the Post-colonial Condition’, in Munira H. Mutran & Laura P. Z. Izarra, eds., Irish Studies in Brazil, Associação Editorial Humanitas 2005, p.89.)

[Note: Quotations from The Backward Look are widely distributed through RICORSO -see for instance, under Charlotte Brooke, “Commentary”, infra.]

Irish literature in Irish: ‘Irish literature in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was dying in its sleep. It was linked to a semi-feudal artistocracy and could either disappear with it or linger on with that small element of aristocracy that remained, and was gradually, by denial of education and advancement, being forced down into the ranks of peasantry, themselves condemned to an existence resembling that of Russian serfs or Negro slaves.’ (In The Backward Look: A Survey of Irish Literature, Northumberland Press 1967, p.111.)

Irish short story: ‘We all came out from under Gogol’s “Overcoat׆.’ (Quoted in Sophia Hillen King, ‘The Millstone and the Star, Regionalism as Strength’, in Linen Hall Review, Autumn 1994, p.8.) [Note that Dostoeyevski said that that modern literature came out of the pocket of Gogol’s comic-grotesque masterpiece The Overcoat (1842).]

‘“Is this a dagger?”’, in Nation, No. 186 (1958): ‘None of us could ever fashion a story or a play into a stiletto to run into the vitals of some pompous ass. Oliver Gogarty, like Brian O’Nolan of our time, could make phrases that delight everybody, but the phrases never concentrated themselves into the shape of a dagger; they were more like fireworks that spluttered and jumped all over the place, as much a danger to his friends as to his enemies. Irish anger is unfocused; malice for its own sweet sake, as in the days of the bards.’ (p.170; quoted in Michael Patrick Gillespie, ‘She was too Scrupulous Always: Edna O’Brien and the Comic Tradition’, in The Comic Tradition in Irish Women Writers, ed. Theresa O’Connor (Florida UP 1996, p.109; citing Vivian Mercier, The Irish Comic Tradition, OUP 1962, p.182.)

Gender politics: ‘Men have written the literature of Irish renaissance because politics is the stuff of literature.’ (Frank O’Connor, 1963; cited in Ann Owen Weeks, Irish Women Writers: An Uncharted Tradition, Kentucky UP 1990, p.9.) Further, Further, ‘ [...] the literature of the Irish literary Renaissance is a peculiarly masculine affair ... it is in society that women belong.’ (Epigraph to Wilson, & Somerville-Arjat, [interviews] eds., Sleeping with Monsters, Dublin: Wolfhound 1990.)

The later Abbey: ‘The most famous building in Dublin is the architecturally undistinguished Abbey Theatre, once the city morgue and now entirely restored to its original purposes.’ (From Leinster, Munster, and Connaught; cited in P. J. Kavanagh, Voices in Ireland, 1994, p.288.)

Doran’s ass: O’Connor once summed himself up as ‘a natural collaborationist [...] Like Doran’s ass, I go a bit of the way with everybody.’ (See short notice of An Only Child, rep. edn. Blackstaff 1994, in Times Literary Supplement, 22 May 1994, by BK [prob. Brendan Kennelly]).

Fair city? O’Connor wrote that Dublin was [in 1904] ‘a glorified market town where droves of cattle [could] still be seen in the streets and which [was] populated by an imperfectly urbanised peasantry’. (O’Connor, ‘James Joyce’, in The American Scholar, 36, Summer 1967, pp.466-90; cited in James Fairhall, James Joyce and the Question of History, Cambridge UP 1993).

Achill & Aran: ‘People who come to Ireland on holiday are advised to go either to Achill or to the Aran Islands. Maybe they are well advised; they seem to get over it quite well and have even been known to return. I suppose it depends on the sort of thing you’re used to.’ (Leinster, Munster and Connaught, 1950, q.p.; quoted in Rick LeVert, review of exhibition of Ciaran McNally’s travel collection [University of Limerick], in The Irish Times, 21 Feb. 2009, Weekend Review, p.8.)

Joycean touch?: ‘An Irishman’s private life begins at Holyhead’ (Q. source].

[ top ]

References

Henry Boylan, Dictionary of Irish Biography (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1988) remarks that his Golden Treasury (1967) covers the ‘most important branch of medieval poetry [...] from the only period when Ireland was an independent country’.

Website: There is a Frank O’Connor Research Website at University College, Cork - online.

Seamus Deane, gen.ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 2, selects ‘Guests of the Nation’. Vol. 3 selects ‘The Majesty of the Law’ from Bones of Contention; also extract from An Only Child (1961) [pp.469-80]; BIOG incl. rems.: ‘O’Connor’s outspoken criticism of social and moral hypocrisy in Ireland and his own tempestuous personal life made his position difficult in Ireland and in 1951 he left for a teaching post in the United States, where he spent much of the rest of his life.’ Bibl., The Backward Look published in American as A Short History of Irish Literature (NY: Putnam 1967). Further remarks at pp.92-93, 247, 383, 481, 937, 939-41, 1133, 1312, 1353-54.

Helena Sheehan, Irish Television Drama, A Society and Its Stories (RTE 1987), lists RTÉ films, Guests of the Nation (1969), adpt. by James Douglas, dir. Brian Mac Lochlainn [113, 114], In the Train (1963), dir. Jim Fitzgerald (1963); Orpheus and His Lute (1969), adapt. John McDonnell, dir. Brian Mac Lochlainn.

Kevin Rockett, et al., eds., Cinema & Ireland (1988), lists Guests of the Nation, 60-2 [1935; 50 min. film dir. Denis Johnston, made during summers of 1934-35; shows influence of Eistenstein’s montage; Mary Manning worked on the script; her brother John on camera; Barry Fitzgerald, Shelah Richards, Denis O’Dea, Hilton Edwards, Fred Johnson and Cusack, actors], 121.

Hyland Books (Cat. 214), lists Fountain of Magic (1939), with pref. acknowledgement that Yeats ‘worked over some of the poems; one or two he has made into new poems’ [but those poems not identified in Wade]; The Road to Stratford (1948); Towards an Appreciation of Literature (1945); The Art of the Theatre (1947), 50pp.; Traveller’s Samples, Stories and Tales (1951), The Stories of Frank O’Connor (1st ed. 1953); An Only Child (1st ed. 1961); Preface to Nigel Heseltine trans. of Dafuydd Ap Gwilym, Selected Poems (Cuala Press 1944) [280 copies].

[ top ]

Notes

Looking back: The title of O’Connor’s literary history of Ireland, published as The Backward Look: A Survey of Irish Literature (London: Macmillan 1967), echoes Sir Samuel Ferguson’s idea of ‘living back in the country we live in’. The work is dedicated to the author’s children [sic]: ‘Look back to look forward’. (Cited in Patrick Rafroidi, Irish Literature in English, The Romantic Period, Vol. 1, 1980, p.149).

Note that the phrase ‘backward glance’ is also employed by Seán O’Faoláin in ‘The Social Reality’ [chap.], The Irish (1947): ‘In modern Eire a good deal of lip-service is paid to the family-unit. If there is, in this, any backward glance at the old Celtic system it is wholly sentimental. In practice we owe all the legal rights and restrictions that we enjoy and accept to the ‘brutal’ Normans and the ‘brutal’ Tudors who are supposed to be responsible for the ‘seven hundred years of slavery’ about which our patriots glibly talk without knowing anything much about it. If Celtic tradition has given us anything in this field it has given us atavistic individualism [...].’ (p.41; my italics.) Finally, the phrase is prominently used in Seamus Deane, Short History of Irish Literature (London: Hutchinson: 1986).

Irish language: O’Connor records that his teacher Daniel Corkery one day wrote something on the blackboard in a strange language - Muscail do mhisneach, a Bhanba [awaken your courage, Ireland] - after which O’Connor discovered that his grandmother knew that language. (Supplied by Maurice Harmon.)

Genealogy: children of Michael O’Donovan: m. Evelyn Bowen, 11 Feb. 1939; son Myles O’Connor, b. 18 July 1939; dg. Liadain O’Connor, b. 27 Nov. 1940; Joan Knape gives birth to their son Oliver, June 1945; Evelyn gives birth to Owen O’Connor, June 1946; m. Harriet Rich, 5 Dec. 1953; dg. Hallie-Og, b. 25 June 1958.

Biographers: The biography of O’Connor by Jim McKeon, a Corkman, drawing on papers made available by O’Connor’s widow Harriet O’Donovan Sheehy [May 1996]; Jim Matthews, author of the Bucknell UP biography, is also Cork-born.

The Invincibles: O’Connor’s play of this title is based on the ‘Phoenix Park Murders’ perpetrated in Dublin on 6 May 1882 by members of the Irish National Invincibles, a Fenian splinter group. (For further details of the Invincibles, see under Charles Stewart Parnell - infra.)

See Ruth Sherry, ed., Hugh Hunt, The Invincibles (Newark: Proscenium 1980) - and details at Irishplayography - online. Original cast of production on 18 Oct. 1938 there given as follows: Inspector Mallon - Cecil Barror; P.J. Tynan - Frank Carney; Timothy Kelly - Cyril Cusack; Ned McCaffrey - Laurence Elyan; Daniel Curley - Eric Gorman; Mrs. Brady - Christine Hayden; James Carey - Fred Johnson; Joe Brady - W. O’Gorman; Mr. O’Leary - W. Redmond; Maggie Fitzsimons - Sheila Ward. Production by Hugh Hunt.

Sylvia Plath applied for Frank O’Connor’s Harvard Summer School in 1953 and attempted suicide by sleeping pills on being turned down.

Nancy McCarthy: a postcard to McCarthy which was originally laid in an uncorrected proof copy of O’Connor’s Guests of the Nation is held in the University of Delaware Library (Special Collections, PR6029.D58 G8x, 1931).

O’Connor Prize: The Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award was presented to Haruki Murakami at the Cork Arts Festival in Sept. 2006.