Oscar Wilde: References & Notes

| References | Notes |

|

|||

|

|||

References

John Sutherland, Oxford Companion to Victorian Fiction, give bio-dates, 1854-1900 [sic]; separate entry for The Picture of Dorian Grey, serialised in abbrev. form in Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine, 1890. The mawkish “Ballad of Reading Gaol” appeared in 1898; Wilde’s disgrace and persecution had an enduring effect

on English literary culture whose tentative flirtations with decadence, aestheticism and post-Romanticism were promptly discontinued. BL 4 [fiction].

Internet resources ...

| Rachel Sahlman, Short Biography of Wilde |

|

||

| The Oscar Wilde Collection [stories, poems, fiction, plays] |

|

||

| “The Fisherman and his Soul” |

|

||

| *last available at 05.12.2009 | |||

[ top ]

Lord Alfred Douglas, ed., Plain English, Nos. 8-30, 30 Aug. 1920-29 Jan. 1921 [bound as 25 issues, some missing; rare periodical, edited and partly written by Douglas and showing him at his most crazily xenophobic; throughout are virulent attacks on the Jews, the Irish, Robert Ross, &c.; Douglas edited it for 16 moths, till mid 1921. Eric Stevens 1992 [Cat. 168] £145. Also Plain Speech, vol. 1 nos. 1-12., Oct. 1921-Jan 1922; identical in style and format to the previous, £55. Rupert Croft-Cooke, Bosie, The Story of Lord Alfred Douglas, his friends and enemies (London: W. H. Allen 1963), 414pp [1st], £12; Brian Roberts, Lord Alfred Douglas, The Mad Bad Line, the family of Lord Alfred Douglas (Hamish Hamilton 1981), 319, 8 plates [1st], £10.

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry 1991), Vol 2 selects The Happy Prince; Mr Froude’s Blue Book (on Ireland) [Viz., Two Chiefs of Dunboye, reviewed]; The Picture of Dorian Gray; Intentions, The Decay of Lying [from Intentions; and cf. Mahaffy, Decay of the Art of Preaching ]; The Importance of Being Earnest [376-91]; ‘The Ballad of Reading Gaol’ [731-37]; The Poems of Oscar Wilde, ‘Requiescat’ [elegy to his sister Isola], ‘Les Silhouettes’, ‘La Fuite de La Lune’, ‘The Harlot’s House’ [738-39]; BIOG 514 [and note misquotation of Lord Queensberry’s note]; References & Remarks: 8, 295, 372-76; Yeats met Wilde and others at the London home of W. E. Henley [Heaney, ed.], 787; [biog. Yeats, 830] [W. J. McCormack, Gothic connections, 837, 838, Stoker’s wife Florence Balcombe had been courted by Wilde, 1842; published version of Vera includes a crude anticipation of Lady Gregory’s Kiltartanese, 845; in addition to family’s devotion to things Irish, Lady Wilde had contributed to the store of Irish gothic writing with German translations [unspec., WJM], 846, [err. 848], [err. 859], 963n, [Frederick Ryan 999n], [Corkery, 1008]. Bibl. of works and criticism [as listed on this website - see Works, supra & Criticism, supra].

Jacqueline Wesley (Cat. 22; Oct. 1993) lists Arthur Ransome, Oscar Wilde: A Critical Study (London: Martin Secker 1912), 213pp., front. port [oil by Harper Pennington]; subject of a libel action brought by Lord Alfred Douglas because Ransome had described De Profundis as written to ‘a man to whom Wilde felt that he owed some at least of the public circumstances of his disgrace’; verdict given in favour of Ransome but passages complained of omitted from later editions; John Moray Stuart-Young, Osrac: The Self-Sufficient, and Other Poems, with a Memoir of the Late Oscar Wilde (London: Hermes Press 1905), 119pp. front. port., 5pls. and 2 facs. [contains 2 alleged facs. letters of Wilde to the author which are forgeries - as is the inscription on the portrait to “Johnnie” [Mason 681]; Sherard, Oscar Wilde Twice Defended from André Gide’s Wicked Lies and Frank Harris’s Cruel Libels to which is added A Reply to George Bernard Shaw / A Refutation of Dr. G. J. Renier’s Statements / A Letter to the Author from Lord Alfred Douglas, an Interview with Bernard Shaw by Hugh Kingsmill (Chicago: Argus Book Shop 1934), 76pp. [Note that a copy of the last held in the British Library was formerly owned by Lord Alfred Douglas and the whole formerly published by Vindex in Calvi, France. See COPAC online; accessed 27.02.2010.]

[ top ]

Libraries & Booksellers

Belfast Central Library holds Complete Shorter Fiction of Oscar Wilde, ed. Isobel Murray (OUP 1979); Wilde, Oscar, Aforismi, scelti e tradotti de Alex R Falzon (Milan: Epoca 1986), 155pp.; The Ballad of Reading Gaol, by C.3.3. (London: Leonard Smithers 1898), 31pp.; The Canterville Ghost (London: John W Luce 1906), 124pp.; A critic of Pall Mall, being extracts from reviews and miscellanies (London: Methuen 1919), 218pp.; De Profundis, 31st ed. (London: Methuen 1915), 156pp; 42 ed. (1927), 151pp. Among numerous other works not copied here are, The Fireworks of Oscar Wilde, selected and ed. and intro. Owen Dudley Edwards (London: Barrie & Jenkins 1959), 282pp.; Wilde, The Importance of Being Earnest and related writings (London: Routledge 1992), 271pp.; Importance, etc., drawings by Sheila Jackson (London: Grey Walls Press 1948), 86pp., col. ills.

Eric Stevens (Cat. 1992) lists H. Montgomery Hyde, The Other Love, an historical and contemporary survey of homosexuality in Britain (London: Heinemann 1970) [1st ed.], 323pp. [contains much about Wilde and Alfred Douglas, Eric Stevens 1992 £10; Also Wilde, Children in Prison & Other Cruelties of Prison Life (Murdoch & Co. 1898) [Long letter written by Wilde to the editor of the Daily Chronicle in defence of warder Martin who had befriended him during his last months in Reading and who had been dismissed as a result of his humane actions] [1st ed.], 16pp [rare], £135; ALSO Four Letters by Oscar Wilde [not included in the English ed. of De Profundis] (priv. 1906; 500 copies) [1st ed.], 34pp., £95; Lady Windermere’s Fan (Leipzig Tauchnitz ca.1933), 238pp., £3; Rupert Hart-Davis, The Letters of Oscar Wilde (London: Hart-Davis 1962) [1st ed.] xxv+958pp, 35 ills, £35; Hart-Davis, ed., More Letters of Oscar Wilde (London: Murray 1986; rep. of 1985), 215pp., £6; E. H. W. Meyerstein, Letter to RN Green-Armitage, 1940, 3pp. 4to, £25; François Porche, L’Amour Qui N’Ose Pas Dire Son Nom, Oscar Wilde (Paris: Bernard Grasset 1927) [9th ed.-] 242pp., £12; Kerry Powell, Oscar Wilde and the Theatre of the 1890s (OUP 1990) [1st ed.] 204pp., £15.

Oxford University Press (Cat. 1996) lists Isobel Murray, ed., Oscar Wilde, [Works], incl. The Picture of Dorian Gray; Lady Windermere’s Fan, The Importance of Being Earnest ; The Decay of Lying ; and The Ballad of Reading Gaol, with notes; 660pp.; also, Murray, ed., The Picture of Dorian Gray [World’s Classics] (OUP q.d.); Rupert Hart-Davis, ed., Selected Letters of Oscar Wilde (OUP [1962]), 432pp.; Rupert Hart-Davis, ed., More Letters of Oscar Wilde (London: John Murray 1985), 224pp.; Philip E. Smith and Michael S. Helfand, eds., Oscar Wilde’s Notebooks: A Portrait of Mind in the Making (OUP q.d.), 176pp., ill.; Murray, ed., The Soul of Man and Prison Writings [World’s Classics] (OUP q.d.), 248pp.

James Joyce held in his Trieste library copies of An Ideal Husband (Leipzig: Tauchnitz 1908); Intentions (Leipzig: English Library 1907); Lady Windermere’s Fan (Leipzig: Tauchnitz 1909), signed S. Joyce; The Picture of Dorian Gray (Leipzig: Tauchnitz 1908); Salomé(Leipzig: Tauchnitz 1909); Selected Poems (London: Methuen 1911); The Soul of Man Under Socialism (London: priv. 1904); A Woman of No Importance (Leipzig: Tauchnitz 1909); and R. H. Sherard, Oscar Wilde (London: Greening 1908). [See Richard Ellmann, The Consciousness of James Joyce, Faber, Appendix, p.133.]

Peter Harrington Books (Cat. 2005) lists The Picture of Dorian Gray (London: Ward, Lock & Co. 1891), 1st Edn., trad. iss., bound by Chelsea Bindery in full green morocco [£1,750].

[ top ]

Notes| References | Notes |

[ top ]

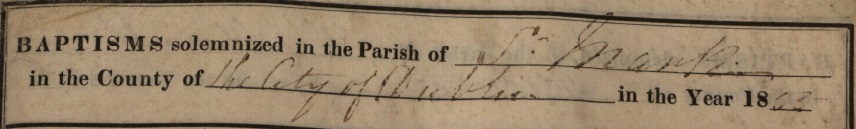

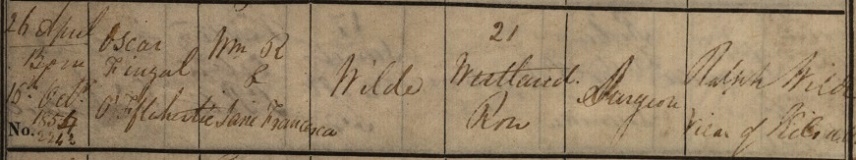

| Wilde’s Baptism dates as registered at the Parish Church of St Mark’s in Brunswick St., Dublin [now Pearse St, Dublin 2]. |

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

| Imagines extracted from the Church Records - online; view the full sheet here - as pdf; accessed 03.09.2020. | ||||

[ top ]

Vera, or the Nihilist (written 1880), combines details from the lives of Vera Figner, author of memoirs, who spent 22 years in Schlusselberg Fortress for her activities as an anarchist, and Vera Zasulich, who shot and wounded Gen. Trepov, City Prefect of St Petersburg, and went on to advocate the assassination of the Tsar; Wilde intended Sarah Bernhardt [recte Mrs. Bernard Beere] to play the part; in 1882, Bernhardt was playing in Fedora by Sardou, with a similar theme. (Q. source; corrig. supplied by D. C. Rose, Goldsmiths Coll., London, 27 July 2001.)

The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891) [I] - Plot: Dorian cruelly jilts Sybil Vane who then commits suicide. Gray decides to overcome his momentary guilt by viewing Sybil’s suicide as an artistic event, ‘It seems to me to be simply like a wonderful ending to a wonderful play.’ He is encouraged in this erasure by his Mephistopheles, Lord Henry Wotton, ‘The girl never really lived, and so she has never really died.’ Wilde’s book can be read as a protest against such deadly constructions of experience. Dorian’s wit runs to: ‘Men marry because they are tired; women, because they are curious; both are disappointed’.

Dorian Gray (1891) [II]: Dorian Gray, based on motif of the painting that drains the subject, developed by Poe in ‘The Oval Portrait’, and featuring Lord Henry Wotton (prob. based on the Elizabethan diplomat Sir Henry Wotton, ‘comforter of all youths’ in Izaak Walton’s phrase, who served as a diplomat between the court of the Duke of Florence and James VI of Scotland, afterwards James I of England); also includes thematic reference to the myth of Ossian, grandson of Fingal, who visits Tir na nOg; note that in Ancient Legends, Lady Wilde wrote a tale of ‘Oscar the Lion’, who cuts off the head of a treacherous Celtic chief, carry it back bleeding to the fort, where the blood releases the captive Fenian knights; Dorian’s mother ‘was a Devereux’ (i.e., of the stock of the ill-fated Earl of Essex). Dorian Gray was first serialised in Lippincott’s [July 1890].

Dorian Gray - English gent.? Though not himself aristocratic (”Mr Dorian Gray does not belong to the Blue-books” - Picture, Penguin Edn. 1994, p.41), Dorin was brought up by his aristocratic grandfather, the last lord of Kelso. (See Andrea Hermes, ‘Dorian Gray: Rebel or Sinner?’ - a seminar paper at Google Books [online].)

Dorian Gray (1891) [III]: Wilde defended Dorian Gray in letters to St. James Gazette (25 June 1890): ‘[T]he sphere of art and the sphere of ethics are absolutely distinct and separate’; and further, ‘good people, belonging as they do to the normal, and so commonplace, type, are artistically uninteresting. Bad people are, from the point of view of art, fascinating studies. They represent colour, variety and strangeness. Good people exasperate one’s reason; bad people stir one’s imagination’ (26 June 1890); issued in book-form (1891), with additional epigraphs [as infra.] Note also a letter to the Scots Observer (‘You may ask me, sire, why I should care to have the ethical beauty of my story recognises. I answer, simply, because it exists, because the thing is there.’ (All the foregoing [I, II, & III] in Neil Sammells, ‘Pulp Fictions’, in Irish Studies Review, Summer 1995, pp.40-41.)

Epigraphs to Dorian Gray incl. 1] ‘There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written, or badly written. That is all.’ 2] ‘The nineteenth century dislike of Realism is the rage of Caliban seeing his own face in a glass. The nineteenth century dislike of Romanticism is the rage of Caliban not seeing his own face in a glass.’ 3] ‘there is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written or badly written. That is all.’ 4] ‘No artist has ethical sympathies. An ethical sympathy in an artist is an unpardonable mannerism of style.’ 5] ‘Vice and virtue are to the artist materials for art.’ 6] ‘All Art is at once surface and symbol. Those who go beneath the surface do so at their own peril. Those who read the symbol do so at their peril.’ 6] ‘It is the spectator, and not life, that Art really mirrors.’ 7] ‘All art is quite useless.’ [Numbers added here.]

[ top ]

An Ideal Husband (1895): Sir Robert Chilton, friend of Lord Arthur Goring (the son of Lord Caversham), has exploited government secrets for financial gain in the Suez Canal Affair early in his political career; his secret is discovered by Mrs. Cheveley who threatens blackmail at the cost of his career as well as his marriage to Lady Chiltern, a figure of strict rectitude who cannot tolerate character flaws, especially in her ‘ideal’ husband. Both Chilterns turn to Lord Arthur while Mabel Chiltern, Sir Robert’s sister, looks on Lord Arthur as a potential husband for herself. Yet in order to be a successful blackmailer, one’s own reputation must be beyond reproach and, in the event, the blackmailer turns out to have stolen a bracelet from Lord Arthur’s cousin Mary Berkshire and Arthur sees her off, but not before she attempts to destroy Lady Chiltern with an ambiguous letter that the latter has addressed to Lord Arthur. At the conclusion of these transactions Lord Arthur reveals ‘the philosopher that underlies the dandy’ and proves himself ‘the first well-dressed philosopher in the history of thought’, resolving all difficulties with wise words about human love, tolerance and the dangers of idealisation. (Act. IV.) Finally, Lady Chiltern learns to accept her husband’s appetite for power and Lord Arthur proposes to Mabel Chiltern, undertaking - in Lord Caversham’s words - to become ‘an ideal husband.’

[ top ]

The Importance of Being Earnest (1895) - Summary I: Two young men, Algernon Moncrieff and Jack Worthing, JP, who is in love with Algernon’s cousin Gwendolen; Algernon does not realise that John was christened Ernest, though ‘Uncle Jack’ to his ward, Cecily; the men discover in conversation that they both pretend to be someone else when it suits them, Algernon has a useful invalid friend Bunbury, while John becomes his own wicked brother Ernest, under which name Gwendolen has accepted his marriage proposal; Cecily accepts Algernon who falsely tells her he is Ernest, a name she fancies; Lady Bracknell repudiates the proposal directed towards her charge Gwendolen; the ensuing confusions are resolved when it is discovered that Jack was indeed so named before being mislaid in the cloakroom of a London station by Miss Prism, a forgetful governess, and then adopted by Cecily’s father.

The Importance of Being Earnest (1895) - Summary II (Film version): comedy, black and white, 93 minutes, directed by Anthony Asquith (1952), starring Sir Michael Redgrave, Michael Denison, Dame Edith Evans, Dorothy Tutin, Margaret Rutherford, Joan Greenwood, Miles Malleson. Summary: Jack Worthing and Algernon Moncrieff - two wealthy and eligible bachelors of the 1890s - are hopelessly in love. The former with Gwendoline, who is the latter’s cousin. The latter with Cecily, who is the former’s ward. Due to Jack’s ignoble habit of representing himself as his imaginary brother, Ernest, when in town, and Algernon’s adoption of Ernest’s name and wicked reputation to speed his courtship of Cecily, both girls believe themselves to be engaged to the non-existent Ernest. When Jack discovers this, he goes into deep mourning, announcing that his brother has been killed by a severe chill in Paris ... but the girls see through this deception! Obliged to admit that neither is really called Ernest, the two men agree separately to be re-christened in that name to prove their devotion. They reckon, however, without the intervention of the formidable Lady Bracknell, Gwendolen’s mother and Algernon’s aunt, who opposes everything until Miss Prism, Cecily’s governess and a devoted family retainer, brings to light an old skeleton in the family cupboard and makes it clear that one of the men, is in fact ‘earnest’. (Video exhibited to private audience at 18h30 on Friday 11th May 2001 in the Conference Room at the Princess Grace Irish Library.)

The Ballad of Reading Gaol (1898): The ballad materially concerning the hanging in Reading Gaol of Trooper Thomas Woodridge for murder of his wife, an execution that took place during Wilde’s period of imprisonment there. Its chief themes are the tragic universality of the murderer’s crime (‘each man kills the thing he loves’); the possibility of Christian redemption (‘the man was one of those / Whom Christ came down to save’); and the futility of the prison system in general and capital punishment in particular (‘every prison that men build / Is built with bricks of shame’). Lines from the ballad appeared on his monument in Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris, ‘his mourners will be outcast men, / And outcasts always mourn.’

[ top ]

De Profundis (1905): The first edition of De Profundis, ed. Robert Ross, is less than half the MS letter written in January-March 1897 by Wilde, and handed to Ross on the day after leaving Reading Gaol; Ross made two typed copies, sent one to Douglas, the addressee (though the latter always denied having received it), and bequeathed the second to Vyvyan, who published it in full in 1949; Ross left the MS to the British Museum on condition that it was not read for fifty years; it is this version which serves as copy-type for the Rupert Hart-Davis, ed., Letters of Oscar Wilde (London 1962). See under Quotations, supra; also longer extracts, attached - or go to full-text copy in RICORSO Library, “Irish Classics”, via index, or direct.]

De Profundis (2): the work, written in 1896-97, skirts penitence and acknowledging faults (not those cited in the courtroom) while vindicating the author’s individuality (see Richard Ellmann, Oscar Wilde, p.xiii).

De Profundis (3): ‘Addressed to Wilde’s lover, Lord Alfred Douglas, and composed in Reading Gaol, it was later given the title “De Profundis” by Wilde’s friend and literary executor, Robert Ross. It was Ross’s severely abridged and sanitized version, published in 1905 and again 1908, which inaugurated the tradition of seeing “De Profundis” as the ‘apologia pro sua vita’ of a broken man. This edition takes account of this complex heritage by arguing that Wilde’s prison document may be seen not just as the basis of a letter (a typed copy of which may have been sent to Douglas) but also as an unfinished literary work which he intended for public consumption at some future date. Such a case is made by placing in the public domain, often for the first time, a number of different works, derived from different texts, each of which bears witness to Wilde’s multiple intentions for his prison document. These texts comprises of: the manuscript held in the British Library; the version of Wilde’s letter published by his son, Vyvyan Holland, from a typescript bequeathed to him by Robert Ross; hitherto unpublished witnesses to that typescript; and Ross’s editions, collated with each other. The commentary to this edition - again for the first time - sets Wilde’s story of his own life in “De Profundis” against the testimony of other players in his drama, including, most importantly, that of Douglas. In so doing, it exposes the partial nature of Wilde’s narrative, as well as the personal obsessions which animated it.’ (COPAC notice [Collected Works] - online; accessed 22.03.2010.)

De Profundis: The definitive edition of Wilde’s impassioned letter from Reading Gaol. Imprisoned in Reading Gaol in 1895 for his homosexuality, Oscar Wilde once defiantly wrote `I don’t defend my conduct, I explain it’. Wilde’s notorious liaison with the Marquess of Queensberry’s son, Lord Alfred Douglas (`Bosie’), had so inflamed the Marquess that he made public attacks on Wilde’s character. In return, Wilde sued for slander, an action which, to Wilde’s bitter astonishment, led to a series of scandalous trials and convictions. From his cell Oscar Wilde wrote De Profundis, the detailed and unsparing revelation of his love and tragedy. Each day he wrote a page at the behest of his warden who would then take it. Only upon his release was he given the full text to read and revise. This volume comprises the complete text of De Profundis, a letter from Wilde letter to Robert Ross, as well as The Ballad of Reading Gaol. It also features an essay by W.H. Auden which offers an insightful retrospective on Wilde, the text itself and the genre of epistolary literature more broadly. (COPAC notice on De Profundis, new edn., with notes by Rupert Hart-Davis, an essay by W. H. Auden and The ballad of Reading Gaol. (London: Duckworth 2017) - online; accessed 22.03.2010.)

De Profundis - “Epistola: in carcere et vinculis”, in The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde, Vol. 2, ed., Ian Small (2010): This volume presents for the first time the complete textual history of one of the most famous love letters ever written. Addressed to Wilde’s lover, Lord Alfred Douglas, and composed in Reading Gaol, it was later given the title “De Profundis” by Wilde’s friend and literary executor, Robert Ross. It was Ross’s severely abridged and sanitized version, published in 1905 and again 1908, which inaugurated the tradition of seeing De Profundis as the apologia pro sua vita of a broken man. This edition takes account of this complex heritage by arguing that Wilde’s prison document may be seen not just as the basis of a letter (a typed copy of which may have been sent to Douglas) but also as an unfinished literary work which he intended for public consumption at some future date. Such a case is made by placing in the public domain, often for the first time, a number of different works, derived from different texts, each of which bears witness to Wilde’s multiple intentions for his prison document. These texts comprise: the manuscript held in the British Library; the version of Wilde’s letter published by his son, Vyvyan Holland, from a typescript bequeathed to him by Robert Ross; hitherto unpublished witnesses to that typescript; and Ross’s editions, collated with each other. The commentary to this edition - again for the first time - sets Wilde’s story of his own life in ’De Profundis’ against the testimony of other players in his drama, including, most importantly, that of Douglas. In so doing it exposes the partial nature of Wilde’s narrative, as well as the personal obsessions which animated it. The commentary also demonstrates a hitherto unnoticed element of Wilde’s work, the extent and nature of its richly layered intertextuality and its similarity, in its compositional practices, to many of his earlier works. (COPAC - online; accessed 08.12.2017.)

See also Colm Tóibín, ed. & intro.,, De Profundis and Other Prison Writings [Penguin Classics] (Penguin Books 2103), xxxii, 266pp. edited and introduced by Colm Tóibín. At the start of 1895, Oscar Wilde was the toast of London, widely feted for his most recent stage success, An Ideal Husband. But by May of the same year, Wilde was in Reading prison sentenced to hard labour. De Profundis is an epistolic account of Oscar Wilde’s spiritual journey while in prison, and describes his new, shocking conviction that ‘the supreme vice is shallowness’. This edition also includes further letters to his wife, his friends, the Home Secretary, newspaper editors and his lover Lord Alfred Douglas - Bosie - himself, as well as ‘the Ballad of Reading Gaol’, the heart-rending poem about a man sentenced to hang for the murder of the woman he loved. This Penguin edition is based on the definitive Complete Letters, edited by Wilde’s grandson Merlin Holland. Colm Toibin’s introduction explores Wilde’s duality in love, politics and literature. This edition also includes notes on the text and suggested further reading. Oscar Wilde was born in Dublin. His three volumes of short fiction, The Happy Prince, Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime and A House of Pomegranates, together with his only novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray, won him a reputation as a writer with an original talent, a reputation enhanced by the phenomenal success of his society comedies - Lady Windermere’s Fan, A Woman of No Importance, An Ideal Husband and The Importance of Being Earnest. Colm Tóibín is the author of five novels, including The Blackwater Lightship and The Master, and a collection of stories, Mothers and Sons. His essay collection Love in a Dark Time: Gay Lives from Wilde to Almodovar appeared in 2002. He is the editor of The Penguin Book of Irish Fiction.

[ top ]

Wilde’s people

Aristotle: Wilde inscribed the following sentence in his copy of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics: ‘Man makes his ends for himself out of himself: no end is imposed by external considerations, he must realise his true nature, must be what nature orders, so must discover what his nature is.’ The inscription is dated ‘Magdalen College 1877 October’. (See Richard Ellmann, Oscar Wilde, 1987; Penguin 1988, p.60.)

Giordano Bruno (1): ‘Soul and body, body and soul - how mysterious they were! There was animalism in the soul, and the body had its moments of spirituality. The senses could refine, and the intellect could degrade. Who could say where the fleshly impulse ceased, or the psychical impulse began? How shallow were the arbitrary definitions of ordinary psychologists! And yet how difficult to decide between the claims of the various schools! Was the soul a shadow seated in the house of sin? Or was the body really in the soul, as Giordano Bruno thought? The separation of spirit from matter was a mystery, and the union of spirit with matter was a mystery also.’ (The Picture of Dorian Gray, Eveleigh Nash & Grayson Ltd. 148 The Strand, London [1928], p.87; see full text in RICORSO Library, “Irish Classics”, via index or attached Chap. 4].)

Giordano Bruno (2): ‘Dullness is always an irresistible temptation for brilliancy, and stupidity is the permanent Bestia Trionfans that calls wisdom from its cave. To an artist so creative as the critic, what does subject-matter signify? No more and no less than it does to the novelist and the painter. Like them, he can find his motives everywhere. Treatment is the test. There is nothing that has not in it suggestion or challenge.’ (“The Critic as Artist”, Intentions, 1891; rep. in The Works of Oscar Wilde, London: Galley Press 1987, pp.984-998, p.966 - see longer extract - as attached.) [Note that Bestia Trionfans is the title of a work of Giordano Bruno.)

Giordano Bruno (3): ‘Nor, again, is the critic really limited to the subjective form of expression. [...] He may use dialogue [...] Dialogue, certainly, that wonderful literary form which, from Plato to Lucian, and from Lucian to Giordano Bruno, and from Bruno to that grand old Pagan in whom Carlyle took such delight, the creative critics of the world have always employed, can never lose for the thinker its attraction as a mode of expression. [...] By its means he can exhibit the object from each point of view, and show it to us in the round, as a sculptor shows us things, gaining in this manner all the richness and reality of effect that comes from those side issues that are suddenly suggested by the central idea in its progress, and really illumine the idea more completely, or from those felicitous after-thoughts that give a fuller completeness to the central scheme, and yet convey something of the delicate charm of chance.’ (“The Critic as Artist”, Intentions, 1891; rep. in Works of Oscar Wilde, London: Galley 1987, p.985; see full text version [Pt. II] in RICORSO Library, “Irish Classics” - via index or attached.)

G. B. Shaw: Shaw wrote to Wilde, ‘We are both Celtic and I like to think that we are friends.’ (Rupert Hart-Davis, Letters, of Oscar Wilde, 1962, p.332. And note: Shaw wrote a ‘Preface’ to Frank Harris, Oscar Wilde (1938 edn.), written 25 years after the first edn., and defending Harris against Sherard, a writer who has attacked his biography as an ‘imposture’ although Shaw discovers the same thing that he objects to said in a biography of his own - viz. the claim that Wilde died of syphilis, which Sherard at first disputed, and then endorsed in his interview with the gullible American biographer Boris Brasol of 1935.

[ top ]

| Marquess of Queensberry - letter to his son Alfred Lord Douglas |

| Alfred, Your intimacy with this man Wilde must either cease or I will disown you and stop all money supplies. I am not going to try and analyse this intimacy, and I make no charge; but to my mind to pose as a thing is as bad as to be it. With my own eyes I saw you in the most loathsome and disgusting relationship, as expressed by your manner and expression. Never in my experience have I seen such a sight as that in your horrible features. No wonder people are talking as they are. Also I now hear on good authority, but this may be false, that his wife is petitioning to divorce him for sodomy and other crimes. Is this true, or do you not know of it? If I thought the actual thing was true, and it became public property, I should be quite justified in shooting him on sight. Your disgusted, so-called father, |

|

Available at Univ. of Missouri-Kansas City - online; accessed 23.02.2013. |

| Queensberry’s letter to the Star, April 25, 1895 |

|

| Queensberry’s note to Wilde after the libel trial |

|

| Available at Univ. of Missouri-Kansas City - online; accessed 23.02.2013. |

[ top ]

G. K. Chesterton: Chesterton distinguished between ‘the real epigram which [Oscar Wilde] wrote to please his own wild intellect, and the sham epigram which he wrote to thrill the tamest part of our tame civilisation’, and speaks of ‘the charlatan’ aspect of his genius. (Essay, Daily News, 1909; collected in A Handful of Authors, 1953; cited in P. J. Kavanagh, “Bywords”, Times Literary Supplement, 21 Sept. 2001, p.16.)

[ top ]

James Joyce: the phrase, ‘in a relation to life than which none can be more immediate’ which is to be found in Stephen Hero [1944] echoes another in Oscar Wilde’s An Ideal Husband, viz., ‘he stands in immediate relation to modern life, makes it indeed, and so masters it’ (Lord Goring, Act III). Note also Mrs Cheveley’s remarks on her business with Sir Robert Chiltern [to Lord Goring:] “Oh, don’t use big words. They mean so little. It is a commercial transaction that is all’ (Ibid., Act IV; The Works of Oscar Wilde, London: Galley Press 1987, p.519; idem.), and cf. ‘Those big words that make us so unhappy’, in Joyce’s review of William Rooney’s poems. (Critical Writings, NY: Viking Press 1966, p.87.) [See further under James Joyce, Notes > Oscar Wilde, supra.]

Lord Alfred Douglas [1], Oscar Wilde: A Summing-Up (London: Richards Press, 1940; reiss. 1950): Note that Lord Douglas at his most self-righteous in a passage on the influence of J. H. Mahaffy on Wilde [see under Mahaffy, supra.] End papers cite Four Plays (7th printing); The Picture of Dorian Gray (4th); De Profundis [1st]; Salome [sic] (2nd); The Ballad of Reading Gaol (4th); Intentions (3rd); Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime and other stories [1st]; A House of Pomegranites with The Happy Prince [1st] & Poems (in preparation).

Lord Alfred Douglas [2]: Note items written by Douglas held in the Suppressed Safe of the British Library, including Letters to my Father-in-Law, 1 (London 1914) [SS. A. 34], being an attack on Colonel Frederic Hambleton Custance for engaging solicitor George Lewis as “as a catspaw” in the interests of Robert Ross “the notorious Sodomite” and Ross’s secretary Christopher Millard. Letter is headed 19, Royal Avenue: Sloane Square, S.W, March 20 1914; copy in the General Catalogue [C.194.a.235]. Also The Rossiad (London 1916) [SS. B. 16], presumably a libelous satire on Robert Ross, Oscar Wilde’s friend and executor; a copy of the second edition as Galashiels (Robert Dawson & Son [1916], 15pp., 8°, is shelved at X.909/20162; a fourth edn. (Galashiels 1921), pp. 23 shelved at X.909/24366. [see Scissors and Paste online; accessed 30.04.2010.]

| Alfred Lord Douglas (1870-1945), “Impressions de Nuit - London” | |

| See what a mass of gems the city wears Upon her broad live bosom! row on row Rubies and emerads and amethysts glow. See! that huge circle like a necklace, stares With thousands of bold eyes to heaven, and dares The golden stars to dim the lamps below, And in the mirror of the mire I know The moon has left her image unawares. That’s the great town at night: I see her breasts, Pricked out with lamps they stand like huge black towers. I think they move! I hear her panting breath. And that’s her head where the tiara rests. And in her brain, through lanes as dark as death, Men creep like thoughts ... The lamps are like pale flowers. |

|

| — See The Other Pages - online [accessed 24.09.2010]. | |

Cf. also his poems -

| “Two Loves” | |

| [...] | |

| I fell a-weeping, and I cried, “Sweet youth, Tell me why, sad and sighing, thou dost rove These pleasant realms? I pray thee speak me sooth What is thy name?” He said, “My name is Love.” Then straight the first did turn himself to me And cried, “He lieth, for his name is Shame, But I am Love, and I was wont to be Alone in this fair garden, till he came Unasked by night; I am true Love, I fill The hearts of boy and girl with mutual flame.” Then sighing, said the other, “Have thy will, I am the Love that dare not speak its name.” [End] |

|

| “In Praise of Shame” | |

|

Last night unto my bed bethought there came And afterwords, in radiant garments dressed |

|

[ top ]

Lord Alfred Douglas [3]: See remarks on Wilde’s De Profundis and Douglas’s reprisal on Douglas on the “Viereck Project” website in Wikispace. G. S. Viereck’s provided an account of his meeting and rapport with Douglas, together with his estimate of the Wilde-Bosie relationship, in “A Slim Gilt Soul” an undated typescript held in the University of Iowa Special Collections ( George S. Viereck Collection, Box 4, Folder 25): Viz., ‘Wilde was an Irish Protestant with a middle class conscience and pronouncedly Catholic leanings who vainly tried to make himself believe he was a Greek. Douglas was a Greek who vainly imagined himself to be a devout Catholic. [“devout” is pencilled into the typewritten manuscript as an afterthought.] The boot does not fit. It is easy to discern under the monkish gown the cloven hoof of Pan.’ (typescript p.10.) Viereck on Wilde suggests a profound sympathy with the Irish writer: “Wilde is splendid. I admire, nay, I love him. He is so deliciously unhealthy, so beautifully morbid and evil. I love the splendor of decay, the foul beauty of corruption. What I hate is the inquisitive, cold, freezing rays of the sun. Day is nausea, day is dullness, day is prose. Night beauty, love, splendor, poetry, wine, scarlet, rape, vice and bliss. I love the night.” (Quotin Elmer Gertz, Odyssey of a Barbarian, NY: Prometheus Books 1978, p.37.) [See Viereck Project, online > Lord Alfred Douglas; accessed 14.09.2010.)

William Wilde [“Willie”; b. 26.09.1852], a writer for the Daily Telegraph, marries Mrs Frank Leslie, an America Widow, 1891, but is divorced when detected in adultery (d.1899, aetat. 46); a dg. of Willie, Dorothy, died of heroin in Paris, having befriended Djuna Barnes. Willie’s unwashed appearance inspire Oscar to make the quip, ‘He sponges on everyone but himself.’

Rupert Hart-Davis, ed., Letters of Oscar Wilde (London 1962), notes that the edition De Profundis (1905), ed. by Robert Ross, is less than half the MS letter written by Wilde in January-March 1897 and handed to Ross on the day after leaving Reading Gaol. Ross made two typed copies, sent one to Douglas, the addressee (though the latter always denied having received it), and bequeathed the second to Vyvyan, who published it in full in 1949; Ross left the MS to the British Museum on condition that it was not read for fifty years; it is this version which serves as copy-type for the Letters . There are errors in the typescripts due to aural mistakes in dictation to typist, and similar causes.

Princess Alice [Grimaldi] of Monaco: ‘Vyvyan Holland wrote in his souvenirs: “one of the people who had remained loyal to my father was Princess Alice of Monaco. She had always protested against the inhumanity of his treatment.”’ (Correspondence with RICORSO from Alain Quella-Villeger, 11.06.2018.) Note that his House of Pomegranites (1891) was dedicated to her.

[ top ]

Robert Donovan, Prof. of English at UCD, refused licence to student production of The Importance of Being Earnest in 1930 on the grounds that it seemed to have the students going ‘out under the banner of Oscar Wilde.’

Lionel Johnson: Johnson wrote a poem in Latin thanking Wilde for the copy of Dorian Gray that he received from him: ‘Beneditus sis, Oscare! ... .’ [See further under Johnson, q.v.]

[ top ]

Walter Pater (1): ‘Art for Art’s Sake’, the phrase so often associated with Wilde, was actually coined by Swinburne and not by Pater, his Oxford tutor and the author of The Renaissance which he so much admired, as often alleged. But see the passage in “The Decay of Lying” in which Wilde writes: ‘[...] Art never expresses anything but itself. This is the principle of my new aesthetics; and it is this, more than that vital connection between form and substance, on which Mr. Pater dwells, that makes music the type of all the arts.’ (The Works of Oscar Wilde, London: Galley Press 1987, p.926.)

Pater on Giordano Bruno: ‘Bruno himself tells us, long after he had withdrawn himself from it, that the monastic life promotes the freedom of the intellect by its [235] silence and self-concentration. The prospect of such freedom sufficiently explains why a young man who, however well found in worldly and personal advantages, was conscious above all of great intellectual possessions, and of fastidious spirit also, with a remarkable distaste for the vulgar, should have espoused poverty, chastity, obedience, in a Dominican cloister. What liberty of mind may really come to in such places, what daring new departures it may suggest to the strictly monastic temper, is exemplified by the dubious and dangerous mysticism of men like John of Parma and Joachim of Flora, reputed author of the new “Everlasting Gospel”, strange dreamers, in a world of sanctified rhetoric, of that later dispensation of the spirit, in which all law must have passed away; or again by a recognised tendency in the great rival Order of St. Francis, in the so-called “spiritual” Franciscans, to understand the dogmatic words of faith with a difference.’(“Giordano Bruno, Paris, 1586”, in Fortnightly Review, Vol. XLVI, No. CCLXXII (1 August 1889), pp.234-44; pp.235-36; available at Gutenberg Project at Internet Archive - online; see also digital copy in RICORSO Library, “Critics > International” - attached.)

Walter Pater (2): ‘Even the work of Mr. Pater, who is, on the whole, the most perfect master of English prose now creating amongst us, is often far more like a piece of mosaic than a passage in music, and seems, here and there, to lack the true rhythmical life of words and the fine freedom and richness of effect that such rhythmical life produces.’ (“Critic as Artist”; in The Works of Oscar Wilde, London: Galley Press 1987, p.955.)

[Note further remarks on blind Homer and Milton - viz., ‘The Greeks, upon the other hand, regarded writing simply as a method of chronicling. Their test was always the spoken word in its musical and metrical relations. [...] When Milton could no longer write he began to sing. Who would match the measures of Comus with the measures of Samson Agonistes, or of Paradise Lost or Regained?]*’

| See Pater page of New NDB - available online. |

Walter Pater (3): ‘We cannot go back to the saint. There is far more to be learned from the sinner. We cannot go bacl to the philosopher, and the mystic leads us astray. Who, as Mr. Pater suggests somewhere, would exchange the curve of a single rose-leaf for that formless intangible Being which Plato rates so high?’ (“Critic as Artist”; in The Works of Oscar Wilde, London: Galley Press 1987, p.979.)

See also comments on Wilde’s indebtedness to Whistler, Flaubert and Gautier, and his receipt of a loan of Pater’s copy of Flaubert’s story Salomé while at Oxford, in Ciaran Murray, Disorientalism (2009) - as in Commentary, supra.

Walter Pater (3): ‘Nor, again, is the critic really limited to the subjective form of expression. The method of the drama is his, as well as the method of the epos. He may use dialogue, as he did who set Milton talking to Marvel on the nature of comedy and tragedy, and made Sidney and Lord Brooke discourse on letters beneath the Penshurst oaks; or adopt narration, as Mr. Pater is fond of doing, each of whose Imaginary Portraits - is not that the title of the book? [...].’ (“The Critic as Artist”, in Works of Oscar Wilde, Galley Press 1987, p.985.)

Water Pater (4) - the word imperishable [in Yeats and Joyce] ...Marius the Epicurean (1885): ‘[T]owards such a full or complete life, a life of various yet select sensation, the most direct and effective auxiliary must be, in a word, Insight. Liberty of soul, freedom from all partial and misrepresentative doctrine which does but relieve one element in our experience at the cost of another, freedom from all embarrassment alike of regret for the past or calculation on the future […]’ (Marius the Epicurean, 2 vols. [1885] London: Macmillan 1921, p.123.)

| Pater’s “Sir Thomas Browne” [1878], in Appreciations; with an Essay on Style (London: Macmillan 1910) |

| ‘What a fund of open-air cheerfulness, there! in turning to sleep. Still, even when we are dealing with a writer in whom mere style counts for so much as with Browne, it is impossible to ignore his matter; and it is with religion he is really occupied from first to last, hardly less than Richard Hooker. And his religion, too, after all, was a religion of cheerfulness: he has no great consciousness of evil in things, and is no fighter. His religion, if one may say so, was all profit to him; among other ways, in securing an absolute staidness and placidity of temper, for the intellectual work which was the proper business of his life. His contributions to “evidence,” in the Religio Medici, for instance, hardly tell, because he writes out of view of a really philosophical criticism. What does tell in him, in this direction, is the witness he brings to men’s instinct of survival - the “intimations of immortality,” as Wordsworth terms them, which [159] were natural with him in surprising force. As was said of Jean Paul, his special subject was the immortality of the soul; with an assurance as personal, as fresh and original, as it was, on the one hand, in those old half-civilised people who had deposited the urns; on the other hand, in the cynical French poet of the nineteenth century, who did not think, but knew, that his soul was imperishable. He lived in an age in which that philosophy made a great stride which ends with Hume; and his lesson, if we may be pardoned for taking away a “lesson” from so ethical a writer, is the force of men’s temperaments in the management of opinion, their own or that of others; - that it is not merely different degrees of bare intellectual power which cause men to approach in different degrees to this or that intellectual programme. Could he have foreseen the mature result of that mechanical analysis which Bacon had applied to nature, and Hobbes to the mind of man, there is no reason to think that he would have surrendered his own chosen hypothesis concerning them. He represents, in an age, the intellectual powers of which tend strongly to agnosticism, that class of minds to which the supernatural view of things is still credible. The non-mechanical theory of nature has had its grave adherents since: to the non-mechanical theory of man - that he is in contact with a moral order on a different plane from the [160] mechanical order - thousands, of the most various types and degrees of intellectual power, always adhere; a fact worth the consideration of all ingenuous thinkers, if (as is certainly the case with colour, music, number, for instance) there may be whole regions of fact, the recognition of which belongs to one and not to another, which people may possess in various degrees; for the knowledge of which, therefore, one person is dependent upon another; and in relation to which the appropriate means of cognition must lie among the elements of what we call individual temperament, so that what looks like a pre-judgment may be really a legitimate apprehension. “Men are what they are,” and are not wholly at the mercy of formal conclusions from their formally limited premises. Browne passes his whole life in observation and inquiry: he is a genuine investigator, with every opportunity: the mind of the age all around him seems passively yielding to an almost foregone intellectual result, to a philosophy of disillusion. But he thinks all that a prejudice; and not from any want of intellectual power certainly, but from some inward consideration, some afterthought, from the antecedent gravitation of his own general character - or, will you say? from that unprecipitated infusion of fallacy in him - he fails to draw, unlike almost all the rest of the world, the conclusion ready to hand.’ |

| pp.160-61; available at Gutenberg Project [online]. |

|

| See also: |

| Plato and Platonism - IX: The Republic, Works of Pater (Cambridge UP 1901) |

| The Republic, as we may realise it mentally within the limited proportions of some quite imaginable Greek city, is the protest of Plato, in enduring stone, in law and custom more imperishable still, against the principle of flamboyancy or fluidity in things, and in men’s thoughts about them. (p.235.) |

| There is a copy of Marius the Epicurean (1885) - Chapter VIII: “Animula Vagula” in RICORSO > Library > Classics - under Walter Pater - as attached. |

[ top ]

Helena Callanan - was author of a poem called “The Shamrock” which was later published in The Weekly Sun on on Sunday, August 5th 1894 and attributed there to Oscar Wilde. This was copied by The New York Sun on August 19th of the same year and was spotted there by a Rev. William J. McClure who wrote to the editor calling attention to a copy of the poem in his album taken from The Cork Weekly Herald of the early 1880s. Mr. McClure pointed out some variations in the poem and asked how Wilde’s name came to be associated with it. In late September Wilde himself wrote to the Pall Mall Gazette (20 Sept. 1894) rebutting the accusation of plagiarism. An assistant editor of The Weekly Sun wrote on the following day that a correspondent had sent in the poem with the name of Mr. Oscar Wilde appended and with a a covering letter explaining that he had copied the poem from an old Irish newspaper, remarking his surprise at such a piece “so fine and tender” coming from the “flaneur and a cynic” Oscar Wilde. (Information contributed by Frank Callery; for a copy of his full remarks, see under Callanan - as infra.)

John Todhunter: Constance Wilde appeared in Helen at Troas (1886), Todhunter’s spectacle-play performed at Hengler’s Circus, in which she played the part a figure in the Parthenon frieze.

Gilbert & Sullivan : Gilbert and Sulivan caricatured Wilde in Patience (1881) as the preposterous aesthete as Bunthorpe with the lines: ‘A most intense young man, / A soulful-eyed young man; / An ultra-poetical super-aesthetical, / Out-of-the-way young man’ - ironicallly preparing the way for his ten-month tour of the United States of America.

Sir Edward O’Sullivan: O’Sullivan recorded young Wilde’s remarks in the course of a discussion of an ecclesiastical scandal of the day: ‘Oscar was present, and full of the mysterious nature of the Court of Arches: he told us there was nothing he would like better in after life than to be the hero of such a cause celèbre and go down to posterity as the defendant in such a case as Regina versus Wilde.’ (Quoted in Merlin Holland, The Wilde Album, 1997, p.26.)

André Gide: Wilde told André Gide: ‘I have put only my talent into my works. Ihave put all my genius into my life.’ (Gide, in Oscar Wilde: A Study, trans. by Stuart Mason, Oxford: Holywell Press 1905.)

W. P. Frith: Frith was mocked by Wilde for his photographic-style of painting in ‘The Grosvenor Gallery’, a London exhibition review contributed to Dublin University Magazine, 90 (July 1877), p.125. In the same review Wilde also mentioned the Irish painters F. W. Burton and Richard Doyle. See also Wilde, ‘The Rout of the RA’, in Court and Society Review, Vol. IV (27 April 1887); rep. in Ellmann, ed., The Artist as Critic (London: W. H. Allen 1970).

[ top ]

Sundry topics

Oscar’s ambitions: A handwritten questionnaire filled by Wilde as a student in the form of in a two-page entry of an ‘Album for Confessions or Tastes, Habits and Convictions’, 1877, declared that his most distinctive characteristic was ‘inordinate self-esteem’; and listed self among four favorite poets; most disliked in others ‘vanity, self-esteem, conceit’; Wilde said his idea of misery would be ‘living a poor and respectable life in an obscure village’; Further, Q: ‘What are the sweetest words in the world? A: ‘Well done!’; Q: ‘What are the saddest words?’ A: ‘Failure.’ Q: ‘What is your dream?’ A: ‘Getting my hair cut.’ A: ‘What is your bête noir?’ A: ‘A thorough Irish Protestant.’ Q: ‘What is your idea of happiness?’ A: ‘Absolute power over men’s minds, even if accompanied by toothache.’ Q: ‘If not yourself, who would you rather be?’ A: ‘A cardinal of the Catholic church’; put on sale by descendant of Adderley Millar Howard, impresario and actor who collected the questionnaires; includes a photograph of the 23-year-old Wilde; auction at Christie’s (London), 6 June; estimated price, $4,800 (noticed in Irish Times ; copied from WWW Associated Press Bulletin).

Dublin journals: Wilde published early poems and reviews in Kottabos (1876), and The Irish Monthly, ed. Fr. Matthew Russell (do.). His reviews incl. Froude’s Two Chiefs of Dunboye, Graves’s ‘Fr. O’Flynn,’ and Yeats’s Wanderings of Oisin.

Social graces: In London, Wilde became confidant of such social ladies as Duchess of Westminster, Lady Desart and Lady Lonsdale. Note that he subscribed the signature ‘Oscar F. O’F. Wilde’ to his correspondence with friends in Oxford.

Plagiarism? Oscar Wilde commonly annexed [plagiarised] whole passages from works such as the biographies of Thomas Chatterton for inclusion in his own lectures series. (See Jerusha McCormack, review of Thomas Wright, A Wilde Read: Oscar’s Books, in The Irish Times, 6 Sept. 2008, Weekend, p.11.)

Lost Pastoral: Karl Beckson & Bobby Fong print Wilde’s last (and lost) pastoral found in the Harry S. Dickey Collection, MS 72, Milton S. Eisenhower Library at Johns Hopkins Univ. (See Times Literary Supplement, 17 Feb. 1995). The article incls. a photo port. of Wilde taken by Napoleon Sarony (New York, 1882), and rep. from Camera Portraits, Photographs from the National Portrait Gallery, ed. Malcolm Rogers (Nat Port. Gall [q.d.]).

Acallamh na Senorach [Colloquy of the Ancients]: In Acallamh na Senorach Cailte says: ‘Fair Youth was the horn Oscar brought to the feast, / He, whom many girls smiled on, was also the joy of men’s eyes.’ (Roe/Dooley trans.).

Adapted Wilde: Peter Harness, a DPhil student at Oriel College, adapted The Picture of Dorian Gray for the Oxford Playhouse, November 13-16 2002. Note that “The Selfish Giant” has been adapted for children in a musical version with lyrics by David Perkins and additional lyrics by Caroline Dooley; large variable cast; simple settings; libretto and piano vocal score; optional band parts on hire (flute, Trumpet, bass guitar, Glockenspeil, &c.); two succcessful seasons at Yvonne Arnaud Th., Guildford, by Youth Theatre Act 1 (1995, 2002).

Oscar in drag? (1): A photograph presumed to be of ‘Oscar Wilde im Kostüm als Salome’, taken from the Collection Guillot de Saiz, H. Roger Viollet, Paris, appears in the bibliography of Ellmann’s essay on Wilde in Jürgen Schneider & Ralf Sotscheck, Ireland: Eine Bibliographie selbständiger deutschsprachiger (Verlag de Georg Büchner Buchhandlung 1989, pp.214-34, p. 219), is now know to be falsely identified with him. In ‘Wilde as Salomé?’, in Times Literary Supplement ( 22 July 1994), p.14 [backpage], Merlin Holland questions authenticity of the photograph of Wilde as Salomé, printed by Ellmann in Oscar Wilde [1987] remarking that John Stokes wrote to London Review of Books (Feb. 1992), provisionally identifying subject of picture as Leonara Sengera [sic], a signed photo of whom appeared in the same Paris collection (Roger-Viollet). Holland runs to earth in a periodical Buhne und Welt pictures of soprano Alice Guszalewicz playing in Strauss’s Salomé in Budapest in 1906 in identical clothing. He then establishes the source of confusion between Sengern and Guszalewicz: Leonore Sengern played Herodias to Pala Donges’s I, in Leipzig, five weeks before Guszalewicz (née Farkas) appeared in the opera, on July 2 1906. Notes the first appearance of ‘Wilde as Salomé in Le Monde (20 March 20 1987), two weeks before Ellmann’s death; Ellmann was notified by his editor Catharine Carver and was delighted. Further, Elaine Showalter reproduced the photo in Sexual Anarchy (1990) in support of her reading of Iokanaan as ‘veiled homosexual desire’ while Marjorie Garber used it in Vested Interests (1992) to illustrate Salomé’s story as a transvestite dance. Even the Roger-Viollet archive recaptioned it in accord with to Ellmann’s book (later re-emending to ‘Wilde?’). [See also Elaine Showalter, ‘It’s Still Salome’, in Times Literary Supplement (2 Sept. 1994), pp.13-14 - as in Commentary, supra.]

Oscar in drag? (2): There exists a childhood photograph of Oscar Wilde in a dress which is sometimes taken to mean that his mother treated him a girl, thus inducing in him a mentality that found its fulfilment in the homosexual bias of his adult sexuality. In fact the custom was general, probably for the practical reason that changing nappies as more convenient in a dress than any kind of pants or trousers. (A photograph of Albert le Brocquy as a child of one or two in my possession demonstrates this norm: BS.) The prevalence of an equally wide-spread conjecture that the dressing of little boys in skirts intended to ‘ward off faeries’ is reflected in the Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy and may therefore have been part of the folk-lore - or urban myths - of Ireland and Wilde’s social class in Dublin. On the last page of a paper on Irish ethnography by A. C. Haddon and C. R. Browne, there is a photograph of Aran boys, seemingly aged 8 or 9, who are wearing dress-like garb - though one has plainly got trousers under that apparel. The caption reads: ‘Group of Three Aran Boys. We have been informed that the reason why the small boys are so dressed is to deceive the devil as to their sex. [The negative was kindly lent to us by Mr. N. Colgan.]’ See Haddon & Browne, ‘The Ethnography of the Aran Islands’, County Galway, in Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy (1889-1901), Vol. 2 [1891-93], pp.768-830; p.826 [online at JSTOR; accessed 18.05.2010; and see further under Liam O’Flaherty, remarks on David O’Callaghan, the model for Skerrett (1932)].

Wilde in Omaha: Ron Hansen, She Loves Me Not (2012), a story collection, opens with an account of Wilde’s visit to Omaha in March 1882. See New York Times review by Sven Birkerts: ‘[...] The first story, “Wilde in Omaha,” is, as its title suggests, a playful reimagining of Oscar Wilde’s actual visit to that city in March of 1882. Recounted by a bumbling, fame-besotted journalist, the British writer’s short stay among the arts-avid, cornfed Nebraska bourgeoisie becomes a delightful anthology of some of this famed raconteur’s best bits. For Wilde will make no conversational response to any question that isn’t an epigram, as often as not a well-known one. Hansen’s setup lines can be almost groaningly obvious. When a Mr. Rosewater of The Daily Bee asks him, apropos of nothing, “Are you a hunter?” Wilde gets to deliver one of his celebrated bons mots: “Are you asking if I gallop after foxes in the shires? Indeed not. I consider that the unspeakable in pursuit of the uneatable.” Didn’t Monty Python run a similar shtick some years before? They did. But Hansen isn’t pretending otherwise.’ (See Birkerts, review, in New York Times, 9 Nov. 2012, “Books” - online; accessed 09.11.2012.

[ top ]

Miss Prism’s misprision: Michael J. O’Shea [Fayetteville State U, ret.) writes in Facebook [02.09.2017] that Lawrence O’Donnell reported on his programme The Last Word (MSNBC) on the previous night having learned that an additional charge might be made against the Vice-President [Pence] for “misprision of a felony” - an offence involving ‘concealment of a crime of which the accused had been aware’. To this O’Shea adds that the name of the character Miss Prism in The Importance of Being Earnest has echoes of the word misprision which seem apposite to him ‘because Lætitia Prism has concealed her having mislaid the handbag in which she has absentmindedly placed (spoiler alert) Ernest Moncrieff, whom we had known until the final act as John (Jack) Worthing.’ His post includes an image of Margaret Rutherford as Ms. Lætitia Prism in The Importance of Being Earnest (1952).

|

The Importance of Being Earnest (1952) |

Wilde on America: The epigram about America often ascribed to Wilde to the effect that ‘America is the only nation in history which miraculously has gone from barbarism to decadence without the usual interval of civilisation’ was actually coined by the French premier and sometime journalist, Georges Clemenceau. (See Quote Investigator - online; accessed 18.09.2025.)

Clemenceau’s sentence - aimed at the Hoover Administration in American during the Bootlegging Era - reads: “America is the only nation in history which miraculously has gone directly from barbarism to degeneration [sic] without the usual interval of civilization.” (Quoted by Hans Bendix, Danish illustrator and cartoonist, in a essay for The Saturday Review of Literature in 1945. (‘Degeneracy’ for ‘decadence’ appears to be Bendix’s variation.)

The erroneous attribution to Wilde is given in The Sunday Times Book of Humorous Quotations (2008) without bibliographical or other references - and it is not to be found in the text of Wilde's lecture on Impressions of American which was written following his trip there in 1882 and was printed as a book with an introduction by Stuart Mason in 1906. The piece is included in Richard Ellmann, ed., Critical Writings of Oscar Wilde (1972) and is available at both Gutenburg Project and Internet Archive.

| [ back ] | [ top ] |