Life

| 1881-1972 [prop. Pádraic; var. Patrick McCormac Colum; orig. Columb], b. 8 Dec., eldest son and first child of Patrick and Susan [McCormack] Columb, a school-teacher master of the Longford workhouse, who travelled to America for some years on losing his post in Longford, working in the Colorado gold-fields, 1887; the children raised in Co. Cavan, with their grandmother; father returned in 1891, when family moved to Sandycove nr. Dublin, where his father next worked as station master [asst. mgr.] at Glasthule/Sandycove railway station; Padraic ed. Glasthule National School (Dun Laoghaire, Co. Dublin); suffered the death of his mother, 1897; remained in Dublin with one brother while his father and the remaining children returned to Longford; finished school and gained employment by examination for post as a clerk in the Irish Railway Clearing House, Dublin, 1898-1904; sent part of early play, Broken Soil, to secretary of Inghindhe na hÉireann and hence introduced to the Fay brothers; published poetry in United Irishman from 1902; joined National Theatre Society; appeared in AE’s Deirdre (1902), as a pupil in The Hour Glass and as a cripple in The King’s Threshold, both by Yeats, 1903; |

| his play Broken Soil produced the National Theatre, 1903; another play, The Saxon Shillin’ [1903], had for a three-night’s run in May 1903 [var. 1902], and took the Cumann na nGael drama prize but was later rejected by the Abbey in 1914 on the grounds of "dramatic problems" but probably for its anti-recruiting tendency, causing the resignation of Arthur Griffith - who had already published it in United Irishmen - from the Irish Literary Theatre [?likewise Maud Gonne]; received a five-year scholarship equal to his clerk’s income [£40 p.a.] from Thomas H[ughes] Kelly, a wealthy American living in Dublin, to support him in his writing, 1904; altered his name to “Colum”; became a signatory of Abbey Theatre charter; his peasant realist plays The Land (1905) and The Fiddler’s House (1907), the earliest of the genre, set the trend for commercially successful Abbey drama; wrote to the papers in defence of his father’s riotous conduct at the premier of Synge’s Playboy, and refused Lady Gregory’s offer to pay the fine, 1907; his play Thomas Muskerry produced at the Abbey, Dublin, and in New York, 1910; also The Desert (1912) and a new play, The Betrayal (Manchester 1913; Pittsburgh 1914); |

| [ top ] |

| co-edited the Irish Review with Thomas MacDonagh, David Houston, Mary Catherine Gunning Maguire [“Molly” - later Mary Colum], et al.; taught occasionally at Patrick Pearse’s St. Enda’s College; m. Mary Maguire [q.v.], 1912; settled in Donnybrook, where the couple held Tuesday ‘evenings’ - and later in Howth village; issued A Boy in Eirinn (NY 1913, London 1915); joined in Irish Volunteers and received a rifle at St. Lawrence’s Hotel in the course of the Howth Gun-running; marched in the party that was fired on by British soldiers at Bachelor’s Walk, Dublin; emig. to America with his wife on expiry of Kelly’s scholarship, 1914; stayed with an aunt in Pittsburgh; settled in New Canann, Connecticut to live and write, excepting a three-year period in Paris and Nice during 1930-33; issued anthology of 1916 poets; issued Wild Earth (1916, rep. 1950), poetry collection; wrote children’s stories for NY Sunday Tribune and issued a collection as issued King of Ireland’s Son (1916); commissioned by Hawain Legislature to collect folklore, published in three vols. for schoolchildren; The Grasshopper, a play adapted from Count Keyserling, with F. E. Washburn-Freund (NY 1917); |

| issued Three Plays (1917) containing The Fiddler’s House, The Land, and Thomas Muskerry; issued the novels Castle Conquer (1923),a novel; supplied his opinion on the Irish Censorhip to M. Lyster, a contributor to the Irish Stateman (Oct. 1928 identifying the result with ‘resentment and mockery’ leading to ‘an anti-clerical movement’ in Ireland (Oct. 1928); wrote Balloon (Agunquit, Maine, 1929), a play; moved to France and lived in Paris and Nice, 1930-33 - re-establishing acquaintance with James Joyce in this period; moved back to New York, where he occupied a flat overlooking Central Park from his first arrival, teaching occasionally at Columbia University, 1939; wrote The Show-Booth, a play adapted from Alexander Blok (Dublin 1948); he divided his time after 1957 between New York, and Woods Hole, Massachusetts, staying with his sister at Edenvale Road, Ranelagh, during occasional visits to Dublin; subsisted mainly on royalties from his children’s books and his wife’s income as a teacher and critic; |

| issued a second novel, The Flying Swans (1957) and a revised edition of Three Plays (1963); also plays as The Challengers: Monasterboice, Glendalough, and Cloughoaghter (Dublin 1966); he made his final visit to Ireland for launch of the Figgis [2nd] edn. of The Flying Swans (1967), which he regarded as his most accomplished prose work; d. Enfield, Connecticut, 11 Jan. 1972; bur. in Ireland in St. Fintan’s Cemetery, Sutton, with Mary Colum; some of his MSS are held in Berg Collection (NYPL). NCBE JMC IF DIL DIW DIH OCEL KUN HAM OCIL FDA |

[ top ] |

||||

| Plays | ||||

|

||||

| Collected plays, | ||||

|

||||

| Poetry | ||||

|

||||

|

||||

| Novels | ||||

|

||||

| [ top ] | ||||

| Fiction & Mythology | ||||

|

||||

| Collected & Selected Fiction | ||||

|

||||

| [ top ] | ||||

| Miscellaneous Prose | ||||

|

||||

|

||||

| Prefaces & Editions | ||||

|

||||

| Articles (Selected) | ||||

|

||||

| See also Padraic Colum, ‘Early Days of the Irish Theatre’, in Abbey Theatre: Interviews and Recollections, ed. E. H. Mikhail (London: Macmillan 1988), pp.59-71. | ||||

| [ top ] | ||||

Padraic Colum’s contributions the Dial during 1917-1929 [ The following list was supplied by Cathryn Setz via Facebook and Dropbox (21 Oct. 2014) ]

- ‘The Imagists’, in Dial lxii: 736 (22 Feb. 1917), p.3-.

- ‘The Celt and some Irishmen’, in Dial lxii: 742 (17 May 1917), p.435-.

- ‘Jacinto Benavente’, in Dial [vol?]: 752 (25 Oct., 1917), p.393-.

- ‘The swallows’, in Dial lxiv: 758 (17 January 1918), p.50-.

- ‘New Plays and a New Theory’, in Dial lxiv: 763 (28 March 1918), p.295-.

- ‘Folk Seers’, in Dial (Sept. 1920): 300-.

- ‘Autumn’, in Dial (June 1921), p.626-.

- ‘The Sad Sequel to Puss-in-Boots’, in Dial (July 1921), p.28-.

- ‘Mr Yeats’ Selected Poems’, in Dial (Oct. 1921), p.464-.

- ‘In a Far Land’, in Dial (Nov. 1921), p.550-.

- ‘Irish Fairy Tales’, in Dial (Nov. 1921), p.601-.

- ‘Half Enchantment’, in Dial (Dec. 1921), p.711-.

- ‘Sea and Sardinia’, in Dial (Feb. 1922), p.193-.

- ‘Memoirs of a Midget’, in Dial (April 1922), p.416-.

- ‘Lady Gregory’s Plays’, in Dial (Nov. 1922), p.572-.

- ‘The Lehua Trees’, in Dial (Dec. 1923), p.1-.

- ‘The South Seas Again’, in Dial (January 1924), p.81-.

- ‘A Note on Hawaiian Poetry’, in Dial (April 1924), p.336-.

- ‘Three Hawaiian Poems: The Pigeons on the Beach’, in Dial (April 1924), p.340-.

- ‘Desert Arabia’, in Dial (Oct. 1924), p.336-.

- ‘Queen Gormlai’, in Dial (May 1925), p.391-.

- ‘The Possessed’, in Dial (Feb. 1925), p.142-.

- ‘Lost Fatherlands’, in Dial (Jan/Jun [?] 1926), p.61-.

- ‘Asses’, in Dial (Sept. 1926), p.4-.

- ‘Aqueducts’, stratagems, and shows. Dial (Dec. 1926), p.511-.

- ‘The Herd’s House’, in Dial (Dec. 1926), p.471-.

- ‘From Circus to Theatre’, in Dial (Feb. 1927), p.157-.

- ‘Stendhal’, in Dial (June 1927), p.470-.

- ‘A Showman’, in Dial (August 1927), p.156-.

- ‘Camps and Museums’, in Dial (Sept. 1927), p.254-.

- ‘Archaeologist as Historian’, in Dial (Dec. 1927), p.519-.

- ‘Dublin Roads’, in Dial (Feb. 1928), p.122-.

- ‘The River Episode from James Joyce’s Uncompleted Work’, in Dial (April 1928), p.318-.

- ‘The Possessed Sea-Captain’, in Dial (June 1928), p.511-.

- ‘Etched in Moonlight’, in Dial (July 1928), p.69-.

- ‘From the Founding of the City’, in Dial (Nov. 1928), p.426-.

- ‘Mr. Weston’s Good Wine’, in Dial (Oct. 1928), p.350-.

- ‘Prologue to Balloon: a Comedy’, in Dial (Dec. 1928), p.490-.

- ‘Cicero and the Rhetoricians’, in Dial (January 1929), p.52-.

- ‘Spinoza and his Correspondents’, in Dial (Feb. 1929), p.142-.

- ‘The Theatre’, in Dial (Feb. 1929), p.169-.

- ‘Infinite Correspondences’, in Dial (March 1929), p.8-.

- ‘The Theatre. Dial (April 1929), p.349-.

- ‘Actualities and Potentialities’, in Dial (May 1929), p.428-.

- ‘The Theatre’, in Dial (May 1929), p.440-.

- ‘Studies in Personality’, in Dial (June 1929), p.4-.

- ‘The Theatre’, in Dial (June 1929), p.531-.

- ‘The Journey’, in Dial (June 1929), p.12-.

Padraic Colum’s The King of Ireland’s Son is available at Gutenberg Project - online.

Padraic Colum, ed., An Anthology of Irish Poetry (1922) is given in Bartleby Quotations - as attached, or online.

[ top ]

Bibliographical details

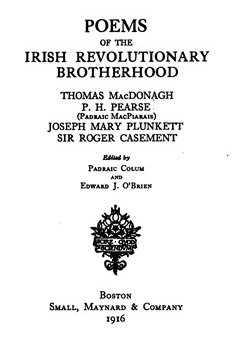

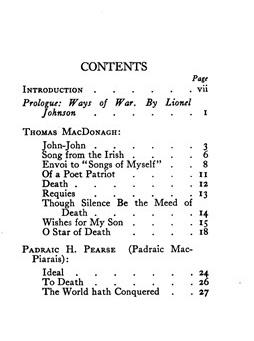

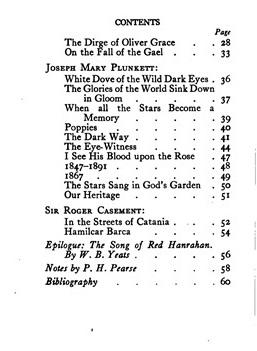

Anthology of Irish Verse, ed. Padraic Colum (NY: Boni & Liveright 1922; rev. edn. 1948) contains 181 classic Irish poems. (See Contents - as attached; also, an extract from the Introduction, as infra.)Poems of the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood, ed. by Padraic Colum & Edward J[oseph Harrington] O’Brien (Boston: Small, Maynard & Company 1916), xxiv, 60pp. [Intro. vii-xxiv; Notes, 58ff; ends with Yeats’s “Song of Red Hanrahan”, pp.56-57; see extracts.]

Poems of the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood

ed. by Padraic Colum and Edward J[oseph Harrington] O’Brien

Contributors: Joseph Mary Plunkett, Padraig H. Pearse, Joseph Mary Plunkett, Sir Roger Casement

Published: 1916, Small, Maynard & Company (Boston)

Pagination: xxiv + 60 [Notes, 58ff.]

Available at Internet ArchiveC

L

A

R

E

L

I

B[ Copy held in Harvard College Library ] A Treasury of Irish Folklore: The Stories, Traditions, Legends, Humours, Wisdom, Ballads and Songs of the Irish People, ed. with intro. by Patrick Colum, 2nd rev. edn. (NY: Crown Pub. 1967), 613pp, comprised of 9 parts: “The Irish Edge”; “Heroes of Old”; “Great Chiefs and Uncrowned Kings”; “Ireland Without Leaders”; “Ways and Traditions”; “Fireside Tales”; “The Face of the Land”; “Ballads and Songs”; “A Bit of the North” [sect. incls. John Hewitt’s “Once Alien Here”, poem with “Winter” by James Orr and collected by Hewitt in Rann (Winter 1950), p.6]; also num. biographical articles from The Gael, viz., Geraldine M. Haverty, “Lord Edward F.” (Sept. 1901), pp.293-296; Charles O’Hanlon, “John Philipot Curran,” Gael (Feb. 1900), pp.52-54; Douglas Hyde, “A Famous Mayo Poet [Raftery]”, in The Gael (April 1903), pp.115-16. Note that the Abbé Edgeworth is quoted at p.248. (See separate copy in RICORSO Bibliography > Anthologies via index or direct [sep. window].

Irish Elegies: Memorabilia of Roger Casement, Thomas MacDonagh, Kuno Meyer, John Butler Yeats, Arthur Griffith, Michael Collins, Thomas Hughes Kelly, Dudley Digges, James Joyce, William Butler Yeats, Monsignor Padraig de Brun, Seumas O’Sullivan / by Padraic Colum [Dolmen Chapbook, 9](Dublin: Dolmen Press 1958), 11, [1]pp. [24.5 cm.]; Do. [with 3 add. poems, viz., Allen, Larkin & O’Brien] (Dublin: Dolmen Press 1961; 3rd edn. 1963), 19, [5]pp. [actually March 1962]; and Do. [4th edn.] (Dublin: Dolmen Press; [US distrib., Humanities Press] 1976), 32pp. [22cm]. A 2pp. “Prospectus” was issued in June 1958.

Anna Livia Plurabelle, by James Joyce with a Preface by Padraic Colum (1928), pp.vii-xix [prev. ‘River Episode from James Joyce’s Uncompleted Work’, in Diala, April 1928, pp.318-22; also printed in Our Friend James Joyce (1958), pp.139-43; extract in Robert Deming, ed., James Joyce: The Critical Heritage (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul 1970) [Vol. 2], pp.388.

[ top ]

Criticism

|

| See also |

|

[ top ]

Commentary

W. B. Yeats: Yeats once criticised the characters in Colum’s plays in ‘[they] were not the true folk. They are the peasant as he is being transformed by modern life. [...]’. Further, Yeats writes of his language: ‘[It is the speech of the people] who think in English, and ... shows the influence of the newspaper and the national schools.’ (Yeats, Explorations, Macmillan 1962, p.183; quoted in Loreto Todd, The Language of Irish Literature, Gill & Macmillan 1989, p. 168.)

W. B. Yeats wrote of Colum that ‘He has read a great deal, especially of dramatic literature, and is I think , a man of genius in the first dark gropings of thought.’ (Quoted in Sanford Sternlicht, ‘Padraic Colum’, in Alexander Gonzalez, ed., Modern Irish Writers: A Bio-Critical Sourcebook, NY: Greenwood 1998; see further below.)

John B. Yeats: ‘The Colums I see sometimes. I don’t know what the Devil he means by admiring the Germans. He does not really admire them, only tries to do so. Meantime the tide here aainst the Germans everywhere is setting in with greater and greater strength. It is like wathcing the first movement of heaped up snow in the Alps knowing that it will soon be an avalanche. More and more all eyes are turned to Roosevelt. [...]’ (Letter of 7 April, 1916; 317 W 29, NY; printed in Declan J. Foley, ed. & intro., The Only Art: Jack B. Yeats - Letters from his Father John Butler Yeats; Essays on Their Works, Dublin: Lilliput Press 2008, p.113.) Further: ‘Colum asked me to tea on Saturday’s and I had a good excuse, and so excaped - possibly again Kuno Meyer. Long ago I liked Kuno Meyer, but never sure of his strict honesty and veracity. He wants to be so agreeable to everyone [...] a man of that kind you never know. [... &c.]’ (31 May 1916; in idem. p.114.)

James Joyce: In his Pola Notebook, Joyce wrote: ‘That queer thing - genius.’, being ‘Æ’s [George Russell] term for Colum, which led Joyce to call Colum ‘the Messenger-boy genius’, reflecting his occupation in the Post Office. (See Kain & Scholes, The Workshop of Daedalus, [... &c.] Northwestern UP 1965, p.84.)

James Joyce - Joyce wrote to his brother Stanislaus: ‘I read in the D.M. under the heading “Riot in a Dublin theatre” that a “clerk” named Patrick Columb and someone else were put up at the Police Courts for disorderly conduct in the Abbey Theatre at a performance of Synge’s new play The Playboy of the Western World. [...] Columb must either have been forsaken by Kelly or have returned to his office since he is called a clerk.’ (Selected Letters, ed. Richard Ellmann, Faber 1975, p.143-44.) Note: Ellmann explains in a footnote that Joyce mistook the father of the writer for his son. [For a longer extract see under Joyce > Quotations - infra.]

Ernest Boyd regarded Colum and Seamus O’Sullivan [Starkey] as the ‘promising successors of Yeats’. (Ireland’s Literary Renaissance, NY: Knopf, 1922, pp.255-58).

|

John Hewitt, review-essay on The Poet’s Circuits (OUP [1960]), in Threshold, ed. Mary O’Malley & Hewitt, Vol. 4, No. 2 [Padraic Colum Special Issue] (Autumn/Winter 1960), calls it ‘the most acceptable book of verse by an Irish poet to have come out since the War ... it contains the bulk of Colum’s poems which have Irish subjects (pp.61-67.) Further: ‘For decades I have found, line after line, stanza after stanza, of Colum’s memorable, life-enhancing, and have therefore felt sure of their high quality.’ (op. cit., p.66). ]

D. E. S. Maxwell, A Critical History of Modern Irish Drama 1891-1980 1980 (Cambridge UP 1984; 1985), notes that ’[i]n its 1963 publication, Thomas Muskerry is quite extensively revised ... introduc[ing] a new character, it brings on stage another only mentioned in the 1907 [sic] text, and compresses the final scene’; ‘the changes ... do not improve the plays original statement of Muskerry’s decline and the back-biting small-town life which surrounds it.’ (Maxwell, op. cit., 1985, p.70.) Maxwell remarks of the playwright William Boyle that he ‘did not move, in phrases from a defence by Colum of Thomas Muskerry, into the “universal”, the “typically human”, from intimate knowledge of “his own locality”.’ (vening Telegraph, 20 May 1911; Maxwell, op. cit. p.72.)

Maurice Beja, James Joyce: A Literary Life (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1992), on Sylvia Beach’s contractual claims on Ulysses: ‘The next year, 1931, decisions about what she would be recompensed if another edition were published had to be faced: her demand turned out to be the immense sum, for the time, of $25,000. No one could deny, then or now, that she full deserved even such a high figure [...] nevertheless, no publisher could have agreed to such a demand, and matters stalled for a time. Finally Padraic Colum acted as intermediary, making periodic visits to Shakespeare and Company on Joyce’s behalf; one day he asked her what rights she had in Ulysses, and she mentioned that after all there was her contract. When he doubted its existence and she showed it to him, he at last blurted out the message that, she later said, “immediately floored me”: “You are standing in Joyce’s way!” As soon as he left, Beach telephoned Joyce and in cool anger told him that she would make “no further claims” on Ulysses. In fact, however, she did obtain royalties for some editions, and Joyce had also presented her, in gratitude, with the manuscript of Stephen Hero.’ (p.95.) Note that she sold Stephen Hero to Buffalo University, where it was edited by Theodore Spencer and published in 1944.

Seamus Deane, Short History of Irish Literature (1986), p.160 [re. Abbey], ‘blend of folk drama and basic Ibsen [established by Thomas Muskerry (1910) and plays by T. C. Murray (1910) and George Fitzmaurice (1907)]’.

David Cairns & Shaun Richards, Writing Ireland: Colonialism, Nationalism and Culture (Manchester UP 1988), remarks: ‘Colum’s The Saxon Shillin’ had been found too contentious by the Fay’s Irish national Dramatic Society because of its overt propagandising in which a family’s eviction is resisted by the son who, having once taken ‘the Saxon shilling’’ and joined the British Army comes to see that his loyalty is with the family in whose defence he dies. Produced by the children’s dramatic class of Inghinidhe na hÉireann in 1903, Colum’s basic theme of British authority and asserting Irish rights to land and property, even at the pain of individual loss [...]’ [76]

Sanford Sternlicht: ‘Unlike Yeats, Colum never groped deeply in thought. He was content to feel deeply about his country, his wife, his friends, and the poor, hardworking people of the rural Ireland of his youth.’ (Sternlicht, ‘Padraic Colum’, in Modern Irish Writers: A Bio-Critical Sourcebook, ed. Alexander Gonzalez, NY: Greenwood 1998, p.55.)

R. F. Foster, W . B. Yeats: A Life - I: “The Apprentice Mage” (OUP 1997) - of the Irish Literary Theatre: ‘Padraic Colum noted acidly that Reading Committee meetings were held in Gregory’s sitting-room at the Nassau Hotel [from the Royal Hibernian Hotel] because WBY [288] suggested it would be warmer; the centre of decision-making thus shifted to her sphere.’ (pp.288-89.)

[ top ]

| See “A Selection of the Poems of Padraic Colum” - as attached. |

| “An Old Woman of the Roads” | |

|

I could be quiet there at night Och! but I’m weary of mist and dark, And I am praying to God on high, |

| Note possible inspiration in Alice Milligan [q.v.]: ‘[...] And I am praying to God on high, / And I am praying Him, night and day, / For a little house, a house of my own, / Out of the wind and the rain’s way.’ (Quoted in Benedict Kiely, Sing to the Bird, London: Methuen 1991, p.129.) | |

[ top ]

| “She moved through the Fair”: | |

|

And then she went homeward The people are saying |

| —Quoted in Frank Gallagher, Days of Fear (NY & London: Harper Bros. 1929]), 144-45. Note that Gallagher correctly identifies it as a poem by Colum whereas it is often mistaken for a traditional ballad. The song is sung by a young Republican prisoner during a hunger-strike concert in 1920. Gallagher writes: | |

|

|

[ top ]

| “The Poor Girl’s Meditation” | |

|

Love takes the place of hate, And, O young lad that I love, |

| Rep. n Patrick Crotty, ed., The Penguin Book of Irish Poetry (2010). See Patricia Craig, reviewing same in The Independent [UK] (8 Oct. 2010), remarking that it is not, as implied therein, an autograph poem but in fact a close translation of the Irish original, ‘Tá me ’mo shuidhe o d’eirigh an ghealach areir’. | |

[ top ]

“Poor Scholar of the 1840s”: ‘And what to me is Gael or Gall? / Less than the Latin or the Greek / I teach these by the dim rush light / In smoky cabins night and week. / But what avail my teaching slight? / Years hence, in rustic speech, a phrase, / As in wild earth a Grecian vase!’ (Quoted in Benedict Kiely, Drink to the Bird, London: Methuen 1991, p.15; ee also Kiely’s remarks on MacDonagh and Colum’s decision about the name of the collection Wild Earth (idem.)

| “A Poor Scholar of the 1840s” | |

|

“You teach Greek verbs and Latin nouns,” And what to me is Gael or Gall? |

| Bibl. note: Quoted [in part] in P. J. Dowling, The Hedge Schools of Ireland 1935; rep. 1968); cited in Tessa Maginess [QUB], ‘Hedging Hegemony: From Salubrious Scriptorium to the Sunny Side of a Ditch’, supplied by the author, Feb. 2014; full text available at Poem Hunter - online; accessed 28.04.2022. | |

[Note that the poem’s title is playfully echoed in Seamus Heaney’s “A Settle-bed in the 1940s” - as attached. ] |

|

[ top ]

| Poems of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, ed. & intro. by Padraic Colum (1916) | ||

|

|

|

| Introduction | ||

|

||

| See full-text copy of Introduction - as attached. | ||

| Anthology of Irish Verse, ed. Colum (NY: Boni & Liveright 1922; rev. edn. 1948), Introduction: |

|

| —See full-text copy in RICORSO Library, “Critical Classics”, Anglo-Irish [as attached]. |

[ top ]

On good poetry: ‘words as simple and as clear / As raindrops off the thatch.’ (The Poet’s Circuits: Collected Poems of Ireland, OUP 1960; quoted in Zack Bowen, Journal of Irish Literature II, 3, 1973, with remarks identifying the quality described with Colum’s own verse-manner .)

Joyce’s New Work [review of Finnegans Wake], in New York Times (7 May 1939), “Book Review”: ‘[...] Language, nothing less than the problem of conveying meaning through words, is the first term we have to discuss in connection with Finnegans Wake. Let us get away from the book for a moment and begin by saying that writing today - I mean what can be described as imaginative writing - is dissociated from the value-making word: that is, it is writing, passing from the brain through the hand to the paper without ever coming out on the lips to be words that a man would say in passion or merriment. I am not speaking now of magazine writing, but of the writing of authors of status - John Galsworthy, for instance. As I write this sentence I see the title of a moving picture before me: it is The Lone Ranger; I think that there is more verbal creation in these words than in chapters of Galsworthy’s. ‘Ranger’ is a real word, holding a sense of distance, suggesting mountains; ‘lone’ beside it makes the distance inner. There are great writers today who do not put us off with destitute words: Yeats’s ‘The dolphin-torn, the gong-tormented sea’ are value-making words. / The problem of the writer of today is to possess real words, not ectoplasmic words, and to know how to order them. They must move for him like pigeons in flight that make a shadow on the grass, not like corn popping. And so all serious writers of English today look to James Joyce, who has proved himself the most learned, the most subtle, the most thorough-going exponent of the value-making word. [...]’ (See full text in RICORSO Library, “Criticism / Major Authors” - James Joyce, infra.; and see also various comments in James Joyce, Commentary, infra.)

‘Life in the World of Writers’ [interview], in Hickey & Smith, eds., A Paler Shade of Green (1972), pp.13-22: ‘The most fruitful and exciting time in the Irish Dramatic Movement was before it became the Abbey Theatre. You must remembers that the Abbey Theatre was given to Yeats by Elizabeth Horniman, but she had a wrong idea of Ireland altogether. She thought the Gaelic League would murder her. I remember the opening ... with the production of Yeats’s On Baile’s Strand on 27th December 1904. The élite of Dublin was there, both nationalist and Unionist. But then came the withdrawal from the Abbey .... Yeats ... continued to create himself. One of the ways in which he achieved this was through the theatre .... He speaks of trying to find a more manly energy. He found that energy in the theatre; but it was a deliberate choice. Although not by nature a dramatist, he wrote the best dramatic verse since the Jacobeans, since Webster. I think Yeats was very sincere about Ireland. Later he adopted what might be termed the Ascendancy point of view. He admired the Ireland of Grattan and Berkeley and the great Anglo-Irish writers.’ (p.17).

Cont. (‘Life in the World of Writers’, 1972): ‘There was more of our traditional poetry in the peasant life of Synge’s plays than in the life of O’Casey’s Dublin workmen. O’Casey’s dialect never appeared to me to be real. It was Dublin speech, and I didn’t quite accept it. He was not really influence by what is called the Irish Movement. Writers like Yeats and Synge and myself were influenced by the ideas of the Movement - the language movement and so on, but O’Casey is the successor to Boucicault.’ (Hickey & Smith, op. cit., p.19).

‘Whereas Joyce came from a nationalistic family, I don’t think Beckett did. He did not have the same attachment to Ireland. It was not the same heartbreaking disruption on his part to leave the country as it was for Joyce. / The Beckett I knew in Paris was a very silent and I think a troubled man. He was misled about the withdrawl of The Drums of Father Ned from Dublin Theatre Festival 1958. This was a great misunderstanding on Beckett’s part. O’Casey had the curious idea that he was being accused of anti-clericalism and that the bishops and everybody here were against him. There were to be religious services to start the Festival: a Mass, a Church of Ireland service, even a Jewish service. It was all nonsense to start like that. The Catholic Archbishop of Dublin very properly decided he wouldn’t say the Mass. That was all there was too it. But it was blow up into an imaginary anti-O’Casey crusade led b the Archbishop and it was taken in New York that O’Casey was being persecuted. It wasn’t like that at all. But Beckett was misled by the news. He withdrew his mime plays and said he would not return to Dublin. [...] In breaking new ground, Godot is a work of genius, but I feel Beckett has reached a dead end and that his theatre cannot be developed further.’ (Hickey & Smith, op. cit., p.20).

Colum further speaks of plays ‘in the convention of the Japanese Noh theatre ... using Irish subjects’ and refers to the plays Moytura [on William Wilde]; Glendalough [on Parnell]; Monasterboice [on G. M. Hopkins]; Clogher [on Roger Casement] and Kilmore [on Bishop Bedell] (Hickey & Smith, op. cit., p.21).

Hiberno-English: ‘Yeats, Lady Gregory, Synge, and all were doing it, but the truth of the matter is that I was the only one of the lot that knew what the real country speech sounded like. I wouldn’t want to say a word against Synge’s language, which is exquisite, very fine, but has no more to do with how people actually spoke than Oscar Wilde’s dialogue in his comedies has to do with how people spoke in London drawing rooms in the eighteen-nineties.’ Further: ‘Anything I have written, whether in verse or narrative, goes back to my first literary discipline, the discipline of the theatre.’ (RTÉ interview; q. source.)

[ top ]

|

[ top ]

Stay on the land!: ‘Aren’t they foolish to be going away like that, Father, and we at the mouth of the good times? The men will be coming in soon, and you might say a few words ... you might say, “Stay on the land and you’ll be saved body and soul; you’ll be saved in the man and in the nation ...”. Do you ever think of the Irish nation that is waiting all this time to be born?’ (Cornelius, in The Land; cited in Shaun Richards, ‘Progressive Regression in Contemporary Irish Culture’, [Pt. 3 of] ‘The Triple Play of Irish History’, in Irish Review, Winter-Spring 1997, p.37.)

‘National freedom is a concept that varies in different countries and covers many different sentiments. For Irish people it means a reconquest. It is a reconquest by stages, each stage leaving an emotional deposit: survival as Irish through the outlawry of the Penal days, Catholic Emancipation, destruction of feudalism thorugh the agrarian struggle, the attainment of national consciousness through the Gaelic League and Sinn Féin ... The men and women of Dail Eireann, whether they voted or the Treaty or against it, had in their bones a history that [an Englishman] could never know: their grandfathers had heard for the first time in a hundred yards a bell ring from a Catholic place of worship.’ (Story of Arthur Griffith; quoted in Julian Moynahan, Anglo-Irish: The Literary Imagination of a Hypenated Culture, 1995, with comment: Colum ... cannot help sounding this note of native triumph ...’, p.10.)

The 1916 Leaders: ‘An Irishman knows well how those who met their deaths will be regarded. They shall be remembered for ever; they shall be speaking for ever; the people shall hear them for ever.’ (Introduction, Poems of the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood, Boston 1916; echoing Yeats’s Kathleen Ni Houlihan.)

W. B. Yeats: Colum wrote an obituary-cum-review of Yeats’s Autobiographies in Book Review (12 Feb. 1939), giving due acknowledgement to the Fay brothers’ role in the Irish National Theatre and summarising the question of Yeats’s Irishness in these terms: ‘[Yeats was] a Byzantine one, like el Greco, strayed into the western world, and expressing in our time that unaccountable affinity that the Ireland of the ninth and tenth century had for Byzantine civilisation.’ (Cited in Roy Foster, ‘When the Newspapers have forgotten me ...’, in Warwick Gould & Edna Longley, eds., Yeats Annual 12, London: Macmillan 1996; offprint supplied by author.)

[ top ]

References

Stephen Brown, Ireland in Fiction (Dublin: Maunsel 1919), gives bio-data: b. Longford, taught at St. Enda’s School; emig. to USA in 1914; lists Broken Soil (1903); The Land (1905), and Thomas Muskerry (1910), plays that established the realist pattern at the Abbey. Also Collected Poems (1932); employed to record Hawaiian legends, 1924, resulting in [At] The Gateways [of] the Day, 1924, and The Bright Island (1925); The Legend of St. Columba; The Story of Lowery Maen (1937), a narrative poem; also Ten Poems (1959); Our Friend James Joyce, with Mary Colum (1959); The Poet’s Circuits (1960); Wild Earth; Dramatic Legends, etc. Travel, criticism and biography incl. A Half Day’s Ride, Corsica (1932); Ourselves Alone, The Story of Arthur Griffith & the Origin of the Irish Free State (1959).

D. E. S. Maxwell, A Critical History of Modern Irish Drama 1891-1980 1980 (Cambridge UP 1984; 1985), lists Three Plays, The Land, The Fiddler’s House, Thomas Muskerry [performed 1907] (Dublin: Allen Figgis, 1963, rev. edn.); also The Land (Dublin: Maunsel 1905); The Fiddler’s House (1907); Thomas Muskerry (1910). Cites study by Zack Bowen as Padraic Colum (1970) and another in Journal of Irish Literature, 2 Jan. 1973 (Proscenium 1973). Note that chronology in the front pages of Maxwell (1985) gives 1910 as the date of Thomas Muskerry, and thus also the bibliography.

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Literature (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 2, selects The Land [655-59]; The Poet’s Circuits [763-64]; “Across the Door”, “Cradle Song” [763], “Woman by the Hearth” [763-64], “Old Woman of the Roads”, “Poor Scholar” [764]; Wild Earth and Other Poems [764-65], “She Moved Through the Fair” [764-65], “Drover” [765], “I Shall not Die for Thee” [765]; 780; 781, 1012, 1026, 1219; 781, BIOG: five years as railway clerk in Dublin; scholarship; founded The Irish Review with Thomas MacDonagh and James Stephens; emigrated with Mary, 1914; three years in France, 1930-33; taught Columbia Univ.; d. Enfield, Connecticut. [Criticism as above.]

Alexander G. Gonzalez, ed., Short Stories form the Irish Renaissance, An Anthology (Whitston 1993), contains three of his stories including “Three Men”, a vinegary portrait of small town intellectual life.

[ top ]

Library Catalogues

Berg Collection of the New York Public Library holds ten book-titles by Colm together with c. 15 other papers incl. three typescript fragments of The Flying Swans, an essay on Carl Sandberg and a writing on Arthur Griffith (dated 21 Jan. 1950), all collected by W. T. Levy along with literary works of Robinson Jeffers, et al.British Library holds Goldsmith, selected with intro. [1913, 1928]; ed. Griffin’s Collegians (1918); Adventures of Odysseus, and Tale of Troy (1920 [1st edn. recte 1918]); pref. to Joyce’s Anna Livia Plurabelle (1928); Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination, intro. (1908); Gulliver’s Travels, ed. (1919); Songs and Poems of George Sigerson, with an introduction by Padraic Colum (Dublin: Duffy & Co. 1927), vi, 72pp.; The Big Tree, stories of my own countryside, ill. Jack B. Yeats (NY 1935); Broadsheet Ballads [being a Collection of Irish Popular Songs (Maunsel 1913); The Fiddler’s House (1907); Three Plays [contains Fiddler’s House, The Land, and Thomas Muskerry] (1917); The Land (1905); Half Day’s Ride, or Estates of [?recte in] Corsica (London 1932); Legend of St. Columba (1936); My Irish Year (Mills & Boon, London 1912); The Road Round Ireland (DIL NY 1926); Legends of Hawaii [include sel. from [At] The Gateway of the Day (New Haven. Conn., 1924), and The Bright Islands (New Haven 1925); A Boy in Eirinn ([1913] Oifig Díolta Foillseacáin Ríaltais, 1934). Note that the BL holds no copies of Balloon, Bearkeeper, or Grasshopper.

Belfast Central Library holds 12 titles, incl. Padraic Colum, Ziehende Schwune, roman [The Flying Swans] (Hamburg: Kroger 1960), 658pp.

Booksellers’ Catalogues

Whelan Books, No. 32 lists Half a Day’s Ride; or, Estates in [sic] Corsica [1st ed.] (Macmillan 1932); joint edition of The Land and The Fiddler’s House [n.d.] Cathach Books Catalogue, No. 12 (1996-97) lists also The Children of Odin (London 1922), ill. Willie Pogany; also The Fiddler’s House; A Play in Three Acts and The Hand: An Agrarian Comedy (Dublin: Maunsel 1909) [sic], fp. port. The Road Round Ireland (NY: Macmillan 1930), 492pp., ill. Three Geese Catalogue (1999) lists Irish Fairy Tales (1920), ill. Arthur Rackham; another edn. with ills. (1953).

[ top ]

Notes

George [“Æ”] Russell (1) - letter to Sarah Purser of 5 March 1902: ‘[...] I have discovered a new Irish genius – his name is Columb [sic]: only just twenty, born an agricultural labourer’s son, laboured himself, came to Dublin two years ago and educated himself, writes astonishingly [39] well, poems and dramas with real originality. He has three or four more years at his back he will be a force and I believe a name - He is a rough jewel at present, but a real one. I prophecy about him.’ (Alan Denson, ed., Letters from AE, London: Abelard-Schuman 1961, pp.39-40.) [See also under Monk Gibbon, infra.]

W. B. Yeats called Padraic Colum ‘the one victim of [George] Russell’s misunderstanding of life that I rage over’. (Quoted in Frank Tuohy, Yeats: An Illustrated Biography, London: Macmillan 1976, p.135; (See further under Russell, Commentary - infra.)

James Joyce (1): Colum joined Joyce in George Robert’s office when the former was urging the publication of Dubliners and unhelpfully called “Encounter” - which he read on the spot - ‘a terrible story’. He also also posed a facetious question, asking were the stories were all about public houses. (See Richard Ellmann, James Joyce, 1965, p.340.)

James Joyce (2) - see Herbert Gorman, James Joyce: His First Forty Years [NY 1924] (London: Geoffrey Bles 1926): ‘[...] when we find Mr. James Joyce remarking to Yeats, “We have met too late; you are too old to be influenced by me,” [Note: ‘This statement and several of the following facts are taken from Padraic Colum’s excellent article ...], &c.’ (p.5; see further under Joyce, Commentary, Gorman, infra.)

James Joyce (3): In a notebook of 1904, Joyce entered a remark which he had heard in Dublin: ‘Miss Esposito, I never see a rose but I think of you’ (Herbert Gorman, James Joyce, NY 1939, p.135). Richard Ellmann identifies Colm as the author of the remark a footnote to Selected Letters of James Joyce (1975) - viz., the letter of 19 Aug. 1906 where Joyce wrote irreverently that W. B. Yeats ‘should hurry up and marry Lady Gregory - to kill talk’, and that ‘Colm ought to propose to his roselike Miss Esposito.’ (Ellmann, op. cit., 1975, p.9.)

Monk Gibbon: Gibbon writes of George Russell’s fostering of Irish poets: ‘James Joyce was one of his beneficiaries. But the three who meant most to him were Colum, Stephens and Starkey (Seumas O’Sullivan). “I have discovered a new Irish genius - Columb: only just twenty, born an agricultural labourer’s son [...; Gibbons lacunae; see George Russell’s original, as supra]. When he has three or four more years at his back he will be a force and I believe a name.” Three years later: “Colum’s poems rude as they are reveal a talent which I think one day Europe will recognise.” And, thirty years later, writing to Colum himself, “You are always kind. You are as good as you were when you were young, which is saying a great deal about anybody.” Almost another thirty years have passed since that was said, but to those of us who know Colum today the words are as true as ever.’ (Foreword to Letters from AE, ed. Alan Denson, London: Abelard Schuman 1961, p.ix.)

Note: Gibbon seems to imply by his preceeding paragraph that Joyce borrowed five pounds on a promise of returning it on the following day. See also Richard Ellmann, James Joyce (1959; 1965 edn.), quoting Russell: ‘Colum will be our our principal literary figure in ten years.’ (p.140.)

[ top ]

A. N. Jeffares, W. B. Yeats: A New Biography (London: Hutchinson 1988), writes: ‘When Maud Gonne vetoed Lady Gregory play Twenty-Five, as encouraging emigration, Colum’s Saxon Shillin’ was rehearsed instead; but Willie Fay, who shared the desires of Yeats, Lady Gregory and Synge for a professionally run national theatre, revised it into a form more suitable for staging; this led to accusations that Far was trying to avoid upsetting Dublin Castle ... Colum withdrew his play and Lady Gregory revised hers.’ (p.136).

D. George Boyce, Nationalism in Ireland (London: Routledge 1982; new edn. 1991), comments on Colum’s connection with the tap-root of Irish rural sentiment and refers to the ‘Kickham/Colum school whose popularity and influence lay in its depicting a way of life that people wanted to regard as authentic and truthful’ and with which they felt ‘at home’ (p.253); includes reference to R. J. Loftus, Nationalism and Anglo-Irish Poetry (1964), Chap. 7.

Con Markievicz: ‘In 1906 she rented a cottage in Ballally in the Dublin Mts. and came across back numbers of The Peasant and Sinn Féin, left by the previous tenant, Padraic Colum [thus] her interest in her country’s struggle for freedom was first aroused.’ (See Harry Boylan, Dictionary of National Biography, Gill & Macmillan 1988 > ‘Con Markievicz’.)

Top of the pops: ‘Colum, that most Celticky-Twilighty of figures, lived to savour “Ride a White Swan” at number one in the Hit Parade - how up-to-date does Mr. Crotty want?’ (Patrick Ramsay, review of Patrick Crotty, Contemporary Irish Poetry, 1995; in Fortnight, Jan. 1996, p.33.)

Thomas F.? Thomas Hughes Kelly, given as Thomas F. Kelly, in Richard Ellmann, James Joyce (1965 Edn., p.146.). Joyce walked 14 miles to Kelly’s home in Celbridge, Dec. 10, 1903, only to be refused admission by the porter, later receiving an apology by telegram though without offering anything on the grounds that he could not presently find £2,000 (as reported in ibid.).

Patrick Colum, father of Padraic, participated prominently in the so-called ‘Playboy Riot’ against Synge’s piece at the Abbey (The Playboy of the Western World, 1907), and charged with disorderly conduct and fined 40s. in a police court.

Francis Carlin, an Ulster regional poet and author of a memorable ballad on Count O’Hanlon, was discovered in New Yorker by Padraic and Mary Colum and found work in ‘the framework or firmament of Macey’s’ (see Benedict Kiely, Drink to the Bird, London: Methuen 1991, p.127.)

Portraits: there is a portrait of Colum by Robert Gregory in black crayon by, purchased by National Gallery of Ireland and held in Lady Gregory Collection [NGI]; also a pastel port. by Lily Williams [Abbey theatre]; and pencil drawing by John Butler Yeats [Abbey] and an oil portrait by John B. Yeats, 1903 (Sligo Library Collection). There is a portrait by Estelle Solomons 1921 (see Hilary Pyle, Estelle Solomons: Patriot Portraits, 1966).

Scheme: there is a letter from Charles J. Haughey to Sybil Le Brocquy referring to the making public of a scheme presumably for his welfare at the time of Colum’s illness in 30th July 1970. (See under Sybil Le Brocquy, Notes - Correspondence, infra.)

[ top ]