Life

| 1944- [fam. “Jack”]; ed. QUB; grad. with a general degree in zoology, histOry, social anthropology, philosophy and English; afterwards completed a doctorate on “Separation and Return in the Fiction of Brian Moore, Michael McLaverty and Benedict Kiely” (University of Oregon 1970), 1970; Ass. Prof. of English, University of British Columbia, Vancouver (later full professor); critical works include Forces and Themes in Ulster Fiction (1974); Fictions of the Irish Literary Revival (1987); Foster urged the acceptance of Hiberno-English as a literary language and later the attempt to establish dialectic status for Scotch-Irish (‘Ullans’) as distinct from Hiberno-English; |

| issued and Colonial Consequences (Dublin: Lilliput 1991), a broad-ranging study of Anglo-Irish literature since the seventeenth century combining various essays published elsewhere and including an up-dated view of Seamus Heaney; debated Northern Ireland with Gerry Adams at Board of Trade forum in Vancouver, 1994, and ed. with W. B. Smith The Idea of the Union: Statements [...] in Support of the Union (1995), publ. by the Belcouver Press - formed for the purpose; issued The Titanic Complex: A Cultural Manifest (1997); |

| ed., with C. G. Chesney, Nature in Ireland (1997); issued Recoveries (2002), a study of neglected strands in Irish cultural history incl. signally Darwinism and its opponents; ed. Cambridge Companion to the Irish Novel (2006); issued Irish Novels 1890-1940: New Bearings in Culture and Fiction (2008), correcting the ‘critical squint began with the Revival’ that resulted in the occlusion of much Irish writing; retired from Columbia, Vancouver and appt. to research chair at QUB, 2009; settled in Portaferry with his wife Gale Malmo; issued Between Shadows: Modern Irish Writing and Culture (2009), ‘‘a sequel of sorts to Colonial Consequences’; his dramatic monologue A Better Boy (2014) was performed by Ian MacElhinney at RBS London. FDA |

[ top ]

Works| Critical studies |

|

| Edited collections |

|

| Num. articles incl. |

|

|

[ top ]

Bibliographical details

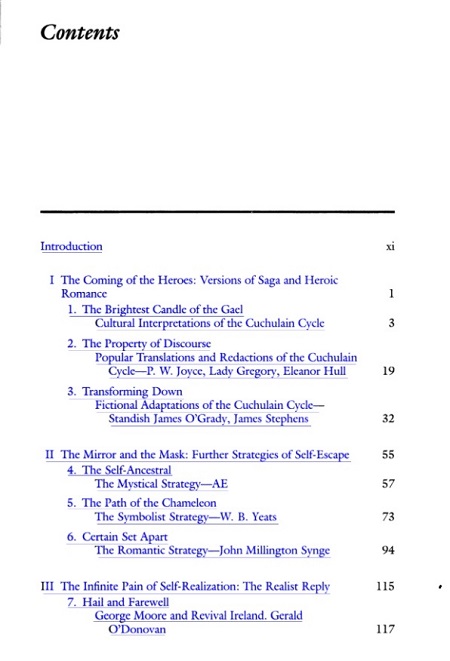

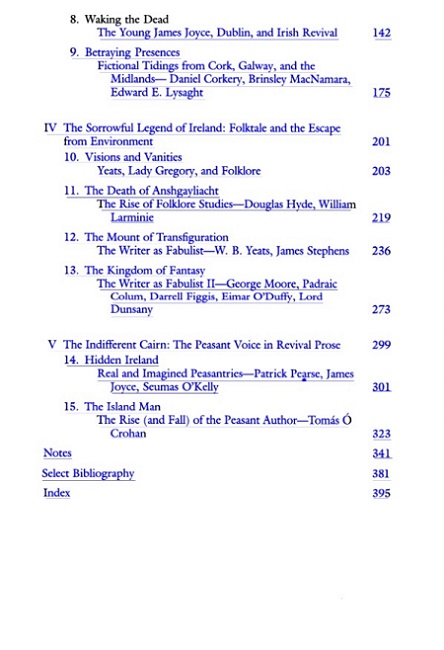

Fictions of the Irish Literary Revival: A Changeling Art (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1987) E.g., -

Remarks on The Charwoman’s Daughter (1912) and The Crock of Gold of James Stephens (both 1912) - 236 238 242 244 246 249 251 252 254 256 258 263 264 266 268 270 272 - [ From ‘Mount of Transfiguration: The Writer as Fabulist’ [IV:12] - available at Google Books online;

accessed 25.09.2020; copy as attached. ]Bibliographical details

Colonial Consequences: Essays in Irish Literature and Culture(Dublin: Lilliput Press 1991), 298pp. CONTENTS: Introduction; 1. The topographical tradition in Anglo-Irish poetry. 2. The geography of Irish fiction. 3. Irish modernism. 4. Post-war Ulster poetry: the English connection. 5. The poetry of Seamus Heaney. 6. The poetry of Patrick Kavanagh. 7. "The dissidence of dissent": John Hewitt and W.R. Rodgers. 8. Yeats and the Easter Rising. 9. The landscape of three Irelands: Hewitt, Murphy and Montague.; 10. Heaney’s redress. 11. A complex fate: the Irishness of Denis Donoghue. 12. The critical condition of Ulster. 13. New realism: a future for Irish studies. 14. Who are the Irish?. 15. Culture and colonization: view from the north. 16. Radical regionalism. [Excerpts to be found in Ricorso under Heaney, Hewitt, Yeats .. et al.]Nature in Ireland: A Scientific and Cultural History, with Helena C. G. Chesney [assoc. ed.] (Dublin: Lilliput Press 1997), xii, 658pp. List of Illustrations [vii]; Preface [ix]; CONTENTS: John Feehan, ‘The Heritage of the Rock’ [3]; John Wilson Foster, ‘Encountering Traditions’ [23]; Christopher Moriarty, ‘The Early Naturalists’ [71]; Patrick N. Wyse Jackson, ‘Fluctuations in Fortune: Three Hundred Years of Irish Geology’ [?9]; Brendan McWilliams, ‘The Kingdom of the Air: the Progress of Meteorology’ ; Eoin Neeson, ‘Woodland in History and Culture’ [133]; Donal Synnott, ‘Botany in Ireland’ [157]; Peter Foss & Catherine O’Connell, ‘Bogland: Study and Utilization’ [184]; J. H. Andrews, ‘Paper Landscapes: Mapping Ireland’s Physical Geography’ [199]; James P. O’Connor, ‘Insects and Entomology’ [219]; Patrick Sleeman, ‘Mammals and Mammalogy’ [241]; Clive Hutchinson, ‘Bird Study in Ireland’ [262]; Christopher Moriarty, ‘Fish and Fisheries’ [283]; Michael D. Guiry, ‘No Stone Unturned: Robert Lloyd Praeger and the Major Surveys’ [199] . Out of Ireland: Naturalists Abroad: Foster, 1. Introduction [308]; 2. Sheila Landy, ‘Francis Beafort’ [327]; 3. Paul Hackney, ‘Edward Sabine’ [331]; 4. Helena C. G. Chesney, ‘Francis Rawdon Chesney’ [337]; 5. Paul Hackney, ‘Francis Leopold McClintock’ [342]; 6. Helena C. G. Chesney & Robert Nash, ‘Robert Templeton’ [349]; 7. Mary G. McGeown, ‘John Macoun’ [354]; 8. Iain Higgins, ‘Henry Chichester Hart’ [360]; Helena C. G. Chesney, ‘Enlightenment and Education’ [367]; David N. Livingstone, ‘Darwin in Belfast: the Evolution Debate’ [387]; John Wilson Foster, ‘Nature and Nation in the Nineteenth Century’ [409]; Seán Lysaght, ‘Contrasting Natures: the Issue of Names’ [440] ; Dorinda Outram, ‘The History of Natural History: Grand Narrative or Local Lore?’ [461]; David Cabot, ‘Essential Texts in Irish Natural History’ [472]; Martyn Anglesea, ‘The Art of Nature Illustration’ [497]; Michael Viney, ‘Wild Sports and Stone Guns’ [524]; Terence Reeves-Smyth, ‘The Natural History of Demesnes’ [549]; John Feehan, ‘Threat and Conservation: Attitudes to Nature in Ireland’ [573]; Foster, ‘The Culture of Nature’ [597]. Notes on Contributors [636]; Index [641].

The Cambridge Companion to the Irish Novel, ed. John Wilson Foster (Cambridge UP 2006), xix, 286 pp. CONTENTS: Notes on Contributors [vii]; Acknowledgement [ix]; Chronology [x]; 1. Foster, Introduction [1]; 2. Aileen Douglas, ‘The novel before 1800’ [22]; 3. Miranda Burgess, ‘The national tale and allied genres, 1770s-1840’ [22]; 4. Vera Kreilkamp, ‘The novel of the big house’ [60]; 5. Siobhan Kilfeather, ‘The Gothic novel’ [78]; 6. James H. Murphy, ‘Catholics and fiction during the Union (1801-1922)’ [97]; 7. Adrian Frazier, ‘Irish modernisms, ‘1880-1930’ [113]; 8. Bruce Stewart, ‘James Joyce’ [133]; 9. Norman Vance, ‘Region, realism, and reaction, 1922-1972’ [153]; 10. Alan Titley, ‘The novel in Irish’ [171]; 11. Ann Owens Weekes, ‘Women novelists, 1930s-1960s’ [189]; 12. Terence Brown, ‘Two post-modern novelists: Samuel Beckett and Flann O’Brien’ [205]; 13. Elizabeth Grubgeld, ‘Life writing in the twentieth century’ [223]; 13. Elmer Kennedy-Andrews, ‘The novel and the Northern Troubles’ [238]; 14. Eve Patten, ‘Contemporary Irish fiction’ [276].

Between Shadows: Modern Irish Writing and Culture (Dublin: IAP 2009), 257pp. CONTENTS. Preface [vii]; Note on the Text [x]; Foreword [xi]; I. Writers: 1. Emblems of Diversity: Yeats and the Great War [3]; 2. The Islandman: The Teller and the Tale [17]; 3. Against Nature? Science and Oscar Wilde [30]; 4. The Weir: Inheriting the Wind [48]; 5. Stretching the Imagination: Some Trevor Novels [57]; 6. ‘All the Long Traditions’: Loyalty in Barry and Ishiguro [72]; 7. Virtual Irelands: Martin McDonagh [90]; 8. Revisitations: Criticism and Benedict Kiely [101]; 9. The Autocartography of Tim Robinson [118]. II. Writing and Culture: 10. Strangford Lough and its Writers [129]; 11. Blackbird [141]; 12. Guests of the Nation [151]; 13. Getting the North: Yeats and Northern Nationalism [174]; 14. Was there Ulster Literary Life before Heaney? [205]; 15. Bloomsday’s Joyce [219]; 16. Between Two Shadows: Kettle, Lynd and the Great War [235]; Index [253]. Note: a number of the above essays are quoted on the RICORSO pages devoted to the authors cited in the titles and others mentioned in the chapters; see also full-text copy of ‘Revisitations: Criticism and Benedict Kiely’, in RICORSO Library, “Irish Critical Classics”, via index, or direct]

[ top ]

Criticism

|

[ top ]

Commentary

Conor McCarthy, Modernisation: Crisis and Culture in Ireland 1969-1992 (Four Courts Press 2000), assails J. W. Foster’s call for ‘psychological embourgeoisement’ of liberal humanism - which he calls ‘at the least disappointing’- in conjunction with remarks of Longley about the impossibility of leaping from ‘primitivism to post-modernism without an intervening period of historical, cultural and evaluative ground-clearing’. McCarthy writes: ‘What Longley and Foster seem to miss is [Desmond] Bell’s sense of the “contradictions of modernity”. In the desire for “psychological embourgeoisement” and for a “thorough-going empiricism”, we can read signs of a seriously [sic] undialectical form of critique, that is incapable of paying attention to the underbelly of the process of modernisation. [...M]odernisation, as it is implicit in “psychological embourgeoisement” or “evaluative ground-clearing”, is understood as an entirely beneficent process. What Longley and Foster fail to grasp are the full ramifications of the process of whidh they constitute the intellectual analogue.’ (p.36.) Further: ‘[...] a crucial function of this book is to draw attention to the gaps and elisions, the points of hesitation in cultural production in Ireland, and also in the kind of cultural critique exemplified by Foster and Longley. It is in such gaps or at such moments of hesitation that this book tries to locate itself, drawing attention to the tensions between tradition and modernity, between national culture and modernism, between authority and critique.’ (Ibid., p.37; see also quotation from Colonial Consequence, 1991, under Quotations, infra.)

Emer Nolan, ‘Making a Meal of the Mainstream’, review of Between Shadows: Modern Irish Writing and Culture, in The Irish Times (210 March 2002), Weekend: ‘[...] Although the subtitle promises something rather comprehensive, most of the chapters in this collection circle around Foster’s key preoccupations. Essays on Tomás O’Crohan, Tim Robinson, Strangford Lough and on the image of the blackbird in Irish culture combine his long-standing concern with the natural world with his literary interests. Foster is especially concerned to rescue various groups of Irish people that he believes have been “excluded” by Irish academic criticism, guided by its “nationalist” biases. His list of the previously marginalised includes female and gay writers. Such writers do not feature here in any detail, with the exception of an essay on Oscar Wilde’s attitude to science. This particular recuperative project sits oddly with Foster’s clear hostility to those “ideologues in the American university literature classroom” who promote Gender or Gay Studies. Irish scientists and naturalists must also be saved from the condescension of posterity. Foster laments Irish indifference or hostility to Irish combatants in the first World War and to Irish men who served in the Dublin Metropolitan Police and the Royal Irish Constabulary. He notes W. B. Yeats’s failure to acknowledge the imperialist and unionist sympathies of his patron Augusta Gregory’s son Robert, killed in Italy in 1918, in the celebrated elegy “An Irish Airman Foresees his Death”. In general, Foster deplores Yeats’s lack of interest in the war as a theme for poetry; but he goes further in perceiving “behind that aversion a broader Irish recoil from reality and obligation”. In fact, for a critic who dislikes the supposedly homogenising tendencies of “mainstream” Irish criticism, Foster indulges in a fair degree of off-the-cuff stereotyping himself. For example, in the script of a pre-performance talk on a play by Conor McPherson, he announces that while aggressively buying rounds of drink is “very Irish”, real emotional honesty is “not so Irish”. Apparently, it is the unexpected appearance of the latter in an Irish pub that “helps to make The Weir an Irish play of unusual psychological depth”.’ (see also full-text copy of ‘Revisitations: Criticism and Benedict Kiely’, in RicorsoLibrary, “Criticism > Reviews”, via index, or direct])

[ top ]

Quotations

Benedict Kiely: ‘Revisitations: Criticism and Benedict Kiely’, in Between Shadows: Modern Irish Writing and Culture (Dublin: IAP 2009): ‘Benedict Kiely was my own guide around Carleton country in 1970, after I returned to Northern Ireland from Oregon with my PhD; I had written a dissertation on Kiely, Brian Moore and Michael McLaverty, having been converted by Kiely in Oregon from the study of aesthetics to the study of Irish literature. Carleton became the ‘father figure’ in Ulster fiction in the book I was then beginning, Forces and Themes in Ulster Fiction (1974), a book encouraged by my critical mentor, Kiely.’ (p.116 [n.22].)

Further: ‘[...] In 1991 I prefaced my collection of critical essays, Colonial Consequences: Essays in Irish Literature and Culture with what was then an unusual personal account of the originating circumstances of the essays, though I was perhaps unconsciously influenced by both Kiely and Heaney. This kind of personal intervention in Irish criticism is no longer uncommon. (My personal account included my memory of meeting Benedict Kiely in Oregon in 1965.)’ (Idem; n.24.).

Ulster Protestants: ‘tragic in the classic senses of their having wasted their creative potential, misused their power, and failed to recognise their character flaw of overweening pride that has rendered the power brittle and their outlook myopic.’; ‘Having won a victory of sorts in the plantation, the Protestants have been paradoxically enslaved by that victory ever since, never secure, nerve-torn through the need for constant vigilance.’ (Forces and Themes, 1974, p.125.)

Ulster workers: ‘To their enemies, the Ulster working and artisan class is merely bigoted, the Ulster managerial class merely philistine’; ‘for the Protestant North, with its incorrigible non-conformism, industrialism, and political unionism, was not to be part of the literary revival’; ‘the participation of this unqiue Irish city of Belfast in the great international cultural project of modernity.’ (All cited Gerald Dawe, review of Titanic, in The Irish Times, [5] June 1997.)

Ulster Catholics: ‘What [the Ulster Catholic] wants is not progress, a forward looking reversal of decay through agricultural improvement, but rather a return, the recover of a politico-spiritual impossibility - a mythic landscape of beauty and plenitude that is pre-Partititon, pre-Civil War, pre-famine, pre-plantation, and pre-Tudor.’ (‘The Landscape of the Planter and the Gael in the Poetry of John Hewitt and John Montague’, in Canadian Journal of Irish Studies, Vol. 1, No. 2, Nov. 197, p.29; quoted in Edna Longley, ‘Poetry and Politics in Northern Ireland, The Crane Bag, Vo. 9, No. 1, 1985, p.29; also cited in Peter Van de Kamp, ‘Desmond Egan ... [&c.]’, in Geert Lernout, The Crows Behind the Plough, Rodopi, 1991, 148.)

[ top ]

| J. W. Foster, ‘The Critical Condition of Ulster’, in Critical Approaches to Anglo-Irish Literature, ed. Michael Allen & Angela Wilcox [Irish Literary Studies, No. 29] (Colin Smythe 1989), pp.86-102. |

|

‘The critical condition of Ireland at the present time seems undivorceable from the condition of criticism in Ireland. The failure of Irish society is the failure of criticism. First of all, the failure of objectivity, of the generosity that permits objectivity, of the sympathetic faculty that impels generosity. Secondly, the failure of reflection and self-examination. Thirdly, the failure of an intelleigent assertion of legitimate sectarian interest, heritage and identity possible only when objectivity has been striven for. It is surely telling that whereas the isalnd has an enviable canon of literature, a critical canon would be difficult to conjure into existence.’ (.86). Offers commentary on Field Day Pamphlets, and particularly Deane’s Heroic Styles (No. 4), here 88-90: ‘For Deane, Paisley IS Ulster, embodying as he does “violence, a trumpery evangelisicalism, anti-popery and a craven adulation of the ‘British’ way of life”. The recourse of Deane’s argument to caricature (of Ulster Protestants, not Paisley) betrays a reluctance to admit that Protestantisms need not be identical, to admit the possibilities of an authentic, appositive culture.’ (p.89.) Also comments on Declan Kiberd’s Anglo-Irish Attitudes (FD Pamph., No. 6), noting the supple intelligence with which Kiberd ‘demonstrates ... how Irish dramatists frm the late Victorian period onwards - notably Wilde, Shaw and O’Casey - turned the stereotypes on their heads in the service of a belief in an underlying human unity.’ (p.91.) Kiberd’s attack on antithesis and stereotype, behind which lie his feminism and socialism, would seem to incline him to a belief in the essential unity underlying exploitative and divisive stereotypes. / Oddly, though, this manages to leave his nationalism and republicanism intact. Unity is all right, unionism is all wrong. His argument leads him to diminish cultural differences between England and Ireland, and also .... within Ireland. / To do so, he has to conjure out of existences Ulster Protestantism as a cultural entity. There is no Ulster culture because there is no Protestant imagination. Protestant culture is “unionist culture”; it is in fact the Unionist part; no, it is ... the Ulster Defence Association. How disappointing that someone so alert, so correctly alert, to the stereotyping of the Irish by the English should resort to the gery mental processs he deprecates in order to solve the Ulster question. The concept of androgyny, to which Kiberd seems attracted and which makea a nonsense of the binary opposition of steretyped genders, rests on the equality and mutual respect of the constituent sexes, not on the caricaturing and absorption of one by the other. Yet this is what Kiberd’s political androgyny does. ’ (p.91.) Characterises Heaney’s pamphlet (Open Letter, No. 2) as ‘a rejection of literary unionism by refusing the laureatship bestowed on him by Motion and Morrison in their anthology, Contemporary British Poetry’. (p.92.) Eamon Hughes, ‘The Political Unconscious in the Autobiographical Writings of Patrick Kavanagh’, in Michael Allen and Angela Wilcox, eds., Critical Approaches to Anglo-Irish Literature [Irish Literary Studies, No. 29] (Colin Smythe 1989), pp.103ff. |

[ top ]

| ‘The Landscape of Three Irelands: Hewitt, Murphy and Montague’, in Contemporary Irish Poetry, ed. Elmer Andrews, ed. (Macmillan 992), pp.145-67: |

|

‘Baffled, like all of us, by the divisiveness of Irish life, Seamus Heaney has recently seized in desperate hope upon a remark by the Irish historian J. C. Beckett: ‘We have in Ireland an element of stability - the land, and an element of instability - the people’. It is to the stable element that we must look for continuity.’ I am afraid, however, that in literature - and I suspect in history (that is, in the retelling of events) - the landscape is a cultural code that perpetuates instead of belying the instabilities and ruptures Beckett the Protestant chronicler and Heaney the Catholic writer would prefer to escape. I would like to try to demonstrate this with reference to the work of three contemporary Irish poets, John Montague, John Hewitt and Richard Murphy.’ (p.145.) ‘Readers who have read other Catholic writers from Ulster [than Montague] will not be surprised that Montague’s Garvaghey is a landscape in decay. Decay originates in defeat of the Irish nationalismt spirit at each of the climactic historical moments of Montague’s journey back in time. Behind, therefore, the poet’s description of the impoverished landscape he encounters in the 1960s lies the notion the he returns at a time when the nationalist spirit is again under siege. Montague’s Tyrone landscape is a cacaphony of loss ...’ (.p.148) The Ulster Catholic writer has lived so long with the imagery of land decay and land loss that he has become addicted to it; and so, when he encounters evidence of that reversal of decay that his verse has implicitly [149] called for, he baulks at it. There are other reasons for his baulking. What he wants often seems not to be progress, a forward-looking reversal of decay through agricultural improvement, but rather a return, the recovery of a politico-spiritual impossibility - a mythic landscape of beauty and plenitude that is pre-Partition, pre-Civil War, pre-Famine, pre-Plantation and pre-Tudor. ... Moreover, one suspects that Montague finds agricultural and industrial progress alien and unwelcome in part because it is Protestant-inspired.’ (pp.149-50; quoted in part in Edna Longley, ‘Poetry and Politics in Northern Ireland, in The Crane Bag, 9, 1, 1985, p29.) |

Bourgeois man (Irish-style): ‘[...] the autonomous individual may be a bourgeois humanist fantasy, but many of us in Ireland would like to enjoy that fantasy, thank you very much [...] it would be foolish to embrace the psychological socialism of poststructuralism before reaping the reward of psychological embourgeoisement. (Colonial Consequences, Dublin: Lilliput Press 1991, p.231; quoted in Conor McCarthy, Modernisation, Crisis and Culture in Ireland, 1969-1992, Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2000, p.212.) [Note: numerous citations from this text are given elsewhere under separate authors in RICORSO.)

Unionist suasion: ‘[U]nionists could become persuaders in the process of Southerners acknowledging the repressed British components of their society’ (The Idea of the Union: Statements and Critiques in Support of the Union of Gt. Britain and Northern Ireland, Vancouver: Belcouver Press 1995, p.74; quoted in Sean Lysaght, review, Irish Literary Supplement, Fall 1996, p.15.)

Irish dialects?: ‘the local dialect of modernism [...] that dialect has been drowned out by the Romantic tones of Irish nationalism.’

Irish short story: ‘A explanation would include the persistence among Irish people of the gift of anecdote, of idiomatic flair, of the comic tradition and of the real life “characters” (an endangered species today) who offer themselves ready-made for portraiture in the economical short form.’ ( ‘Irish Fiction 1965-1990’ [editorial essay], The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing, ed. Seamus Deane, Derry 1991, p. 939.)

Literary Revival: ‘[an attempt] to emply literature in a resuscitation of elder Irish values and culture that they hoped would transform the reality of the Ireland they inhabited.’ (Irish Revival, p.xvi; cited in James H. Murphy, Catholic Fiction and Social Reality in Ireland, 1873-1922, Conn: Greenwood Press 1997, p.6.)

| Irish Novels 1890-1940: New Bearings in Culture and Fiction (Oxford UP 2008) - |

|

| —For longer extracts, see RICORSO Library, “Criticism”, via index, or attached.] |

Amor patris: ‘In many ways I love all of Ireland and like James Joyce’s Leopold Bloom consider myself Irish because I was born and reared on the island. [...] It is therefore an occasion for genuine regret, even pain, that I do not wish to be a citizen of an Ireland resembling the present Republc. When I lives there, I found it wanting in essentials of ethos, civil liberties, and the consensual patheon of heroes, in its story of itself. One of the most sacred spots in the South of Ireland is the Easter Rising room in the National Museum: I stand in it and feel utterly estranged, as I do if I stand in a Roman Catholic church: both are might formidable spaces, but they exlcude me and moreover wish to exclude me.’ (The Idea of the UnionBelcouver Press 1995, p.61.; quoted in Sean Lysaght, review, Irish Literary Supplement, Fall 1996, p.15.)

Bourgeois man: ‘[...] the autonomous individual may be a bourgeois humanist fantasy, but many of us in Ireland would like to enjoy that fantasy, thank you very much [...] it would be foolish to embrace the psychological socialism of poststructuralism before reaping the reward of psychological embourgeoisement.’ ( Colonial Consequences, Lilliput Press 1991, p.231; quoted in Conor McCarthy, Modernisation, Crisis and Culture in Ireland, 1969-1992, Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2000, p.212.

[ top ]

References

Dufour Catalogue (Spring 1997): ‘A lengthy Introduction by the editor, John Wilson Foster, sets forth the grounds for examination and discovery as he asks the fundamental questions of the contributors: How has Irish nature been studied? How has it been expressed in literature and popular culture? How has it influenced and been influenced by political, economic, and social change?’

[ top ]

Notes

Liam O’Dowd’s new introduction to Albert Memmi, The Colonist and the Colonised [1957] (London: Earthscan 1990), contains the note: ‘I would like to thank John Wilson Foster for his helpful and constructive comments from the other side of the Irish divided. Responsibility for misinterpretation and error is solely my own.’ (pp.64-65.)

A Better Boy (2014) is a dramatic monologue based on the sinking of the Titanic, and performed by Ian MacElhinney of Game of Thrones fame. It takes the form of an interview with William J. Pirie, the shipping magnate, who recalls the life of his nephew Thomas Andrews, the designer of the ship who went down with her. His monologue contests the defeatism associated with the disaster and celebrates the Machine Age, while re-igniting the pain of loss. It was produced the Brian Friel Theatre, Belfast (QUB) and the Brussels Art Centre (both Dec. 2104), and later at the Aspects of Irish Literature Festival, North Down Museum and the Royal Bank of Scotland offices in London (both Sept. 2014).

[ top ]