Life

| [erroneously reg. as Brian Patrick O’Friel in the Catholic and Bernard Patrick Friel resp. in parish and civic records; fam. “Scobie Friel” to his pupils]; b. 9 Jan. 1929 [vars. 5 & 10 Jan.], at Knockmoyle [Killcogher] nr. Omagh, Co. Tyrone, gs. of two Irish-speaking grand-parents; son of Patrick [“Paddy”] Friel, a schoolmaster from Derry, who was orig. appt. to a school in Culmore, nr. Omagh (Co. Tyrone) and later worked in Derry, becoming a Councillor on the Londonderry Corporation; his mother Christina Mary McLoone, worked as postmistress in the Glenties, Co Donegal up to the time of her marriage; his father moved the family to Derry and taught at Long Tower School, Derry, 1939; later moved to Donegal; sometime councillor on Derry Corporation; Friel was initially ed. at his father’s school and later at St. Columb’s College, Derry; grad. BA from Maynooth, 1948; proceeded to St. Patrick’s seminary, 1948-51 [36 months], finding it a ‘very disturbing experience’; |

| entered St. Joseph’s Teacher Training Coll., Belfast; worked as a school-teacher in Derry, 1950-60; published first short story, “The Child” and wrote his first play as The Francophile, 1952; m. Ann Morrison, 1954, with whom four dgs. and a son; lived at 13 Marlborough St., Derry; early plays for BBC NI [Home Service] radio, produced by Ronald Mason, 1958 (A Sort of Freedom, 16 Jan. 1958; To This Hard House, 24 April 1958); contrib. num. early stories in New Yorker from 1959 to 1965 (‘They paid such enormous money I found I could live off three stories a year’); became fulltime writer in 1960; The Francophile performed unsuccessfully by the Ulster Group Theatre, Belfast as A Doubtful Paradise (Aug. 1960); contrib. num. articles to The Irish Press, April 1962-Aug. 1963; issued stories as The Saucer of Larks (1962), set in Glennafushog; wrote The Enemy Within, dealing with the exile of St Columba, staged by the Abbey Company at the Queen’s Theatre, Dublin - his first Abbey production - and played nine nights (from 6 Aug. 1962), with Ray McAnally, Pat Laffan and Michéal O’Briain; transferred to Belfast Lyric Th., Sept. 1963; broadcast on BBC NI and RÉ, 1963; also produced for television with Tom Fleming in the title-role; awarded the William J. B. Macaulay Fellowship [£1,000] - enabling the Minneapolis trip; |

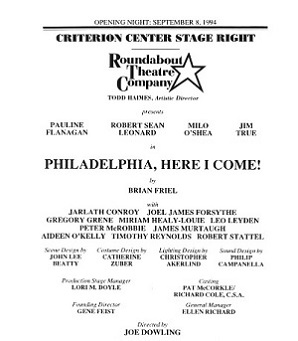

| The Blind Mice (Eblana Th., Dublin, 19 Feb. 1963), in which Fr. Chris, returns from the mission in Communist China and learns a devastating secret; played for 6 weeks; revived at Belfast Lyric, and repeatedly broadcast on RÉ and BBC, up to 1967 but afterwards withdraw by the playwright (‘It’s a play I’m sorry about. It was too solemn, too intense. I wanted to hit too man things.’); invited by Tyrone Guthrie to spend three [var. six] months at his new theatre at Minneapolis as observer, early 1963, watching rehearsals of Hamlet and Chekhov’s Three Sisters (‘those months in America gave me a sense of liberation [...] my first parole from inbred claustrophobic Ireland’); “enabling”, in that it gave him “courage and daring to attempt things”; wrote Philadelphia, Here I Come!, produced for the Dublin Theatre Festival by Edwards-MacLiammoir’s Gate Prods., at the Gaiety Th. (Dublin, 28 Sept. 1964), set on the eve of Gareth O’Donnell’s departure for America from Ballybeg, and featuring a split-character (Gar Public and Gar Private - played resp. by Patrick Bedford and Donal Donnelly; Philadelphia enjoyed a sell-out run by word of mouth - following a review by Frank O’Connor ‘praising with faint damns’ - but recruiting new theatrical talent such as Joe Dowling, who watched the performance every night; successfully revived by Edwards at the Gate in 1965, afterwards transferring to Helen Hayes Th. [240 West 44th Street, Broadway], New York (16 Feb.-1 Oct. 1966), with Patrick Bedford and Donal Donnelly as the two Gareths, and Eamon Kelly, Mairin D. O’Sullivan Launa Saunders, and Mavis Villiers in other roles, winning a director’s Tony for Edwards and nominations for the two lead-actors; Friel moved from Derry to Muff, Co. Donegal, 1966; formally left the Nationalist Party (N.I.) in 1967; issued The Gold in the Sea (1966), stories; |

| [ top ] |

| appt. an Abbey shareholder, 1965; wrote The Loves of Cass McGuire (1966), on American emigration, and gave it to Edwards to direct on its launch in the United States, though both would have preferred a Dublin premier; threatened legal action when he found the script had been tampered wth, and later said in interview, ‘my belief is absolutely and totally in the printed word and this must be interpreted exactly and precisely as the author intended’ (interview of 1968 about Lovers with Lewis Funke]; wrote Lovers (1967), with Eamon Morrissey & Fionnula Flanagan in the leading roles; Lovers toured USA for six months; Philadelphia, Here I Come! was first produced at the London Lyric (20 Sept. 1967); gave the lecture “The Theatre of Hope and Despair” in America, 1967 - afterwards printed in Everyman (No. 1, 1968); issued Crystal and Fox (1968); issued The Mundy Scheme (Olympia Th., Dublin 1969), a satire on the new Irish bourgeoisie concerning the sale of the West of Ireland for development as an American-Irish graveyard to the profit of a scheming Taoiseach - a ‘cynical satire’, according the Seamus Deane (Sel. Plays, 1984, p.15), first offered to the Abbey; Philadelphia filmed by John Quested, 1970; issued The Gentle Island (dir. Vincent Dowling, Olympia Th., 30 Nov. 1971), and later at the Belfast Lyric (18 Oct. 1972); |

| participated in Derry Civil Rights March when 13 marchers were killed by British paratroopers [Regt.] (“Bloody Sunday”, 29 Jan. 1972); wrote The Freedom of the City (premiered at Royal Court Th., London, 17 Feb. 1973), a play already commenced before-hand but ‘sharpened’ by those events, dramatising the inquest relating to occupation of the Derry Guildhall by three squatters, Michael, Lily and Skinner, who are mown down by the Army, with alternate voices of the victims and their killers as well as interludes provided by a drunken ballad singer; moved to the Abbey theatre, Dublin, in 1973, with Raymond Hardie, Eamon Morrissey. and Angela Newman acting; also was produced at the All-Ireland Final by the ’71 Players in 1976; Friel contrib. a ‘Self-Portrait’ to Aquarius (No. 5, 1972); also contrib. ‘Plays Peasant and Unpeasant’ to Times Literary Supplement (17 March 1972); Philadelphia Here I Come! was successfully revived by the Abbey at the Dublin Theatre Fest., 1972 (May & July); wrote Volunteers (1975) - dedicated to Seamus Heaney - also on the Troubles but involving IRA members and an archaeological dig based on the Wood Quay episode in Dublin and resistance to anti-heritage developers; |

| Farewell to Ardstraw and The Next Parish (1976); Living Quarters (1977) [subtitled ‘after Hippolytus’ and reflecting the Theseus-Hippolytus myth], ending with the suicide of Frank Butler, returned from UN service in the Middle East, on learning of his wife’s adultery his own son [her step-son]; Aristocrats (Abbey, 8 March 1979), dir. Joe Dowling, starring Dearbhla Molloy and John Kavanagh, chronicles the disintegration of a Catholic big-house family in Chekhovian-style; pub. Selected Stories (1979); wrote Faith Healer (Abbey 1979), dir. Joe Dowling, with Donal McCann in the title-role, narrating events leading to the death of the title-character Frank Hardy at the hands of a wedding crowd on his return to Donegal, and enacting the complex relationships between his world of imaginary powers and his manager Teddy and wife Grace; premiered in New York with James Mason as Frank Hardy, and panned by critics, closing after 20 performances, 1979; afterwards produced successfully in Dublin with Donal McCann as Frank in a stupendous performance; unsuccessfully performed with Patrick Magee opposite Helen Mirren at the Royal Court (London), 1981, closing after six nights; |

| [ top ] |

| wrote Translations (1980), an exploration study in the politics of language-shift set in Donegal at the time of the nineteenth-century Ordnance Commission and featuring centrally a hedgeschool master Hugh and his forward-looking son Owen; fnd. Field Day Co. with Stephen Rea; Sense of Ireland Exhibition presented in London, 1980; Translations premiered as its first production at Derry Guildhall, 23 Sept. 1980, with Ray MacAnally as Hugh, Rea as Owen, Liam Neeson as Doalty, and Ann Hasson as Sarah [lighting by Rupert Murray]; later professed that Translations ‘was offered pieties that [he] didn’t intend for it’; awarded Ewart-Biggs memorial prize for that play, 1981; Translations produced in London (Hamstead Th., 12 May 1981); his version of Chekhov as Three Sisters was premiered at the Guildhall, Derry (1981); wrote The Communication Cord (1982), a farce produced with a musical score by Keith Donald; awarded DLitt, NUI 1982; The Gentle Island revived in Dublin (dir. Frank McGuinness, Abbey Peacock, Dec.-Jan. 1988); Friel adapted Charles Macklin’s True-born Irishman as The London Vertigo (1992), a one-act play; wrote Dancing at Lughnasa (Abbey Th. April 1990), a memory play which ‘owes nothing to fact’ (Lughnasa, Faber 1990, p.71); |

| Dancing at Lughnasa (1990): set in August 1936 and dramatising the last moments of his aunts’ family life in Donegal - here the Mundy sisters, Chris, Rose, and Kate - shortly before they are forced into economic emigration to the English midlands, as narrated by the illegitimate son of the youngest; a memory-play, partly modelled on Tennessee Williams’s The Glass Menagerie; premiered at the Abbey with Bríd Brennan, Catherine Byrne, Bríd Ní Neachtain and Frances Tomelty in the lead roles, dir. by Patrick Mason with stage-set by Joe Vanek; offered Lughnasa to the Abbey rather than Field Day; the play was directed there by Patrick Mason (Abbey Th. 1990); transferred to National Th., London (1991), elected Best Play and received Year at the Olivier Award; afterwards transferred to New York where it received three Tony Awards on Broadway in 1992 incl. Best Play, Best Director [Mason], and Best Featured Actress [Brid Brennan]; published in a French translation by Jean-Marie Besset as Danser à Lughnasa, for l’imaginaire irlandais, 1996 - and first staged in that version by Irina Brook in 1999; Lughnasa filmed by Pat O’Connor in 1998 to a script by Frank McGuinness with Gerard MacSorley and Meryl Streep, Kathy Burke, et al., acting; released in French as Les Moissons d’Irlande [Irish Harvests]; later produced by Didier Long at the Théâtre de l’Atelier, Sept. 2015, and again by Gaëlle Bourgeois in Paris at Théâtre 13, Sept. 2019, using the 2009 translation by Alain Delahaye, with Emilie Chesnais as Maggie; |

| Faith Healer produced as Témoignages sur Ballybeg, directed by Laurent Terzieff (also playing Frank), 1986; BF appt. to Seanad Éireann by Charles Haughey, serving from 1987 to 1989; an international festivals of his work was centred in the Glenties - and others likewise in 2008 and 2015;Friel formally resigned from Field Day in 1994, having expressed fears that the ‘political atmosphere’ of the group was steering his work [var. in differences with Stephen Rea]; accepted his Tony Award with a paraphrase of Graham Greene (‘Success is only the postponement of failure’);wrote A Month in the Country (Gate Theatre 1992), after Ivan Turgenev - using a literal translation supplied by Christopher Heaney - later played at the Swan Theatre, Stratford-on-Avon, dir Michael Attenborough, with Sara Stewart and Sam Graham (1999);also Wonderful Tennessee (Abbey 1993), a play about the attempt to revive a Lough-Derg style pilgrimage and involving the attempted sacrifice of one of the group; issued Molly Sweeney (Gate 1994), concerning the blindness of the title character and the harmful attempts of her husband Frank and an opthalmological surgeon called Rice to restore her sight at the cost of her inner vision - based on a work by Oliver Sacks (To See or Not to See); transferred to New York and named best foreign play by the New York Drama Critics Circle, 1996; and later produced in Moscow by Lev Dodin at the Maly theatre, St Petersburg, in 2000. |

| [ top ] |

| resigned directorship of Field Day in 1994; Give Me Your Answer Do! (Abbey 1997), produced by Noel Pearson; mbr. Aosdána; Uncle Vanya, dir. Ben Barnes (Abbey Oct. 1998); subject of a theatre festival in Dublin on occasion of his 70th anniversary, April-Aug. 1999, while Dancing at Lughnasa was produced in Paris in December 1999, dir. Irina Brook (dg. Peter Brook]; wrote The Yalta Game, a one-act play, premiered at the Gate Theatre (with Ciaran Hinds and Kelly Reilly in the lead roles), in a three-some with others by Conal McPherson and Neil Jordan (2 Oct. 2001); Faith-healer was revived at the Abbey (Aug. 2002), with John Kavanagh as Frank Hardy; also at Almeida Th., London (Nov. 2001), dir. Jonathan Kent with Ken Stott, Ian McDiarmid and Geraldine James; wrote The Bear: A Vaudville and Afterplay, produced jointly at the Gate (March 2002) - the latter on to the Gieldgud Th., London, West End (Oct. 2002), with John Hurt and Penelope Wilton; based on characters from Chekhov - viz., Andrey Prozorov from Three Sisters and Sonja Serebriakova from Uncle Vanya; issued Performances (2003), a play inspired by love affair between Janacek and Kamila Stosslova [var. Anezka Ungrova]; Dancing at Lughnasa, revived at the Gate (2004), with Ben Price, Derbhle Crotty, Peter Gowen, Andrea Irvine, John Kavanagh, Aisling O’Neill and Catherine Walsh; wrote The Home Place (Gate Th., Feb. 2005), a study of the Anglo-Irish ascendancy’s love for the Irish world they inhabit in times of Land League agitation, set in 1878 and featuring the visit of English phrenologists to measure the heads of Irish peasants; dir. Adrian Noble, with Tom Courtney as Christopher Gore, Derbhle Crotty as Margaret, and Hugh O’Conor as David Gore; transferred to London’s Comedy Theatre in May; winner of “Best Play” in London Evening Standard Theatre Awards; 25th Anniversary of Translations widely celebrated in Irish media, North and South, 2005; Molly Sweeney produced as Molloy and directed by Laurent Terzieff in a translation by Alain Delahaye, 2005; |

| Friel elected a Saoi of Aosdána for ‘singular and sustained distinction in the arts’, and afterwards presented with a gold torc by President Mary McAleese to mark the fact, 22 Jan. 2006 (‘extreme unction [...] Aosdana’s last rites’); second revival of Faith-healer at the Gate Th., Dublin, Feb. 2006, with Ralph Fiennes and Ian McDiarmid, dir. by Jonathan Kent; toured to Almeida Th. (Broadway, NY 2006), still with Fiennes and McDiarmid - who won Tony Award for his performance (calling the role of Frank ‘one of the most emotionally intricate and musically perfect pieces for the stage in the English language’; Seamus Heaney suffers a stroke at Friel’s house during the night of his Friel’s birthday party, and his carried from the house Lazarus-style (vide Heaney’s subsequent poem and collection The Human Chain); Friel received the Ulysses Award of UCD, June 2009, the medal being presented by Seamus Heaney, and was made the subject of a conference in Paris celebrating his 80th year; Faith Healer, The Yalta Game and Afterplay staged at the Gate Sept. 2009; excerpts from Philadelphia, Here I Come! Translations, and Dancing at Lughnasa read at Abbey Theatre ‘Birthday Celebration for Brian Friel’, 13 Sept. 2009, with Thomas Kilroy and Seamus Heaney readings and performance of ‘Friel songs’; Lughnasa played at The Old Vic, London, 2009, with Niamh Cusack [Maggie] and Finbar Lynch [Jack]; |

| Faith Healer revived at the Gate with Owen Roe [lead], Kim Durham and Ingrid Craigie, dir. Robin Lefèvre (Jan.-Feb. 2010), and toured to Edinburgh, Aug. 2010; commissioned portrait of Friel by Mick O’Dea unveiled at the National Gallery Portrait Collection, Dublin, 16 July 2010; new production of Molly Sweeney, with Dawn Bradfield in the title role (Gate 2011); his translation-version of Hedda Gabler played in The Old Vic (London) in Sept. 2012; Friel donated his literary papers to the National Library of Ireland [NLI] in 2001; he protested with John Hume against Foyle sewage plan at Carnagarve, Co. Donegal; elected Donegal Person of the Year, 2010; continued to live in Donegal but latterly moved from Muff to Dromoweir, nr. Greencastle; subject of special section of The Irish Times at 80 (27 June 2011); suffered the death of his eldest dg., Patricia [“Paddy”], 2012; Molly Sweeney played at the Print Room (London, 2103), with Dorothy Duffy and Ruairi Conaghan; Philadelphia and Molly Sweeney were revived concurrently at the Lyric Theatre, Belfast, in Feb.-March 2014; d. 2 Oct. 2015, after long illness; Broadway theatres dimmed their marquee lights for one minute on 8 Dec. 2015 to mark his death; he presented his papers to the NLI in 2001. DIW DIL OCIL FDA |

[ top ]

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

| Friel’s 70th birthday was celebrated in 1999 with a Friel Festival in Dublin when ten of his plays were staged or presented as dramatic readings at different city venues. |

[ top ]

Works| Drama | |

| Plays [first productions] | |

|

|

| [ top ] | |

| Plays (publication) | |

|

|

| [ top ] | |

| Selected & collected drama | |

|

|

|

|

| [ top ] | |

| Short Fiction (original collections) | |

|

|

| Short fiction (selected & collected) | |

|

|

| Commentary | |

|

|

|

|

| [ top ] | |

| Miscellaneous (selected) | |

|

|

[ top ]

Bibliographical details

The Saucer of Larks (London: Gollancz 1962) contains the title story with “The Foundry House” [concerning Joe Brennan, the lodge-keeper to the Hogan family; material for Aristocrats]; “The Potato Gatherers”; “The Gold in the Sea”; “The Illusionists”; “Everything Neat and Tidy”, et al.]Note: dramatised Chekhov’s “Lady with a Lapdog” and later wrote Afterplay, featuring the two main characters from that story in an imagined subsequent meeting.

[ top ]

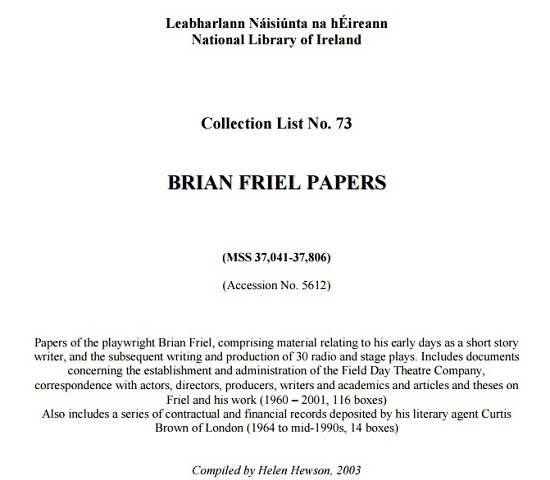

Briel Friel Papers at the National Library of Ireland (2003)

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann

National Library of Ireland

Collection List No. 73

BRIAN FRIEL PAPERS

(MSS 37,041-37,806)

(Accession No. 5612)Compiled by Helen Hewson, 2003; available at NLI as PDF

Papers of the playwright Brian Friel, comprising material relating to his early days as a short story writer, and the subsequent writing and production of 30 radio and stage plays. Includes documents concerning the establishment and administration of the Field Day Theatre Company, correspondence with actors, directors, producers, writers and academics and articles and theses on Friel and his work (1960-2001, 116 boxes) Also includes a series of contractual and financial records deposited by his literary agent Curtis Brown of London (1964 to mid-1990s, 14 boxes).

[ top ]

| Select annual listing | ||

[ top ] |

||

[ top ]

[ top ]

[ top ]

|

||

|

||

|

[ top ]

Bibliographical details

Alan Peacock, ed., The Achievement of Brian Friel (Gerrards Cross 1993), 267pp.; CONTENTS: Alan Peacock, Introduction [xi]; John Cronin, ““Donging the Tower” - The Past Did Have Meaning’: The Short Stories of Brian Friel’ [1]; Neil Corcoran, ‘The Penalties of Retrospect: Continuities in Brian Friel’ [14]; Elmer Andrews, ‘The Fifth Province’ [29]; Desmond Maxwell, ‘“Figures in a Peepshow”: Friel and the Irish Dramatic Tradition’ [49]; Christopher Murray, ‘Friel’s “Emblems of Adversity” and the Yeatsian Example’ [69]; Thomas Kilroy, ‘Theatrical Text and Literary Text’ [91]; Seamus Deane, ‘Brian Friel: The Name of The Game’ [103]; Alan Peacock, ‘Translating the Past: Friel, Greece and Rome’ [113]; Robert Welch, ““Isn’t This Your Job? - To Translate?”: Brian Friel’s Languages’ [134]; Sean Connolly, ‘Translating History: Brian Friel and the Irish Past’ [149]; Richard York, ‘Friel’s Russia’ [164]; Joe Dowling, ‘Staging Friel’ [178]; Terence Brown, ““Have We a Context?”: Transition, Self and Society in the Theatre of Brian Friel’ [190]; Fintan O’Toole, ‘Marking Time: from Making History to Dancing at Lughnasa’ [202]; John McVeagh, ““A Kind of Comhar”: Charles Macklin and Brian Friel’ [215]; Seamus Heaney, ‘For Liberation: Brian Friel and the Use of Memory’ [229]; 241; Select Bibliography, 254; Notes on Contributors, 259; Index, 263. [See Bridget O’Toole’s review of this collection under Commentary [as infra.]

| Anthony Roche, ed., Irish University Review, 29, 1 [“Brian Friel Special Issue”] (Spring-Summer 1999] - CONTENTS: Anthony Roche, ‘Introduction: The Worlds of Brian Friel’ [vii-x]; Seamus Heaney, ‘The Real Names’ [1-5]; Harry White, ‘Brian Friel and the Condition of Music’ [6-15]; Christopher Murray, ‘Friel and O’Casey Juxtaposed’ [16-29]; George O’Brien, ‘“Meet Brian Friel": The Irish Press Columns’ [30-41]; Patrick Burke, ‘Them Class of People’s a Very Poor Judge of Character": Friel and the South’ [42-47]; Helen Lojek, ‘Brian Friel’s Gentle Island of Lamentation’ [48-59]; Frank McGuinness, ‘Faith Healer: All the Dead Voices’ [60-63]; Robert Tracy, ‘The Russian Connection: Friel and Chekhov’ [64-77]; Brian Friel, ‘From Uncle Vanya: A Version of the Play by Anton Chekhov’ [78-82]; Thomas Kilroy, ‘Friendship’ [83-89]; Anna McMullan, ‘“In Touch with Some Otherness”: Gender, ‘Authority and the Body in Dancing at Lughnasa’ [90-100]; Catriona Clutterbuck, ‘Lughnasa "After" Easter: Treatments of Narrative Imperialism in Friel and Devlin’ [101-118]; Csilla Bertha, ‘Six Characters in Search of a Faith: The Mythic and the Mundane in "Wonderful Tennessee"’ [119-135]; Nicholas Grene, ‘Friel and Transparency’ [136-144]; Anthony Roche, ‘Friel and Synge: Towards a Theatrical Language’ [145-161]; José Lanters, ‘Brian Friel’s Uncertainty Principle’ [162-175]; Richard Pine, ‘Love: Brian Friel’s Give Me Your Answer, ‘Do!’ [176-188]. Book Reviews incl. Peter Raby, ‘review of Wilde the Irishman by Jerusha McCormack; Christopher Murray, ‘review of The Irish Play on the New York Stage 1874-1966 by John P. Harrington; Brian Arkins, ‘review of Images of Joyce by Clive Hart; C. George Sandalescu; Bonnie Kime Scott; Fritz Senn; Jean Dunne, ‘review of The White Beach: New and Selected Poems 1960-1998 by Leland Bardwell. | |||||||

| —Contents page available at JSTOR - online. | |||||||

|

Richard Pine, The Diviner: The Art of Brian Friel [2nd rev. edn.] (Dublin: UCD Press 2000), 409pp. Preface to the Second Edition [vii]; Acknowledgements [xiii]; List of abbreviations [xv]; Chronology [xvii]; INTRODUCTION [1]: Survey of the work [2]; Language [7]; Literature and politics [18]; Liminality, splitting and the gap [25] Memory and space [31]. PART I - Private Conversation: The Landscape Painter [37]; Man, place and time [37]; Drama as ritual [56]; The playwright’s commitment [67]; Naming things [74]; 2:The Short Stories [77]; Divination [77]; Homecomings [83]; Dignity and respectability [86]. PART II - Public Address: Plays of Love [97]; Radio drama [97]; The struggle of love [103]; Embarrassment [113]; Plays of Freedom [120] Dispossession [120]; Loyalties [126]; Laying ghosts [142]. PART III - Politics: A Field Day [163]; Plays of Language and Time [179]; History and Fiction [179]; Language and society[198]; Translating [209]; A National Epic? [215]; Language and identity [218]; Vertigo [228]; The gap [234]; Travesties [246]. PART IV - Music: Plays of Beyond [257]; Beyond [257]; The Child [260]; Ritual as drama [268]; Storytelling [279]; Blindness [288]; Love [304]; Magic [316]; A question of form[316]; Versions of the truth [322]; Ireland and Russia [333]. Conclusion [344]. Appendix: George Steiner and Brian Friel [359]; Notes [364]; Index [399].

[See COPAC summary: Survey of the work, language, literature and politics, liminality, splitting and the gap, memory and space. Part I Private conversation; the landscape painter; the short stories. Part II Public address: plays of love; plays of freedom. Part III Politics: a field day; plays of language and time. Part IV Music: plays of beyond; magic. Appendix: Brian Friel and George Steiner. Written in cooperation with Friel and including an assessment of his latest work.]

F[rancis] C[harles] McGrath, Brian Friel’s (Post-)Colonial Drama: Language, Illusion and Politics (Syracuse UP 1999), 312pp. CONTENTS: Acknowledgments [ix]; Abbreviations [xi]; Chronology [xiii]; 1. Introduction [1]; 2. Friel and the Irish Art of Lying [13]; 3. Enabling Fictions: The Short Stories [49]; 4. Apprenticeship: The Loves of Cass McGuire and the Early Plays [64]; 5. The End of Innocence: The Freedom of the City and Volunteers [96]; 6. Family Matters: Living Quarters and Aristocrats [135]; 7. Postmodern Memory: Faith Healer [158]; 8. (De)mythology: Translations, The Communication Cord, and Field Day [177]; 9. Making History [210]; 10. Dionysus in Ballybeg: Dancing at Lughnasa [234]; 11. Blindsight: Molly Sweeney [248]; 12. Conclusion, Resistances and Reconsiderations [281]. Texts Cited [299]; Index 309.

Anthony Roche, ed., The Cambridge Companion to Brian Friel (Cambridge UP 2006), xvi, 177pp. Contribs. [vii]; Acknowledgements [x]; Note on the text [xi]; Chronology [xii]; Antony Roche, ‘Introduction’ [1]; Thomas Kilroy, ‘The Early Plays’ [6]; Frank McGuinness, ‘Surviving the 1960s: three plays by Brian Friel 1968-1971’ [18]; Stephen Watt, ‘Friel and the Northern Ireland “Troubles” play’ [30]; Anthony Roche, ‘Family affairs: Friel’s plays of the late 1970s’ [41]; Nicholas Grene, ‘Five ways of looking at Faith Healer’ [53]; Martine Pelletier, ‘Translations, the Field Day debate and the re-imagining of Irish identity’ [66]; Helen Lojek, ‘Dancing at Lughnasa and the unfinished revolution’ [78]; George O’Brien, ‘The late plays’ [91]; Richard Pine, ‘Friel in Russia’ [104]; Patrick Burke, ‘Friel and performance history’ [117]; Richard Allen Cave, ‘Friel’s dramaturgy: the visual dimension’ [129]; Anne McMullan, ‘Performativity, unruly bodies and gender in Brian Friel’s drama’ [142]; Csilla Bertha, ‘Brian Friel as a postcolonial playwright’ [154]; Select Bibliography [166]; Index [172].

Scott Boltwood, Brian Friel, Ireland, and the North [Cambridge Studies in Modern Theatre] (Cambridge UP 2007), xiv, 257pp. Chapters: Introduction - Friel, Criticism, and Theory; 1. The Irish Press essays, 1962-1963: Alien and Native; 2. The Plays of the 1960s: Assessing Partition’s Aftermath; 3. The Plays of the 1970s: Interrogating Nationalism; 4. Plays 1980-1993: The North; 5. Plays 1994-2005: Retreat from Ireland: The Home Place.]

“Friel at 80”, The Irish Times (Monday 27 June 2011) [incls. Thomas Kilroy, ‘In celebration of a friend’; Sara Keating, ‘Delving into a divided Donegal landscape’; Colm Tóibín, ‘A craft of words to work a halo around the ordinary’; Fintan O’Toole, ‘Tracing a rocky path from the past’]; Fiach MacConghail, ‘Brian Friel: A Dramatic Life’; other tributes by Catherine Byrne, Joe Dowling, Kathleen Watkins, Stephen Rea, Rosaleen Linehan, Derbhle Crotty, Patrick Mason, Peter Fallon, Eamon Morrissey, Michael Colgan, & Conor McPherson].

[ top ]

Richard Rankin Russell, Modernity, Community, and Place in Brian Friel’s Drama [Irish Studies] (Syracuse UP 2013), xi, 317pp. CONTENTS [Chaps.]: Mediascape, Harvest, Crash: Philadelphia, Here I Come! and Gar O’Donnell’s Modernity; "Placing the Dead of the Troubles": The Imagined Ghostly Community of The Freedom of the City; Faith healer: From the Geopathic Shudder to the Embrace of Ritualized, Performative Place; Translations: Lamenting and Accepting Modernity; Dancing at Lughnasa: Placing and Recreating Memory.

Aidan O’Malley, Field Day and the Translation of Irish Identities: Performing Contradictions (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan 2011), viii, 249pp. - see Friel-related contents: Translations (pp.26-41), The Communication Cord (pp.57-67), Three Sisters (pp.67-76), Making History (pp.41-53).

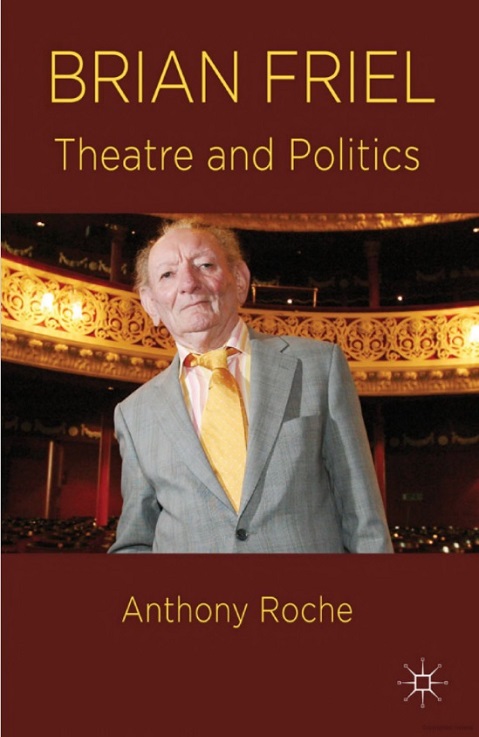

Anthony Roche, Brian Friel: Theatre and Politics (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan 2011), ix, 235pp. CHAPTERS: Introduction; Escaping Containment: the Early Plays; Friel and the Director: Tyrone Guthrie and Hilton Edwards; The Operation of Fantasy; Changing the Direction of Theatre: Friel, John Osborne and David Storey; The Politics of Space: Reconfiguring Relationships; Translations: An Enquiry into the Disappearance of Lt. Yolland; History and Memory; Negotiating the Present; Bibliography; Index.

[ Available at Google Books - online; accessed 07.04.2017. ]

[ top ]

References

Helena Sheehan, Irish Television Drama, A Society and Its Stories (RTE 1987). lists Crystal and the Fox, Brian Friel/Noel Ó Briain; Mr Sing, My Heart’s Delight, Brian Friel, adpt. Brian MacLochlainn/MacLochlainn (1974) ; Loves of Cass Maguire, The, Friel/Jim Fitzgerald (1969)

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 3: selects Translations [1207-36]; & REMS 564, 630, 632-33, 642, 643, 644, 648-54 passim, 1137, 1140, 1142-43, 1313, 1372n, 1377; BIOG & COMM, 1206-07 [as above]; also J[ohn] H. Andrews, ‘Translations and a Paper Landscape’, in The Crane Bag, Vol. 7, No. 2 (1983), pp.118-24, on the role of the history of the Ordnance Commission in Translations; see Crane Bag 7, no. 2 (1983) [FDA3].

Robert Hogan, Seven Irish Plays, Introduction (Minnesota UP 1967), cites The Francophile (Group Theatre, Belfast), The Enemy Within (Abbey), and Blind Mice [chk. dates].

| Some Page Links |

|

| See also |

Brian Friel - life in theatre: in pictures (Guardian, 2 Oct. 2015) |

[Note: The above links largely drawn from Richard Pine, “Brian Friel Obituary”, in Guardian (2 Oct. 2015) - online; see also copy - as attached. ] |

[ top ]

Gallery Press (1995 Cat.) lists reprints of the following [with orig. dates]: The Enemy Within [1962]; The Loves of Cass Maguire [1967]; The Freedom of the City [1973]; Living Quarters [1977]; Faith Healer [1979]; Three Sisters [1981]; and A Month in the Country [1992]; also, Bibliography of works.

Books in Print (1994): Aristocrats (Dublin: Gallery Press 1980, 1993); Communication Cord (Dublin: Gallery Press 1983, 1989); Crystal and Fox (London: Faber 1970, Gallery 1985, 1993); Dancing at Lughnasa (Lon/Bost: Faber 1990, 1994), also French’s Acting ed. (1992); Enemy Within (Newark, Proscenium 1975; Dublin: Gallery Press 1979, 1993); Fathers and Sons, after Turgenev (Faber 1987, 1994); Faith Healer (London: Faber 1980; Dublin: Gallery Press 1991, 1993); Freedom of City (London: Faber 1974; Dublin: Gallery Press 1992) 1992, 1994); Gentle Island (London: Davis-Poynter 1973; Dublin: Gallery Press 1992, 1993); Living Quarters, after Hippolytus (London: Faber 1978; rep. Gallery 1992, 1993); London Vertigo, after Macklin (Dublin: Gallery Press 1990, 1993); Lovers (NY: Farrar, Straus & Giroux 1968; London: Faber 1969); Loves of Cass Maguire (London: Faber 1967; Dublin: Gallery Press 1984, 1992); Making History (Lon/Bost: Faber 1988, 1994); Philadelphia, Here I Come! (London: Faber 1967, 1994); Selected Plays, ed. Seamus Deane (London: Faber 1984, 1994); Three Sisters, trans. from Chekhov (Dublin: Gallery Press 1981, 1993); Translations (London & Boston: Faber 1981, 1994); Volunteers (Gallery 1989, 1993); Wonderful Tennessee (London: Faber, 1993, 1994; Dublin: Gallery Press 1993); Friel, ed., I. S. Turgenev, A Month in Country (Dublin: Gallery Press 1992, 1993); The Diviner, The Best Stories of Brian Friel (Dublin: O’Brien Press; London: Allison and Busby 1983)[WHITAKER & BNB].

Acknowledgement: Numerous bibliographical details in the above listing under Criticism [supra] supplied by Sam McCready, University of Maryland Baltimore County <email>.

Website: There is an informative Brian Friel teaching webpage at Umea University, Sweden [online; extant at 27.03.2011.]

[ top ]

Notes

Faith Healer (1979): Three The monologues in which the final days of the faith-healer Frank’s career are rehearsed on stage in monologues by him, his manager Teddy and his wife Grace Hardy. Crucial to their accounts is the story of an incident in a Welsh village when he cured ten people. Teddy’s monologue reveals that Grace Hardy has committed suicide, while Frank’s second monologue suggess that he goes to his death after failing to heal a cripple near his Donegal home and implies that, in dying, he experiences a sense of homecoming. Nothing is entirely clear, however - neither the death of Frank nor Grace and the play essentially revolves around the uncertain nature of his gift whose reality he himself doubts and which seems unsustainable in the future. The play was premiered in Broadway on 5 April 1979 with James Mason, Clarissa Kaye and Donal Donnelly; it was produced at the Abbey in August 1980 with Donal McCann, Kate Flynn and John Kavanagh under the direction of Joe Dowling. Subsequent performances incl. a 1994 revival under Dowling at the Long Wharf Theatre (London), with McCann together with Judy Geeson and Ron Cook. A revival at the Almeida Th. (King’s Cross, London) in 2001 was directed by Jonathan Kent and reviewed by Paul Taylor in Independent [UK], 1 Dec. 2001 (p.8). Kent directed it at the Gate Theatre, Dublin, in Spring 2006, with Ralph Fiennes, Ingrid Craigie, and Ian McDiarmid in the three roles, moving it to the Booth Theatre, NY, in May 2006 (with Cherry Jones as Grace). On this occasion it received four Tony Awards. It subsequently appeared at the Abbey Th., Dublin (Aug. 2002), and toured Ireland afterwards. Joe Dowling took the lead in a revival at the Guthrie Theater (Minneapolis) in Oct. 2009. It was played in a Portuguese in Ribeira, Natal, in Rio do Norte, Brasil, in June 2012 and has been played at Hofstra, Long Island in the early 2000s.

Translations (1980): ‘Translations [...] is perhaps his most controversial play[. It] is about the mapping of Ireland by the Ordnance Survey in the 1830s. Focusing on the translation of Gaelic place names into English, thereby providing a dramatic metaphor for the Anglo-Irish historical relationship, it proved to be a landmark in the debates about cultural identity and historical revisionism that were a feature of Irish intellectual life in the 1970s and 1980s. Seamus Deane described it as “a sequence of events in history which are transformed by his writing into a parable of events in the present day”. Praising its depiction of colonialism, the critic James Fenton welcomed it as a “vigorous example of corrective propaganda”. But the historian Sean Connolly complained of an extreme “distortion of the real nature and causes of cultural changes in nineteenth-century Ireland”. Friel insisted he had not written a play about Irish peasants being suppressed by English sappers. “The play has to do with language and only language. And if it becomes overwhelmed by that political element, it is lost.”’ (See Irish Times Obituary, 2 Sept. 2015 - available online; accessed 02.10.2015.)

Friel on Translations (in interview with Fintan O’Toole): ‘Were you aware of almost being canonised after Translations?’ ‘Ach, not at all. Ah, no, that’s very strong. But it was treated much too respectfully. You know, when you get notices, especially from outside the island, saying, “If you want to know what happened in Cuba, if you want to know what happened in Chile, if you want to know what happened in Vietnam, read Translations,” that’s nonsense. And I just can’t accept that sort of pious rubbish.’ (O ‘toole, Interview in In Dublin, 1982; )

Further remarks (on language): ‘[...]. The whole language one is a very tricky one. The whole issue of language is a very problematic one for us all on this island. I had grandparents who were native Irish speakers and also two of the four grandparents were illiterate. It’s very close, you know. I actually remember two of them. And to be so close to illiteracy and to a different language is a curious experience. And in some way I don’t think we’ve resolved it. We haven’t resolved it on this island for ourselves. We flirt with the English language, but we haven’t absorbed it and we haven’t regurgitated it in some kind of way. It’s accepted outside the island, you see, as “our great facility with the English language” - [Kenneth] Tynan said we used it like drunken sailors, you know that kind of image. That’s all old rubbish. A language is much more profound than that. It’s not something we produce for the entertainment of outsiders. And that’s how Irish theatre is viewed, indeed, isn’t it? [...] It’s back to the political problem: it’s our proximity to England; it’s how we have been pigmented in our theatre with the English experience, with the English language, the use of the English language, the understanding of words; the whole cultural burden that every word in the English language carries is slightly different to our burden. Joyce talks in the Portrait of his resentment of the [English] Jesuit priest because his language, “so familiar and so foreign, will always be for me an acquired speech”, and so on.’ (Idem; rep. in Irish Times, 2 Sept. 2015 [obituary article - available online].)

[ top ]

The Mundy Scheme; or, May We Write Your Epitaph Now, Mr Emmet? (1969), a full-length play with 12 male and 3 female players: ‘Ireland has a new leader and a cabinet minister presents a scheme for prosperity. Offer the bogs and unproductive areas to sentimental Irishmen abroad as a final resting place. The scheme gains momentum and infighting begins. After a great deal of treachery and double-dealing, the leader ends up as the only one whO’ll profit from the scheme.’ (See Samuel French - online; adds review from The Critic: ‘A savage, albeit uproarious satire on Irish politics with a good many well-aimed whacks at Americans’.)

Dancing at Lughnasa (1990), a play set in Ballybeg, Co. Donegal - Friel’s fictional townland - it deals with the household of the Mundy sisters, Chris[tine], Rose and Kate, living in a rural home in 1936 some years before they are dispersed by economic hardships. The narrative is conducted by Michael Evans, the son of the youngest sister Rose with a travellings salesman from Wales who twice returns to visit. An elder brother, Fr. Jack, who has served as a priest among the Ryangan tribespeople in Africa, where he has contracted animistic [pagan] ideas, hence providing comic relief but also an element of critique for Irish Catholicism of the period. Chris, the oldest and the breadwinner in her capacity as a school-teacher - shortly to be unemployed - was once a participant in the Independence movement, is now an upholder of strict morality and convention and an admirer of De Valera. Rose’s illegitimate child provides a source of strain in the all-female family unit yet at the end they celebrate the Celtic festival of Lughnasa by dancing in a moment which quickly became iconic as an expression of Irish spiritual strength in the face of real adversity (much of it the product of a political policy of isolationism).

Film version: The play was filmed by Pat O’Connor (dir.), with screenplay by Frank McGuinness. The dram. pers. were acted by Meryl Streep, Kathy Burke, Sophie Thompson, Bríd Brennan, Catherine McCormack, Rhys Igfans and Michael Gambon; music in dancing scene by Bill Whelan; premiered in Dublin, Sept. 1998.

Making History was revived in Dublin in 2005, under direction of Geoff Gould for Ouroboros with as Denis Conway as Hugh O’Neill; Sinead Cuthbert won the Irish Times Award for Best Costumes; the production then toured Ulster. In 2007 by a sponsored journey along O’Neill’s and O’Donnell’s route to Kinsale and O’Neill’s subsequent journey from Mellifont Abbey to Rathmullan, resulting in performances at 15 OHP sites in Ireland, five in Northern Ireland - including Dungannon and Rathmullen - and three in Europe, including Louvain. the Rathmullen performance will be attended by Mary McAleese, President of Ireland, and will be staged in an Irish army tent. For Conway, it is ‘a play about how “official” histories are made and interpreted, it is particularly timely to be staging Friel’s play now that political stability has finally been achieved on the island of Ireland.’ (See Denis Conway, ‘History takes flight’, in The Irish Times, 7 July 2007, Weekend.)

The Home Place (Gate, Feb. 2005): set in The Lodge, an Anglo-Irish house in Ballybeg in 1878, it revolves around a love triangle involving widowed Anglo-Irish landlord Christopher Gore and his son David, both of whom love their housekeeper Margaret O’Donnell, daughter of the local schoolteacher, a drunkard but an man of understanding; while Christoper’s racist English cousin Richard arrives to measure the skulls of Irish natives and land-league agitators manage to banish him with his phrenological apparatus to the perplexity of Gore, torn between loyalties and cultures, finally discovering that, though the Lodge is his home, he has not future in it. Premiered at the Gate Th. (Feb. 2005), Adrian Noble directing, with Tom Courtenay as Gore and Derbhle Crotty as Margaret; other parts being played by Hugh O’Conor (David); Barry McGovern (school-teacher); Nick Dunning (Richard); Pat Kinevane (Richard’s assistant), Adam Fergus, Michael Judd, Brenda Larby, Laura Jane Laughlin.

Afterplay: Richard Pine writes (Books Ireland, April 2009: Corrigenda): ‘[P]lease note a small but important error in the review of Friel’s Hedda Gabler by Eamonn Kelly. He writes: “He [Friel] dramatised Chekhov’s short story “Lady with Lapdog” with great success and later he took two of the main characters from that story and dramatised a meeting between them years later in the piece Afterplay.” / The two characters in Friel’s Afterplay are in fact Andrey Prozorov from Three Sisters and Sonja Serebriakova from Uncle Vanya. The dramatisation of Dmitri Dmitrich Gurov and Anna Sergeyevna from “Lady with Lapdog” (in The Yalta Game) bears no relation to the characters in Afterplay.’ In his attached apology, Eamonn Kelly replies, ‘I’m afraid l trusted my memory without checking.’ (BI, p.72.)

[ top ]

Ordnance Survey (I): The acknowledged chief source of Friel’s conception of the work of the 1835 Ordnance Commission is J. H. Andrews, A Paper Landscape: The Ordnance Survey in Nineteenth Century Ireland (OUP 1975) [see infra]. Andrews’ offered a rebuttal of the use made of it in ‘Notes for a Future Edition of Brian Friel’s Translations’, in Irish Review, 13 (Winter 1992/93), pp.93-106. Friel’s response to that was published in Christopher Murray, ed., Brian Friel: Essays, Diaries, Interviews 1964-1999 (2000).

Bibliography: John [Harwood] Andrews, A Paper Landscape: The Ordnance Survey in Nineteenth-century Ireland (Oxford: Clarendon Press 1975), xxiv, 350pp., [9] leaves of pls., with a rep. edn from Lilliput Press (Dublin 2002). This is incontrovertably identified as the source in Brian Friel, John Andrews & Kevin Barry, ‘Translations and a Paper Landscape’, Crane Bag, 7, 2 [Forum Issue] (1983), pp.118-24. See also J. H. Andrews, History in the Ordnance Map: An Introduction for Irish Readers (Dublin: Ordnance Survey Office [Phoenix Park] 1974), [4], 63pp., with facs. + maps [pb.].

Ordnance Survey (2): Friel edited and introduced The Last of the Name by Charles McGlinchey (Belfast: Blackstaff Press 1986), in which the work of ‘sappers’ [i.e., engineers] of the Ordnance Survey in 1835 are mentioned in connection with the theft equipment by a ‘lad’ one day when they were working ‘out on the face of Bulaba somewhere about Currachbeag’ and its recovery and restitution to them by McGlinchey’s father ‘before trouble could be made about it’ (p.10f.).

Note: Other sources are Colby’s memoir of Londonderry [i.e., the sole actual issue of the Historical Memoirs of the Ordnance Commission] and P. J. Dowling’s The Hedge-Schools of Ireland (London: Longman, Green & Co. 1935), 182pp. [for extracts see attached.]

[ top ]

Field Day Company (I): The Field Day Company’s Certificate of incorporation was signed on 12 Aug. 1980 [Friel and Rea] and received by Paddy Woodworth (as Company Secretary, on 22 Aug.) The company was registered at the Orchard Gallery, Derry and the first meeting of directors was held at Friel’s home, Ardmore, Muff, Co. Donegal, 14 Sept. 1980. New directors Heaney, Deane, Hammond and Paulin were proposed and elected to board meeting held at Clarendon, St. Dublin, Mon 3 Aug. 1981; tje First Annual General Meeting, was held at the Gresham Hotel, Dublin, 30 Sept. 1981.(See Ciaran Deane, MA Thesis, UU 2006.)

Field Day Company (II) - The Manifesto: ‘To forge a Northern-based theatre company which would rehearse and tour the North and then tour throughout the whole of Ireland; secondly to concentrate on smaller venues, where theatre is rarely seen; and finally to perform plays of excellence in a distinctively Irish voice that would be heard throughout the island’. (See ‘Field Day Company to present Chekhov’s Three Sisters, in Derry Journal, 19 June 1985, p.5; quoted in Marilyn Richtarik, Acting Between the Lines: the Field Day Company and Irish Cultural Politics, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1994), p.109; cited in Loredana Salis, ‘‘“So Greek with Consequence””: Classical Tragedy in Contemporary Irish Drama’, PhD Diss., UUC, 2005.)

Ballybeg (I): ‘A glance at any six-inch Ordnance map will reveal the strange names that Gaelic imagination contrived and English scribes corrupted. Here are a few which I have come across in Ulster: Ballywillwill, Ballymunterhiggin, Aghayeevoge, Treantaghmucklagh. In all Ireland there are no less than 5,000 townlands beginning with ‘Bally’, forty-five of them named Ballybeg (little town).’ (Estyn Evans, Irish Folk Ways, London: Routledge 1957, p.28).

Ballybeg (II): ‘Balleybeg’ is the pseudonym given to the border town in Rosemary Harris’s MA research of 1954, called by donnan and MacFarlane ‘the most sensitive early attempt to get behind the public attitudes of Protestants and to a lesser extent Catholics in the early 1950s’ (Hastings Donnan & Graham MacFarlane, ‘Informal Social Attitudes’, in The Background to the Early Conflict, ed. John Darby (Appletree/Syracuse 1983, p.111). The authors note that Harris returned to the ‘paradox of Northern Irish life in a recent comparison between community relations in Ballybeg and ‘Patricksville’ in Southern Eire [sic] (Harris 1979, Bax, 1979), noting that ‘on the surface in the 1950s Ballybeg daily political life showed signs of considerable disunity [while] actual day-to-day life in Patricksville seemed to be replete with obvious tensions, clashes of interest and, indeed, violence; while among the population of Ballybeg there was a playing down of blatant hostility.’ (Donnan & MacFarlane, in Darby, op. cit., p.112.)

See also Edna Longley’s comment: ‘The alienation of Friel’s Ballybeg is utterly different from the post-Nationalist alienation of Tom Murphy’s Bailegangaire.’ (The Living Stream, 1994, p.182, and cf. her citation from Deane’s preface to the Selected Plays [I], supra.)

Ballybeg (III: Rosemary Harris) - see J[ohn]. O. Whyte, In Understanding Northern Ireland (OUP 1991): ‘the classic participant-observation study in Northern Ireland is Rosemary Harris’s examination of a rural area near the border which she labels “Ballybeg”. The research was conducted in the early 1950s, though the results were not upublished in book form till her work Prejudice and Tolerance in Ulster came out in 1972. The area under scrutiny was one where Catholic and Protestant farmers lived intermingled. Based on observation and interview, the study brings out how two communities could live side by side, maintain superficially courteous relations with each other, and still preserve deep suspicions and extraordinary stereotypes. The book si unfailingly lucid and perceptive, and remains one of the best ever published on Northern Ireland. most subsequent participant-observers in Northern Ireland have sought to compare Harris' findings with their own. (p.9.)

Ballybeg (IV): ‘Ballybeg’ is the name of the large housing estate in Waterford, opp. the glass factory, where the 10-yr. old Ian Swan, of Welsh parents moved to Ireland, was bullied and beaten to unconsciousness at school; the principal of St. Saviour’s Mr. Paddy Power disowning responsibility for what happens to boys on the way home if not collected; cause of national dismay, March 1995 (See Irish Times, &c.).

[ top ]

Abbey Theatre Desmond Rushe states that Brian Friel was made, in 1965, one of 25 shareholders in the Abbey Theatre, and that he has refused to give any of his plays to the Abbey. (Rushe, ‘Drama: Regional and Dublin’, in Éire-Ireland, 6, 3, Autumn 1971, p.132.)

Tyrone Guthrie Theatre (Minneapolis): Friel spent three months at Guthrie’s new theatre at Minneapolis as an observer in during early 1963, watching rehearsals of Hamlet and Chekhov’s Three Sisters. He later said: ‘those months in America gave me a sense of liberation [...] my first parole from inbred claustrophobic Ireland’, and called the experience ‘enabling’ in that it gave him ‘courage and daring to attempt things’.

25th Anniversary of Translations, celebrated in “Arts Extra”, BBC Ulster (23 Sept. 2005) [interviews with Rea, Heaney, Fintan O’Toole and Ian Hill); also, “Rattlebag” [Field Day Company 25th Anniversary Special], RTE (23 Sept. 2005), incl. interviews with Stephen Rea and Kevin Whelan].

Benedict Kiely briefly mentions Patrick Friel, father of Brian Friel, as a distinguished schoolteacher at Culmore, Omagh, before moving to Long Tower, Derry, and then to Donegal (see Drink to the Bird, Methuen 1991, p.138.)

George Steiner: Steiner’s After Babel was a significant influence on Friel. In writing that ‘a civilisation can be imprisoned in linguistic contour which no longer matches the landscape [...] of fact’ in Translations, Friel echoes phrases in that work: ‘The fixity of a lingusitic contour ... which matches only at certain, ritual, arbitrary points the changing landscape of fact’ (op. cit., p.18). Richard Kearney gives an inventory of Friel’s borrowings from Steiner in an appendix to ‘Language Play: Brian Friel and Ireland’s Verbal Theatre’, in Transitions: Narratives of Modern Irish Culture, cited by Helen Lojek in ‘Brian Friel’s Plays and George Steiner’s Linguistics: Translating the Irish’, Contemporary Literature (Spring 1994), pp.83-99; p.85.

Note also that Friel expressed dismay at the widespread reading of the play as a supposed validation of an idyllic Gaelic order.

[ top ]

Married blips: Craig Raine, reviewing Christopher Reid, ed., Letters of Ted Hughes, in Times Literary Supplement (23 Nov. 2007), relates: ‘There is an apocryphal story told of Brian Friel that illustrates the central, defining importance of writing to writers. Friel is said to have asked his wife of many years whether she would have loved him had he not been a writer at all. Of course, she reassuringly replied. It is mischievously said that the dramatist was so offended he didn’t speak to her for a month.’ (If apocryphal, why tell?: BS.)

Confusion: ‘Confusion is not an ignoble condition’ (Sel. Plays, p.446): For incidents to the oft-repeated epigram, vide Chris Morash: ‘It is not the literal past, the “facts of history” that shape us, but images of the past embodied in language.’ (Translations, quoted as epigraph to The Hungry Voice, IAP 1989, Introduction, p.15); also Fintan O’Toole, on the failure of Irish novelists to make the Booker short list: ‘[...] In literature at least, mutual incomprehension is not necessarily an ignoble condition.’ (p.9; as infra.)

Donal Donnelly, who played Gar Private in the 1964 premiere of Friel’s Philadelphia, Here I Come!, directed by Hilton Edwards at the Gaiety Theatre, was jointly nominated for a Tony Award for Best Actor with his co-star Patrick Bedford (as Gar Public) when the play transferred to Broadway. He later played Teddy in the world premiere of Faith Healer (New York 1979) and playing the brother Jack in the Broadway premiere of Dancing at Lughnasa (1991) produced by Noel Pearson, where his ‘aging, distracted, shuffling Uncle Jack’ provided some of ‘the more indelible images’ of that production according to Frank Rich of the New York Times. He also played Freddie Malins in John Houston’s film production of Joyce’s story “The Dead” and played the corrupt bishop Gilday in The Godfather III. His one-man show on G. B. Shaw (My Astonishing Self) played to acclaim in the late 1990s. In his last appearance he played the lead in Shaw’s play Don Juan in Hell, in 2006. He lived latterly with his family in Connecticut, commuting to the New York stage, and was noted for his indifference to the star system. He suffered personal tragedy when his 20-year old daughter Maryanne was killed in an equestrian accident in the mid-1980s. He died of cancer in Jan. 2010. A son Jonathan owns the Black Horse at Wrigley’s Field in Chicago. (See obituary by Colin Murphy, in Irish Independent, 9 Jan. 2010; online: accessed 18.01.2010.)

Lyric Theatre: Philadelphia, here I Come! was revived concurrently with Molly Sweeny at the Lyric Theatre, Belfast, in Feb.-March 2014 - with Gavin Drea as Gar Private, Peter Coonan as Gar Public, Des McAleer as the father SB O’Donnell, Stella McCusker as Madge, and Susan Davey as Kate Doogan, and Enda Oates as Master Boyle. Niall Cusack played Con Sweeney, Marion O’Dwyer played Aunt Lizzie and Marty Maguire played Ben Burton. Dermott Hickson was Ned and James Murphy was Tom. Andrew Flynn was the director.

Anthropometrics: For information on anthrometrics, in conjunction with its treatment in The Home Place, see A. C. Haddon & C. R. Browne, ‘The Ethnography of the Aran Islands’, County Galway, in Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy (1889-1901), Vol. 2 [1891-93], pp.768-830 - ebing a report of the Anthropometric Commission in Ireland [online at JSTOR; see also under Oscar Wilde, q.v., Notes, infra; accessed 18.05.2010].

National Portrait: a commissioned portrait of Friel by Mick O’Dea unveiled at the National Gallery Portrait Collection, Dublin, 16 July 2010 - with Friel’s son David and grandson Teddy appearing beside him before it in an Irish Times front-page photo (17 July 2010).

[ top ]