Life

| b. 17 April 1936, Ballylongford, Co. Kerry; son of Timmy & Bridie Kennelly (who met in the Ballybunnion dance-hall while he was back from America; his mother a nurse); ed. St. Ita’s College [interdenominational], Tarbert; played [Gaelic] football successfully for his parish and county as a minor, junior and senior; proceeded to TCD on long-standing scholarship founded by Anglo-Irish landlord of N. Kerry, aetat. 17 [1949]; grad. in English & French (Double 1st); worked for a time as a bus-conductor in London; proceeded to Leeds Univ., where he completed a PhD on “Modern Irish Poets and the Irish Epic” (1966), initially working under Derry Jeffares, 1962-63; took lectureship in English at TCD; issued four poetry pamphlet-books with Rudi Holzapfel; issued My Dark Fathers (1964); winner of “AE” Russell Award for Poetry, 1967; issued Selected Poems (1969); also The Crooked Cross (1963) and The Florentines (1967), novels; |

| delivered oration at grave of Frank O’Connor, 1966, later characterising him as ‘Ireland’s Ezra Pound’ in his preface to The Penguin Book of Irish Verse (1970); read with Austin Clarke and Eavan Boland at the dedication of the Yeats Memorial, St. Stephen’s Green, 26 Oct. 1967; met Peggy O’Brien at the Shelbourne Hotel, 1967, and m. 1969; a dg. [Doodle], b. 16 March 1970; appt. visiting professor at Bernard Coll., NY, and Swarthmore College, Pennsylvania, where he interviewed W. H. Auden, 15 Nov. 1971; lived in St. Alban’s Park, Sandymount [Irishtown end of Strand Rd.]; divorced, 1981; appt. to TCD Chair of Modern English, 1973; worked on Mountjoy Prison teaching programme; reviewed Heaney’s Sweeney Astray: A Version from the Irish, in New York Times Book Review, 1984 [as infra]; |

| his version of Antigone (Peacock Th., 1986), both a ‘feminist declaration’ and a ‘straight translation’ distilled from previous English versions and written in 1984, and which entered the Leaving Cert. syllabus in the 1990s; issued Cromwell (1983), a series of 160 poems on obsessive themes of Irish history with its Irish protagonist Buffún; Medea (RDS April 1988), inspired by womens’ stories overheard in a Dublin hospital in 1986; winner of Critics Special Harvey’s Award, 1988; issued new selection including early poetry as A Time for Voices (1990); coined the term ‘Protholic Cathestant’ at Kavanagh’s Yearly, Monaghan, 1990; stopped drinking after treatment for toxicity in St James’s Hospital, 1990; quadruple by-pass heart surgery in Blackrock Clinic, 1996 - and there talked with ‘the man made of rain’ in post-operational sedation; |

| issued The Book of Judas (1991), as a sequel to Cromwell, continuing the same subversive strategy; wrote a play, The Trojan Women (Peacock 1993), directed at the Peacock Theatre by Lynne Parker with Pauline McLynn as Andromache, representing both the power of women and the male fear of that power; issued Poetry My Arse (1995), revolves around poet-persona called Ace de Homer and his partner Mary Jane of somewhat Yeatsian extraction; Blood Wedding (1996), after Frederico García Lorca’s Bodas de Sangre [1933], a verse play performed in England, Autumn 1996; winner of International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award, 1996; |

|

advertised Toyota cars and financial services on television; successfully underwent triple by-pass surgery at the hands of Mr Nelligan, Oct. 1996; The Man Made of Rain (1998) is a longer poem, based on a vision experienced at the time; Äke Persson (Göteburg Univ.) hold tapes of his poetry readings, 1989-1996; winner of 1999 American Ireland Fund Literary Award, 1999; a Brendan Kennelly Summer School was held inaugurally in Ballylongford on 9-12th Aug. 2001; awarded the Wild Geese Trophy of the Ireland Fund of France, 2003; retired from TCD, Summer 2005; held fellowship at Boston College, 2007; issued Reservoir Voices (28 May 2009), following semester-long visiting professorship at Boston College, Fall 2007 - a period characterised by loneliness and depression; |

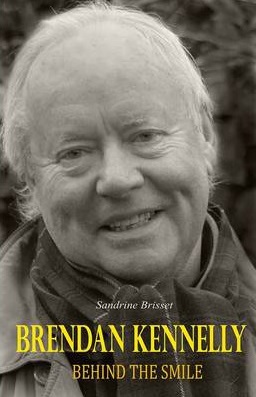

| received 2010 PEN Award for his contribution to Irish literature, 29 Jan., being presented by David Norris; The Essential Brendan Kennelly was edited by Terence Brown and Michael Longley for his 75th birthday (2011); sent video wishes from St. James’s Hospital (Dublin) to the Listowel Writers Festival, 2016; publication of a biography by Sandrine Brisset in 2013 caused a furore related to personal disclosures about his dg. Doodle [d. April 2021, aetat. 51]; Kennelly d. at Áras Mhuire Nursing Home in Listowel, Co Kerry, on 17 Oct. 2021 [aetat. 85]. DIL OCIL |

| Kerry County Arts unveiled a bust in honour of Brendan Kennelly, poet and Fellow Emeritus and former Professor of Modern Literature of English the church grounds [car park] at Ballylongford, Co. Kerry, on Friday, 21st August 2015 at 7.30pm. Professor Kennelly was in attendance on his first trip to Kerry in many years. (See English School website, TCD - online [accessed 14.09.2015]. |

[ top ]

|

[ top ]

Works| Poetry Collections | |

| Joint | |

|

|

| Solo | |

|

|

| Selections | |

|

|

| —See also listing in Poetry Archive online, or see copy attached; accessed 23.04.09]. | |

| Audio-casettes & film | |

|

|

| Plays | |

|

|

| Fiction | |

|

|

| [ top ] | |

| Criticism | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| [ top ] | |

| Edited collections | |

|

|

| Miscellaneous | |

|

|

Note: occasional contribs. incl. “Two”, a poem i.m. David Webb (TCD Fellow) , in Beyond Babel: A Journal of Undergraduate Academic Writing, ed. Niamh Tallon & Leigh Hamilton (TCD 1998 ), p.[2; as infra]. |

[ top ]

Bibliographical details| The Penguin Book of Irish Verse, ed. Brendan Kennelly (Harmondsworth: Penguin 1970; 2nd Edn. 1981) |

|

| Contents |

| Introduction; biographical notices. |

|

PART I - translated from Irish [Gaelic]: several anonymous poems trans. by Kuno Meyer; Kennelly and Frank O’Connor [22 pieces incl. The Viking Terror, Blackbird by Belfast Lough, Oisin, Caoilte, Old Woman of Beare], and James Carney; Eagan O’Rahilly [4 incl. Brightness of Brightness]; Eileen O’Leary; Anthony Raftery; Bryan Merriman. PART II - Anglo-Irish, Jonathan Swift; Oliver Goldsmith; John Philpot Curran; William Drennan; Richard Alfred Milliken; Thomas Moore; Sir Aubrey de Vere; Charles Wolfe; Jeremiah Joseph Callanan; George Darley; Eugene O’Curry [Do You Remember That Night]; James Clarence Mangan [Dark Rosaleen, O’Hussey’s Ode to the Maguire, Woman of Three Cows, Gone in the Wind, And Then No More, Lover’s Farewell, Vision of Connaught in the Thirteenth Century, The Nameless One, Siberia, Lament for the Princes of Tir-Owen and Tirconnell, Shapes and Signs, Kinkora, To Joseph Brenan, The One Mystery, To the Ingleezee Khafir, calling himself Djaun Bool Djnkinzun, time of the Barmecides, Twenty Golden years Ago]; anon., The Night that Larry was Stretched; Gerald Griffin [Aileen Aroon]; Francis Sylvester Mahoney; Edward Walsh [only Dawning of the Day]; George Fox; Samuel Ferguson [Burial of King Cormac, Cashel of Munster, Cean Dubh Deelish, Fair Hills of Ireland, Fairy Thorn, Deirdre’s Lament of the Sons of Uisnech, Lark in the Clear Air, Lament for the Death of Thomas Davis, Vengeance of the Welshmen of Tirawley]; aubrey de Vere; Thomas Davis [only Lament for the Death of Eaoghan ruadh O’Neill]; William McBurney [The Croppy Boy]; Arthur G. Geoghegan [After Aughrim]; Lady Wilde [The Famine Years]; John Kells Ingram [Memory of the Dead]; Michael Joseph McCann [O’Donnell Abu]; Thomas Caulfield Irwin [four sonnets]; William Allingham; Thomas D’Arcy McGee [The Celts]; John Todhunter; Edward Dowden; John Boyle O’Reilly; Arthur O’Shaugnessy; Emily Lawless; Alfred Percival Graves; William Larminie; John Keegan Casey; Fanny Parnell; Oscar Wilde; T. W. Rolleston; John Synge; Thomas MacDonagh; Patrick Pearse [I am Ireland, Renunciation, The Mother, The Fool, The Rebel, Christmas 1915]; Joseph Plunkett; Francis Ledwidge [Wife of Lew, June, The Coming Poet, Thomas MacDonagh, The Blackbirds, Ireland]. PART III - Yeats and After: W. B. Yeats [only To Ireland in the Coming tims, Sept. 1913, The Statues]; George Russell [only On Behalf of Some Irishmen Not followers of Tradition]; Oliver St John Gogarty; Seamus O’Sullivan; Padraic Colum; James Joyce [Gas from a Burner]; James Stephens [A Glass of Beer]; Austin Clarke; Monk Gibbon; F. R. Higgins [Father and son];; R. N. D. Wilson [Enemies]; Patrick MacDonogh [The Widow of Drynam]; Ewart Milne [Ballad of An Orphan]; C. Day Lewis [remembering Con Markievicz; Padraic Fallon [Field Observation]; Bryan Guinness; Patrick Kavanagh; Samuel Beckett [Poem]; John Hewitt [The Glens]; Louis MacNeice [Valediction]; Denis Devlin [The Colours of Love]; Robert Farren [The Mason]; W. R. Rodgers [The Net, Home Thoughts from Abroad]; W. B. Stanford; Donagh MacDonagh; Sigerson Clifford [Ballad of the Tinker’s Wife]; Valentine Iremonger [Icarus]; Kevin Faller; Roy McFadden; Padraic Fiacc; Anthony Cronin [For a Father]; Jerome Kiely [Lizard]; Eugene R. Watters [from Weekend of Dermot and Grace]; Pearse Hutchinson [Look, No Hands];Richard Kell; Richard Murphy [The Poet of the Island]; John B. Keane; Ulick O’Connor [Oscar Wilde]; Basil Payne; Thomas Kinsella [Downstream II]; John Montague; Sean Lucy; Richard Weber; James Simmons [Art and Reality]; James Liddy [In Memory of Bernard Berenson; Rivers Carew [Catching Trout]; James McAuley [Stella]; Desmond O’Grady [Homecoming]; Kennelly [My Dark Fathers]; Rudi Holzapfel [The Employee]; Seamus Heaney [At a Potato Digging]; Timothy Brownlow [Leaving Inishmore; Michael Hartnett [Mo Grá Thu]; Derek Mahon [In Carrowdore Churchyard]; Eilean ni Chuilleanáin; Eaven Boland [New Territory]; Tom McGurk [Big Ned]. Acknowledgements and index of titles and first lines. |

| —Retrieved from Wikipedia entry on Penguin Poetry Anthologies - online (10.05.2011). |

| [ A fuller account of the contents of this volume is given in the Bibliography > Anthologies pages of Ricorso - as attached. ] |

[ top ]

Landmarks of Irish Drama, introduced by Brendan Kennelly (London: Methuen 1988), CONTENTS: Introduction, vii-xliv; G. B. Shaw, John Bull’s Other Island; Synge, Playboy; W. B. Yeats, On Baile’s Strand; Seán O’Casey, The Silver Tassie; Denis Johnston, The Old Lady Says “No!”; Samuel Beckett, All That Fall; Brendan Behan, The Quare Fellow [an appendix to which includes 1 page of the Gaelic version]. Bibliography incls. such titles as Lady Gregory, Our Irish Theatre (1973 edn.); O’Casey, Autobiography (espec. Inisfallen, 1940); Nicholas Grene, Shaw: A Critical View (1984); Peter Ure, Yeats the Playwright (1963); Grene, Synge: A Critical Study of the Plays (1975); James Simmons, Sean O’Casey (1983); Joseph Ronsley, [ed.,] Denis Johnston, A Retrospective (1981).

Åke Persson, ed., Journey into Joy: Selected Prose (Newcastle: Bloodaxe 1994), 271pp.; CONTENTS: Kennelly, Preface [9]; Persson, Introduction [11]; Poetry and Violence [23]; A View of Irish Poetry, 1. Irish Poetry to Yeats [46; see extract]; 2. Irish Poetry Since Yeats [55; see extract]; A View of Irish Drama [72]; The Poetry of Joseph Plunkett [103]; Patrick Kavanagh’s Comic Vision [109; see under Kavanagh, as supra]; Derek Mahon’s Humane Perspective [127; see under Mahon, as infra]; Louis MacNeice: An Irish Outsider [136]; George Moore’s Lonely Voices: A Study of his Short Stories [145]; The Heroic Ideal in Yeats’s Cuchulain Plays [162]; Austin Clarke and the Epic Poem [170]; Satire in Flann O’Brien’s The Poor Mouth [182; see under O’Brien, as infra]; The Little Monasteries: Frank O’Connor as a Poet [198]; Seán O’Casey’s Journey into Joyce [209]; James Joyce’s Humanism [217]; W. B. Yeats: An Experiment in Living [231]. Editor’s Note, 248; Notes, 249; Acknowledgements, 265; Index, 266.

‘Patrick Kavanagh ’, in Ariel (July 1970), pp.7-28 [available at Ariel Archive online - accessed 21.05.2011]; rep. in Irish Poetry in English, ed. Seán Lucy [The Thomas Davis Lectures on Anglo-Irish Poetry] (Cork & Dublin: Mercier Press 1973), pp.159-84 [Chap. XI; see under Patrick Kavanagh, supra]; rep. as ‘Patrick Kavanagh’s Comic Vision’, in Åke Persson, ed., Journey into Joy: Selected Prose (Newcastle: Bloodaxe 1994), pp.109-26. [See also full-text copy in RICORSO Library, “Critical Classics”, via index or direct.]

[ top ]

Criticism| Monographs & Collections |

| Articles & Reviews |

|

|

See numerous others under Commentary - infra. |

| See also |

|

| [See also remarks on in Julia O’Faolain, ‘The Furies of Irish Fiction’, in Graph (Spring 1998) - as attached.] |

|

| Port. by Sandrine Brisset (2013) |

| See collection of the poems of Brendan Kennelly at Anglisztika, Univ. of Hungary > Irish studies - online; accessed 16.03.2021; defunct 25.05.2023. |

[ top

Bibliographical details

Richard Pine, ed., Dark Fathers into Light: Brendan Kennelly [Bloodaxe Critical Anthologies 2] (Bloodaxe 1994), 224pp. [contribs. Gabriel Fitzmaurice (life), Augustine Martin (early work), Terence Brown (the novels), Gerald Dawe (poetry), Jonathan Allison (on Cromwell), Anthony Roche (on The Book of Judas), Kathleen McCracken (plays for women), Åke Persson (his criticism); interview by Pine; bibliography incls. works on Kennelly and his broadcasts.]

John McDonagh, Brendan Kennelly: A Host of Ghosts (Dublin: Liffey Press 2004), 170pp. [Chapters: Getting up Early; Old Loyalties: The Boats Are Home; Spilling Selves; Cromwell; The Chaos of Mind; Medea; Following the Judasvoice; Blitzophrenia: Brendan Kennelly’s Postcolonial Vision.]

Internet link: Lynn McBrien [interview], CCN Student News ( January 2, 2001 ) [go online or see attached].

[ top ]

| Terence Brown Geert Lernout Richard Pine Patrick O’Sullivan Alan Titley |

Tom Herron Des O’Rawe David Butler John MacDonagh John Greening |

Fiona McCann Mark Hederman Paul Perry |

Terence Brown, ‘British Ireland’, in Edna Longley, ed., Culture in Ireland, Diversity or Division (QUB/ISS 1991), pp.72-83, has written: ‘Similarly, at a more popular level, in a work of art that seemed to express the folklore and mythology of Irish nationalism at its most instinctive and visceral level, Brendan Kennelly’s Cromwell (1983), our contemporary imbroglio is symbolised as a permanent destructive conversation between the English Lord Protector and an Irish Buffún who cannot escape from the inauthentic definitions of himself

thrust upon him by the English tyrant.’ (p.73).

Terence Brown & Michael Longley, foreword to The Essential Brendan Kennelly (2010): ‘Brendan Kennelly is a poet of rare gifts, who at all stages of his career has written distinctive, memorable and powerful poems. We hope that this selection will allow readers to appreciate anew, or for the first time, a body of work that ranges from tender lyricism to the bleakest despair at the human condition, from bawdily comic narrative to the pleasingly epigrammatic squib, from mythic consciousness to social satire ... Yet each literary mode - the lyrical and its obverse, a reductively satirirc assault on "the poetic" - shares what has seemed the basis of all of Kennelly’s poetry: a quest for authenticity of emotion undertaken with high moral intent. In each, as Beckett said of the painter Jack Yeats, the poet “stakes his being”’. |

| —Quoted on the Bloodaxe website - online [accessed 24.02.2011] |

Geert Lernout, ed., The Crows Behind the Plough: History and Violence in Anglo-Irish Poetry and Drama (Amsterdam: Rodopi 1991): ‘This ludic Republic has its poet laureate - “the robust, every smiling Kerryman with a touch of genius” - Brendan Kennelly. It is of little consequence if Kennelly himself identifies with the assigned role. If he did not exist it would be necessary to invent him, so strong is the lure of the merry Ireland myth.’ (Lernout, Intro., p.12; quoting from [interview article] ‘Brendan Kennelly: All things to all men, and a proper Irishman too’, in The Irish Times, 26 June 1989).

Richard Pine, reviewing of The Book of Judas, notes early lyrical collections, My Dark Fathers (1964), Love Cry (1972) and A Kind of Trust (1975); remarks that ‘personal crises turned Kennelly into a more publicly resolute, gritty and yet carefree writer. Moloney Up and At It (1984) followed by controversial Cromwell (1983), where the full meaning of loyalty and betrayal, of allegiance and divorce, was played out within the poet’s imagination ... against the background of public history, atrocity, suspicion and deviance.’ Further, in the introduction to the Book of Judas, Kennelly explains that in Cromwell ‘I tried to open my mind, heart and imagination to the full, fascinating complexity of a man I was from childhood taught, quite simply, to hate. A learned hate is hard to unlearn.’ Pine continues: ‘As he told me in a Q&A in 1989, writing the Book of Judas was an attempt to confront our capacity for betrayal and for recognising that capacity as the concomitant of life. Kennelly brings Judas ... into the heart of Irish life, into politics, the family, the love-bed, the courts of law, the market place, and shows how indelibley present he is in all our transactions, ‘the scapegoat, critics of self and society, throws chronological time out the window. Before our ancestors arrived on the scene, he was. After the unborn have ceased to exist, he’ll be.’ The book of 365pp. contains almost 600 poems in 12 sections. ‘I have never seen him and I have never seen / Anyone but him.’ Versions of Antigone, Medea, and The Trojan Women. The Judas Book ends, ‘I would ask, to begin with, what became of the true thing. / And after all, well, anything might happen. / A can even imagine a poet starting to sing / Inna way I haven’t heard for a long time. / If the song comes right, the true thing may find a name / Singing to me of who, and why, I am.’ (Pine, in Irish Literary Supplement, Fall 1992).

Patrick O’Sullivan, reviewing Journey Into Joy, Selected Prose, ed., Ake Persson, and Dark Fathers Into Light, ed. Richard Pine, finds the Kennelly asserting the interdependence of poetry and the poet’s life (‘tautologous procedures, noble life and artistic achievement’) in relation to his favorites, Yeats, O’Casey, Clarke, Kavanagh; and comments ‘fidelity to unloveliness, psychological or social, is acutely problematic, and tends towards an aesthetic of self-abolition.’ Of the critical collection, he finds the adulation too supine, for there are not dissenting voices; essays by Terence Brown and Augustine Martin singled out for commendation; further contributions by Anthony Roche, among others. (Diaspora Irish studies e-list.)

Alan Titley, review of Poetry My Arse (Bloodaxe 1995), noticed by in Books Ireland (Nov. 1995), p.304; quotes introduction by Kennelly suggesting that the ‘trick is to parody the parody’, but doubts that the ‘self-professed cute hoor’ from Kerry brings it off, falling into self-indulgence instead. Further, ‘if this is satire or parody, it is done with buckshot, sledgehammer and stink-bomb ...’.

[ top ]

Tom Herron [Aberdeen], Poetry My Arse (Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Bloodaxe 1995), in Irish Studies Review (Spring 1996), pp.53-54: the question of poetry’s efficacy ... ramify beyond the narrative of poet Ace de Horner’s troubled relationships with poetry, with Janey Mary, poetry’s fiercest critics, with the city, with the loss of sight, with sex, with politics, with terrorism, with death, and with his loveable pitbull (won in Ireland’s first and only dog lotto), Kanooce; quotes Kennelly’s contention that poetry and gossip share much: ‘they are both born of hunger; mental, emotional, intellectual, physical hunger of various kinds. They both, when the are “good”, have a special kind of energy, a kick, that’s pretty hard to equal almost anywhere else. They are both predatory [and] enjoy a certain amount of detachment ... that enables them to dispense with their individual versions of local lies and cosmic truths with a perfectly desirable blend of passion and style.’ Compares ‘Imitation’, which is voiced in a ‘shithouse at the back of a National School / in a remote part of rural Ireland’, with Mahon’s ‘A Disused Shed in Co. Wexford’, as a discrete history of loss, ridiculous and brilliant.

Des O’Rawe, review of Antigone, with Derek Mahon’s Phaedra (1996), in Irish Review, Winter/Spring 1997), notes iconoclastic and impish lyrical voice’, exemplified by the translation of the stasimon (‘Love, you are the object of our lives ...’), and comments: ‘One might be forgiven for suggesting that Kennelly’s talents might be better suited to translating Aristophanes than Sophocles. […] (q.p.)

David Butler, ‘A jester of barbed jibes’, review of Familiar Strangers: New & Selected Poems 1960-2004 (Bloodaxe), and John McDonagh, Brendan Kennelly: A Host of Ghosts (Liffey Press, 170pp., in The Irish Times (25 June 2004) [Weekend], writes: ‘In a 1990 interview with Richard Pine, published in The Irish Literary Supplement, the poet suggests that “the flaws in my writing, which are considerable, have to do with spontaneity”, while a more recent interview with Arminta Wallace [The Irish Times 22 May 2004) posits the idea of poetry as a form of gossip. Neither comment sits well with a critical orthodoxy that puts a premium on the highly crafted and allusive, often at the expense of intelligibility. Kennelly instead positions himself as something of a court-jester at the banquet, and it is characteristic that the central consciousness of his Cromwell sequence should bear the name of Buffún. As with Lear’s Fool, however, Kennelly’s jibes are barbed.’ Regards New & Selected Poems 1960-2004 as an unusual résumé of a lifetime’s outputin that it orders the poems not by in a ‘loosely thematic manner’ rather than chronologically. ‘To the extent that Kennelly views his own poetic mission as being a conduit for voices, in particular those of the marginalised and vilified, the strategy is largely successful. Within his own sequences, historical personages converse freely with the living and with the imaginary, and are reborn under a number of guises.’ Butler argues that the title, Familiar Strangers, suggests ‘the encounter between poems that would not normally be juxtaposed on facing pages, and the encounter between heavily anthologised poems such as “My Dark Fathers”, “The Pig-killer” and”’Bread”, and a number of previously uncollected poems.’ Further: ‘Such themes as dominate - the loss of language; the harsher realities of rural and urban life; cyclical violence in all its manifestations from the historical to the sexual and quotidian - place Kennelly firmly in the tradition of an older generation of poets, notably Austin Clarke, Patrick Kavanagh, John Montague and Michael Hartnett. His bantering, irreverent, multi-vocal tone, however, is more likely to suggest comparison with several post-moderns at their more playful - Ciaran Carson, say, or Paul Muldoon - though one would have to say that the ludic manipulations of language that these employ are far more sophisticated. No doubt Kennelly is content to be a jester who wears both caps and thereby avoids easy classification.’ Commends MacDonagh’s critique as jargon-free.

John MacDonagh, ‘“Blitzophrenia”: Brendan Kennelly’s Post-Colonial Vision’, in Irish University Review (Autumn/Winter 2003), pp.322-36: ‘It can also be argued that Kennelly’s poetics, exemplified in Cromwell, offer a far more exciting and vivid picture of the manifestations of postcolonial theory than the theory itself. Glenn Hooper notes the importance and influence of Homi K. Bhabha’s theoretical interventions and refinements of post-colonial theory in the 1990s; Kennelly, however, was exploring similar territory almost a decade previously. In his essay “DissemiNation” for example, Bhabha states that the “political unity of the nation” is predicated upon the formation of “a signifying space that is archaic and mythical” whereas in the first poem of Cromwell, Buffun, the central figure, observes that his concept of national identity is built upon “a mountain of indignant legends, bizarre history, demented rumours and obscene folklore” (p.15), all recognizable constituent elements of national mythologies. Kennelly’s eclectic and often surreal exploration of the role of Oliver Cromwell in [323] the formation of the Irish psyche takes him precisely to the liminal spaces Bhabha identifies as the sites of putative national signification.’ (pp.323-24.)

John MacDonagh, ‘“Tore Down à la Rimbaud”: Brendan Kennelly and the French Connection’, in Reinventing Ireland Through a French Prism, ed. Eamon Maher, et al. [Studies in Franco-Irish Relations] (Frankfurt: Peter Lang 2007), pp.181-94: ‘[…] Unsurprisingly, Patrick Kavanagh (1904-67) is a seminal figure […]. There are strong parallels between Kennelly’s unromanticised, spare and often harsh portrayal of his community and the poetry of Kavanagh in the early 1940s, both clearly displaying a natural empathy with and deep understanding of their respective birthplaces, although the poetic desire to see beneath and beyond the surface of an apparantly idyllic rural existence soon emerges. It is not surprising that Kennelly recalls writing out by hand Kavanagh’s excoriating 1942 epic The Great Hunger in the National Library in Dublin when a student in Trinity College in the 1950s, an early indication of his fondness for Irish interpretations of the epic form which were to prove such a successful poetic vehicle later in his career. What particularly attracted Kennelly to Kavanagh was the latter’s debunking of a pervasive rural mythology, a literary and cultural hangover from the revivalist movement of the late 19th/early 20th centuries as well as a sharp observation of the ordinary events of daily life. Kennelly notes Kavanagh’s wonder at “the startling significance and beauty inherent in casual things” and there can be little doubt that Kavanagh’s poetry liberated a great many succeeding poets into writing about the commonplace [...; see further under Kavanagh, supra.] However, Kennelly work is more complex than a mere rendering of the often difficult circumstances of his rural upbringing, and it is here that the other influences begin to be heard.’ (p.182.) ‘Although he is probably better known for his rural poems, Kennelly is an important poetic chronicler of Dublin, where he has lived for forty years. For example, his 1995 epic sequence Poetry My Arse foregrounds a Dublin packed with begrudgers, chancers, spoofers, liars and hyocrites, and is undoubtedly one of the funniest, sharply observed and overlooed portraits of, as Eliot put it, “the sordid life of the metropolis”.’ (Ibid., p.187.) The other influences on Kennelly names are Ginsberg, Baudelaire and Rimbaud.

John Greening, ‘Guff and Muscle’, review of Brendan Kennelly, Familiar Strangers: New and Selected Poems, in Times Literary Supplement ( 22 April 2005): ‘[…] Sometimes his emotions lead him to be prolix and self-indulgent, or to make the kind of empty gestures we find in “Moments When the Light”, which describes but does not re-enact a vision. Yet he can make a simple observation effectively (”Pram”, “The Big House”), and is succinct in his savagery in the many sonnets, about the casual slaughter of animals, about human atrocity. Violence threads and marbles this book: of childhood and school life, in love, in war, throughout Irish history - the extracts from Cromwell (1983-87) reminding us just how many taboos that volume broke. One of the virtues of this “New and Selected” is that it puts a sonnet like “Nails” in a different context, so that the link between crucifixion and nail-bomb is still in our minds as we read the sonnet next to it, “Innocent”, about a child pulling wings off a fly. The disadvantage of the chocolate-box arrangement is, of course, that some of the early poems show their age and the entirely different registers of, say, “James Joyce’s Death Mask” and the brilliant Swiftian satire of “The Dinner” shift the “drunkenness of things being various” [vide Louis MacNeice] towards disorientation. / Because he writes so much, Kennelly seems permanently alert to the world, always ready to snatch his perception and turn it to verse - a conversation, an overheard remark, an encounter. Inevitably, this means that much of his work lacks a more concentrated and repeatable magic. “Dream of a Black Fox”, one of his touchstones, is good, but hardly a Thought-Fox, still less a “shape with lion body and the head of a man”. Kennelly is always looking for (or lamenting the lack of) the visionary, a Muse, some unpriestly guide to the underworld: his Virgil (”the man made of rain”) has as much of the craic as any other Dubliner, and his “glimmering girl” is most convincing when she is flesh and blood. […].’ (p.22; see full-text copy in RICORSO > Library > Reviews - via index or as attached.]

[ top ]

Fiona McCann, interview, ‘A Reservoir of Poetic Inspiration’ [interview-article], in The Irish Times (23 May 2009), Weekend, p.7 [with port]; relates his arrival at TCD on scholarship founded by N. Kerry landlord for the education of the peasantry, aetat. 17; ‘Sure, I didn’t knwo what they were saying, and they didn’t know what I was saying either’; met Patrick Kavanagh who was broke and seemed to want help, ‘maybe to get him a room in the college [but] I didn ‘t.’ Contradicted W. H. Auden’s famous assertion that ‘poetry makes nothing happen’ to his face at Pennsylvania, and supplied Auden with whiskey at a boring dinner (‘If you’re from Ireland, you must have whiskey on your person’), receiving three bottles of Jack Daniels on the following morning in return; three grand-daughters; issued Reservoir Voices, based on inner voyage during lonely and depressing period as visitor at Boston College, 2007; occas. called on by Charles Haughey to talk poetry at Kinsealy; quotes poem of his which is a favourite of Meryl Streep, written at the time of by-pass [coronary] surgery: ‘Begin again to the summoning of birds / Though we live in a world that dreams of ending / that always seems about to give in / something that will not acknowlege conclusion / insists that we forever begin.’ [End.]

Mark Patrick Hederman, review of Susan Gubar, Judas: A Biography (NY: Norton), in The Irish Times (22 Aug. 2009), Weekend: ‘Using a somewhat implausible, yet nonetheless thought-provoking, juxtaposition between The Book of Judas and Althusser’s 1996 prestentation of ISAs (ideological state apparatuses) she reads Kennelly as a prophetic voice describing Christy Hannity, as it emerged in Ireland during the 20th Century, as an institutional embodiment of the spirit of Judas rather than the spirit of Jesus. / Everywhere in our churches, our schools, our banks, our politics, our legal, family, trade-union, communications and cultural systems, the Judas-effect of greed, avarice and betrayal is more in evidence, as recognisable hall-marks, than is the ethos of the Sermon on the Mount. It is a sobering thought, and this book makes for sobering reading.’ (Irish Times, p.13, with author-note: Hederman is abbot of Glenstal Abbey, Limerick; his book Walkabout, published by Columba Press, contains an alternative reading of The Book of Judas and some pertinent correspondence with Brendan Kennelly.

Paul Perry, ‘Accepting the gift’, review of The Essential Brendan Kennelly, in The Irish Times, 7 May 2011, Weekend Review, p.11: in riposte to ‘cries of too much, too much by many critics’: ‘I'd suggest this is a criticism we will hear less of as the years pass. The great Anton Chekhov wrote up to 800 short stories, and nobody now says he wrote too much. That is why the selection of a writer’s work is so important. / One of the first poems in The Essential Brendan Kennelly is “The Gift”, in which he writes: “It was a gift that took me unawares / And I accepted it.” The acceptance of the gift of poetry, and the joy and pain it took and takes to accept such a gift, is worth honouring. Irish poetry would be unrecognisable without Kennelly’s vital contribution. A lifelong vocation is captured in the final poem, from Reservoir Voices, of this celebratory collection: “I look back, up. Where is the hill of shadows? Grey clouds cover it. Where is the orphan now? / And who is the person shaping to write me down? / Words are wild creatures. Fly them home.”’ Also mentions as especially memorable “Begin”; “The Kiss”; “My Dark Fathers”; “Dream of a Black Fox” [reads as an indelible image of totemic fear]; “Let it Go. I see You Dancing, Father” [echoes of Patrick Kavanagh]; “Poem from a Three-Year-Old”. Quotes “Proof” [as in Quotations, infra], here called his haunting poem, and speaks of his captivating voice. Remarks that the poems are given chronologically but only identified with their original collections in the ‘sequences’ or the Bloodaxe-published books. (Available online; accessed 02.08.2011.)

Bruce Stewart [draft-essay on Famine in Irish literature, 2021]: ‘The sheer pathos of the Famine has been powerfully conveyed in a modern poem by Brendan Kennelly (a much-loved professor of English in Trinity College, Dublin) who encapsulates the national feeling under the title of “My Dark Fathers”: ‘dark’ because we hardly know who they were in any personal sense. Indeed, it is the impersonality of their suffering that guarantees the strength of identification. Benedict Anderson tells us that a nation embodies the idea of a ‘imagined community ’ [ref.] spanning distances in time and space such that we identify with people we have never met and whose conditions are wildly at variance from our own because ‘the nation is always conceived as a deep, horizontal comradeship. ’ He goes on: ‘Ultimately it is this fraternity which makes it possible, over the past two centuries, for so many millions of people, not so much to kill, as willing to die for such limited imaginings. ’ Kennelly ’s poem reads in part:

Although some touches reveal the academic ingredients in the poem - for instance, ‘everywhere a going down of light’, with its close echo of Edward Thomas - the main impact is a faithful memorial of kinship rather than a mourning for individuals who suffered death by starvation and infection. It is apodictic from the start that the ‘giant grief’ was part of a ‘night of wrong’ is easily identifiable as British misrule in Ireland: if you don’t know that, you shouldn’t be reading the poem. The anonymity of the victims and the ‘darkness and shame’ which the poet perversely yet magnificently celebrates speak of communal identification rather than personal empathy. Less happily, the ‘moping’ absence mentioned soon afterwards - and without any apparent syntactical connection - triggers an accidentally comic note in view of the sarcastic term MOPE which Irish revisionist historians have bestowed on their famine-bemoaning confrères - letters that stand for ‘the most oppressed people ever’. In such ways, the Famine Dead have become part of the currency of national feeling, thus bearing witness to the fact that the majoritarian killer in Irish history is deemed to be genetically associated with the villain of colonial history in that land: England. The demographic proof of this contention (as expressed in Famine deaths) seems so glaringly obvious to all that the economic theory involved never yet been tested. Could the British have stopped the Famine and how? Was that “how” within the remit of any British government? Irish historians tend to think that those we are sceptical about the ability of 19th century government to intervene on such a scale is really part of an ideological privileging of the Free Market - laissez-faire, Thatcherism and whatever you’re having. Famines were far from rare in Ireland and internecine war as the norm in much of its pre-British history. We have yet to see what the future brings. |

|||

| Ref.: Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism [rev. edn.] (London: Verso 1983), pp.6-7 . |

Brian Lynch, review of Familiar Strangers - Selected Poems of Brendan Kennelly (2004):

“Energy alone is eternal delight.” William Blake said that, but he didn’t know Brendan Kennelly. For him, on the evidence of this book, delight is a dark force, indistinguishable from fury, a rage to compose reality and verse unleashed with such vehemence that it displaces itself. This is a most unusual trait in a writer if not in a man - it is pretty much always found in a male poet’s world - and it deserves attention, not least because it goes against the grain of contemporary thinking about poetry and, indirectly, has important things to say about the way we Irish are.

Yeats said, “Sing whatever is well made.’ Patrick Kavanagh wanted, when he wanted anything, to strike “a true note on a slack string”. Kennelly, by contrast, beats on a bodhrán, at once loose and tightly stretched, made out of his own skin. Self is a primitive instrument, although when it comes down to it, self is near enough all any poet has got to start with, and what he or she learns or acquires later - skill with form, knowledge, wisdom, a sense of the tradition - only serves to grease the vehicle’s wheels or add a gloss to the original shine.

In Kennelly’s case, however, one often gets the impression that both the self and the skills are fundamentally provisional - the flimsiness of the latter makes filmy the very existence of the former. Is there really a person, as opposed to a persona, behind all this outpouring?

Technically, the answer is an indistinct, uncertain, uneasy yes-no-and-maybe. In the first place, which is also, unfortunately, the last place as far as criticism is concerned, much of what appears in this massive book - it’s a Selected Poems rather in the way that a bucket of water from the Shannon is the Shannon - is not verse at all. Prose cut ragged on the right-hand side, while it makes for quick and easy reading, does not suit the memory, and memorability is still the stuff of poetry. There are good single poems in this collection, quite a few of them too, but it is hard to separate the bright beasts from the rest, “a dull herd in stupefying weather”, which constitutes the work as a poetic whole.

But these are technical judgements. The human answer to the above question is a decided “yes”. On the other hand, how one defines and, if one is so minded, judges this particular human comes down to one’s own abilities as a reader of character. In doing so, the media view of Kennelly is of absolutely no use: the idea of him, for instance, as the Kerry pixie of poetry misunderstands all those words (Kerry not least). But there is no need to turn to the media for assistance; all the necessary evidence is near at hand, his “dark materials”, and when one makes a single adjustment to one’s expectations the task of reading becomes richly engrossing.

The adjustment is this: one should read Kennelly not as if he is a poet but a novelist. He is, moreover, a novelist who has but one character, himself. He says it directly in (suitably enough) a prose poem called “Islandman”: “The use of a persona in poetry is not a refusal to confront and explore the self but a method of extending it, procuring for it a more imaginative and enriching breathing space by driving out the demons of embarrassment and inhibition and some, at least, of the more crippling forms of shyness and sensitivity.”

There is violent magic here: the stranger makes himself known; the familiar, like an unruly and frightened child, makes strange. The squalling is unmediated - and mediation is, after all, one of the essential functions of poetry - but as a result the communication is raw, vigorous and - unusual word - historical. In our era, the violence and irreconciliability of Irish character have presented us with Kennelly, a tormented but thereby truthful witness. [With the author’s permission; first printed in Irish Independent, 2 Oct. 2004 - available online; accessed 21.10.2021.]

[ top ]

|

|

|

|

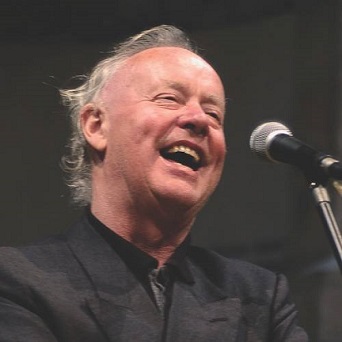

| [ Top: Brendan in Trinity (Front Square), by David Conaghy; Bottom Left: Bloodaxe Books ] |

“My Dark Fathers”: ‘My dark fathers lived the intolerable day / Committed always to the night of wrong, / Stiffened at the heartstone, the woman lay, / Perished feet nailed to her man’s breastbone. / Grim houses beckoned in the swelling gloom / Of Munster fields where the Atlantic night / Fettered the child within the pit of doom / And everywhere a going down of light. // And yet upon the sandy Kerry shore / The woman once had danced at ebbing tide / Because she loved flute-music and still more / Because a lady wondered at the pride / Of one so humble. That was long before / The green plant withered by an evil chance; / When winds of hunger howled at every door / She heard the music dwindle and forgot the dance. // Such mercy as the wolf receives was hers / Whose dance became a rhythm of the grace, / Achieved beneath the thorny savage furze / That yellowed fiercely in a mountain cave. / Immune to pity, she, whose crime was love, / Crouched, shivered, searched the threatening sky, / Discovered ready signs, compelled to move / Her to innocent appalling cry. // Skeletoned in darkness, my dark fathers lay / Unknown, and could not understand / The giant grief that trampled night and day / The awful absence moping through the land. / Upon the headland, the encroaching sea / Left sand that hardened after tides of Spring, / No dancing feet disturbed its symmetry / And those who loved good music ceased to sing. // Since every moment of the clock / Accumulares to form a final name, / Since I am come of Kerry clay and rock, / I celebrate the darkness and the shome / That could compel a man to turn his face / Againt the wall, withdrawn from light so strong / And undeceiving, spancelled in a place / Of unapplauding hands and broken song.’ (My Dark Fathers, 1964; see photo-version as attached. See also Kennelly’s account of the origin of the poem - infra.]

| Autograph account of the origins of his poem “My Dark Fathers”: |

|

| —Introduction to Selected Poems (q. edn.); for full extract and source, see attached. |

Cromwell (1983), Introduction: ‘Because of history, an Irish poet, to realise himself, must turn the full attention of his imagination to the English tradition. An English poet committed to the same task need hardly give the smallest thought to things Irish.’ (Quoted in Edna Longley, ‘Poetic Forms and Social Malformations’, in The Living Stream: Literature and Revisionism in Ireland, Newcastle-Upon-Tyne: Bloodaxe 1994, pp.197-226, p.198.) Further: ‘I remember thinking, as the blood escaped / Into the earth, that Oliver did what Oliver did. / So did the butcher. So do I. So do we all.’ (p.147; quoted in John McDonagh, ‘”Blitzophrenia”: Brendan Kennelly’s Post-Colonial Vision’, in Irish University Review, Autumn/Winter 2003, p.333.

| “Begin” | |

|

Begin to the loneliness that cannot end since it perhaps is what makes us begin, begin to wonder at unknown faces at crying birds in the sudden rain at branches stark in the willing sunlight at seagulls foraging for bread at couples sharing a sunny secret alone together while making good. Though we live in a world that dreams of ending that always seems about to give in something that will not acknowledge conclusion insists that we forever begin. |

|

|

[ top ]

Antigone (1986): Antigone (to Creon), ‘Yet never forget the possible difference / Of that other world of the gods. / Thinking of difference there / May make us different here. / Creon, you fear the thought of difference.’ (Sophocles’ Antigone: A New Version (Bloodeaxe 1986, p.24.) Ismene, ‘Remember this, Antigone: / You and I were born women. / We must not go against men. / I say / We must not go against men. / We are ruled by those who are stronger / we must obey / Even when we do not believe / In our obedience. / We must obey in spite of disbelief. / That is why I will obey Creon.’ (Kennelly, Sophocles’ Antigone, Bloodaxe Edn. 1996, p.9.) Antigone: ‘Mock me if you will. / I do not doubt that you are able. / You are used to flattering men. / But I am a woman / And must go my way alone. / You know all about me / You know all about power / You know all about money. /But you know nothing of women. / What man / Knows anything about women?’ (p.35; the foregoing quoted in Loredana Salis, ‘”So Greek with Consequence”: Classical Tragedy in Contemporary Irish Drama’, PhD Diss., UUC, 2005.)

The Book of Judas (1991): ‘When I was interviewed for my job as an apostle / I thought Jesus’s questions were rather prickly, / Like sitting on thistles.’ Judas and Jesus swap roles to see what it feels like. ‘Turning the notion of betrayal on its head, the book depicts Judas as a scapegoat in the design of Christ’s martyrdom’. See also the Introduction: ‘I tried to open my mind, heart and imagination to the full, fascinating complexity of a man I was from childhood taught, quite simply, to hate. A learned hate is hard to unlearn.’ (Quoted Alison O’Malley-Younger, review of John MacDonagh, Brendan Kennelly: A Host of Ghost, in Diaspora E-List [online] 3 Sept. 2004.)

| “The Gift” | |

| It came slowly. Afraid of insufficient self-content Or some inherent weakness in itself Small and hesitant Like children at the tops of stairs It came through shops, rooms, temples, Streets, places that were badly-lit. It was a gift that took me unawares And I accepted it. |

|

| —Given on Facebook by Peter Quinn (09.10.2106). | |

Breathing-Spaces (1993), Preface: ‘“Entering into” such … mythical monsters [Cromwell and Judas], is an effective way to stir that mobile, boggy swamp of egotism known as the self … Engagement with such figures provides a breathing space for the imagination forces to live into the selfswamp.’ (Quoted in Åke Persson, review, in Poetry Ireland, Winter 1992-93, pp.59-75, p.60.)

“Two” (i.m. David Webb): ‘You're a man in two places, David: / under a cherrytree one April morning / flowering something fierce after a bad / Winter and a nothingtowritehomeabout Spring. // Head down at first, suddenly you look up / into a blaze of light and blossom, / stand there several minutes outside the trap / of time, pondering. Slowly, you move on // into a January evening, north end of the Rubrics; / “Coldest corner of Ireland, days like this, / cold cutting into marrow and heart”: // killed in Oxford, buried back o’ the Chapel, / cherryblossom warming the threat of ice / as if art lit science, science pleasured art.’ (in Beyond Babel: A Journal of Undergraduate Academic Writing, ed. Niamh Tallon & Leigh Hamilton, TCD 1998, p.[2].)

“Proof”: “The fox eats its own leg in the trap / To go free. As it limps through the grass / The earth itself appears to bleed. / When the morning light comes up / Who knows what suffering midnight was? / Proof is what I do not need.” (Quoted in Paul Perry, review of The Essential Brendan Kennelly, in The Irish Times, 7 May 2011, Weekend Review, p.11.)

[ top ]

‘Modern Writing’, Encyclopaedia of Ireland (Dublin: Allen Figgis 1968), pp.359-61; Irish authors discussed incl. Kavanagh, Clarke, with Heaney, Longley, Donagh MacDonagh, Rutherford Watters [Ó Tuairisc], Iremonger, Montague, Macauley, Holzapfel, Murphy, Harris, Weber, Liddy, O’Grady, Brownlow, and Carew all among ‘others of interest’; singles out Eavan Boland (‘a fine young poet’); Beckett (‘deep structural debt’ to Joyce); Aidan Higgins (‘scrupulous Joycean attention to stylistic precision’); Anthony Cronin (cf. Nighttown); Bernard Share (Joyce-inspired word-play); McGahern (‘rural versions’ of A Portrait); Flann O’Brien (‘vitality of Joyce’s comic genius’); Brendan Behan (‘his boisterous energy’); other novelists are Kiely, Macken, Broderick, Brian Moore, Monk Gibbon, Robert Harbinson, de Vere White, Kate O’Brien, Honor Tracy, Edna O’Brien; also Richard Power and Andrew Ganly; ‘Yet one feels that, in spite of all this, the enduring achievement of Irish prose is in the short story, and extremely difficult and treacherous form ... the Irish genius expresses itself best in brief intensities’; cites Joyce, O’Connor, Lavin, O’Flaherty, O’Faoláin; also James Plunkett, Bryan MacMahon, patrick Boyle, Tom McIntyre, Brian Cleeve and Brian Friel; under theatre, cites Becket, Synge, O’Casey, as models; M. J. Molloy, and John B. Keane as practitioners; and ‘good work’ by Hugh Leonard, Eugene McCabe, and Friel; ‘[t]he Irish theatre is haphazard and lacks a central unifying force, a man ... like Yeats. [asterisk for photo ports., including one of Padraic Colum, not cited in the text. Kennelly is described as ‘the major figure among the young Irish Poets’ [sic], quoting Dictionary of Irish Writers.

Penguin Book of Irish Verse (Harmondsworth: Penguin 1970), Introduction, ‘A poet without a myth is a man confronting famine. Like the body, the imagination gets tired and hungry, myth is a food; a sustaining structure outside the peot that nourishes his inner life and helps him to express it. Most of our younger poets realise this, consciously or unconsciously.’ (p.42; quoted in Terence Brown, Northern Voices, 1975, p.111.)

Writing: ‘[T]he chief thing I’ve learned from my attempts at writing, over the past thirty years, particularly in Cromwell and The Book of Judas, is that we who are floundering through this boggy swamp of time must try to create a poetry in which intense thematic and emotional affinities, illuminating contrasts, fertile and fearless contradictions, as well as startling juxtapositions, will take the place of a poetry that is bullied by dull, predictable chronology and all its ponderous implications. We must, literally, have the time of our lives - and of other lives; contrasts, contradictions and juxtapositions mentioned above become inevitable, and dictate the poem’s technical virtuosity. Violence, delight, humour, and an understanding of my failure to understand so many things and people, are what I’d be chasing in poetry; these would acknowledge the nature and depth of my bewilderment in the face of an increasingly frantic, stupid and money-obsessed world. Against that world I’d place the casual anarchies of ordinary conversation backed by a strong, ancient, mythical set of real presences. I’d let the condemned and glorified dead have their voices so that they’d tell me (and I’d pass it on to you, that you might mull it over) what they really think of damnation and glory; and I’d show glory and damnation at work today in you, in me, in newspapers, telly, radio, significant meetings (‘It seems to me’), chats, yarns, rumours (O my sweet Liffey of gossip!) and every possible product of the scandal-industry that is the true measure of our boredom. / Poetry is the best, perhaps in the end, the only real form of criticism because it puts the self on the line. The main thing is to give this self (O Jesus where’s my pension?) a merciless thumping so that the poem will at least have the validity of enlightened self-laceration. No criticism is valid that isn’t rooted in self-criticism. No poetry is likely to be of living interest to discriminating readers that doesn’t take the micky out of the poet’s own vanity, arrogance and priceless self-deception. We should declare war on ourselves. That’s when the fun starts. That’s when the poem laughs in delight at the violence it does to itself. I want to write a poetry that is capable of containing, among other things, this kind of self-critical laughter. [… &c.] (Contrib. to Krino, ‘The State of Poetry’ [special issue], Gerald Dawe & Jonathan Williams, eds., Winter 1993, pp.28-29; p.28.)

[ top ]

Journey into Joy: Selected Prose, ed. Äke Persson (Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Bloodaxe 1994) - ‘Irish Poetry Since Yeats - II - 1’: ‘Whenever one or two figures seem dominant in a country’s poetry, several others are writing in a different but not equally acclaimed or recognised way. When Yeats was at the height of his powers towards the end of his life, an anthology, Goodbye, Twilight (ed. Leslie Daiken, 1936), was published containing the work of poets who saw themselves as writing a very different kind of poetry from that of Yeats and other distinguished Celtic Twilighters. In 1993, Gabriel Fitzmaurice edited an anthology, Irish Poetry Now: Other Voices which, he holds, contains a kind of poetry different from and interesting as the mainstream of contemporary verse in Ireland. Such oppositions, such alternatives, are a healthy sign; they lessen the likelihood that readers may fall into attitudes of lazy categorisation; and they suggest that the scene is more vigorous, varied and complex than we had hitherto realised. Further, they create the possibility that poets in scrupulous opposition to each other may produce better work. There should be fewer cosy coteries, more fierce and intelligent opposition. That’s the stuff of which genuine friendship between poets is made. / Yeats’s Cuala Press published Patrick Kavanagh’s long poem The Great Hunger in 1942. Kavanagh went on to denounce Yeats as being “protected by ritual” in his poem, “An Insult” (Coll. Poems, 1964, p.185); he also criticised him severely in several essays. This was Kavanagh’s way of distancing himself from Yeats. He went on to explain and express his own vision, a vision which in the end has, ironically, some remarkable similarities to Yeats’s. Kavanagh called it “comedy” (“Signposts”, Coll. Pruse, p.25; also Coll. Poems, p.xiv.); Yeats called it “tragic joy”. (“The Gyres”, Coll. Poems, 1958, p.337.) Kavanagh’s castigating references to Yeats and others helped him to create for himself that space, that freedom from other poets’ work (even as they are deeply aware of it) that most poets need. Poets’ vicious denunciations of the work of others can be forms of self-liberation. (p.55; see longer extract from this passage, infra.)

Journey into Joy: Selected Prose (1994) - ‘Irish Poetry Since Yeats - II 3’: ‘A poet’s relationship with language is one of the deepest there is. The kind of English spoken and written in Irelnd has a twist to it. It can be Janus-faced, crooked, indirect, poisonoulsy comic, inflated, often pretending to a false sophistication, haunted by the Irish language, resenting or cherishing that influence. That English of Dublin is very different from that of Belfast or Cork or Galway. Even within these places there are different Englishes. In poetry, one English is as effective as another, depending on how imaginatively, passionately, skilfully it is used. When these qualities are present it doesn’t matter what town, village, city, region or prison a poet is from: the necessary bridge between the writer and the reader is created. I should point out here, being aware of the approaches of some other poets, that I consider such “bridges” necessary. An unshared poetry might as well be an unwritten poetry. The silence of the unread poem accuses us all.’ (p.67.) Further: ‘I hope this poetry reaches out to more and more people without compromising its seriousness or concealing its limitations. I hope it tackles the troubles that walk the streets, teaches in the schools, preaches in the churches, judges in the courts, festers or prospers in prison (”universities of crime” as one prisoner remarked to me), adores the music and songs of U2 and Sinéad O’Connor, speculates on the Stock Exchange, lives with AIDS, is sexually abused, sexually abuses, becomes anorexic, is unemployed, perhaps hopelessly so, condemns or praises the IRA and the UVF, begs in the streets of Dublin and talks to itself endlessly, lips moving in an eloquent, steady desperation that suggests nobody is listening and nobody ever will listen. [... &c.]’ (p.71.)

Journey into Joy: Selected Prose (1994) - on the Northern Irish poets: ‘A pervasive aspect of the poetry out of the North of Ireland from John Hewitt and Louis MacNeice onwards is a shrewd, reticent humanism. One cannot avoid the word “Protestant” in describing this humanism because it involves the habitual workings of a conscience and/or a consciousness which seem interchangeable.’ Kennelly gives an account of Catholicism ‘with its inbuilt sacramental structure of forgiveness, its absolving paternalism’ and remarks that ‘a system of forgiveness can help to foster a system of criminality’. [127] ‘The humanism I have in mind has little to do with forgiveness; it has everything to do with responsibility. / Humanism is a form of intelligent loneliness. the working of the conscience is, by definition, a solitary activity’. Kennelly defines humanism as ‘anti-Romantic, in the purely literary sense’ and goes on to say: ‘[…] it lays a primary emphasis on the potential of the solitary self, even the isolated self. Therefore it is romantic. Yet, because it refused to use, it is gifted with a special detachment. Therefore it tends to be ironic. Romantic in a special sense, ironic in a special sense. (...; p.127.) ‘[O]nly the Protestant humanist has this special combination in his veins; in the veins of his imagination.’ Kennelly treats of MacNeice’s “Prayer Before Birth” as ‘the prayer of the ironic romantic outsider’ and pays explicit tribute to him as ‘the humanist source of much Ulster poetry’ (p.128). ‘In all his best poems all these elements are held in a calm and dignified balance. It is a quiet voice, not too dramatic. It is a consciously educated voice. It is learned but not pedantic. It is self aware and self mocking. It is perhaps too ironic to be noticeably passionate, and yet there is no doubt of its intensity. It is the kind of voice craves an eloquent linguistic precision and often finds it. It is is a voice of conscience, scrupulously examined, stylishly projected, rhythmically elaborated, a pleasure to hear, mysterious to think about.’ (p.132; see further extracts on Patrick Kavanagh [supra], Flann O’Brien [infra], and Derek Mahon [infra].)

[ top ]

English poets: extract from ‘Patrick Kavanagh’, in Ariel (July 1970), rep. as Chap. XI in Seán Lucy, ed., Irish Poetry in English (Cork & Dublin: Mercier Press 1973): ‘In this respect, the majority of contemporary English poets are in the difficult position of having to be extremely accomplished and sophisticated at a very early stage. Otherwise nobody listens to them. They can’t afford to make mistakes, and unless a poet has both the capacity and the opportunity to make a fool of himself, he will never become anything. The English have lost a sense of the value of naïveté and most of their poets have substituted a passion for fatal perfection which, around the age of thirty, makes them invulnerable to criticism and usually incapable of development. This perfectionism involves a very prosaic conception of precision and concentration. It’s the sort of disease against which Blake and Keats fought. (At the moment, sad traces of it can be detected in Irish writing.) Patrick Kavanagh never suffered from abortive ideas of sophistication. Like all the true visionaries, his aesthetic, scattered carelessly in fragments here and there, is distinguished by its sanity and sheer good sense. It is also blissfully free of all pretentiousness and obscurity. The clarity of all his statements on poetry is a mark of his confidence and clearsightedness.’ (Lucy, op. cit., 1973, pp.160-61.) Vide Kavanagh’s remarks about the contempoary ‘materialist’ English poets in Author’s Note, Collected Poems, 1964, infra. [Note: The above passage was deleted from the version of the article rep. in Åke Persson, ed., Journey into Joy: Selected Prose (Newcastle: Bloodaxe 1994), pp.109-26.]

“Sugto”: ‘Sorth and Nouth, territories occupied / in his wordscape by / Protholics and Catestants / as they live and die / in the shat-on beauty of their island. / Noyalists and Lashionalists picnic together / in all kinds of weather, / chewing tarpition [partition] sandwiches with sugto [gusto] / […]’ (Poetry My Arse, Newcastle upon Tyne: Bloodaxe Books 1995, p.75; quoted in a Anna Asián & James McCullough, ‘A Student’s Guide to Hiberno-English’, 1998 [supra].)

All work ...: ‘Exams ... they’re the basis by which generations of people are judged on their intellectual ability. You ask a question, and you get an answer. But, of course, that’s a very oversimplified way of approaching knowledge, isn’t it? Why not ask a question and get another question? If I had to define what is the nature of education I would say it’s asking questions. All your life don’t ever settle for answers. And you’ve got to keep on asking questions, and secondly, you’ve got to keep on having fun with life.’ (In interview with Lynn McBrien, CCN Student News, 2. Jan. 2001; copy & link.)

See extract from Kennelly’s “Questions & Answers” session with W. H. Auden |

[ top ]

References

Peter Fallon & Seán Golden, ed, Soft Day, a Miscellany of Contemporary Irish Writing (Dublin: Wolfhound Press; Notree Dame UP 1980), selects ‘The Thatcher’; ‘The Swimmer; ‘Bread’; ‘Proof’.

Patrick Crotty, ed., Modern Irish Poetry: An Anthology (Belfast: Blackstaff Press 1995), selects from Cromwell: “Three Tides” [194], “Vintage“ [195].

[ top ]

Notes

Dark fathers?: Kennelly ’s poem “My Dark Fathers” possible owes something to Patrick Kavanagh ’s lines in “Dark Ireland”: ‘We are a dark people, / Our eyes are ever turned / Inwards / Watching the liar who twists / The hill-paths awry. / O false fondler with what / Was mde lovely / In a garden!’ (Quoted in Sister Una Agnew, The Mystical Imagination of Patrick Kavanagh, Columba Press 1998, pp.28.

‘River of Words’, RTE Wed. 26 June 1994, ‘Brendan Kennelly’ [ Previous two numbers dealt with George Fitzmaurice and J. B. Keane].

Cromwell: Seamus Heaney has written of ‘a male cult whose founding fathers were Cromwell, William of Orange, and Edward Carson’, and whose godhead is figuratively Roman, “incarnate in a rex or caesar resident in a place in London”’ (Preoccupations: Selected Prose, 1980, p.57; quoted in Elizabeth Butler Cullingford, ‘British Romans and Irish Carthaginians: Anticolonial Metaphor in Heaney, Friel and McGuinness, PMLA, March 1996, pp.222-36, p.229.)

Irish epic: Brendan Kennelly called Michael Farrell’s novel Thy Tears Might Cease (1963) the first Irish novel of epic stature since Ulysses in a (Hermathena review (XCIX, Autumn 1964) [See further under Farrell, infra].

Summer School: The Brendan Kennelly Summer School was inaugurated at Ballylongford on 9-12 Aug. 2001 with guests incl. Desmond Fitzgerald (Knight of Glin), Theo Dorgan, Miriam Purtill, and John McDonagh [email].

Toyota-town: Bob Quinn, Maverick: A Dissident View of Broadcasting (2001), writes: ‘Even allowing for the possible geriatrification of my taste buds, I could not see how on every conceivable occasion the offer of, say, a free t-shirt made of recycled Kellogg’s Corn Flakes to everyone in the [Late Late Show] audience was contributing more than a sick joke to the gaiety of the nation. Nor could I see how giving a free, show-long promotion to a Toyota car so that somebody could drive it away buckshee and total it on a stone wall in Ballyjamesduff made good economic sense, even if the vehicle was endorsed by a poet [i.e., Brendan Kennelly].’ (Aubrey Dillon-Malone, review, Books Ireland, Dec. 2001, p.328.)

Judas (the play): Stage version of The Book of Judas preparted for Theatre Unlimited by Maciek Resczcynski; produced at Kilkenny Arts Fest., with Adrian Dunbar as Jesus, and Phelim Drew as Judas. Resczcynski previously dramatised Cromwell for Kavanagh’s Yearly gathering at Carrickmacross, and later at Trinity College, Dublin, GMB, transferring to Damer Hall and onwards to Bush Th., London; Resczcynski worked with Contemporary Theatre Co. of Wroclaw, which brought Birthrate to the Dublin Th. Fest. in 1982 and returned the year after with its production of Finnegans Wake; Resczcynski m. Dáire Brehan, prev. of DU Players; set up Theatre Unlimited in Kilkenny; has played Tom McIntyre such as Dance for Your Daddy; now lives in England as computer-whizz for BBC; Judas perf. Kilkenny Arts Fest., 12-20 Aug. 2000 (Report in Irish Times, 5 Aug. 2000.)

The dancing man: Kennelly writes of his father, a man who liked to begin each day with a little dance, whom he remembers thus before mind and body were broken. (See video of poem readings on Bloodaxe website - online; accessed 24.02.2011.)

Heaney’s Sweeney: Kennelly reviewed Heaney’s Sweeney Astray: A Version from the Irish, in New York Times Book Review, 1984 - calling it ‘a balanced statement about a tragically unbalanced mind. One feels that this balance, urbanely sustained, is the product of a long, imaginative bond between Mr. Heaney and Sweeney.’

Michael Hartnett dedicated “Farewell of English” (1975) to Kennelly (Collected Poems, Gallery 2003, pp.141-47; also given in Soft Day: A Miscellany of Contemporary Irish Writing, ed. Peter Fallon and Sean Golden (Wolfhound Press 1980, p.142-45.)

Declan Kiberd has a chapter entitled ‘Protholics and Cathestants’ in Inventing Ireland (1995), p.418ff. - reflecting the coinage arrived at by Kennelly. Kiberd was an undergraduate student of Kennelly’s at TCD.

The Brisset Affair: Articles in the Irish Independent and Trinity News (TCD) in 2013 reflect the facts that Brendan Kennelly was upset by disclosures about the sexual abuse of his daughter Doodle by an older man while she was a teenager living the rock ’n roll lifestyle, and that she herself was greatly offended by the revelations which came as a shock to her own daughters. Subsequently a lecture on Kennelly by Sandrine Brisset scheule to be given on 10th Oct. 2013 in the Long Room of TCD Library - initually under the title of “Bardic Poetry in Modern Ireland” - was cancelled at the instance of the poet. Brisset, formerly a lecturer in Law and latterly in English at St. Patrick’s College, Drumcondra, began her work on Kennelly while still at Rennes University and claims to have spend ten years at it, during which she was a close and trusted friend of Kennelly. (See Barry Egan, ‘Kennelly furious over biography’, in The Irish Independent, 23 June 2016 - available online; Trinity News, 18 Oct. 2013 - available online; both accessed 19.12.2016.)

Note: Kirsten “Doodle” Kennelly (1970-2021) divided her time on childhood between her mother’s home in Amherst, Mass., and her father’s home in Ireland; she was a one-time columnist for the Irish Independent, where she wrote about her struggles with mental health and other issues; a notice of her death in Blackrock, Co. Dublin, appeared in the edition of that paper for 20 April 2021, and referred to three daughters, Meg, Hannah and Grace with her husband Peter. (See Irish Independent, 20 April 2021 - online.) An obituary by Barbara McCarthy appeared in the Irish Independent on 25 April 2021 - quoting Kennelly’s line, ‘The best way to serve the age is to betray it’ (Book of Judas) and celebrating his daughter as a harbinger who opened the conversation about mental health. In internet photos the Judas line can be seen in the form of a tattoo across her shoulders. She was a devotee of heavy metal music and Kurt Cobain and was working on an unfinished novel called Life Through a Spoon when she died suddenly in April 2021. [online; accessed 19.10.2021].

[ top ]