Lady Morgan: Commentary & Quotations

| Commentary | Quotations |

| William Hazlitt hears good things of Lady Morgan: ‘[...] I am told that some of Lady Morgan’s are very good, and have been recommended to look into Anastasius but I have not yet ventured upon that task.’ (“On Reading Old Books”, in the London Magazine, Feb. 1821; rep. in English Romantic Writers, ed. David Perkins, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Inc. 1967, pp.665-66.) |

R. L. Edgeworth (letter to Sydney Owenson): ‘As a sincere and warm friend of Ireland, I return you my thanks for the just character which you have given to the [73] lower Irish, and for the sound and judicious observations which you have attributed to the priest. The notices of Irish history are ingeniously introduced and are related in such a manner as to induce belief among infidels ... Maria, who reads (it is said) as well as writes has entertained us with several passages from The Wild Irish Girl which I thought superior to any part of the book I had read. Upon looking over her shoulder I found she had omitted some superfluous epithetcs. Dare she had done this if you had been by? I think she would have dared, because your good taste and good sense would have been instantly her defender.’ (Quoted in Mary Campbell, Lady Morgan: The Life and Times of Sydney Owenson, London: Pandora 1988, pp.73-74.)

John Wilson Croker [as “M.T.”], in Freeman’s Journal (Dec. 1806); ‘I accuse Miss Owenson of having written bad novels and worse poetry – volumes without number, and verses without end, nor does my accusation rest upon her want of literary excellence. I accuse her of attempt[ing] to vitiate mankind - of attempting to undermine morality by sophistry and that, the insidious mask of virtue, sensibility and truth.’ Croker further charged St Clair, or the heiress of Desmond (1803) with ‘unbridled licence ... a continued vein of immorality’ (ibid.) [See further in Patrick Rafroidi, Irish Literature in English, The Romantic Period, 1789-1850, Vol 1 (Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1980) - under Croker, supra.]

Freeman’s Journal (in 1807): ‘It may justly be said that this young lady is one of the greatest ornaments our country could ever boast of: she moves in the very highest circles, courted and admired as well for her unrivalled talents as her elegant and unaffected manners; she is realising we hear a noble independence by the exertion of her own highly cultivated and expanded mind.’ (Quoted in Mary Campbell, op. cit., 1988, p.82.) Note that the Journal previously printed J. W. Croker’s attacks on The Wild Irish Girl in 1806, and for some time after; see Croker, supra.)

Jane Austen: ‘We have got Ida of Athens by Miss Owenson, [who] must be very clever, because it was written, as the authoress says, in three months. We have only read the Preface yet, but her Irish Girl does not make me expect much. If the warmth of her language could affect the body, it might be worth reading in this weather [i.e., Dec.]’ (Quoted in Mary Campbell, op. cit., 1988, pp.95-96.)

George Pepper [q.v.], A History of Ireland [...] (Boston: Devereaux & Donahoe 1835) [quotes with approbation Livy on memorial records (“Quæ ante conditam condendamve ... &c.)]: ‘Lady Morgan, to show the reader the remains of our ancient renown and glory, mouldering in the catacombs of the Irish annals. There is not now in existence, and we say it unhesitatingly, any person who could write a better history of that country, of which she is the pride and the ornament, than her Ladyship. The profundity of her research — the flowery luxuriance of her style — the fervour of her patriotism — the philosophy of her investigations — and, above all, the intimate acquaintance which she [vi] has with the language in which Ossian sung, and Brian Boroihme bade defiance to his foes, would enable her to reflect the concentrated rays of these brilliant combinations, on a History of Ireland, that would wither the laurel wreaths, with which the historic Muse entwined the brows of a Gibbon, a Hume, and a Henry.’ (Introduction, pp.6-7; available at Internet Archive - online.)

Maurice Egan, ‘Irish Novels’, in Justin McCarthy, ed., Irish Literature (Washington: Catholic Univ. of America 1904), Vol. VI, pp.vii-xvii: ‘The Wild Irish Girl and The O’Briens and the O’Flahertys deserve respect; they opened vistas of the past to people who seemed, in their despair, to have neither past nor future. Say what we will, - to give a man a pedigree is to give him self-respect. Lady Morgan’s taste is not always correct; she is often as untrammelled in her sarcastic epithet as the first Lady Bulwer-Lytton; but she loved a nation that then had few to love it.’ (p.viii; previously printed as ‘On Irish Novels’ in Catholic University Bulletin [Washington, D.C.], Vol. 10, No. 3, July 1904, pp.329-41.)

Vivian Mercier, The Irish Comic Tradition [1962] (OUP 1994 Edn.): ‘[Lady Morgan’s] scenery was wild and unfamiliar and many of her people, besides being very poor and sometimes romantically lawless, still spoke a foreign language. Best of all, perhaps, from the standpoint of the Protestant British reader, Ireland and Italy had in common the picturesque, sinister, superstitious, and yet prestigiously ancient Roman Catholic Church.’ (p.41; quoted in Ann Cahill, ‘Irish Folktales and Supernatural Literature: Patrick Kennedy and Sheridan Le Fanu’, in That Other World: The Supernatural and the Fantastic in Irish Literature, ed. Bruce Stewart [Transactions of Princess Grace Irish Library Conference; Monaco, Whitsun 1998], Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1998.)

Patrick Sheeran, “The Novels of Liam O’Flaherty: A Study in Romantic Realism” [Ph.D. Diss.] (UCG 1972): Lady Morgan’s works The Wild Irish Girl, O’Donnel, The O’Briens and the O’Flahertys are more purely romantic in form than anything Maria Edgeworth wrote. It is plain, from stray remarks in her Memoirs and letters, that she consciously wrote within the romance form. The strange amalgam of diverse elements which constitute these romances is best brought out by a letter of advice to her from her mentor and friend Joseph Cooper Walker, author of a History of Irish Music. Lady Morgan (then plain Miss Sydney Owenson) is in the West of Ireland struggling with The Wild Irish Girl: “You are now in a part of the island where many of the Finian tales are familiarly known.” [&c.’; quoting Lady Morgan’s Memoirs: Autobiography, Diaries and Correspondence, ed. W. Hepworth Dixon, London 1862, as given under Walker, q,v, infra.] (Cont.)

Patrick Sheeran (“The Novels of Liam O’Flaherty: A Study in Romantic Realism”, 1972) - cont.: ‘J. C. Walker, in concluding his letter sends his respects to Miss Owenson’s father from whom his correspondent derived a further influence - her penchant for melodrama and the theatrical construction of her novels. He was the manager of the National Theatre and later, deputy-manager of the Theatre Royal. In bad times he took the lead in numerous melodramas and farces where it was his custom to insert patriotic airs for the honour of the Nation. The practice finds a counterpart in his daughter’s works where she strikes out again and again at the political and religious condition of the Irish people. The “element of romance” as her friend and editor, W. Hepworth Dixon, put it, “perhaps enables the reader to go through political discussions and statistical details of the then existing state of things in Ireland, which otherwise would not have been tolerated [...]”’ (Ibid., Vol. II, p.77; Sheeran, p.175; for full text version, see RICORSO Library, “Irish Critical Classics”, via index, or direct.).)

Patrick Rafroidi, Irish Literature in English, The Romantic Period, 1789-1850 (Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1980), Vol. 1, remarks on Lady Morgan’s freeing of France from the literary ostracism imposed by Burke, and her endorsement of Rousseauesque Naturalism. ‘Her St. Clair was modelled on Werther, and shows traces of Nouvelle Heloïse; the feminism of Ida of Athens owes much to Mme de Stael; Madame Cottin’s Mathilde is recognisable in The Missionary, and also Atala by Chateaubriand. Her France (1817) was a forerunner of British essays devoted to France, pioneering romantic sociology and showing the nation emerging from the French Revolution as a worthy people. It was subjected to abuse by French and English conservatives, including the French translator, who added vitriolic notes.’ Bibl., Marcel Ian Moraud, Une Irelandaise liberale en France sous la Restauration, Lady Morgan (Paris: Didier 1954). A second volume of impressions, France in 1829-30, followed from a journey to forget disappointments in Ireland.’ [43-45; cont.].

Patrick Rafroidi (Irish Literature in English, 1980), Vol. 1 - cont.: quotes a lengthy judgement on her poetry from the French critic already cited [viz., Moraud], remarking on ‘the lack of vitality and the poverty of [...] inspiration’ in the imitative verse of the young Sydney Owenson, excepting only poems dedicated to her father (“The Picture”) and her mother (“Retrospection”).[c.56] [For her treatment by John Wilson Croker, q.v., see under Croker, supra]. Further, quotes Lady Morgan, a farewell to Ireland, in her diary [as in “Quotations”, infra; here 108]. Rafroidi quotes accounts of the Giant’s Causeway, respectively from Maria Edgeworth and from Lady Morgan, the former beginning, ‘In the bold promontory of Bengore, you behold, as you look up from the sea, a gigantic colonnade of basalts, supporting a black mass of irregular rock [...] &c.’. The second begins, ‘The great and stupendous features which characterise the coast of Antrim, now gradually developed themselves, in all their rudest grandeur. Promontories, bold and grotesque; bays deeply insulating the mountainous shores; rocks fantastically group [...] / The sun was setting with great richness over the Heights of Sliabh-Barragh [...; 110]. See also remarks on St. Kevin’s Bed [see infra].

W. B. Stanford, Ireland and the Classical Tradition (IAP 1976; 1984), Lady Morgan set Woman, or Ida of Athens (1809) in modern Greece; she resisted the temptation to learn Greek and Latin ‘lest I should not be very woman’ (see L. Stevenson, The Wild Irish Girl, London 1936, 108ff, 116ff.) Further, Lady Morgan’s Woman and Her Master (1840) contains a chapter on the status of women in ancient Greece and Italy hardly more than partisan journalism. Dublin University Magazine - unfairly, thinks Stanford - described it as ‘a work without one claim to notice except the antiquity of its author.’ [12] Further remarks that Woman, or Ida of Athens (1809) painted a compassionate picture of the plight of the Greeks under the Turkish rule and strongly asserted their right to freedom, implying that their subjection to Turkey was comparable with that of Ireland to Britain. [223]

[ top ]

Tom Dunne, ‘Fiction as “the best history of nations”, ‘Lady Morgan’s Irish Novels’ in Tom Dunne, ed., The Writer as Witness, Literature as Historical Evidence (Cork 1987), pp.133-59, argues that a major aim of her project was to demonstrate that fears of a Catholic challenge to the property settlements of the plantation period were ungrounded. [as summarised in Dunne, ‘Edgeworthstown in Fact and Fiction, 1760-1840’, in Longford: Essays in County History, ed Raymond Gilespie and Gerard Moran, Lilliput 1991, p.101.]

Mary Campbell, Lady Morgan: The Life and Times of Sydney Owenson (London: Pandora 1988): ‘It is given to few lady novelists to be under the constant surveillance of the security police, or the politics of the nation to be argued out in the rhetoric of her romantic fiction. But for [ix] a period in the first half of the nineteenth century, between the Act of Union which brought to an end the rule in Ireland of the Ascendancy, and the Famine, which brought to an end the old Gaelic peasant world, the novels of Sydney Morgan had a potency that affected such issues as Catholic emancipation, the Repeal of the Union, and the whole question of English rule in Ireland and made her the object of the attentions of the secret police, both in England and in Ireland, and abroad. This might seem very heavy treatment for someone who claimed to make up “tissues of woven air, in which I then clothe my heroines”. But out of these tissues she created the image of herself, so powerful that in the public’s mind she took on the persona of her most original heroine – Glorvina, the Wild Irish Girl.’ (pp.ix-x.) [...; cont.]

Mary Campbell (Lady Morgan, 1988) - cont.: ‘If she was well rewarded she was also widely reviled. All through her professional life she was attacked by powerful and influential critics, not so much for her literary lapses as for her Whiggish and Jacobin opinions. And all through her life she fought them valiantly, and they could dent neither her spirit nor her popularity. But now that she is dead, it is a very different story. Eminent literary historians since her death have either ignored her or dismissed her as a footnote in literature. And today she has more or less been written off. One Irish writer has recently - without giving evidence to support his claim - called her “a trashy novelist”. These generalisations are as unfair now as was the criticism she suffered when she was alive - for having too much significance! For the sake of literary history it is necessary to understand why she was considered so important in her own time and, in spite of her relegation to the ranks of writers now deemed obsolete, how much she can still contribute to an understanding of the social, political and religious problems that still bedevil Ireland today. Her “national” tales analysed the conflicts in Irish society then which led eventually to the troubles of all the ensuing years, and her advocacy of justice and tolerance might still be heeded with some better results.’ (p.x.) [ …; cont.]

Mary Campbell (Lady Morgan, 1988) - cont.: ‘When Sydney Morgan started to write, this was the stereotype she had to break. She herself was the victi m of racist end sexist prejudice on a horrendous scale, which she fought vigorously and successfully. In one of her fighting prefaces she reminded her readers that she wrote in an age “when to be a woman was to be without defence, and to be a patriot was to be a criminal”. She was proud to be both a woman and a patriot, and endeavoured to raise the status of her country and er sex, even though as her friend and observer Mrs S. C. Hall remarked, “Envy, malice and uncharitableness, these are the fruits of a successful career for a woman.” […] Lady Morgan was the first Irish writer of the nineteenth century to express the passion and commitment of those members of the Anglo-Irish who espoused the nationalist cause. Before her, writing in Ireland had been a colonial literature, written for English publishers and an English readership. She found themes that were deeply relevant to the Irish – themes of religion and racial heritage, and family loyalties in a broken society – and at the same time made these matters palatable and comprehensible to an English public [xi; …. Her novels – if one is looking – contain a key to the “Irish problem”. To ignore her is to reject the potency of great literature.’ (pp.xi-xii.) Also quotes Thomas Davis: ‘Nationality is the summary name for many things. It seeks a literature made by Irishmen and coloured by our scenery, manners and characters. It desires to see Art applied to express Irish thoughts and beliefs. It would make our music sound in every parish at twilight […] and our poetry and history at every hearth.’ [No source; here p.xii.]

R. F. Foster comments on the scene in Wild Irish Girl (1806) in which the innocent hero inherits an Irish house with a locked library containing books on Irish history, making comparison with the library that triggered Standish O’Grady’s interest in Ireland. (‘The Magic of Its Lovely Dawn, Reading Irish history as Story’ [Carroll Inaugural Lecture]; version printed in Times Literary Supplement, 16 Dec. 1994).

Ina Ferris, ‘Narrating Cultural Encounter: Lady Morgan and the Irish National Tale’, in Nineteenth Century Fiction, Vol. 51 No. 3 (Dec. 1996), pp.287-303, writes: ‘As a worldly and impure genres that sets out to do something with words, the national tale makes central to its whole project the often obscured, performative notion of representation itself [...] so closely identified in our critical thinking with mimesis … that its performative sense has been largely overlooked.’ (ftn. ref. to Murray Krieger, ed., The Aims of Representation Subject / Text / History, Columbia UP 1987.) Further: ‘The presentation of something to someone so as to create a certain effect’ [289]; ‘national defence [...] fictitious narrative, founded on national grievances, and borne out by historic fact.’ (Pref. Address, Wild Irish Girl, rev. edn., 1846, p.xxvi.) [290]; ‘Born and dwelling in Ireland, amidst my countrymen and their sufferings, I saw and described, I felt and I pleaded; and if a political bias was ultimately taken, it originated in the natural condition of things.’ (Preface to O’Donnel, rev. edn. (Colburn 1835, p.ix) [290]. (Cont.)

Ina Ferris, ‘Narrating Cultural Encounter: Lady Morgan and the Irish National Tale’ (1996) - cont.: ‘The Wild Irish Girl not only offers a history of Ireland countering the official London-based narrative, but it also sets up an elaborate subtext of footnotes in which a personal, authorial voice criticises, revises, commends, and otherwise enganges a plethora of texts on Ireland written from different points of view (and sometimes in different languages).’ Further: ‘[W]hat remains constant in the effect of encounter with this heroine: she disconcerts and confounds the aasumptions and identities of the strangers who come across her in the hinterland. / The key to the Irish national tale inaugurated by Morgan is thus her rewriting of the romance trope of transformative encounter. Recasting [the] encounter as a breaching of the universal of metropolitan reason by the specificities of body and voice, she allows for an unsettling of imperial identity in colonial space through the attainment of a problematic proximity.’ (p.299; cont.)

Ina Ferris, ‘Narrating Cultural Encounter: Lady Morgan and the Irish National Tale’ (1996) - cont.: Ferris argues that in Edgeworth’s Ennui ‘it is the voice of a native Irishwoman that effects the initial dispacement of the young English hero [Glenthorn]: “I did not understand one word she uttered, as she spoke in her native language, but her lamentations went to my heart, for they came from hers.”’ (Marilyn Butler, ed., Ennui, Penguin 1992, p.156; here 300); ‘Through its narratives of encounter the Irish national tale sought to place certain forms of metropolitian reason under pressure and loosen their configuration. This does not mean, it should be stressed, that the genre repudiates the rational. [302]; calls Morgan and Edgeworth the ‘main practitioners’, but instances Maturin, The Milesian Chief; quotes Lyotard, ‘The only way that networks of uncertain and ephemeral stories can gnaw away at the great institutional narrative apparatuses is by increasing the number of skirmishes that take place on the sidelines.’ [‘Lessons in Paganism’, in Andrew Benjamin, ed., The Lyotard, Oxford Blackwell 1989, p.132; here 303].

Bibl., Terry Eagleton, Heathcliff and the Irish Famine; also Seamus Deane, ‘Irish National Character 1790-1900’, in The Writer as Witness: Literature as Historical Evidence, ed. Tom Dunne (Cork UP 1987), cp.103; Claire Connolly, ‘Gender, Nation and Ireland: The Early Novels of Maria Edgeworth and Lady Morgan’ (Diss. Univ. of Wales 1995); Deirdre Lynch, ‘Nationalising Women and Domesticating Fiction: Edmund Burke and the Genre of Englishness’, in Wordsworth Circle, 25 [1994], pp.45-49; Robert J. C. Young, Colonial Desire: Hybridity in Theory, Culture and Race (NY: Routledge 1995).

Joep Leerssen, Remembrance and Imagination: Patterns in the Historical and Literary Representation of Ireland in the Nineteenth Century (Cork UP/Field Day 1996) - quotes a passage from The Wild Irish Girl (1808) in which the narrator Horatio recounts an Irish lesson conducted by the Glorvina’s father, the Prince of Inismore, in which he calls on Glorvina to recited conjugate the Irish [Gaelic verb “to love”] - which they do, with suitable romantic sparks flying between them. The passage - which is not identified in the ensuing footnote reference - contains an allusion to Vallancy as the author of an Irish grammar: ‘The attenton of the simple Prince was rivetted on Vallancy’s grammar: he grew peevish at what he called our stupidity, and said we knew nothing of the verb to love, while in fact we were running through all its moods and tenses with our eyes and looks.’ (Leerssen, p.59.) In an extensive footnote, Leerssen points out that, while amo, amas, amat are familiar from the schoolroom conjugation of the Latin verb (amare), the Irish expression is not a simple verb but rather a prepositional phrase: ta gra agam (duit) - there is love with [sic] me (for you). He adds: ‘There is nothing of the kind in “Vallancey’s grammar’, of course (presumably Charles Vallancey’s Grammar of the Iberno-Celtic or Irish Language of 1782).” Leerssen goes on to compare the scene in Brian Friel’s Translations where a similar exercise in Graeco-Latin-Irish translation is undertaken in conversational form and remarks: ‘Thus the representation, through English, of verbal activity in Gaelic, though intended as a gesture of rendering the other language present, tends to present a generice “other speech”, modelled on English. The representation mimics, not the Irish language, it its being the vehicle of difference; and we slide back into the exoticist projections and schemata. More importantly, the turbulent interference between wooing and linguistic parroting in Morgan’s cited passage foreshadows directly the bilingual (or rather sequilingual) place-naming love scenes in Translations.’ [See also quotation from Terry Eagleton’s Heathcliff and the Great Hunger - as supra.)

Further: ‘In my view, the antiquarians constituted an interface between the Anglo-Irish, Protestant elite and Ireland’s Gaelic sub-culture, and they did much to formulate a Gaelic iconography of Ireland’s national identity - thus indirectly preparing the slock of images on which cultural nationalism like that of Davis and Pearse could draw. That tradition includes names like Charles Vallancey, Joseph Cooper Walker, Sylvester O’Halloran or Thomas Campbell, whose work has deeply influenced our image of ancient Ireland, though their names may no longer be common currency. But those names are all there, in the footnotes of Lady Morgan - their last discernible presence in the realm of literature, perhaps, before they disappeared from sight under new sediments and in a new stratification of discursive practice. [/...] The names of Vallancey, O’Halloran, Walker and the others were to lose their currency in these post-Union decades. In the realms of archeology and philology these men were eclipsed by more scientific successors, and were dismissed for being too fanciful, while from the realm of literature proper they were dismissed for being too referential, too academic. Yet with Morgan they are still there, half-hidden at the bottom of the page, in the small print. If one wishes to contend that the antiquarians of the late eighteenth century more or less fixed the iconography of a Gaelic Ireland, then the mediation of Morgan - a mediation across the gradually widening divide in the field of belles lettres, between referential discourse of the Enlightenment and the fictional “literature as art” of the nineteenth century - is of cardinal importance. The Wild Irish Girl marks the introduction, the translation of the antiquarian iconography into Anglo-Irish literature.’ (Leerssen, op. cit., 1996, p.61.)

[See Leerssen’s further remarks about the ‘Gaelocentric tradition of cultural nationalism’ under Leerssen > Quotations, as supra - remarks which include the follow summary of the utility amid the nineteenth-century Irish culture transactions of the ‘marriage’ of Horatio and Glorvina:]

‘Here is another facet of that mind-set which I term auto-exoticist. Not only daes it involve the reflex to “see ourselves as others see us” [Burns], or in the “cracked lookingglass of a servant” [Joyce], or in an amused fascination with one’s own quaint- ress; it is also an exoticist preoccupation with the curious, unknown nature of island’s other, Gaelic culture, while at the same time enshrining that culture as a central part of one’s national identity. Irish cultural nationalism as a form of internalized exoticism takes its initial shape in a romantic atmosphere, as expressed most powerfully for the first time in The wild Irish girl. Perhaps Horatio finds a new meaning in life, a healing for his ennui, his spleen, his prejudice, through the tender ministrations of Glorvina and in the interesting world of Irish life. But he is not only the taker in this bargain, for he has something to offer too. He is an audience. He is someone, at last, to whom the incestuous preoccupation with the past and with national traditions can be divulged; he is someone who does not yet know, someone for whom the Irish identity is still unfamiliar. It is he who makes Ireland interesting, who makes Ireland exotic, to whom everything can be told and explained. Here at last is someone to whom the Gaelic Irish tradition can show how very quaint it is; and he marries into that tradition. The onlooker whose standards define quaintness becomes part of the family, and the value of exoticism can be interiorized.’ (Leerssen, op. cit., 1996, p.67.)

[For longer extracts from the concluding passage in Leerssen’s chapter entitled “The Burden of the Past”, see his remarks on ‘Gaelocentric tradition of cultural nationalism’ - under Leerssen > Quotations - as supra.]

[ top ]

Katie Trumpener, Bardic Nationalism: The Romantic Novel and the British Empire (Princeton UP 1997), ‘[... W]hen Irish and Scottish novelists set out to bring the claims of nationalism into the novel, they usually turn to an antiquarian and bardic version of nationalism that is already thirty or forty years old. There are several possible explanations for this fact. / 1. This revival is internally coherent. Because the literature of nationalism is concerned, again and again, with the renewal of past glories and traditions, it is only appropriate that it commemorate and celebrate its own history. This nationalist novels of the early nineteenth century need to be understood, therefore, as a kind of explicit homage to an ealier literary nationalism. Sydney Owenson’s O’Donnel: A National Tale (1814) features a heroine name Charlotte O’Halloran (in tribute to late-eighteenth-century antiquaries Sylvester O’Halloran and Charlotte Brooke), and Alicia leFanu’s Tales of a Tourist (1823) an antiquary named O’Carolan (honoring both O’Halloran and the eighteenth-century harper, composer and poet Carolan.) Indeed, we are able to recognise the late eighteenth century as the formative movement for modern cultural nationalism in part because the subsequent novelistic tradtion continually enshrines it as such. Novels such as James M’Henry’s O’Halloran, or The Insurgent Chief: An Irish Historical Tale of 1798 (1824) track the movement from an antiquarian and bardic nationalism to revolutionary nationalism with great explicitness: if M’Henry’s title characte rat first seems only to echo the political rhetoric of his eighteenth-century namesake, he will eventually lead to the 1798 rebellion.’ (pp.13-14.)

Trumpener, Bardic Nationalism: The Romantic Novel and the British Empire (Princeton UP 1997) - further remarks: ‘Recent Irish and Scottish novels form Sydney Owenson’s Wild Irish Girl (1806) to Charles Maturin’s Milesian Chief (1813) and Walter Scott’s [18] Waverley (1814) have imbued the image of the harp-playing heroines with a great deal of picturesque and romantic charm, signifying a poetic soul and a reverence for national traditions. / Yet Mary’s complaints about her trouble in finding a farmer to transport her harp [in Mansfield Park] reveal the superficiality of her engagement with everything the instrument represents [...; /] As a bardic instrument, the cherished vehicle of Irish, Welsh, and Scottish nationalism, and then as the emblem of a nationalist republicanism, the harp stands for an art that honors the organic relationship of a people, their land, and their culture. In Mary Crawford’s hands, it is deployed for purely picturesque effect. [...]’ (pp.18-19.)

Katie Trumpener suggests that the national tale - as a type of literature - usually reveals that ‘[a] landscape assumed to be barren and backward reverberates with the sound of an ancient culture.’ (Bardic Nationalism: The Romantic Novel and the British Empire, Princeton UP 1997, p.141; quoted in unrecorded review.)

Gerry Smyth, The Novel and the Nation: Studies in New Irish Fiction (London: Pluto 1997), includes commentary: ‘The Wild Irish Girl (1806) [involves a discourse] heavily dependent upon English notions of what life in the Celtic margins should be - romantic, sentimental, wild [44] and natural, capable of healing the rift between Nature and an overly refined European civilisation in danger of complete enervation. [.../...] It could be said that the Ireland of Lady Morgan functions as a sort of English unconscious - a site where the fears and desires reperssed under the pressure of the real world of capitalism and imperialist politics surface. This is a typical strategy of containment, a means of securing one’s own identity by the invocation of all that is different yet uncannily familiar and attractive at the same time. History is reduced to personality and “Ireland” becomes the quaint, exotic, romantic object of the colonial gaze./ What The Wild Irish Girl reveals, in fact, is the radical instability of an Irish identity founded on conflicting notions of equality and difference, and the formal problems ensuing from such a wide discrepancy between narrative and audience. Instead of Bakhtinian carnival the Irish novel can all too readily degenerate into a kind of fictional zoo - a space where sophisticated English readers may visit to marvel at the sheer otherness of Ireland before returning once again to the security of metropolitan normality.’ (p.45.)

| Kevin Whelan, “The Wild Irish Girl” [section], in ‘Reading the Ruins: The Presence of Absence in the Irish Landscape’, in Surveying Ireland’s Past: Multidisciplinary Essays in Honour of Anngret Simms, ed. Howard B. Clarke, et al. (Dublin: Geography Publications 2004), c.p.300ff [copy here attached]. |

|

|

|

| Whelan, op. cit.; see full-text - as attached. |

[ Note: Kevin Whelan has written a foreword to The Wild Irish Girl [1806], ed. Claire Connolly & Stephen Copley (London: Pickering & Chatto 1997). ]

[ top ]

Claire Connolly: ‘Writing the Union’, in Acts of Union: The Causes, Contexts and Consequences of the Act of Union, ed. Dáire Keogh & Kevin Whelan (Dublin: Four Courts Press 2001): ‘Irish national romances such as Sydney Owenson’s The Wild Irish Girl (1806) or Maria Edgeworth’s The Absentee (1812) do not then simply reproduce the imagery of union; rather they thicken and intensify that language, creating in the process new and affective political possibilities.’ (p.181.)

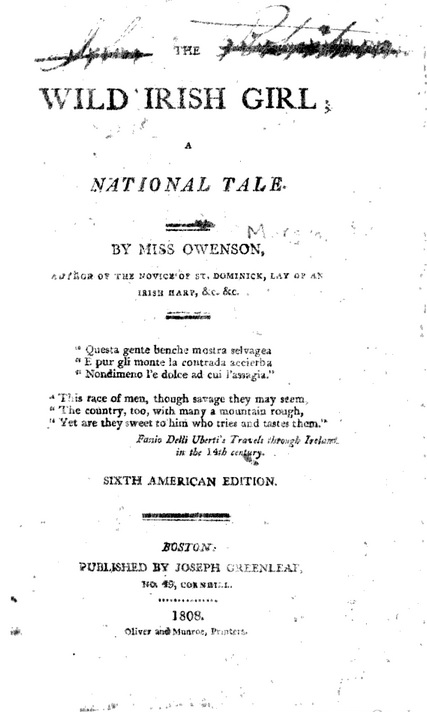

Claire Connolly, ‘Irish Romanticism, 1800-1839’, in Cambridge History of Irish Literature (Cambridge UP 2006), Vol. I [Chap. 10]: ‘[...] The decade after the Union saw the emergence of the national tale, product of the precocious literary talent of Sydney Owenson (later Lady Morgan) (c..1783-1859). Her greatest success was The Wild Irish Girl: A National Tale (1806), the text now credited with the first use of this innovative brand or badge of generic identity. Owenson had published two earlier novels, St Clair; or the Heiress of Desmond (1803) and The Novice of St Dominick (1806). The former was first published in Dublin, and is worthy of note as one of the few novels originally published in Ireland in the years between the passing of the Act of Union and the revival of the Irish publishing industry in the 1830s. The Wild Irish Girl takes elements from these earlier fictions - an Irish setting, religious difference, Gothic plots and an interest in a contested past - and combines them with Owenson’s extensive knowledge of antiquarian debates and contemporary politics to produce a national romance. A young English man is banished to his father’s estates in Ireland. There he learns the history of those lands, which have come into his family as a result of the Cromwellian conquest. He falls in love with the daughter of the Gaelic family dispossessed by his ancestors and their marriage serves to allegorise a happier future for a divided Ireland, as well as more immediately reminding readers of the recent Union between Great Britain [414] and Ireland. The longevity of this plot (up to and including contemporary troubles romances and films like Neil Jordan’s The Crying Game) suggests resilience and flexibility; and should remind us also of the many possible meanings of Owenson’s narrative manoeuvres. / The national tale’s distinctive generic qualities are the result of efforts by (chiefly Irish female writers to give fictional shape to an interrelated set of concerns, including history, property and national conduct. The national tale combines elements of feminist fictions of the 1790s with bardic verse, allegory and the contemporary novel of courtship and companionate marriage. From 1808 to 1814 may be seen as the great years of the national tale and the period evidences a set of titles that prove the instant marketability of The Wild Irish Girl formula. [...]’. (pp.414-15.) [Cont.]

Claire Connolly (‘Irish Romanticism, 1800-1839’, 2006) - further.: ‘Owenson’s later Irish novels (O’Donnel, 1814), Florence Macarthy, 1818) and The O’Briens and The O’Flaherties (1824) move out of the mode of fatal sincerity and into what Ina Ferris has identified as an obliquely angled and shape-changing mode of address. [Ferris, The Romantic National Tale and the Question of Ireland (Cambridge UP 2002), p.76.] Owenson (by now Lady Morgan, thanks to her marriage to the physician of her Whig patrons, Lord and Lady Abercorn) creates in these novels a series of highly artificial and ‘performative’ heroines, who translate a need for secrecy (demanded by even the most blameless of public causes) into disguise, theatricality and display. Owenson’s interest in powerful women sequestered within convents or other all-female spaces allows us to connect her writings to later fictions by Kate O’Brien and Julia O’Faolain. Like them, she combines a strong interest in romance with narrative strategies that move ‘on the diagonal’, as Ferris puts it, and address history aslant. Her later Irish novels show evidence of a sustained engagement with recent Irish history, in particular the turbulent decades of her own youth. The 1780s and 1790s are presented almost as a series of tableaux, connected via a series of cinematic fades back into the sixteenth century. (p.415; for longer extracts, go to RICORSO Library, “Irish Critical Classics”, via index or direct.)

Kathryn Kirkpatrick, Introduction to The Wild Irish Girl [Oxford Classics] (Oxford: OUP 1999): ‘[... B]y constructing for herself the role of professional writer, Owenson crossed boundries of class and gender, rescuing herself and her immediate family from penury and enjoying a professional and economic success usually reserved for men. Moreover, it was through her fiction, and particularly The Wild Irish Girl, that Sydney Owenson also constructed a cultural identity. In her first Irish novel she created a Gaelic character who provided her with another public role she would perform for much of her life. Her name was Glorvina. / The Wild Irish Girl thus provided both Ireland and Sydney Oweson with myths of origins. Intended to persuade English readers that the true Irish were Gaels, Owenson’s novel along with [ix] its extensive footores provided instruction in the Irish language, music, history, and legend. And just as Owenson suppressed the Anglo-Irish elements in her prepresetnation of Irish identity, so she suppressed Englishness in the representation of her own.’ (pp.ix-x.) [Cont.]

Kathryn Kirkpatrick, Introduction to The Wild Irish Girl (1999) - further: ‘[...] Owenson sets up a dramatic contrast between north and south, Scots and Irish, by comparing one evening during the journey spent at the home of an Irish family on Connaught and another spent at an inn in Ulster. The priest prepares Horatio for the Irish hospitality he will receive in Connaught, observing “We poor Irish ... find the unrestrained freedom of an inn not ony in the house of every friend, but of every acquaintance however distant.” (p.180; OUP edn.) Indeed, at the home of their Irish hosts, Horatio and the priest are greeted with the warmth of “ten thousand welcomes”, fed “plenteous dinner”, and entertained with music and conversation; “the ease of the guest seemed the pleasure of the host” (pp.194-95). But in Uster the narrative instructs readers in a different history and a different culture. Describing the six counties of the north as “a Scottish colony” settled by favourites of James I, the priest portrays the Scots character as one in which “the ardor of the Irish constitution seems abated, if not chilled. Here the cead-mile falta of Irish cordiality seldom lends its welcome home to the stranger’s heart.” (p.198.) Bereft of “convivial pleasures”, Ulster is instead presented as a region of industry and trade where material prosperity is had at the expense of heartflet sociality. As if to give the northern character visual representation, Horatio and the priest conclude their trip to the north with a visit to one of the last Irish bards, the mon wi the twa heads, so named because of an enormous growth on the back of his head. (Owenson describes the wen in a footnote to her text as “hanging over his neck and shoulders, nearly as large as his head.” p.201.) Father John laments the impoverished circumstances of this old Irishman who sleeps in bed with his harp: “Who would suppose that that wretched hut was the residence of one of that order once so revered among the Irish” (p.203.) Not only are the values of true Irishmen neglected in this region, but the representatives of authentic Gaelic culture languish and even, perhaps, mutate. Thus, Owenson’s narrative trip to Ulster closes with a monstrous and pathetic human manifestation of the cultural graft with which the Prince of Inismore heralds the journey. Readers are let to suppose that his Irish generosity gets the better of his judgemnt in his assessment of the Scots.’. [Cont.]

Kathryn Kirkpatrick, Introduction to The Wild Irish Girl (1999) ‘Contemporary scholars have criticised this kind of essentialist thinking about national identity in The Wild Irish Girl, and they have [xiii] linked such thinking with the Troubles in the North. Elmer Andrews has argument that in the nationalist discourse of the 1980s in Belfast or Derry[:] “You hrear played out ... the old clamant sound-track of Romantic Ireland, the old ancestral myth of origin, the spiriutal heroics ... expressive of the Hegelian notion of an inner essence or spirit whcih has lent itself to and become the justification for nothing less than a declaration of war. For at the heart of the conflict in the North ... is a political theology, the paradigms of which were laid down in Lady Morgan’s originative literary steoreotyping of a myth of Irishness. (Andrews, “Aesthetics, Politics, and Identity: Lady Morgan’s The Wild Irish Girl”, in Canadian Journal of Irish Studies, 12, 1987, p.8.) But of course Lady Morgan did not create Irish stereotypes. The English had long been in that business. Rather, she sought to make the stereotypes more positive. [..]’ (pp.xiii-iv; available at Google Books - online).

[ top ]

Rolf & Magda Loeber, A Guide to Irish Fiction, 1650-1900 (Dublin: Four Courts Press 2006) - Introduction: ‘At the same time, Ireland shared with other European nations the emergence of the ‘ national tale’. The earliest known Irish instance was Sydney Owenson’s (later Lady Morgan) The wild Irish girl. A national tale which appeared in 1806. Within the next four decades, the epithet national was attached to the title of an Irish work only six times. Other books advertising themselves as Irish novels and tales (without the adjective “national”) emerged subsequently. In fact, one of the most surprising facts is that novels referring to Ireland or the Irish as advertised by their title increased significantly during the nineteenth century [...]. [Seamus] Deane, in discussing Irish national fiction, emphasizes that the emergence of Irish national tales rested on three claims, that a) Ireland was a culturally distinct nation; b) it had been mutilated beyond recognition by British colonialism; and c) it could nevertheless rediscover its lost features and thereby recognize once more its true identity’. (Deane, Strange Country: Modernity and Nationhood in Irish Writing Since 1790, Clarendon Press 1997, p.53; see also Deane, Short History of Irish Literature, London: Hutchinson 1986p.62ff.; Loebers, op. cit., p.lxii.) [Cont.]

Rolf & Magda Loeber (A Guide to Irish Fiction, 1650-1900, 2006) - cont.: ‘Thus, a century prior to Irish independence from Britain, various notions of Irishness developed through the medium of fiction. Curiously, however, Lady Morgan’s national tales appear to have addressed an English readership, [ 80] were never reprinted in Ireland and, therefore, may have reached only a small Irish readership, who would have had to rely on her English-published works. Remarkably, it was an English and not an Irish publisher - Henry Colburn - who issued in 1834 a fiction series with the title Irish National Tales, which consisted of books produced from the remainder sheets of earlier editions of Irish novels. Most [lxii] Irish literature with nationalistic themes was not published in Ireland but was produced by London printing presses and financed by English publishing houses [ref. here to Section V of the Guide]. This coincided with a shift by Irish authors wishing to address English rather than Irish readerships about matters Irish [...]’ (Ibid., pp.lxii-iii.) See also remarks on J. W. Croker’s critique of Owenson [Lady Morgan], under Croker, q.v., infra.

Terry Eagleton, Introduction to the Novel (Wiley Blackstock 2005): ‘[Walter Scott’s] Waverley attracted the kind of celebrity that even today’s literary superstars would envy. Yet behind Waverley - the work of an author who pokes fun at the excesses of Gothic, sentimental, chivalric and female fiction - lies an obscure novel by an Anglo-Irish Gothic author, Charles Maturin’s The Milesian Chief. Behind it more generally lies a hinterland of women writers, so-called national tales, romances, folk material and nationalist antiquarian research from which the reputable Sir Walter derived rather more than he was always prepared to acknowledge. In this sense, the canonical had its roots in the non-canonical, as is often the case. Irish women like Sydney Owenson (Lady Morgan), Maria Edgeworth and others were intensively involved in fiction about national and cultural identity, and its complex relations to gender, in a way which gives the lie to the prejudice that while the expansively “masculine” Sir Walter wrote novels about the public world, female writers were all as domestically restricted as a Jane Austen. The novel, Sydney Owenson remarked, is “the best history of nations”. Cultural nationalism at the time of Scott and Austen involved myth and fantasy, popular customs and sentiments, the exploration of identity as well as the struggle to tell your own story. It was thus the kind of politics which lent itself particularly well to the novel, which also trades in such matters. At the same time, however, partly because of this colonial turbulence, there was a need for the British state to consolidate its power; and the novel played an indirect role in this project as well. If it was a vehicle of radical, Gothic, colonial, abolitionist or feminist dissent, it was also a sturdy instrument of political authority. It could play an invaluable role in defining the true meaning of Englishness or Britishness, at just the moment when these notions was coming under fire from cultural nationalisms at home and political revolutions abroad.’ (Kindle edition.)

Terry Eagleton, Heathcliff and the Great Hunger: Studies in Irish Culture (London; Verso 1995): ‘The problem of form [...] is also a problem of politics. Two quite separate discourses, one romantic, the other realist, inhabit Morgan’s text without ever fruitfully interlocking; and since romance signifies an ideal, and realism an actual ruling class, this shift and clash of linguistic registers is the site of a genuine ideological dilemma.’ (p.179; quoted in Joep Leerssen, Remembrance and Imagination: Patterns in the Historical and Literary Representation of Ireland in the Nineteenth Century Cork UP/Field Day 1996, pp.51-52.)

[ top ]

Quotations| Commentary | Quotations |

| Irish gentry?: Epigraph to O’Donnel: a National Tale [1814] rev. edn. Coburn 1835): ‘Art thou a gentleman? What is thy name? Discuss!’ - Shakespeare. |

| Irish fiction: ‘A novel is especially adapted to enable the advocate of any cause to steal upon the public, through the by-ways of the imagination, and win from it sympathies what its reason so often refuses to yield to undeniable demonstration.’ (Quoted in Rolf & Magda Loeber, A Guide to Irish Fiction, 1650-1900, Dublin: Four Courts Press 2006, citing Ina Ferris, The Romantic National Tale and the Question of Ireland, Cambridge UP 2002, 13.) |

| See The Wild Irish Girl (1806) - full-text copy in RICORSO Library, “Irish Classics” - as infra |

|

||

| Works | ||

| The Wild Irish Girl (1806) Patriotic Sketches written in Connaught, (1807) O’Donnel: A National Tale (1814) |

Lady Morgan’s Memoirs Lady Morgan’s “Journal” Passages from My Autobiography (Preface) |

|

| Remarks | ||

| Act of Union “Rulers of the earth” “Era of transition” Farewell to Ireland |

||

|

||

| “Kate Kearney” (Ballad of 1805) | ||

|

||

|

[ top ]

The Wild Irish Girl (1806): ‘To confess the truth, I had so far suffered prejudice to get the start of inquiry, that I had almost assigned to these rude people, scenes appropriately barbarous; and never was I more pleasantly astonished, than when the morning’s dawn gave to my view one of the most splendid sights in the scene of picturesque creation I had ever beheld, or even conceived - the bay of Dublin [...] The springing up of a contrary wind kept us for a considerable time beating about the coast: the weather suddenly changes, the rain poured in torrents, a storm arose, and the beautiful prospect, which had fascinated our gaze, vanished in mists of impenetrable obscurity.’ (Vol. 1, pp.33-34; quoted in Siobhán Kilfeather, ‘Origins of the Irish Female Gothic’, in Bullán, Autumn 1994, 1994, p.39.)

Lay of an Irish Harp (1807) - in which the title-poem incls. the lines: ‘Why sleeps the Harp of Erin’s Pride? / Why with’ring droops its shamrock wreath? / Wy has that song of sweetness died / Which Erin’s Harp along can breathe?’ (Quoted in Joep Leerssen, Remembrance and Imagination, [... &c.] 1996, p.59 - noting that it ‘closely foreshadows Moore’.)

| Epigraph |

|

|

—Fanio Della Uberti’s Travels through Ireland / in the 14th century |

| Introductory Letters |

| The Earl of - M to the Hon. Horatio M - , King’s Bench. |

Castle M- , Leicestershire, Feb. - , 17-- |

| ”If there are certain circumstances under which a fond father can address an imprisoned son, without suffering the bitterest heart-rendings of paternal agony, such are not those under whch I now address you. To sustain the loss of the most precious of all human rights, and forfeit our liberty at the shrine of virtue, in defence of our country abroad, or of our public integrity and principles at home, brings to the heart of the sufferer’s dearest sympathizing friend, a soothing solace almost concomitant to the poignancy of its afflictions, and leaves the decision difficult, whether in the scale of human feelings, triumphant pride or affectionate regret preponderate. [iii; ...] |

[ The father offers to rescue the son imprisoned for a debt that he incurred through an illicit relationship with Lady C- and the blackmail of her husband; he agrees to pay his debts and release him from the King’s bench [debtor’s gaol] on condition that he goes to the family estate in Connaught where the father is also retiring to mend his damaged fortune. The son, Horatio, now communicates with a friend explaining his affair with Lady C- and his father’s resolution to reform him and set him again on the path of legal studies and instill in him the prudence of his older but less brilliant brother. In all of this, the son shows himself to the victim of ‘the moment of ardent sensibility [...] when woman becomes the sole spell which lures us to good or ill, and when her omnipotence, according to the bias of her own nature, and the organization of those feelings on which it operates, determines in a certain degee our destiny through life - lead the mind through the medium of the heart to the noblest pursuits, or seduces it through the medium of the passions to the basest career.’ (p.xii.) ] |

| ‘Had he banished me to the savage desolations of Siberia, my exile would have had some character; had he even transported me to the South Sea Island, or thrown me into an Exquimaux hut, my new species of being would have been touched with some interest, for in fact, the present relaxed state of my intellectual system requires some strong transition of place circumstance, and manners, to wind it up to its native tone, to rouse it to energy, or awaken it to exertion. / But sent to a country against which I have a decided prejudice - which I suppose sem-barbarous, semi-civilized [xiii]; has lost the strong and hardy features of savage life, without acquiring those graces which distinguish polite society - I shall neither participate in the poignant pleasure of awakened curiosity and acquired informatioin, nor taste the least of those enjoyments which courted y acceptance of my native land.’ ([Letter “To J.D. Esq. M.P. / Holyhead. xiii-xiv.) |

[ The young man has been expressly enjoined by his father to return to legal studies and to abjure belles lettres and chemistry. He now asks his friend to send Italian crayons for his servant Laval, who ‘entertain[s] no less prejudice against this country than his master’ (xiv) and to send him a thermometer (otherwise ‘a Fahrenheit’) so that ‘I may bend the few coldly mechanical powers left to me, to ascertain the temperature of my wild western territories, and expect my letters from thence to be only filled with the summary results of meteoric instrument, and synoptic views of common phenomena. / Adieu. / H. M.” (p.xv.) ] |

| [ Note that H.M. is Horatio Mortimer. ] |

|

| [ Digital copy of 1808 Boston edition at Google Books - online. ] |

The Wild Irish Girl (1806), Horatio: ‘Whenever the Irish were mentioned in my presence, an Esquimaux group circling round the fire blazing to dress a dinner or broil an enemy, was the image which presented itself to my mind’ (Vol. 1, p.36; The Wild Irish Girl, Wolff edn., Garland, 1979.)

‘Behold me, then, buried amidst the monuments of past ages! - deep in the study of language, history, and antiquities of this ancient nation - talking of the invasion of Henry II, as a recent circumstance - of the Phoenician migration hither from Spain, as though my grandfather has been delegated by the Firbalgs to receive the Milesians on their landing.’ (Vol. 2, p.8-9.)

[Father John:] ‘Ireland, owing to its being colonised from Phoenicia, and consequent early introduction of letters there, was ... esteemed the most enlightened country in Europe.’ (Vol. 2, p.69.)

The Wild Irish Girl (1806): ‘It has been the fashion to throw an odium on the modern Irish, by undermining the basis of their ancient history, and vilifying their ancient national character.’ (Ibid., Vol. 3, note on p.14; the foregoing passages quoted in Elizabeth Butler Cullingford, ‘British Romans and Irish Carthaginians: Anticolonial Metaphor in Heaney, Friel and McGuinness’, in PMLA, March 1996, pp.222-36.)

‘Mountain rising over mountain, swelled like an amphitheatre [...] Allwas silent and solitary - a tranquillity tinged with terror, a sort of “delightful horror”, breathed on every side’; ‘Surely, Fancy, in her boldest flight, never gave to the fairy vision of poetic dreams, a combination of images more poetically fine, more strikingly picturesque, or more impressively touching.’ [...] ‘What a picture [...] What a captivating, what a picturesque faith" [...] Who cold not become its proselyte, where it not for the stern opposition of reason - the cold suggestion of Philosophy!’ [...] ‘No adequate version of an Irish poem can be given; for the peculiar construction of the Irish language, the felicity of its epithets, and the force of its expression, bid defiance to all translation.’ (Pandora Edn., 1986, p.37, 41 & 82; all quoted in quoted in Richard Pine, The Disappointed Bridge: Ireland and the Post-Colonial World, Cambridge Scholars Publishing 2014, pp.345-46.)

The Wild Irish Girl (1806): ‘[...] we trace the spirit of Milesian poetry to a higher source than the spring of Grecian genius; for many figures in Irish song are of oriental origin; and the bards who ennobled the train of our Milesian founders, and who awakened the soul of song here, seem, in common with the Greek poets, “to have kindled their poetic fires at those unextinguished lamps which burn within the tomb of oriental genius”. Let me, however, assure you, that no adequate version of an Irish poem can be given; for the peculiar construction of the Irish language, the felicity of its epithets, and force of its expressions, bid defiance to all translation’ (OUP Edn., 1999, pp.91-2.)

‘Once we were every where, and by all, justly famed for our patriotism, ardor of affection, love of letters, skill in arms and arts, and refinement of manners; but no sooner did there arise a connexion between us and a sister country, than the reputed virtues and well-earned glory of the Irish sunk at once into oblivion [..] Thus it should seem, that when the bosom of national freedom was rent Asunder, the national virtues which derived their nutriment from its source sunk into the abyss; while on the barren surface which, overs the wreck of Irish greatness, the hand of prejudice and illiberality has sown the seeds of calumny and defamation, to choak all up those healthful plants, indigenous to the soil, which still raise their oft-crushed heads, struggling for existence, and which, like the palm-tree, rise in proportion to those efforts made to suppress them.’ (Idem., 1999 edn., pp.177-78; the foregoing quoted in Susanne Hagemann, ‘Tales of a Nation: Territorial Pragmatism in Elizabeth Grant, Maria Edgeworth, and Sydney Owenson’, in Irish University Review, Autumn/Winter 2003, pp.273 & 275).

[Horatio:] ‘A thousand times since my arrival in this trans-mundane region, I have had reason to feel how much we are the creatures of situation; how insensibly our minds and our feelings take their tone from the influence of existing circumstances. You have seen me frequently the very prototype of nonchalance, in the midst of a circle of birth-day beauties, that might have put the fabled charms of the Mount Idea triumviri to the blush of inferiority. Yet here I am, groping my way down the dismantled stone stairs of a ruined castle in the wilds of Connaught, with my heart fluttering like the pulse of green eighteen in the presence of its first love, merely because on the point of appearing before a simple rusticated girl, whose father calls himself a prince, with a potatoe ridge for his dominions! O! with what indifference I should have met her in the drawing-room, or at the Opera! - there she would have been merely a woman! - here, she is the fairy vision of my heated fancy.’

Preface of 1835 Colburn Rev. Edn.: ‘At the moment when The Wild Irish Girl appeared it was dangerous to write on Ireland, hazardous to praise her, and difficult to find a publisher for an Irish tale which had a political tendency. For even ballads sung in the streets of Dublin had been denounced by government spies, and hushed by Castle “sbirri” because the old Irish refrain of Erin go bragh awakened cheers of the ragged, starving audience.’ (Quoted in Mary Campbell, Lady Morgan: The Life and Times of Sydney Owenson, London: Pandora 1988, p.3.)

[ top ]

| Topical Extracts from The Wild Irish Girl (1806) |

| Catholicism: ‘What a religion is this! How finely does it harmonize with the weakness of our nature; how seducingly it speaks to the senses; how forcibly it works on the passions; how strongly it seizes on the imagination; how interesting its form; how graceful its ceremonies; how awful its rites. - What a captivating, what a picturesque faith! Who would not become its proselyte, were it not for the stern opposition of reason - the cold suggestions of philosophy!’ (The Wild Irish Girl, Letter V.) |

| Irish music: |

| ‘“Our national music,” she returned, “like our national character, admits of no medium in sentiment: it either sinks our spirit to despondency, by its heart-breaking pathos, or elevates it to wildness by its exhilarating animation. “For my own part, I confess myself the victim of its magic - an Irish planxty cheers me into maddening vivacity; an Irish lamentation depresses me into a sadness of melancholy emotion, to which the energy of despair might be deemed comparative felicity.”’ (Ibid., Letter VI.) |

| Sanguinary Irish?: ‘To endeavour to efface from the Irish character the odium of cruelty; by which the venom of prejudiced aversion has polluted its surface, would be to retrace a series of complicated events from the first period of British invasion to a recent day. [...] Had the Historiographer of MONTEZUMA or ATALIBA defended the resistance of his countrymen, or recorded the woes from whence it sprung, though his QUIPAS was bathed in their blood, or embued with their tears, he would have unavailingly recorded them; for the victorious Spaniard was insensible to the woes he had created, and called the resistance it gave birth to CRUELTY. But when nature is wounded through all her dearest ties, she must turn on the hand that stabs, and endeavour to wrest the poniard from the grasp that aims at the life- pulse of her heart. And this she will do in obedience to that immutable law, which blends the instinct of self-preservation with every atom of human existence. [... T]he national character of Ireland never deserved the disgraceful epithets of sanguinary: had we affixed it to the transactions of the civil war, we should only conclude that, roused by a series of wrongs too great for human patience, a desperate and desponding people had submitted, in a wild paroxysm of rage, to the fierce impulse of nature on their untutored minds, and sacrificed to their feelings those men whom they regarded as the authors or the instruments of their misfortunes; even on this hypothesis, which the concurring testimony of history and probability compel us to reject, we might palliate, though we could not justify, the frenzy.’ (Ibid., Letter XXV.) |

| —See full-text copy of The Wild Irish Girl (1806) in RICORSO Library, “Irish Classics” - as attached. |

Patriotic Sketches written in Connaught, (1807): ‘A passion for enjoying a twofold existence, independent of actual being, of tracing back genealogical honours, and anticipating a perpetuated life in the hearts of those they leave behind; is a passion incidental to the native Irish character of every rank; and though in the world’s language it may be deemed a romantic passion, yet romance, like heroism, is never a national trait of a corrupt or base people [...] (Vol. II, 18-19; quoted in Joep Leerssen, Remembrance and Imagination: Patterns in the Historical and Literary Representation of Ireland in the Nineteenth Century [Field Day Monographs: Critical Conditions 4], Cork UP 1996, p.11.)

[ top ]

O’Donnel: A National Tale (1814) - Preface: ‘Literary fiction, whether directed to the purpose of transient amusement, or adopted as an indirect medium of instruction, has always in its most genuine form exhibited a mirror of the times in which it is composed: reflecting morals, customs, manners, peculiarity of character, and prevalence of opinion. Thus, perhaps, after all, it forms the best history of nations, the rest being but the dry chronicles of facts and events, which in the same stages of society occur under the operations of the same passions, and tend to the same consequences.

But, though such be the primary character of fictitious narrative, we find it, in its progress, producing arbitrary models, dervied from conventional modes of thinking amongst writers, and influenced by the doctrines of the learned, and the opinions of the refined. Ideal beauties, and ideal perfection, take the place of nature, and approbation is sought rather by a description of what is not, than a faithful portraiture of what is. He, however, who soars beyond the line of general knowledge, and common feelings, must be content to remain within the exclusive pale of particular approbation. It is the interest, therefore, of the novelist, who is, par etat, the servant of the many, not the minister of the FEW, to abandon pure abstractions and “thick coming fancies,” to philosophers and to poets; to adopt, rather than create; to combine, rather than invent; and to take nature and manners for the grounds and groupings of works, which are professedly addressed to popular feelings and ideas. / Influenced by this impression, I have for the first time ventured on that style of novel, which simply bears upon the “flat realities of life.” [...]’

I discovered, far beyond my expectation, that I had fallen upon “evil men, and evil days;” and that, in proceeding, I must raise a veil which ought never to be drawn, and renew the memory of events which the interests of humanity require to be for ever buried in oblivion. / I abandoned, therefore, my original plan, took up a happier view of things, advanced my story to more modern and more liberal times, and exchanged the rude chief of the days of old, for his polished descendant in a more refined age: and I trust the various branches of the ancient house with whose name I have honored him will not find reason to disown their newly discovered kinsman. [Vol. 1, pp.x-xi; quoted in Joep Leerssen, Remembrance and Imagination [... &c.], Field Day 1996, p.43.] (See longer extract from the Preface - attached.)

[ top ]

Memoirs [on The Wild Irish Girl]: ‘Graves were still green, where the victims of laws uselessly violated were still wept over by broken hearts; no work ... of fictional narrative, founded on national grievances, and borne out by historic fact had yet appealed to the sympathies of the general reader, or found its way to the desultory studies of domestic life! The Wild Irish Girl took the initiative; in an experiment since carried out to perfection by abler talents, and it was no small publishing moral courage on the part of the most fashionable English bibliophilist of the day.’ (Quoted in Mary Campbell, Lady Morgan, 1988, p.61.)[ top ]

Memoirs [writing in 1853 on the post-Famine diaspora]: ‘Fiction has nothing more pathetic than that great melodramatic tragedy now performing on the shores of Ireland - The Celtic Exodus. The Jews left a foreign country - a house of bondage; but the Celtic exodus is the departure of the Irish emigrants from the land of their love - their inheritance - and their traditions - of their passions and their prejudices; with all the details of wild grief and heart-rending incidents - their ignorance of the strangers they are going to seek - their tenderness for the objects they are leaving behind. Their departure exceeds in deep pathos all the poetical tragedy that has ever been presented on the stage, or national novelists have ever depicted in their volumes.’ (Memoirs, II, p.523; quoted in Patrick Sheeran, “The Novels of Liam O’Flaherty: A Study in Romantic Realism”, Ph.D., UCG 1972, p.179.)

Journal [Self-portrait]: ‘[...] caricatured to the utmost; abused, calumniated, misrepresented, flattered, eulogised, persecuted; supported as party dictated or prejudice permitted; the pet [69] of the Liberals of one nation, the bête-noire of the ultra set of anther; the poor butt that reviewers, editors, and critics have set up ... ’ (Quoted in Elizabeth Bowen, The Shelbourne, 1951, pp.69-70.)

Passages from My Autobiography (1859) - Preface (pp.[v]-xi): "The following pages are the simple recors of a transition existence, socially enjoyed, and pleasantly and profitably occupied, during a jounrey of a few months from Ireland to Italy. / They were not written for the special purpose of any work, but were mere transcripts of circumstances incidental to that journey, which was delayed in its progress by all that could interest the feelings or gratify the mind. [...] [v] during what was then deemed a perilous journey to Italy, I followed my old habit of occasional diary; and one still older and dearer, a constant correspondence with my dear and only sister. These homestead leatters - these rapidly-scrawled diaries, written à saute et à gambade, form, I believe, the material portion of this volume. The more spirituel and interesting part will be found in the letters of some of most eminent men and women of the times they illustrated by their genius their worth, their cultivation of letters, and their love of liberty. / Egotism is a sin of autobiography, and vanity naturally takes the pen to trace its dictation. They vanity, or, to give its better name, the pride with which I give these letters to the publish with the permission of, alas! the few survivors, and the concurrence of those most interested in their posthumous reputation, is attributable to the enduring friendship and support with which the writers honoured me, foremost among whom I place General La Fayette, Baron Dénon, and Catherine, Countess of Charleville. / The genuiness of the little work in this irrefragable testimony of the autograph letters, from which uncopied they have been printed amongst the rest of my letters to my sister, which, frivolous and domestic as women’s confidential letters generally are, convey some idea of the habits, times, and manners when they were composed. There they are! Records of the passage of more years than I am willing to reveal, with their horrible postmarks [...].’ [She here mentions her brother-in-law Arthur Clarke as taking on the transcription due to her poor health and copies his letter in full asking her to write something to compare with Moore’s Memoirs: ‘Every page I read makes me wish that our own Wild Irish Girl would sit down and dictate her own memoirs (if she cannot write them) which nobody living but herself can do.’] (viii-ix.)’

Act of Union: ‘A few days back, I met with two peasants who were making compaints of the oppression they endured. A gentleman asked them if they thought they were worse off since the union. They replied, “they had never heard anything about the union, and did not know what it meant.” After some further questions, they were asked, “if they did not know that there was now no Irish parliament.” They replied, that all they had heard was, that the parliament-books were sent away, and that the good luck of the country went with them. Sofull is the heart of the Irish peasant with his own grievance, and so little is his head troubled about public affairs.’ (Patriotic Sketches of Ireland, Written in Connaught, 2 vols. London 1807, I, 121n.; quoted in Claire Connolly, ‘Writing the Union’, in Dáire Keogh & Kevin Whelan, eds., Acts of Union: The Causes, Contexts and Consequences of the Act of Union, Dublin: Four Courts Press 2001, p.174.) Further, ‘for it was ever, as in is now, the singular destiny of Ireland to nourish within her own bosom her bitterest enemies, who, with a species of political vampyrism, destroyed that source from whence their own nutriment flowed’ (Ibid., Vol. I, pp.111-12; Connolly, op. cit., 2001, p.185.)

Rulers of the earth - writing from chez the Abercorns at Baron’s Court: ‘I hear of nothing but politics and the manner in which things are considered gives me a most thorough contempt for the “rulers of the earth”. I am certain that the country, its welfare or prosperity never for a moment take a part in their speculation; it is all a little miserable system of self interest, paltry distinctions of private pique, and personal ambition.’ (Letter [to Alicia Le Fanu]; quoted in Mary Campbell, op. cit., 1988, p.104.)

Era of transition: ‘We are living in an era of transition. Changes moral and political are in progress. The frame of the constitution, the frame of society itself, are sustaining a shock, which occupies all minds, to avert or modify. [...] Under such conditions there is no legitimate fiction and no legitimate drama.’ (Dramatic Scenes from Real Life, 2 vols., London 1883, Vol. 1, pp.iv-v; quoted in David Lloyd, Anomalous States, 1993, p.134, and cited in Conor McCarthy, Modernisation, Crisis and Culture in Ireland 1969-1992, Four Courts Press 2000, p.125 [no primary source given].)

Farewell to Ireland: ‘You [compatriots of all persuasions] have always slighted and often persecuted me, yet I worked in your cause, humbly, but earnestly. Catholic Emancipation is carried! It was an indispensable act - of what results, you fickle Irish will prove in the end. To predicate would be presumptuous, even in those who know you best. Creatures of temperament and temper, true Celts, as Caesar found your race in Gaul, and as I leave you, after a lapse of two thousand years.’ (Memoirs, Autobiography, Diary and Correspondence, ed. W Hepworth Dixon, II, p.148; quoted in Patrick Rafroidi, Irish Literature in English, The Romantic Period, 1789-1850, Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1980, Vol. 1, p.108 [as supra].)

Irish history: ‘I have nothing more to add than that my story, strange and improbable as it may appear, belongs to the history of a long disorganised country.’ (Quoted in Terry Eagleton, ‘Form and Ideology in the Anglo-Irish Novel; in Búllan, I (1994), p.24 [cited in ILS review, Fall 1994).

Woman defined: ‘[A]n almost innate propensity to physical and moral beauty, an instinctive taste for the fair ideal, and a lively and delicate susceptibility to ardent and tender impressions.’ (Preface, Woman, or Ida of Athens.)

St. Kevin: Patrick Rafroidi writes, ‘Lady Morgan, one of many to make sarcastic comments on St Kevin’s bed, mistook her French (matelas), in Landscape Illustrations of Moore’s Irish Melodies, [and hence] wrote, ‘Je n’aimerai [sic] pas coucher sur un matelot [sic] si dur!’ (Rafrioidi, Irish Literature in English [ ... &c.] 1980, Vol. 2, p.188).

[ top ]