Life

1746-1818 [Baronet; pseud. “Veridicus”; var. ?1745; 1757]; eldest son and heir of Christopher Musgrave of Tourin, Co. Waterford, and thus a member of minor gentry of the county; his mother was an Usher of Ballintalor; elected MP for Lismore, 1778-1801; and created first baronet Dec. 1782; appt. high sheriff of County Waterford and executed the sentence of flogging a Whiteboy miscreant when no one else could be found to do it, Sept. 1786; issued Letter on the Present Situation of the Public Affairs (1795), warning of Defenderism, the United Irish movement and impending rebellion; actively supported the Orange Order (‘many gentlemen of considerable talent placed themselves at its head to give the institution a proper direction’, Mem., p.72) and professed himself a ‘warm advocate’ of the Union (Letter to Bishop Percy, Jan. 1799); his virulently anti-Catholic Memoirs of the Different Rebellions in Ireland (1801) was largely based on information solicited from the gentry of Wexford such as Lenox-Conyngham and was dedicated to Lord Cornwallis, Viceroy but repudiated by him; it ran to three edns. during 1801-1802, and was answered by Bishop Caufield, in defence of the Catholic hierarchy occasioning a riposte from Musgrave as Observations on the Reply [... &c.] (1802); supposedly wounded in a duel with a certain William Todd Jones arising from remarks in his Memoirs of the Irish Rebellion alleging United Irish sympathies on his part; the Memoirs includes a virulent attack on Edmund Burke’s purported encouragement of Catholics considered as enemies of the British state, and blames liberal Protestants for creating the occasion for the Rebellion, especially through Catholic relief measures of 1792 and 1793 - together with the sponsorship of ‘infidel’ Presbyterians in Ulster; answered Francis Plowden’s Historical Review of the State of Ireland (1803) with his own Strictures (1804) and was answered in turn; castigated the Catholic clergy as enemies of the ‘glorious constitution’ of the Hanoverian Protestant state and is regarded as an ultra-Protestant ideologue by modern historians; his To the Magistrates, the Military, and the Yeomanry of Ireland (1798), published under the pseudonym 'Callimus', seeks to exonerate the government of provoking the rebellion; Musgrave claimed in Memoirs to have forewarned Bagenel Harvey (d. 28 June 1798) of the dangers to his life and property incurred by espousing republican ideals at a social encounter prior to the rebellion; in the wake of the Rebellion he is considered one of the most strenuous proponents of the Act of Union and the abolition of a separate Irish parliament and kingdom, along with with Partick Duigenan [q.v.]; his Memoir considered prejudice and misleading by nationalists incl. John Mitchel [q.v.] who ‘purposely excluded’ that work as being ‘wholly untrustworthy’ from his account of 1798 in his edition and continuation of MacGeoghegan’s History of Ireland (1869) - and followed in that view by the DNB article which deems his Memoirs to be ‘steeped in anticatholic prejudice as to be almost worthless historically’; his reputation continues to be that of a sectarian writer on the side of the Protestant ‘establishment’ - a word used equally for the church and the state as joint arms of the British Constitution. DIW ODNB RAF |

|

||||||||||||

[ top ]

Works

|

| Reprint: |

|

Bibliographical details

Ist edition: Memoirs of the Different Rebellions in Ireland from the arrival of the English: with a particular detail of That Which Broke Out the XXIIId of May, MDCCXCVIII [23rd May 1798]; with the History of the Conspiracy which Preceded It and the Characters of the Principal Actors in It. Compiled from Original Affadavits and Other Authentic Documents and illustrated with Maps and Plates by Sir Richard Musgrave, Bart., Member of the late Irish Parliament [epigraphs from Shakespeare and Livy]; Dublin: printed by Robert Marchbank for John Millikin, 32, Grafton-Street [Dublin] and John Stockdale, Piccadilly, London, 1801), x, 636pp. + Appendices I-XXI, 166pp + Index [8pp.]Il. Ills: Frontis. port. Lord Lake; 9 fold. maps [e.g., A map of New Ross occupies a place between p.406 & 407]. Ded. Charles Marquis Cornwallis, Lord Lieutenant General, and General Governor of Ireland [signed Dublin March 1801], [v]-x. Contents [xi]-xii; facing, bound-in map of Ireland elucidating the Irish Rebellion of 1798 [xii]; Memoirs [... &c.], [1]-635pp.; Account of the money claimed by the suffering loyalists [..] appointed by act of parliament for compensation them [by county; in total £82,3517.6.4.] [p.636]. [Appendices:] Appendix No 1 pp.[1]-8 [sects. 1-8]; No. II pp.8-9; No. III, pp.10-12; No. III, p.12; No. 5, pp.12-, No. 6, p.13-15; No. VII, pp.1517; No. VIII, pp.17-20; No. IX, pp.20-22; No. X, p.22-23; No. XI, pp.24-49; No.XII, pp.50-58; No. XIII, 58-62; No. XV, pp.62-69; No. XVI, pp.69-78; No, XVII, 79-82; No. XVIII, pp.82-91; No. XIX, p.91-125; No. XX, pp.125-54; No. XXI, 154-66. [ Index [8pp.] Errata [1p.] Note: 4th edn. ed. S. W. Myers & D. E. McKnight, with foreword by David Dickson, 1995, 982pp.]

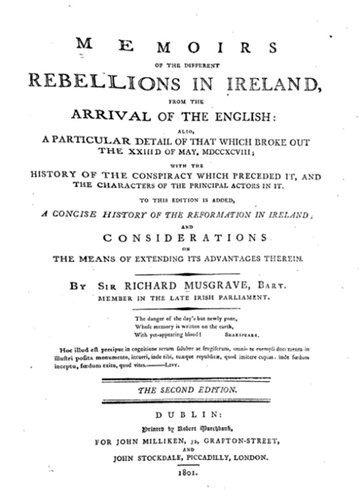

A copy of the work is available in RICORSO Library > History > Legacy - via index or as attached. Copies also available there as .doc & .pdf. 2nd Edition: Memoirs of the Different Rebellions in Ireland, from the Arrival of the English; also, A Particular Detail of That Which Broke Out the XXIIId of May, MDCCXCVIII [23rd May 1798]; with the History of the Conspiracy which Preceded It and the Characters of the Principal Actors in It. To this Edition is Added, A Concise History of the Reformation of Ireland; and Considerations on the Means of Extending Its Advantages Therein [2nd edn.] 2 vols. (Dublin: J. Milliken; London: J. Stockdale; printed by R. Marchbank 1802).

3rd edition: Memoirs of the Different Rebellions in Ireland from the arrival of the English: with a particular detail of That Which Broke Out the XXIIId of May, MDCCXCVIII [23rd May 1798]; with the History of the Conspiracy which Preceded It, by Sir Richard Musgrave, Bart. Member of the Late Irish Parliament, in Two Volumes [vol. 1] Epigraphs from Shakespeare and Livy [as before]; The Third Edition (Printed in Dublin by Robert Marchbank, and sold by J. Archer, and other booksellers, and in London by J. Stockdale, Picadilly; G. Robinson, Paternoster Row; Messrs. Rivington, St. Paul’s Church-Yard; and by R. Faulder and Messrs. Kirby, Bond-Street), x, 636, 210. pl., 4º. Includes Preface to the Third Edition, pp[i]-xvi. Contents of the first volume conclude with the Battle of Arklow (ending p.583 with promise of an account of Vinegar Hill and the ‘massacre at Wexford. in the ensuing section - i.e., Vol. 2). [Available at Google Books - online.; copy in Museum Britannicum/British Museum BML/BL.]

Musgrave’s Memoirs (1801) - Online Musgrave’s Memoirs of the Different Rebellions [... &c.] is available at Internet Archive in various formats [online] and also at Google Books - online [2nd edn.; in part]. An MSWord copy is available at RICORSO Library > History > Legacy - [.doc & .pdf]. Note that the archaic ‘f’ font for ‘s’ has been retained in the RICORSO online copy but an atttempted edition employing modern ‘s’ has been attached to it, for all its faults. No HTML copy is available in RICORSO due to the length and editorial complexity of the task involved in generating one. (DOC, PDF and HTML copies are all between 2 and 3MB in extent and unless broken up into succeeding linked files, impractical to deliver in this internet context.

[Attrib. to Musgrave,] Strictures upon an Historical Review of the State of Ireland [by Francis Plowden]; or, A Justification of the Conduct of the English Governments in that Country, from the Reign of Henry the Second to the Union of Great Britain and Ireland (London: F.C. and J. Rivington 1804), 233pp.; Do. [rep.] (Rivington 180, 233pp.

[ top ]

See also

- James Caulfield, Bishop of Ferns.The Reply of the Right Rev. Doctor Caulfield ... and of the Roman Catholic Clergy of Wexford, to the misrepresentations of Sir R. Musgrave, Bart. [in “Memoirs of the different rebellions in Ireland, from the arrival of the English ”], ... &c. [Fourth edition] (Dublin: H. Fitzpatrick 1801), vii, 60pp. [a letter from Edward Cooke, dated Dec. 12. 1798, is printed on a separate slip pasted on p.60; BL copy.]

- [Anon.,] A Reply to a Letter from the Rev. Mr. Wilson ... To this is annexed that part of the aforesaid letter, which is here particularly refuted; and likewise one of the many solemn declarations contained in the Reply of the Catholic Bishop of Wexford, and his clergy, to the misrepresentations of Sir Richard Musgrave (Preston: W. Addison [1802]), 24pp., 8º.

- Thomas Townsend, Part of a Letter to a Noble Earl: containing a very short comment on the doctrines and facts of Sir Richard Musgrave’s quarto [i.e. “Memoirs of the different rebellions in Ireland”]; and vindicatory of the yeomanry and Catholics of the city of Cork, [by] Thomas Townsend, Member of the Irish Parliament (Dublin: P. FitzPatrick 1801), 43pp., 8º.; Do., (London: Printed by T. Collins for E. Booker 1801), 43pp., 24cm. [NLI P 1853(8)]; & Do., [another edn.] (Cork: M. Harris 1801), 8º [24cm]..

- James Gordon, ‘A Reply to the Observations of Sir Richard Musgrave, Bt.’, appended to Musgrave’s History of the Rebellion in Ireland in the Year 1798 [ ... &c.] (London: Hurst 1803).

- Francis Plowden, An Historical Letter from Francis Plowden, Esq. to Sir Richard Musgrave, Bart. (London: Published by Vincent Dowling [&c.] 1805), [2], 113pp., 1 lf. of pls., 21cm [reply to Musgrave’s Strictures].

- John Milner, An Inquiry into Certain Vulgar Opinions concerning the Catholic Inhabitants and the Antiquities of Ireland ... 2nd. edn. rev and aughmented (q.d.), and Do., Third edition ... with copious additions, including the account of a second tour through Ireland by the author, and answers to Sir R. Musgrave, Dr. Ryan, Dr. Elrington, &c. (London: Keating, Brown & Co 1810), xi, 404pp., 8º.

Note: In his Memoirs of Different Rebellions in Ireland (1801) drew up some details published in Narrative of the Sufferings and Escape of Charles Jackson [q.v.], late resident of Wexford ... (1799) concerning the events of the 1798 United Irishmen’s Rebellion. Remarks in Edward Hay’s History of the Insurrection of the County of Wexford, a.d. 1798 (1803) brought on a new edition of the Memoirs with a second part entailing a rebuttal of Hay. (See further under Hay, q.v.).

1st Edition Memoirs

of the Different

Rebellions in Ireland.

from the

Arrival of the English:

with a

Particular Detail of that which Broke Out the XXIIID of May, MDCCXCVIII;

The

History of The Conspiracy Which Preceded It

and the

Characters of the Principal Actors in it.

Compiled from

original affidavits and other authentic documents;

and

illustrated with maps and plates.

By Sir Richard Musgrave, Bart.

Member in the Late Irish Parliament.The danger of the day’s but newly gone,

Whose memory is written on the earth

With yet-appearing blood! Shakespeare.

Hoc illud eû precipue in cognitione rerum salubre ac frugiferum, omnis te exempli documenta in illustri posita monumento, intæri, inde tibi, tuæque republicæ, quod imitere capias; inde fœdum inceptu, fœdum exitu, quod vites. —Livy.

[The First Edition]

DUBLIN: FOR JOHN MILLIKEN, 32, GRAFTON-STREET,

JOHN STOCKDALE, PICCADILLY, LONDON.

1801

2nd Edition

Click on image (right) to view in separate window

Note: The copy of Memoirs of Different Rebellions in Ireland (1801) used for for the digital edition at Internet Archive contains three glued-in newspaper cuttings from the Times. The first, dated ‘May 1802’ by hand, gives an account of a duel between Musgrave and a certain William Todd Jones which took place on Rathfarnham Strand in that year, and during which Musgrave received an injury from a ball which entered his abdomen and exited through his thigh. A second pair of cuttings dated 1864 treat of members of the Fitzgerald family who died by their own hands. The first of these, dated 2 May 1864 recounts the suicide of Sir Thomas Judkin Fitzgerald who drowned himself in the River Suir some days before 30 April 1864 when the article was posted by the Times correspondent in Dublin. This account gives circumstances of the suicide’s last letters and his behaviour immediately prior to his journey to the "Pig-hole" where he did the deed. In the second of this pair, dated for the same year, an account is given if the superstition surrounding descendants of “Flogger” Fitzgerald - so-named on account of his extreme cruelty towards captive United Irishmen in Tipperary in the sequel to the 1798 Rebellion. Mention is made of a son who drowned on the Nimrod and another descendant - his son - who hanged himself accidentally from a nail, apparently while showing his little sister and brother how his father had dealt with the rebels that he killed. By way of a main story, it also recounts the circumstances surrounding the burial of Sir Thomas whose death was apparently attributed to misadventure by the Coroner’s jury. Believing that it was suicide, a large crowd of persons variously called ‘peasants’ and ‘strangers’ attempted to prevent his burial in Ballygriffin churchyard with the result that the coffin was brought home and then returned with a guard of 150 constabulary to ensure his safe interment. A partially-legible marginal note refers the reader to [?Mofpey]’s History of England and to further article in the Times for 1 August 1863 giving ‘an account of this wretch’. The same hand appears to be responsible for some underlined words in the third report including the phrases ‘hereditary animosity to the family’ and ‘filled the grave with stones’, &c., (See copies - as attached.)

[ top ]

Criticism

James Kelly, Sir Richard Musgrave, 1746-1818 (Dublin: Four Courts Press 2009), 272pp.; also Kelly, ‘The Act of Union: its origin and background’, in Acts of Union: The Causes, Contexts and Consequences of the Act of Union, ed. Dáire Keogh & Kevin Whelan (Dublin: Four Courts Press 2001) - extract.

Note: The DNB entry on Musgrave was written by J. M. Rigg - viz., Dictionary of National Biography, ed. Sidney Lee, Vol. XXXIX (1894), pp.422–23.

[ top ]

Commentary

Patrick Kennedy calls Richard Musgrave ‘author of the least trustworthy history of the Insurrection of ’98 ever published, and recites a narrative about him from Sir Jonah Barrington. (Modern Irish Anecdotes [1872], p.68).

Cheryl Herr, For the Land They Loved (Syracuse UP 1991), makes much use of Memoirs of the Different Rebellions in Ireland (1801), noting its format with fold-out maps including ‘plan of the town of Arklow with part of the circumjacent country to illustrate the account of the attack of the rebels on that Town, June 9th 1798’.

Further: ‘The volume delineates some 40 battles that took place as part of the 1798 Rising, and it is these battles that Musgrave really means us to see as the “different rebellions’”. He spends 46 pages on early Irish history from the 5th c. to 1780, and 590 pages with 200 pages of appendix on the events of the latest Rebellion. The documentary style of his presentation allows him to introduce material that brings many of the conflicts to a kind of 3-dimensional life, however biased in political viewpoint.’ (Herr, op. cit., p.22f.).

Conor Cruise O’Brien, The Great Melody (1992), Richard Musgrave describes Burke simply as ‘the son of a popish solicitor in Dublin’; Cites Memoirs of the different rebellions in Ireland, from the arrival of the English; also a particular detail of that which broke out the 23rd of May 1798 ... with a concise history of the reformation in Ireland; and considerations for the means of extending its advantages therein (Dublin 1801), p.35 [. O’Brien, op. cit., p.12].

Further, Musgrave’s Memoirs note that an apprentice of Richard Burke noticed that a year after Edmund had gone to the Temple he ‘seemed much agitated in his mind and that they were alone, he frequently introduced religion as a topic of conversation’; he, the apprentice, believed that Burke was ‘become a convert to P---- ’; Burke’s father was ‘much concerned’ and had his brother-in-law Mr Bowen make ‘strict enquiry about the conversion of his son’, to the effect that Bowen reported he had been converted; ‘Mr Burke became furious, lamenting that the rising hope of his family was blasted, and that the expense he had been at in his education was now thrown away.’ Musgrave continued that ‘it was possible that Mr Burke, in the spring of his life [...] might have conformed to the exterior ceremonies of Popery, to obtain Miss Nugent, of whom he was very much enamoured; but it is not to be supposed, that a person of so vigorous and highly cultivated an understanding, would have continued under the shackles of that absurd superstition.’ Musgrave describes Burke’s father-in-law, Christopher Nugent, as ‘a most bigoted Romanist bred at Douay [Douai] in Flanders.’ (ibid.) [38]

Further: Sir Jonah Barrington wrote of Musgrave: ‘Sir Richard Musgrave who (except on the abstract topics of politics, religion, martial law, his wife, the Pope, the Pretender, the Jesuits, Napper Tandy and the whipping post) was generally in his sense[s], formed during those intervals a very entertaining addition to the company.’ (bibl. The Ireland of Sir Jonah Barrington, ed. H. Staples, London 1968), p.245; O’Brien, p.39).

Further: O’Brien later on quotes Musgrave as asserting that Burke’s younger brother Richard was in Ireland in 1765-66 on his [Edmund’s] behalf distributing money to Whiteboys (Memoirs, p.8; O’Brien, op. cit., p.[59].) O’Brien quotes Basil O’Connell who calls Musgrave ‘biased, vindictive, and inaccurate’ (Irish Genealogist (Vol. 3, No. I, 1956, p.21) but inclines to believe the assertion about Richard Burke’s whereabout - although Copeland tells him that it was physically impossible to be there; yet he considers Musgrave had a reason to believe so, ‘and this becomes therefore an essential part of the investigation.’ He further thinks that [‘]the evidence persuasive to Copeland was planted by Edmund to protect his brother.’ O’Brien considers the allegations of Burke’s fanning the flames of Whiteboyism extremely improbably on the basis of his class interests in common with the Nagles. [60].

Further: [Thomas] Hussey inappositely described by Richard Musgrave as ‘an infamous incendiary ... now living in the greatest intimacy with Messrs. Fox, Grey, and Sheridan.’ (Citing Dáire Keogh, ‘Thomas Hussey’, in Waterford History and Society, ed. [W. Nolan &] T. Power, Dublin 1992, p.574.)

[ top ]

| Nancy Curtin [Fordham University], ‘Not for Every Lady’s Nightstand’, review of Memoirs of the Irish Rebellion of 1798, ed. Steven W. Myers & Delores E. McKnight [rep.], in Irish Literary Supplement 15:1 (Boston March 1996) [Note: page-nums. in bracket are those in the edition.]: |

|

| Excerpt: |

|

|

|

|

| —Available online - copied 1996; re-accessed 31.08.2023; here re-paragraphed for webpage.] |

[ top ]

Kevin Whelan, The Tree of Liberty: Radicalism, Catholicism, and the construction of Irish Identity, 1760-1830 [Field Day] (Cork UP 1996), describes Musgrave’s memoir as ‘the matrix of memory’, portraying 1798 ‘as the result of a deep-seated popish plot ... It sought to establish parallels between 1641 and 1798, to depoliticise the 1790s, and to establish disreputable sectarian motives as the sole grounds of state, and especially to argue the case against Catholic Emancipation being part of the Union settlement’. (p.135; cited by Mary C. King, Hewitt Summer School, 1998 [as infra].)

Further [Kevin Whelan, op. cit., 1996], Musgrave’s material was ‘written down from oral examination of the deponents’, while informants were ‘personally paid by him for transport and accommodation costs in Dublin (allegedly from fears of swearing affadavits in their own counties).’ (Whelan, p.136; King, op. cit.). See also Kevin Whelan, ‘Origins of the Orange Order’, in Bullán: An Irish Studies Journal, 2, 2 (Spring/Summer 1996), p.28, noting his role in the encouragement of the Orange Order.

Mary C. King, conference paper on J. M. Synge’s fragmentary play of 1798 delivered to the Hewitt Summer School in 1998, regards that Synge’s play, with its final rejoinder - ‘go home and burn your history book ... it’s you were right and the book was wrong’ - as Synge’s ‘creative riposte to and critique of Musgrave’s technique in Rebellions, particularly in his intransigent conjuring up and naturalising of a binary,. Univocal, oppositional narrative which reduces the unity-in heterogeneity of 1798 to an essentialist account of “the great antipathy which ever existed between these sects” [...&c.].

James Kelly, ‘The Act of Union: its origin and background’, in Acts of Union: The Causes, Contexts and Consequences of the Act of Union, ed. Dáire Keogh & Kevin Whelan Dublin: Four Courts Press 2001): ‘Furthermore, many of the most important voices in conservatism - Sir Richard Musgrave and Patrick Duigenan most notably - were vigorous proponents of union. Their support was inevitably predicated on its being proposed upon “protestant principles”, which caused both the Irish executive and the British government serious problems. They believed that Catholic emancipation should follow the union, but they shrewdly ensured that this did not become a major public matter and it did not prevent the measure’s passing. Moreover, there is nothing to suggest that combined or separately the Rebellion [of 1798], the immediate prospect of the abolition of the Irish parliament[,] or the fear of further catholic empowerment prompted significant leaching from the ranks of Irish unionists.’ p.65.)

[ top ]

References

Dictionary of National Biography notes that he attached to the English connection but opposed to the Act of Union.

Library Catalogues

Belfast Central Public Library holds A Concise Account of the Events in the late Rebellion (1799); Memoirs of the Different Rebellions in Ireland [&c.] (1802). Belfast Linenhall Library also holds William Todd Jones, Authentic Details of an Affair of Honour between William Todd Jones and Sir Richard Musgrave; Reply from the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Ferns, Dr. James Caulfield.

[ top ]

1798: ‘The late rebellion, as well as all the former ones evince, that the lower class of the Irish do not consider it a crime to injure the person or property of a protestant fellow subject.” (Memoirs of the Different Rebellions in Ireland [...] (1801), p.150.United Irish: ‘This strongly marked the discriminating features of the conspiracy. Belfast was the centre of motion in the north, and its inhabitants, who were mostly presbyterians, meditated the establishment of a republick as their main object, and confidered assassination merely as the means of promoting it; but the mass of the conspirators in Munster, Leinster, and Connaught, being papists, aimed at the extirpation of protestants in the first instance, and as their primary object, of which the reader will be convinced in the sequel.’(Ibid., Ftn., p.150.)

How United?: ‘The only point in which the papists and the Presbyterians cordially united was, Revolution; but their views and expectations from it were widely different. The former considered it as the only means of recovering their ancient estates, and of acquiring a complete ascendancy; whereas, the establishment of a republican government was the chief object of the latter.’ (1995 Edn., p.161; cited by Nancy Curtin, review of Steven W. Myers & Delores E. McKnight, eds., Memoirs of the Irish Rebellion of 1798 (1995 Edn.; as supra.)

Sir Richard Musgrave, Memoirs of the Different Rebellions in Ireland [...] (1801), speaking in his Introductory Discourse of the ‘doctrine of exclusive salvation’ according to which the Catholic Church holds to the belief that only Catholics will be redeemed:

|

Catholics & dissenters: ‘[T]he great antipathy which ever existed between these sects [Catholicism and Presbyterianism]. I am much at a loss to know how they could ever be made to unite. I have been assured that the Presbyterians quitted the papists as soon as they discovered that they were impelled by the sanguinary spirit which was ever peculiar to their religion.’ (quoted in Whelan, op. cit., p.137; cited in King, supra).

Sir Richard Musgrave, Memoirs of the Different Rebellions in Ireland [...] (1801), writes: ‘Defenderifm was introduced into the county of Donegal from Connaught, by Leitrim and Rofcommon; and the doftrines of the united Irifhmen from Belfaft, in the year 1796, by men who appeared in the guife of pedlars.*’ - adding in a footnote his main thesis:

‘This strongly marked the discriminating features of the conspiracy. Belfast was the centre of motion in the north, and its inhabitants, who were moftly presbyterians, meditated the establishment of a republick as their main object, and confidered assassination merely as the means of promoting it; but the mass of the conspirators in Munster, Leinster, and Connaught, being papists, aimed at the extirpation of protestants in the sirft instance, and as their primary object, of which the reader will be convinced in the sequel.’ (p.132; note archaic “f”s for “s”s.) [Available at Internet Archive - online.]

The Irish Question: ‘Ireland in her present state may be considered as an intestine thorn in the side of England, as a strong outpost easily accessible to her enemies, who may at all times annoy her through it: instead of affording her strength, it will be an incessant source of weakness.’ (Memoirs of the Different Rebellions in Ireland, Enniscorthy [1995 Edn.], p.851; quoted in Kevin Whelan, ‘The Other Within: Ireland, Britain and the Act of Union’, in Dáire Keogh & Kevin Whelan, eds., Acts of Union: The Causes, Contexts and Consequences of the Act of Union, Dublin: Four Courts Press 2001, p.16.)

Whipping up: ‘The confpirators bound each other by oath to refift the laws of the land, and to obey none but thofe of captain Right; and fo ftrictly did they adhere to them, that the high fheriff of the county of Waterford,* could not procure a perfon to execute the fentence of the law on one of thefe mifcreants who was condemned to be whipped at Carrick-on-Suir, though he offered a large fum of money for that purpofe. He was therefore under the neceffity of performing that duty himfelf, in the face of an enraged mob.’ [Ftn. ‘*The writer of thefe pages [i.e., Musgrave] was high fheriff at that time.’ (Memoirs of the Different Rebellions in Ireland ... &c., 1801, p.46. [Note archaic “f”s for “s”s.]

| Links to the copies in the RICORSO Library as well as those at Internet Archive are available - as supra. |

[ top ]

Notes

Patrick Byrne, Dublin printer, issued pirated edns. of Musgrave’s works, viz., A Letter on the Present Situation (1795) and Considerations on the Present State of England and France (1796) [Cited in Richard Cargill Cole, Irish Booksellers and English Writers, 1740-1800, London: Mansell 1986, p.237.]

Poulett Scrope: Scrope an advocate of a Poor Law for Ireland in 1831, referred to Musgrave’s plan for the employment of the poor as satisfactory. (Cited p.75, Thomas G. Conway, ‘The Approach to an Irish Poor Law, 1828-33’, in Éire-Ireland, 6, 1, Spring 1971, pp.65-81.)

Sir William Musgrave (6th Bart., of Hayton Castle, Co. Cumberland), compiled England, Scotland, Ireland: Musgrave’s Obituaries Prior to 1800, parts 1 & 2 [properly A General Nomenclator and Obituary, with Referrence to the Books Where the Persons are Mentioned, and Where some Account of their Character is to be Found]. A CD ROM version is available from Family Tree Computing [online].

Thomas Richard Bentley: Bentley, who was author of Considerations on the State of Public Affairs ... 1799 (1799), was also an object of scorn in Richard Musgrave’s Memoirs of Different Irish Rebellions [...] (1801), where he calls it a ‘Jacobin pamphlet [which] abounds in falsehoods and mistatements’, identifying the unnamed author with other Englishmen who briefly visit Ireland and assimilate ‘the colour of whatever body he approaches’ like the ‘cameleon’. (Memoirs, Introduction, 1801, p.vi, n.).

[ top ]