| ‘Many a man has spent a hundred years trying to get the dimensions of it and when he understands it at last and enters the certain pattern of it in his head, by the hokey he takes to his bed and dies.’ (The Third Policeman, 1993 Edn., p.47; quoted by Joanne Moore, UG Essay, UUC 2003.) | |

| ‘That is a great curiosity, a very difficult piece of puzzledom, a snorter ...’ (Sargeant Pluck, in The Third Policeman; quoted my Michael Foley, in article on The Third Policeman, The Irish Times [Wed.] 26 Aug. 2015 - available online.) |

| Main Works | |

|

At Swim-Two-Birds The Poor Mouth [An Beal Bocht] The Third Policeman |

‘Keats and Chapman’ Best of Myles “Binchy and Bergin and Best” |

| Longer Extracts | |

| At Swim-Two-Birds (1939) |

The Third Policeman (1967) [also full-text 456KB copy - as attached] |

| Beginnings ... |

|

| —Quoted in Brendan Glacken, ‘Myles, the Da and the Brothers’, review of Ciaran Ó Nuallain, trans., The Early Years of Brian O’Nolan / Flann O’Brien / Myles na gCopaleen, in Irish Times (30 Jan. 1999), [q.p.]. |

At Swim-Two-Birds (1939)

|

[OPENING:] ‘Having placed in my mouth sufficient bread for three minutes’ chewing, I withdrew my powers of sensual perception and retired into the privacy of my mind, my eyes and face assuming a vacant and preoccupied expression. I reflected on the subject of my spare-time literary activities. One beginning and one ending for a book was a thing I did not agree with. A good book may have three openings entirely dissimilar and inter-related only in the prescience of the author, or for that matter one hundred times as many endings.’ (1967 Penguin edn. p.9). The Third Opening: Finn MacCool was a legendary hero of old Ireland. Though not mentally robust, he was a man of superb physique and development. Each of his thighs was as thick as a horse’s belly, narrowing to a calf as thick as the belly of a foal. Three fifties of fosterlings could engage with handball against the wideness of his backside, which was wide enough to halt the march of warriors through a mountain pass. (p.9; &c.) ‘The Pooka Fergus MacPhellimey, a species of human Irish devil endowed with magical power. John Furriskey, A depraved character, whose task is to attack women and behave at all times in an indecent manner. By magic he is instructed by Trellis to go one night to Donnybrook where he will by arrangement meet and betray PEGGY, a domestic servant. He meets her and is much surprised when she confides to him that Trellis has fallen asleep and that her virtue had already been assailed by an elderly man subsequently to be identified as Finn MacCool, a legendary character hired by Trellis on account of the former’s venerable appearance and experience, to act as the girl’s father and chastise her for her transgressions against the moral law, and that her virtue has also been assailed by Paul Shanahan, another man hired by Trellis for performing various small and unimportant parts in the story |

|

| [The poetry:] |

|

SHANAHAN, [reciting verses of Jem Casey]: When things go wrong and will not come right, / Though you do the best you can, / When life looks black as the hour of night / A PINT OF PLAIN IS YOUR ONLY MAN. (p.77; see longer extracts in RICORSO Library, “Irish Literary Classics”, infra.) |

|

[ top ]

Manuscript materials for At Swim-Two-Birds ultimately excised from the final typescript and published text:

|

| Good and evil (after Augustine) |

|

| [...] |

|

| Ringsend cowboys |

|

| Classical music |

|

|

| At Swim-Two-Birds (1939) | |

| Schematic Chart | Episodes & Motifs |

[ top ]

The Poor Mouth [An Beal Bocht] (Irish orig. 1941; trans. 1964): ‘In my youth we always had a bad smell in our house. Sometimes it was so bad that I asked my mother to send me to school, even though I could not walk correctly. Passers-by neither stopped nor even walked when in the vicinity of our house but raced past the door and never ceased until they were half a mile from the bad smell. There was another house two hundred yards down the road from us and one day when our smell was extremely bad the folks there cleared out, went to America and never returned. It was stated that they told people in that place that Ireland was a fine country but that the air was too strong there. Alas! there was never any air in our house.’ (p.22.) ‘Ambrose was an odd pig and I do not think that his like will be there again. Good luck to him if he be alive in another world today!’ (Ibid., p.28.)

The Poor Mouth [An Beal Bocht] (Irish orig. 1941; trans. 1964) - The President’s speech: ‘ - Gaels! he said, it delights my Gaelic heart to be here today speaking Gaelic with you at this Gaelic feis in the centre of the Gaeltacht. May I state that I am a Gael. I’m Gaelic from the crown of my head to the soles of my feet - Gaelic front and back, above and below. Likewise, you are all truly Gaelic. We are all Gaelic Gaels of Gaelic lineage. He who is Gaelic, will be Gaelic evermore. I myself have spoken not a word except Gaelic since the day I was born - just like you - and every sentence I’ve ever uttered has been on the subject of Gaelic. If we’re truly Gaelic, we must constantly discuss the question of the Gaelic revival and the question of Gaelicism. There is no use in having Gaelic, if we converse in it on non-Gaelic topics. He who speaks Gaelic but fails to discuss the language question is not truly Gaelic in his heart; such conduct is of no benefit to Gaelicism because he only jeers at Gaelic and reviles the Gaels. There is nothing in this life so nice and so Gaelic as truly true Gaelic Gaels who speak in true Gaelic Gaelic about the truly Gaelic language. I hereby declare this feis to be Gaelically open! Up the Gaels! Long live the Gaelic tongue! / When this noble Gael sat down on his Gaelic backside, a great tumult and hand-clapping arose throughout the assembly.’ (Ibid., 54-55; quoted in Brendan Kennelly, ‘Satire in Flann O’Brien’s The Poor Mouth’, in Journey into Joy: Selected Prose, ed. Åke Persson, Newcastle-upon-Tyne 1996, p.182-85; also in Joseph Brooker, Flann O’Brien, Tavistock: Northcote House 2005, p.63, cited in Geraldine Cameron, PG Dip., UUC 2011.)

The Poor Mouth (1964) [Bonapart’s hangover:] If the bare truth be told, I did not prosper very well. My senses went astray, evidently. Misadventure fell on my misfortune, a further misadventure fell on that misadventure and before long the misadventures were falling thickly on the first misfortune and on myself. Then a shower of misfortunes fell on the misadventures, heavy misadventures fell on the misfortunes after that and finally one great brown misadventure came upon everything, quenching the light and stopping the course of life. I did not feel anything for a long while; I did not see anything, neither did I hear a sound. Unknown to me, the earth was revolving on its course through the firmament. It was a week before I felt that a stir of life was still within me and a fortnight before I was completely certain that I was alive. A half-year went by before I had recovered fully from the ill-health which that night’s business had bestowed on me, God give us all grace! I did not notice the second day of the feis. (60-61; Kennelly, op. cit., 1996, p.185.)

The Poor Mouth (1964): ‘There was a man in this townland at one time and he was named Sitric O’Sanassa. He had the best hunting, a generous heart and every other good quality which earn praise and respect at all tirnes, But alas! there was another report abroad concerning him which was neither good nor fortunate. He possessed the very best poverty, hunger and distress also. He was generous and open-handed and he never possessed the smallest object which he did not share with the neighbours; nevertheless, I can never remember him during my time possessing the least thing, even the quantity of little potatoes needful to keep body and soul joined together. In Corkadoragha, where every human being was sunk in poverty, we always regarded him as a recipient of alms and compassion. The gentlemen from Dublin who came in motors to inspect the paupers praised him for his Gaelic poverty and stated that they never saw anyone who appeared so truly Gaelic. One of the gentlemen broke a little bottle of water which Sitric had, because, said he, it spoiled the effect. There was no one in Ireland comparable to O’Sanassa in the excellence of his poverty; the amount of famine which was delineated in his person. He had neither pig nor cup nor any household goods. In the depths of winter I often saw him on the hillside fighting and competing with a stray dog, both contending for a narrow hard bone and the same snorting and angry barking issuing from them both. He had no cabin either, nor any acquaintance with shelter or kitchen heat. He had excavated a hole with his two hands in the middle of the countryside and over its mouth he had placed old sacks and branches of trees as well as any useful object that might provide shelter against the water which came down on the countryside every night. Strangers passing by thought that he was a badger in the earth when they perceived the heavy breathing which came from the recesses of the hole as well as the wild appearance of the habitation in general.’ (88-89; Kennelly, op. cit., 1996., pp.186-87.) [See remarks in Kennelly, ‘Satire in Flann O’Brien’s The Poor Mouth’, in Journey into Joy: Selected Prose, ed. Åke Persson, Newcastle-upon-Tyne 1996, in Commentary, supra; see also the Irish original in Do. [full-text copy], in RICORSO Library, “Critical Classics”, infra.]

The Poor Mouth (1964): ‘For five hours I became a child of the ashes - a raw youngster rising up according to the old Gaelic tradition […] the foul stench of the fireplace stayed with me for a week; it was a stale, putrid smell and I do not think the like will ever be again.’ (q.p.) ‘Not only one fine oration followed this one but eight. Many Gaels collapsed from hunger and from the strain of listening while one fellow died most gaelically in the midst of the assembly.’ (q.p.) Also: ‘[…] I was almost twenty years old and one of the laziest and most indolent person living in Ireland. I had no experience of work and neither had I found any desire for it ever since the day I was born.’ (London: Flamingo Modern Classics, 1993), p.62. Further: ‘Yes! we had a great day of oratory at Corkadoraga that day!’ [q.p.]

[ top ]

The Third Policeman (Penguin 1986 Edn.) -

1st epigraph: ‘Human existence being a hallucination containing in itself the secondary hallucinations of day and night (the latter an insanitary condition of the atmosphere due to accretions of black air) it ill becomes any man of sense to be concerned at the illusory approach of the supreme hallucination known as death.’

Opening: ‘Not everybody knows how I killed Old Mathers, smashing his jaw in with my spade [... ] I was born a long time ago. My father was a strong farmer and my mother owned a public house. We all lived in the public house but it was not a strong house at all and was closed most of the day because my father was out at work on the farm and my mother was always in the kitchen and for some reason the customers never came until it was nearly bed-time; and well after it at Christmas-time and on other unusual days like that. I never saw my mother outside the kitchen in my life and never saw a customer during the day and even at night I never saw more than two or three together. But then I was in bed part of the time and it is possible that things happened differently with my mother and with the customers late at night. My father I do not remember well but he was a strong man and did not talk much except on Saturdays when he would mention Parnell with the customers and say that Ireland was a queer country. My mother I can recall perfectly. Her face was always red and sore-looking from bending at the fire; she spent her life making tea to pass the time and singing snatches of old songs to pass the meantime. I knew her well but my father and I were strangers and did not converse much; often indeed when I would be studying in the kitchen at night I could hear him through the thin door to the shop talking there from his seat under the oil-lamp for hours on end to Mick the sheepdog. Always it was only the drone of his voice I heard, never the separate bits of words. He was a man who understood all dogs thoroughly and treated them like human beings. My mother owned a cat but it was a foreign outdoor animal and, was rarely seen and my mother never took any notice of it. We were happy enough in a queer separate way.’ [For longer extracts, see RICORSO Library, “Irish Classics > Flann O’Brien”, via index, or direct.]

Planning the murder: ‘I do not know exactly how or when it became clear to me that Divney [...] intended to rob Mathers, and I cannot recollect how long it took me to realize he meant to kill him as well in order to avoid the possibility of being identified as the robber afterwards. I only knew that within six months I had come to accept this grim plan as a commonplace of our conversation.’ (Quoted in Roger Boylan, ‘“We Laughed, We Cried”: Flann O’Brien’s triumph, in Boston Review, 1 July 2008 - available online; accessed 05.08.2021.)

| The Third Policeman- de Selby Footnotes: |

|

| All quoted in Flore Coulouma, ‘Making sense of N/nonsense in Flann O’Brien’s At Swim-Two-Birds and The Third Policeman, a Wittgensteinian perspective’, in Corela: Cognition, representation, logic, HS, 12, 2012 - available online; accessed in OpenEditions - 22.07.2021) |

[ top ]

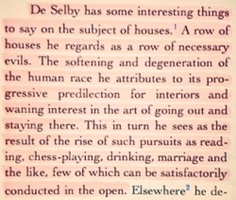

‘’Third Policeman - Opening of Chapter Two (on houses):

|

||||||

| —Posted on Facebook (22.03.2017). | ||||||

| Flann on The Third Policeman |

|

|

Life according to Joe ... |

||

|

| Omnium |

“I will tell you the size of it,” he said, “and indicate roughly the shape of it. It is no harm if you know unusual things because you will be a dead man in two days and you will be held incognito and in communicate in the meantime. Did you ever hear tell of omnium?” |

| Cf. shorter extract from same: |

Further—

|

| —Quoted in Joseph Brooker, ‘Do Bicycles Dream of Atomic Sheep? Forms of the Fantastic in Flann O’Brien and Philip K. Dick,’ in The Parish Review: Journal of Flann O’Brien Studies, 4, 2 (Spring 2020), pp.1-23 [available online - accessed 27.07.2021]. |

| See numerous further quotations from The Third Policeman - as attached. |

[ top ]

The Hard Life (1961): ‘It is not that I half knew my mother. I knew half of her: the lower half ‒ her lap, legs, feet, her hands and wrists as she bent forward. Very dimly I seem to remember her voice. At the time, of course, I was very young. Then one day she did not seem to be there any more. So far as I knew she had gone away without a word, no good-bye or good night. A while afterwards I asked my brother, five years my senior, where the mammy was (London: Souvenir Press 2011, p.11; quoted in Germán Asensio, ‘Flann O’Brien’s creative loophole’, in Estudios Irlandeses, March 2015, pp.1-13 - available online; accessed 22.07.2021.)

The Dalkey Archive (1965) [a description]: ‘The story concerns “a lowly civil servant”, Mick Shaughnessy, whose mundane life is sparked into fanciful and heroic possibilities by three people - a scientist named De Selby, James Joyce and Mick’s girl friend Mary. De Selby has not only discovered how to suspend time, but is so disgusted with history as to have devised a chemical compound which will remove oxygen from the atmosphere and thus destroy the world. James Joyce, he hears, is not dead but hiding in a pub in Skerries, a village near Dublin. Mick thinks he can prevent De Selby’s plan by introducing him to Joyce, “and inducing both to devote their considerable brains in consultation to some recondite, involuted and incomprehensible literary project, ending in publication of a book which would be commonly ignored and thus be no menace to universal sanity.” (Dalkey Archive, p.129; see by Timothy McLaughlin, ‘Brian O’Nolan / Flann O’Brien / Myles: Playing / Spoiling’, in Cycnos, 10, 2 [spec. issue: “À quoi jouent les Irlandais?”] (Juin 1993), available online - accessed 15.10.2011.)

Myles Na Gopaleen, ‘Cruiskeen Lawn’, in The Irish Times (11 April 1959) - rep. in The Irish Times (22 Oct. 2011). I have pondered a bit further the remarks I made the other day about the Presidency: I said I did not consider Mr de Valera eligible at all because he was born in the USA but if he is allowed to compete, then we seem to have, subject only to the minimum age condition, a possible selection of Presidents from an enormous bloc of the total population of the earth. Just as in the case of a lord mayor, the title of President implies no sex restriction.

First, what IS a President? The word used in the Constitution is uachtarán. There is no such word in true Irish and it is the improvisation of some yahoo. Among similar connotations suggesting top, uachtar means cream, and I would say uachtarán, if it makes sense at all, means ice cream merchant. Very dignified, or glanghaoidhilg an ghur-aire! The correct Irish is Presidens (see, e.g., p.67, Ó Lochlainn’s Tobar Fiorghlan, letter from O’Hussey, 1605).

That word is, of course, from the L. Praesideo, praesidens, a president, director, ruler, i.e. “I sit before or in front of.”

Well then, whom should we pick from our profusion of material? The other day I suggested the Dalai Lama but I believe he is too young. In our own country we have many people of the first distinction, such as Joe McGrath, Ernest Blythe, Oliver Flanagan, Lord Brookeborough and the Lady Fitzwilliam but, somehow, I think they would courteously decline the honour, having perhaps other preoccupations.

In any case, on the principle that the director of a large hospital should never be a doctor, I feel we would be well advised to look outside the walls.

What qualifications do we seek? I would specify modest essentials such as good and powerful personality, commanding appearance, accomplished speaker, experience of the world, and the quality of not being afraid on occasion to be a sloven or be so silly as to think that magnum is just an old Latin gender. Nothing very exclusive about that kriterion. Let yourself in, nearly.

Let me suggest a few myself, with brief reasons.Groucho Marx - Yeats wrote of a lady who had “the walk of a queen,” and while Groucho’s walk is scarcely that of a king, it is some walk. It would look marvellous at a reception in Iveagh House. He can talk, too, and smoke cigars. He might even talk Irish.

Harry Truman - Can talk well, too, has the experience and is a skilled desk-bombardier should war come.

Paul Robeson [sic. for Robson] - Can sing and act, well in with Kruschev and has been persecuted by the Americans. Excellent neutral type. Drinks.

Randolph Churchill - Has the authentic magistral manner, sound bottle-man, raconteur and ... hates the Irish.

Marilyn Monroe - Hmm. Doubtful. Cute, mind you, but she’d have to bring that Miller with her - sombre type, thoughtful, smokes pipes, writes. Just what would he be? Presidential Consort? I’m afraid the arrangement would snarl up protocol and worry the fancy-pants in Iveagh H.Well, reader, why not get out your own list and send it on to me. What was that? MYSELF? Aw now look here, have I not enough on my hands at my estates in Santry? Yes, I suppose I could go on living there - “at or near Dublin,” the book says; but I couldn’t have tramps in black tailcoats coming out with those female baboons they call their wives to drink my whiskey, or political bowsies riding out to ask me for their seals. Faith and I would give them seals! Besides, I would have Brendan Behan moving in to live with me.

A horrible thought occurs to me. Article 12 (8) of the Constitution prescribes that the President, on entering office, shall take a solemn (and I think blasphemous) oath about upholding the Constitution and the laws. If elected, I might agree to recite the words, but first warning those present that I regarded the oath as an empty formula and not binding on me in conscience. Has been done before, a man told me.The Irish Times - online; accessed 22.11.2011.

Myles na nGopaleen on the Irish People suited to De Valera’sRepublic (à la his St Patrick’s Day Speech): We are extremely nice people. A humble community of persons drawn together in our daily round of uncomplicated agricultural tasks by the strongest traditional ties ... Our conversation - gay, warm and essentially clean - is confined to the charming harmless occurrences of every-day life [...] The wild and morbid degeneracy of the outer world does not concern us .... A wide and benevolent administration protects us from backin’ alien horses, I beg your pardon, bacchanalian courses [...] What is called ‘news’ (by which one means the perverted sensationalism of the yellow press) does not concern us. We are not amused. Rumour (that recumbent jewel or lying jade) once had it that a war was going to break out. Nothing ever came of it, of course. “Cruiskeen Lawn”, 15 Feb. 1943, p.3.)

—Quoted in Germán Asencio Peral, ‘“One does not take sides in these neutral latitudes”: Myles na gCopaleen and The Emergency’ [Universidad de Almería], in IJES: International Journal of English Studies Univ. of Murcia [06/10/2017 - online; accessed 20.07.2021; see also Peral’s commentary - supra.)

Myles Na Gopaleen, ‘Cruiskeen Lawn’, in The Irish Times (4 Dec. 1944) - rep. in The Irish Times (3 Oct. 2011). Many years ago a Dublin friend asked me to spend an evening with him. Assuming that the man was interested in philosophy and knew that immutable truth can sometimes be acquired through the kinesis of disputation, I consented. How wrong I was may be judged from the fact that my friend arrived at the rendezvous in a taxi and whisked me away to a licensed premises in the vicinity of Lucan.

Here I was induced to consume a large measure of intoxicating whiskey.

My friend would not hear of another drink in the same place, drawing my attention by nudges to a very sinister-looking character who was drinking stout in the shadows some distance from us.

He was a tall cadaverous person, dressed wholly in black, with a face of deathly grey. We left and drove many miles to the village of Stepaside, where a further drink was ordered. Scarcely to the lip had it been applied when both us noticed - with what feelings I dare not describe - the same tall creature in black, residing in a distant shadow and apparently drinking the same glass of stout.

We finished our own drinks quickly and left at once, taking in this case the Enniskerry road and entering a hostelry in the purlieus of that village.

Here more drinks were ordered but had hardly appeared on the counter when, to the horror of myself and friend, the sinister stranger was discerned some distance away, still patiently dealing with his stout.

We swallowed our drinks raw and hurried out. My friend was now thoroughly scared, and could not be dissuaded from making for the far-away hamlet Celbridge; his idea was that, while another drink was absolutely essential, it was equally essential to put many miles as possible between ourselves and the sinister presence we had just left.

Need I say what happened? We noticed with relief that the public house we entered in Celbridge was deserted, but as our eyes became more accustomed to the poor light, we saw him again; he was standing in the gloom, a more terrible apparition than ever before, ever more menacing with each meeting. My friend had purchased a bottle of whiskey and was now dealing with the stuff in large gulps.

I saw at once that a crisis had been reached and that desperate action was called for.

“No matter where we go,” I said, “this being will be there unless we can now assert a superior will and confound evil machinations that are on foot. I do not know whence comes this apparition, but certainly of this world it is not. It is my intention to challenge him.”

My friend gazed at me in horror, made some gesture of remonstrance, but apparently could not speak.

My own mind was made up. It was me or this diabolical adversary: there could be no evading the clash of wills, only one of us could survive. I finished my drink with an assurance I was far from feeling and marched straight up to the presence.

A nearer sight of him almost stopped the action of my heart; here undoubtedly was no man but some spectral emanation from the tomb, the undead come on some task of inhuman vengeance.

“I do not like the look of you,” I said, somewhat lamely.

“I don’t think so much of you either,” the thing replied; the voice was cracked, low and terrible.

“I demand to know,” I said sternly, “why you persist in following myself and my friend everywhere we go.”

“I cannot go home until you first go home,” the thing replied. There was an ominous undertone in this that almost paralysed me.

“Why not?” I managed to say.

“Because I am the taxi-driver!”

Out of such strange incidents is woven the pattern of what I am pleased to call my life.The Irish Times - online; accessed 3.10.2011 ‘Keats and Chapman once climbed Vesuvius and stood looking down into the volcano, watching the bubbling lava and considering the sterile ebullience of the stony entrails of the earth. Chapman shuddered as if with cold or fear. / “will you have a drop of the crater?” Keats said.’ (Best of Myles, ed. Kevin O’Nolan, Grafton 1987; Paladin Edn., p.183.) Other punning punch-lines are: ‘ere the bloom of that valet shall fade from my heart’; ‘Dogging a fled horse’; ‘great mines stink alike’; ‘Schubert […] a lieder-writer’ ) ‘His B.Arch is worse than his bite’; ‘A terrible man for his bier’; ‘It will clear the heir’; ‘Foals rush in where Engels feared to tread’; ‘brute and ranch’; ‘The last roes of summer’ (Ibid., pp.180-200.)

The Best of Myles, ed. Kevin O’Nolan (London: Grafton 1987 [Paladin Edn.]) - “Catechism of Cliché”: ‘[…] An interval is right. What we all want is a good long walk in the country, plenty of fresh air and good wholesome food. This murder of my beloved English language is getting in under my nails. There are, of course, other branches of charnel-house fun into which I have not yet had the courage to lead my readers. Not quite the clichés but things that smell the same and worse. Far worse. Things like this, I mean: / Of course, gin is a very depressing drink. / The air in Budoran is very bracing. / You’ll see the whole lot of us travelling by air before you’re much older. / Your man is an extraordinary genius. / Of course, the most depressing drink of the lot is gin.’ (p.207.)

The Best of Myles: ‘You know the limited edition ramp. If you write very obscure verse (and why shouldn’t you, pray?) for which there is little or no market, you pretend that there is an enormous demand, and that the stuff has to be rationed. Only 300 copies will be printed, you say, and then the type will be broken up for ever. Let the connoisseurs and bibliophiles savage each other for the honour and glory of snatching a copy. Positively no reprint. Reproduction in whole or in part forbidden. Three hundred copies of which this is Number 4,312. Hand-monkeyed oklamon paper, indigo boards in interpulped squirrel-toe, not to mention twelve point Campile Perpetua cast specially for the occasion. Complete, unabridged, and positively unexpurgated. Thirty-five bob a knock and a gory livid bleeding bargain at the price. / Well I have decided to carry this thing a bit farther. I beg to announce respectfully my coming volume of verse entitled “Scorn for Taurus”. We have decided to do it in eight point Caslon on turkey-shutter paper with covers in purple corduroy. But look out for the catch. When the type has been set up, it will be instantly destroyed and NO COPY WHATEVER WILL BE PRINTED. In no circumstances will the company’s servants be permitted to carry away even a rough printer’s proof . The edition will be so utterly limited that a thousand pounds will not buy even one copy. This is my idea of being exclusive. / The charge will be five shillings. Please do not make an exhibition of yourself by asking me what you get for your money. You get nothing you can see or feel, not even a receipt. But you do yourself the honour of participating in one of the most far-reaching experiments ever carried out in my literary work-shop. (p.228; quoted in Timothy Mcloughlin, ‘Brian O’Nolan / Flann O’Brien / Myles: Playing / Spoiling’, in Cycnos, 10 2 [“À quoi jouent les Irlandais?”] (Juin 1993), available online - accessed 15.10.2011.)

[ top ]

More Myles ...

| ‘Compartmentation of personality’ - letter from Keith Hopper to TLS (15 March 2009) | |

Sir, – |

|

| Keith Hopper Kellogg College, 62 Banbury Road, Oxford. |

|

[ top ]

“Binchy and Bergin and Best”: ‘My song is concernin’ / Three sons of great learnin’ / Binchy and Bergin and Best, / They worked out that riddle / Old Irish and Middle, / Binchy and Bergin and Best, / they studied far higher / Than ould Kuno Meyer / And fanned up the glimmer / Bequested by Zimmer / Binchy and Bergin and Best. // They rose in their nightshift / To write for the Zeitschrift, / Binchy and Bergin and Best, / They proved they were bosses / At wrastling with glosses, Binchy and Bergin and Best, / they made good recensions / Of ancient declensions, / And careful redactions / To their three satisfactions / Binchy and Bergin and Best. // The went for a dander / With Charlie Marstrander / Binchy and Bergin and Best. / They added their voices / (Though younger) to Zeuss’s, / Binchy and Bergin and Best. / Stout chase the three gave / Through the Táin for Queen Maeve / And played “Find the Lady” / With Standish O’Grady, / Binchy and Bergin and Best. // They sang in the coir / Of the Institute (Higher) / Binchy and Bergin and Best,[266] / And when they saw fit / The former two quit, / Binchy and Bergin and Best / But the third will remain / To try to regain / At whatever coset / Our paradigms lost, / Binchy and Bergin and Best. // So forte con brio / Three cheers for the trio, / Binchy and Bergin and Best, / These friends of Pokorni / Let’s toast in Grand Marnier, / Binchy and Bergin and Best - / These justly high-rated, / Advanced, educated, / And far from facetious / Three sons of Melesius, / Binchy and Bergin and Best.’ (The Best of Myles, London: Grafton 1987; Paladin edn. 1992, pp.266-67; also quoted in Pól Ó Dochartaigh, ‘The Source of Hell: Professor Julius Pokorny of Vienna in Ulysses’, in James Joyce Quarterly, 41, 2003-04, pp.825-29, citing Irish Times, 18 March 1942, p.2.) [See Daniel Binchy, Osbert Bergin, Richard Best elsewhere in Ricorso.]

[ top ]

Miscellaneous (Myles na Gopaleen, &c.)

| Myles on the Irish Nation (“Cruiskeen Lawn”) | ||

|

Irish brachycephalics Language Humbugs: ‘Literary Criticism’ (in “Cruiskeen Lawn”):

Eire (Incorporation) Act: ‘Dear M. Chairman - I write to tender with great regret my resignation from the Irish people. I am compelled to take this step for personal reasons and trust yourself and your co-directors to will see your way to accept it. Thanking you for past courtesies, M.’ (Ibid., 14 Dec. 1943; as an outcome of ensuing exchanges with the Board, M. finally agrees to remain a part-time Irishman.)

Glun na Buaidh: ‘I was recently held up again at a Dublin street corner by a small crowd who were listening to a young man with a strong North of Ireland accent who was aloft on a little Irish scaffold. / “Glun na Buaidhe,” he roared, “has its own ideas about the banks, has its own ideas about dancing. There is one sort of dancing that Glun na Buaidhe will not permit and that is jazz dancing. Because jazz dancing is the product of the dirty nigger culture of America, the dirty low nigger culture of America.” / Substitute jew for nigger and you have something beautiful and modern. But what pained me was the fact that nobody present laughed. There is something comic about revivalists who have no idea of what they are trying to revive. What a shock this young man would get if he could read what remains to us of the literature of our tough and bawdy ancestors.’ ([Idem.?].)

Population: ‘The whole country lacks the density of population that would sustain even the fraction of “planning” that is proper to the temperament and economy of this country [...] To plan so elaboratley the material surroundings of the few folk one sees around doesn’t make much sense. As well erect traffic lights in a grave-yard.’ (Ibid., 10 May, 1944.)

The Irish Language: ‘A lady lecturing on the Irish language drew attention to the fact (I mentioned it myself as long ago as 1925) that while the average English speaker gets along with a mere 400 words, the Irish-speaking peasant uses 4,000. Considering what most English speakers can achieve with their tiny fund of noises, it is a nice speculation to what extremity one would be reduced if one were locked up for a day with an Irish-speaking bore and bereft of all means of committing murder or suicide. My point, however, is this. The 400/4,000 ratio is fallacious; 400/400,000 would be more like it.’ (From The Best of Myles, Dalkey Archive Press Edn. 1999, pp.278-79; quoted by Geraldine Cameron, PG Dip. UU 2011.)

United Nations membership: ‘As if to keep pace with such disreputable domestic conduct, it was casually announced last week that Ireland had been elected to the United Nations Organisation. It was a “package deal,” to repeat a phrase courtesy of the U.S.S.R. This country was put into the same box as Cambodia, Rumania, Libya, Jordan, Italy, Hungary, Finland, Ceylon, Austria and Spain. Ireland has now become a fully-fledged nation, just like Libya or Jordan. We are home at last.’ (“Cruiskeen Lawn”, 21 Dec. 1955; quoted in Germán Asensio Peral, “Myles na gCopaleen’s Cruiskeen Lawn (1940-66) and Irish Politics” [Phd. Thesis] Universidad de Almería 2020, p.81 [available as .pdf online; accessed 22.07.2021].) |

[ top ]

[ top ]

Letters to Ethel Mannin (responding to her change of ‘wilful obscurity’ when he sent At Swim-Two-Birds to her]: ‘It [At Swim-Two-Birds] is a belly-laugh or high-class literary pretentious slush depending on how you look at it. Some people say it is harder on the head than the worst whiskey, so do not hesitate to burn the book if you think that’s the right thing to do.’ (12 July 1939). Further: ‘It is a pity you do not like my beautiful book, as a genius I do not expect to be readily understood but you may be surprised to know that my book is a definite milestone in literature, completely revolutionises the English novel and puts the shallow pedestrian English writers in their place. Of course I know you are prejudiced against me on account of the IRA bombings […] to be serious I can’t understand your attitude to stuff like this. It is not a pale-faced sincere attempt to hold the mirror up and had nothing in the world to do with James Joyce. It is supposed to be a lot of belching, thumb-nosing and belly-laughing and I honestly believe that it is funny in parts. It is also by way of being a sneer at all the slush which has been unloaded from this country on the credulous English although they, it is true, manufacture enough of their own odious slush to make the import unnecessary. I don’t think your dictum about making the meaning clear would be upheld in any court of law. You'll look a long time for clear meaning in The Marx Brothers or Karl Marx for that matter.’ (14 July 1939) [The foregoing both quoted [in part] in Cronin, No Laughing Matter, 1989, p.104; see also Sue Asbee, Flann O’Brien, Boston: Twayne Publ. 1991, p.10).

Letter to Messrs. Longmans: ‘Briefly, the story I have in mind [for The Third Policeman] opens as a very orthodox murder mystery in a rural district. The perplexed parties have recourse to the local barrack which, however, contains some very extraordinary policemen who do not confine their investigations or activities to this world or to any known planes or dimensions. Their most casual remarks create a thousand other mysteries but there will be no question of the difficulty or “fireworks” of the last book. The whole point of my plan will be the perfectly logical and matter-of-fact treatment of the most brain-staggering imponderables of the policemen. I should like to do this rather carefully and spend some time on it […].’ (1 May 1939; quoted [with the above] in Cronin, No Laughing Matter, 1989 pp.110-11; but note some variation from version printed on the back cover of the Calder Edn. of Third Policeman.)

Letter to William Saroyan: ‘I guess it [At Swim-Two-Birds] is a bum book anyhow. I am writing a very funny book now about bicycles and policemen and I think it will be perhaps good and early a little money quietly.’ (25 Sept. 1939; see Notes, infra.) Further: ‘The only good thing about it is the plot and I have been wondering whether I could make a crazy Saroyan play out of it. When you get to the end of this book you realise my hero or main character (he’s a heel and a killer) has been dead throughout the book and that all the queer ghastly things which have been happening to him are happening in a sort of hell which he has earned for the killing Towards the end of the book (before you know he’s dead) he manages to get back to his own house where he used to live with another man who helped in the original murder. Although he has been away three days, this other fellow is 20 years older and dies of fright when he sees the other lad standing in the door. Then the two of them walk back along the road to the hell place and start going through the same terrible adventures again, the first fellow being surprised and frightened at everything just as he was the first time and as if he had never been through it before. It is made clear that this sort of thing goes on forever - and there you are. It is supposed to be very funny but I don’t know about that either […] . I envy you the way you write […] I can never seen to get anything just right […] Nevertheless, I think the idea of a man being dead all the time is pretty new. When you are writing about the world of the dead - and the damned - where none of the rules and laws (not even the Law of Gravity) holds good, there is any amount of scope for back chat and funny cracks [var. stories].’ (14 Feb. 1940; quoted in Cronin, No Laughing Matter, 1989, p.99.)

Note: Martin Esslin quotes O’Brien’s letter to Saroyan [‘I think the idea of a human being dead is pretty new ... backchat and funny cracks’] with this comment: ‘one is confronted with the madness of the human condition, is enabled to see his situation in all its grimness and despair [...] By seeing his anxieties formulated he can liberate himself from them.’ (Esslin, The Theatre of the Absurd, 1980, p.146.)

[ top ]

James Joyce (I): ‘Humour, the handmaid of sorrow and fear, creeps out endlessly in all Joyce’s works. He uses the thing, in the same way as Shakespeare does but less formally, to attenuate the fear of those who have belief and who genuinely think that they will be in hell or in heaven shortly, and possibly very shortly. With laughs he palliates the sense of doom that is the heritage of the Irish Catholic. True humour needs this background urgency, Rabelais is funny, but his stuff cloys. His stuff lacks tragedy.’ [‘Bash in the Tunnel’, in Envoy, April 1951, p.11.]

James Joyce (II): ‘[Joyce was] illiterate’; his ‘every foreign language quotation was incorrect’; his few sallies at Greek at wrong, and his few attempts at a Gaelic phrase absolutely monstrous.’ (‘Cruiskeen Lawn’, The Irish Times, 16 June [Bloomsday], 1954; quoted in Cronin, No Laughing Matter, 1989, p.111.)

James Joyce (III): in conversation with Samuel Beckett, O’Brien called Joyce ‘that refurbisher of skivvies stories’. (Quoted in Cronin, No Laughing Matter, 1989, p.158 - remarking that Beckett was shocked at what he heard.)

James Joyce (IV): ‘N í IRISH LITERATURE a bhfuil scríobhtha ag James Joyce adeir-sé, acht [267] tá an teideal sin ion luaidhte aige i dtaobh SÉADHNA leis an Athair Ó Laoghaire. Ní bhainfidh an té a léigh an da leabhar tathneamh as an ráiteas sin. Gan bacadh lis an focal IRISH is litríocht den chéad aicme ULYSSES again ní litríocht ar chor ar bith, olc nó maith, aon line a scríobh an t-Athair Peadar. Is féider leat (ma ta an léigheann agat rud nach bhfuil) ULYSSES a léigheamh i Seapanais acht ní féidir SÉADHNA a léigheamh fiú i mBéarla. […] &c.]’ (The Best of Myles, London: Grafton 1987; Paladin edn. 1992, pp.267-68.)

James Joyce (V): Note that Joyce is the butt of a recurrent joke in The Dalkey Archive which represents him as still living and writing pamphlets for the Catholic Church while hiding out in an Irish rural village.

James Joyce (VI): ‘I do not accept that JAJ was demolished by failure of FW [Finnegans Wake] to resound in the BELL-fries of the world. He did expect that result. FW was a private leisure exercise, and intended only for coteries and US slobs. Nor was he dismayed by the reception of Ulysses, burning of copies at Folkstone docks etc. Ten years were to pass before the book got proper recognition and& JAJ, knowing what was in the book, knew he could afford to wait. By the early twenties he had got his hooks into that wealthy US lady and money trouble no longer bothered him. His main interest in life was acting the ballocks as grd. seigneuer [grand seigneur].’ (Letter to Niall Montgomery, quoted in Clair Wills, ‘Anti-Writer’, review of Maebh Long, ed., The Collected Letters of Flann O’Brien, in London Review of Books, 41, 7 (4 April 2019) - see copy in RICORSO Library > Criticism > Reviews - as attached.)

John Millington Synge: ‘But when the counterfeit bauble began to be admired outside Ireland by reason of its oddity and “charm”, it soon became part of the literary credo here that Synge was a poet and a wild celtic god, a bit of genius, indeed, like the brother. We, who knew the whole insideouts of it, preferred to accept the ignorant valuations of outsiders on things Irish. And now the curse has come upon us, because I have personally met in the streets of Ireland persons who are clearly out of Synge’s plays. They talk and dress like that, and damn the drink they’ll swally but the mug of porter in the long nights after Samhain.’ (Flann O’Brien, The Best of Myles, London: Flamingo 1993, p.235; quoted in Germán Asensio, ‘Flann O’Brien’s Creative Loophole’, in Estudios Irlandeses [Almería U., Spain] 5 March, 2015 - available online; accessed 2707.2021)

[ top ]

O’Connor & O’Faoláin: O’Brien and called Frank O’Connor ‘the Dean of the Celtic Faculty’ and criticised Seán O’Faolain for writing ‘stories about wee Annie going to her first confession, stuff about country funerals, old men in chimney nooks after fifty years in America, will-making, match-making - just one long blush for many an innocent man life me, who never harmed them.’. (See Cronin, No Laughing Matter, q.pp.; quoted by Keith Hopper, Oxon.; IASAIL conference 1999.)

Writing in English: ‘It’s fairly obvious I haven’t much to say today. Sow what? Sow wheat / Ah-ha, the old sow-faced cod, the funny man, clicking out his dreary blob of mirthless trash. The crude grub-glutted muck-shuffler slumped on his hack-chair, lolling his dead syrup eyes through other people’s books to lift some lousy joke. English today, have to be a bit careful, can’t get away with murder so easily in English. Observe the grey pudgy hand faltering upon the type-keys. That is clearly the hand of a man that puts the gut number one. Not much sacrifice there. Yes but he has a conscience, remember. He has a conscience. He does not feel too well today […] incapable of writing short bright well-constructed newspaper article, notwithstanding the fact editors only too anxious to print and pay for suitable articles, know man who took course Birmingham School of Journalism, now earns 12,000 pounds in his spare time. If you can write a letter you can write articles for newpapers. Editors waiting […] &c.]’ (The Best of Myles, London: Grafton 1987; Paladin edn. 1992, p.313.)

Irish Bardic Poetry: ‘The exhibition, which is the result of years of training by kindness and a carefully thought-out dietary system, comprises, among other achievements, the recitation of verse. Our greatest living phonetic expert (wild horses shall not drag it from us!) has left no stone unturned in his efforts to elucidate and compare the verse recited and has found it bears a striking resemblance (the italics are ours) to the ranns of ancient Celtic bards. We are not speaking so much of those delightful lovesongs with which the writer who conceals his identity under the graceful pseudonym of the Little Sweet Branch has familiarised the bookloving world but rather (as a contributor D.O.C. points out in an interesting communication published by an evening contemporary) of the harsher and more personal note which is found in the satirical effusions of the famous Raftery and of Donald MacConsidine to say nothing of a more modern lyrist at present very much in the public eye. We subjoin a specimen which has been rendered into English by an eminent scholar whose name for the moment we are not at liberty to disclose though we believe our readers will find the topical allusion rather more than an indication. The metrical system of the canine original, which recalls the intricate alliterative and isosyllabic rules of the Welsh englyn, is infinitely more complicated but we believe our readers will agree that the spirit has been well caught. Perhaps it should be added that the effect is greatly increased if Owen’s verse be spoken somewhat slowly and indistinctly in a tone suggestive of suppressed rancour.’ [q. source.]

Language revival (1): ‘Will old Ireland survive? Not unless we work. We will survice if we deserve survival. Our destiny is in our own hands. Quisque est faber fortunae suae. We must pull together, sink our differences and behave with dignity and decorum. And above all, work. Work for Ireland. How queer that sounds. Not die, mind you. Work. Work for the old land. And at evening time, when reclinging at our frugal fireside, saturated by the noble tiredness that is conferred by honest toil, in the left hand let there be no alien printed trash but the first book of O’Growney. There, the, is an ideal for you, something you can do for Ireland. “I will let no evening pass without an hour at O’Growney.” The old tongue. The old tongue that was spoken by our forefathers. Learning Irish and all working together - for Ireland. Let us do that and we will surely survive. Erin go bragh! Unfurl the old flag, three crowns on a blue field, the old flag of Erin. Our hears are sound and our arms are strong. And what is our watchword? “Work”. Let our watchword henceforth be that small word with four letters: w-o-r-k. WORK! / Next speech, next speech, please. Clapping. Senile old chairman.’ (The Best of Myles, London: Grafton 1987; Paladin edn. 1992, p.309.) Cf., O’Brien’s facetious recitation of the nationalist cliché: ‘What is the sole and true badge of nationhood?’ - ‘The national language’. ‘With what also would it be idle to seek to revive the national language’ - ‘Our distinctive national culture’.

Language revival (2): O’Brien saw no prospect of reviving Irish ‘at the present rate of going and way of working’, but agreed with O’Casey that it was ‘essential, particularly for any sort of literary worker.’ Further: ‘It supplies that unknown quantity in us that enable[s] us to transform the English language and this seems to hold for people who have little or no Irish, like Joyce. It seems to be an inbred thing.’ (Letter to Sean O’Casey following praise for An Béal Bocht, 13 April, 1942; quoted in Cronin, No Laughing Matter, 1989, p.144).

English oddities: ‘I often wonder am I […] mad? Do I take that rather Irish thing, O’Fence, too easily? I go into a house, for instance. My “host” says “sit down”. Now why sit down? Why must be be so cautious and explicit. Is there not a clear suggestion there that if he had neglected to be precise, he might turn round to find me seated on top of the bookcase, the head bent to avoid the ceiling and the air thick with fractured cobwebs? How equally stupid the phrase “stand up!”. And how mysteriously the sit-down fight as opposed to the stand-up fight!’

[ top ]

No God and Two Patricks (on T. F. O’Rahilly and Erwin Schroedinger’s theories), ‘A friend has drawn my attention to Professor O’Rahilly’s recent address on ‘Palladius and Patrick’. I understand also that Professor Schroedinger has been proving lately that you cannot establish a first cause. The first fruit of the Institute therefore, has been an effort to show that there are two Saint Patricks and no God. The propagation of heresy and unbelief has nothing to do with polite learning, and unless we are careful this Institute of ours will make us the laughing stock of the world.’ (Cited in Allanah Hopkin, The Living Legend of St Patrick, NY: St. Martin’s Press, 1989, p.151; see further under DIAS, in Notes, infra; and see also bibliographical details under O’Rahilly, q.v.) Cf. St. Augustine’s remark in The Dalkey Archive: ‘Two Saint Patricks? We have four of the buggers in our place and they’d make you sick with their shamrocks and shenanigans and bullshit.‘ (q.p.)

Modernisation: ‘I solemnly warn Pat to look out for himself. Hospitals are being planned for him, clinics, health centres, stream-lined dispensaries. I can see the new Ireland all right, in mime-hind’s eye. The decaying population tucked carefully in white sterilised beds, numb from drugs, rousing themselves only to make their wills in Irish [...]. It is my considered view that Paud keeping step with world hysteria in the belief that he is being “modern” is a woeful spectacle, is nowise funny.’ (‘Cruiskeen Lawn’, 10 May, 1944; Cronin, No Laughing Matter, 1989, p.173).

Furrin publications: It seems to me that all national publications, of whatever country, gain in vitality by a process of interaction with imported papers. The same is true of Irish people’s blood. It is more and not less foreigners we want here and there is no limit to our requirements of foreign material for germination.’ (‘Cruiskeen Lawn’, 3 Jan. 1957; quoted in Anthony Cronin, No Laughing Matter: The Life and Times of Flann O’Brien, 1989, p.136).

Civil Service Pension Scheme: ‘The bulk of the material in Parliament at present is dangerously mediocre and the considerable problems of the future can be hopefully attacked only if the attitude to those forced to enter the administrative service is emancipatory rather than restrictive. People of intelligence whose parents have no money have virtually no other choice. Children of the well-to-do enter the professions and the majority are too absorbed in their lucrative work to make any contribution to public affairs. The only other considerable class is the business community. Business experience seems to [concern] an ex parte and unduly materialistic mentality; businessmen in public life have not been impressive. The administrator, on the other hand, has uniquely useful experience of the structure and function of the modern civil organism. It would be difficult to imagine a better deputy than a man who has served for 20 years as a County manager and who retired in his prime (say at 50) to take a hand in public affairs’. (“Heads of Civil Service Superannuation Bill”, Nat. Library of Ireland [NLI]; quoted in Cronin, op. cit., 1989, c.p.160.)

Importance of art?: ‘The main thing to remember is the unimportance of art. It is very much a minority activity’. (The Irish Times, q.d.; quoted in Sue Asbee, Flann O’Brien, Twayne, 1991, p.66.)

Christian Brothers: ‘I remember a loutish teacher […] I would not be bothered to denounce such people as sadists, brutes, psychotics, I would simply dub them criminals and would expect to see them jailed.’ (‘Cruiskeen Lawn’, 20 Dec. 1965; Cronin, No Laughing Matter, 1989, p.27).

Human Condition: ‘Anybody who has the courage to raise his eyes and look sanely at the awful human condition [...] must realise finally that tiny period of temporary release from intolerable suffering is the most that any individual has the right to expect.’ (O’Brien, quoted in Cronin, No Laughing Matter, 1989, p.x; cited in Paul Rice, UG essay, UUC 2001; also quoted in Roger Boylan, ‘“We Laughed, We Cried”: Flann O’Brien’s triumph, in Boston Review, 1 July 2008 - available online; accessed 05.08.2021.) [Note that the ellipsis is the same in all these sources.]

Albert Einstein (Obituary notice on Albert Einstein, in “Cruiskeen Lawn”’, Irish Times, 23 April 1955), offers ‘[a] conspectus of [his] life-work, with a brief accompanying excursis on the application of his discoveries to the science of annihilating the human race’: ‘Physicists for the last fifty years have been concerned to prove that neither Euclid nor Newton knew what they were talking about. There was no such thing as the gravitational attraction between objects as defined by Newton in his Principia Mathematica; and the short distance between two points was not a straight line, if only [because] there was no such thing as a straight line. What was the velocity of the earth? The most subtle and careful experiments proved that the earth was not moving at all; movement means going from one place to another and the earth wasn’t going anywhere, and Newton had established no difference between “motion” in an orderly course and absolute rest. The earth is admitted to be rotating; this is regarded as true motion, but [it is] the cause of what Newton thought was gravitational attraction and what Einstein found to be what he called “acceleration”’. ‘A fundamental Einsteinian postulate is that the age-old concept of space being three-dimensional is mistaken. He insists that it is four-dimension, the fourth dimension being time; he repudiates the separate concepts of “space” and “time” and substitutes “space-time” as an integral thing, and proceeds to speculations in four-dimensional geometry. / The nature of the atom is fairly well known; every atom is a small universe, and it seems fair to deduce that there is really no such thing as matter; as in [?fact] matter and energy are interchangeable, what looks like matter may be taken to be petrified or arrested energy. Nuclear fission (discovered, ironically enough, in Germany in 1939), is the process whereby matter is converted into energy - if the reader will permit so mild a description of the hell-bomb.’

Aesthetics as a mental ailment (The Best of Myles): ‘This is life, and stuffed contentedly in the china bath sits the boy it was invented for, morbidly aware of the structure of history, geography, parsing, algebra, chemistry and woodwork; he is up to his chin in carpediurnal present, and simultaneously, in transcendent sense-immediacy, sensible that without him, without his feeling, his observation, his diapassional apprehension of all planes, his non-pensionable function as catalyst, the whole filmy edifice would crumble into dust. He likes the lukewarm water. He likes himself liking the lukewarm water. He likes himself liking himself liking the lukewarm water. Aesthetics, in other words, is a mental ailment.’ (p.249.)

|

[ top ] |