William Butler Yeats: Commentary (5)

| File 1 | File 2 | File 3 | File 4 | File 5 |

| File 5 | |||

| R. F. Foster Malins & Purkis Joep Leerssen Gerry Smyth Terence Brown |

Brenda Maddox Hermione Lee Rachel V. Billigheimer Selina Guinness Fintan O’Toole |

Jonathan Allison Ann Saddlemyer Peter McDonald Tony Jordan Margaret Mills Harper |

Aaron Kelly Mohammed Meimandi Alistair Cormack Matthew de Forrest Patrick Dowdall |

| Extra: Avies Platt, ‘A Lazarus Beside Me’, in London Review of Books (27 Aug. 2015), pp.29-32 [infra] | |||

| General Index of Commentaries on Yeats |

| ‘Yeats needed to belong to organisations and, once attached, to shape them into the image he desired.’ (R. F. Foster, W. B. Yeats - A Life: The Apprentice Mage (OUP 1997), p.89; quoted in Brendan T. Mitchell, MA Dip., UUC, 2009.) |

| ‘[Yeats] remade an Irish identity in his work and in his life. In the poems he reclaimed Ireland for himself.’ (R. F. Foster, Paddy and Mr Punch: Connections in English and Irish History, London: Penguin 1993, p.227; quoted in Lucinda Gault, MA Dip., UUC, 2010.) |

R. F. Foster, ‘Protestant Magic: W. B. Yeats and the Spell of Irish History’ in Paddy and Mr Punch: Connections in Irish History and English History (London: Allen Lane/Penguin 1993), pp.212-32: ‘[...] Equally Stokerish is Yeats’s interest in Catholic versus Protestant magic. He wrote to Lionel Johnson in 1893: “My own position is that an idealism or spiritualism which denies magic, and evil spirits even, and sneers at magicians and even mediums (the few honest ones) is an academical imposture. Your Church has in this matter been far more thorough than the Protestant. It has never denied Ars Magica, though it has denounced it”. By 1909, however, he had decided that the Protestant mind was readier to accept magic. The pedantry of Irish Catholic education, he wrote in his journal, “comes from intellectual timidity, from the dread of leaving the mind alone among impressions where all seems heretical, and from the habit of political and religious apologetics. This pedantry destroys religion as it destroys poetry, for it destroys all direct knowledge. We taste and feel and see the truth. [219] We do not reason ourselves into it.” This theme appears in the stories he published as The Secret Rose, where magical insight is defined against unthinking Catholicism. Here too there are echoes of Melmoth: the invented text, the esoteric book, the idea of esotericism as aristocratic domination, perhaps - for an Irish Protestant - the reclamation of an élite authority. “The dead”, he once wrote, “remain a portion of the living”. A critic as imaginative as Terry Eagleton might see the crowds of dead people whom Yeats or Elizabeth Bowen discern walking the roads of Ireland as the souls of dispossessed tenants. I do not; but, while accepting the Neoplatonic and Swedenborgian pedigree of ideas about the dead partaking in the life of the living, the particular appeal of the supernatural for Irish Protestants deserves decoding.’ (p.220-21; for full text, see Ricorso Library, “Criticism > Major Authors” > W. B. Yeats - as attached.)

R. F. Foster, ‘Square-built Power and Fiery Shorthand: Yeats, Carleton and the Irish Nineteenth Century’, in The Irish Story: Telling Tales and Making It Up in Ireland (Penguin 2001, 2002), pp.113-26: ‘[Yeats was] grappling with the distinctness of Irish Protestant subculture, and the difficulties of accommodation with the overwhelmingly Catholic complexion of Irish nationalism: areas which Carleton, form radically different origins, had trespassed into before him. Yeats’s relationship to Irish Protestantism is central to his life, though oddly little looked at by scholars. [ftn. Two exceptions are Conor Cruise O’Brien and Vivian Mercier.] It helps explain the depth [121] of his relationship to Augusta Gregory (which far transcended Micheál Mac Liammóir’s description of it as “high priestess and sacred snake” (E. H. Mikhail, Interviews and Recollections, 1777, Vol. 2, p.300). It illuminates the stormy relationship with colleagues within the Abbey Theatre, as well as with audiences across the footlights. And here Yeats found that a culturally nationalist movement could not be above politics in the way he had initially conceived - nor above sectarian politics, when they reared their head. By the time of Synge’s death in 1907, this was clear; and it made him reconsider his ideas about nineteenth-century national literature, marking the point where he diverged from his early reverence for the nineteenth-century Irish novelists whom he had spent so much of his early critical efforts resurrecting. By 1910 he had formally set up an alternative set of artistic standards. His elegiac essay on Synge formally posits the writer’s individual mission against the pressures of nationalist political conformity - what Seamus Heaney (who has walked this ground) has called “the quarrel between free creative imagination and the constraints of religious, political and domestic obligation”. (Introduction, Sweeney Agonistes, 1983.) And this argument is constructed around a reconsideration of the quintessential icon of nineteenth-century literary nationalism, Thomas Davis.’ (p.122.)

R. F. Foster, W. B.Yeats - A Life, Vol. I: “The Apprentice Mage” (OUP 1997): ‘WBY [...] might be located in a particular tradition of Irish Protestant interest in the occult, which stretched back from Sheridan Le Fanu and Charles Maturin, took in WBY’s contemporary Bram Stoker, and carried forward to Elizabeth Bowen: all figures from an increasingly marginalised Irish Protestant middle class, from familes with strong clerical connections, declining fortunes and a tenuous hold on landed authority. An interest in the occult might be seen on one level as a strategy for coping with contemporary threats (Catholicism plays a strong part in all their fantasies), and on another as a search for psychic control.’ (p.50; Foster, ‘W. B. Yeats and the Spell of Irish History’, in Paddy and Mr Punch: Connections in Irish History, [Lane] 1993, pp.212-32; W. B. Yeats - A Life, “The Apprentice Mage”, OUP 1997, p.50; quoted in quoted in Alistair Cormack, Yeats and Joyce: Cyclical History and the Reprobate Tradition, Aldershot: Aldgate 2008, p.40.)

[Note: Cormack writes, ‘Interestingly, Joyce anticipated Foster’s approach to Theosophy, commenting to Stanislaus that it offered a spurious religiosity to disaffected Protestants [Ellmann, James Joyce, 1982 edn. p.99]’. (Cormack, op. cit., p.40.)]

R. F. Foster, W. B.Yeats - A Life, Vol. I: “The Apprentice Mage” (OUP 1997): ‘Waiting for the Millenium, 1896-1898’: ‘[...] For all their emphasis on religious heresy and illuminati traditions, the stories [of The Secret Rose] deal with the choices of the artist. Aherne echoes Lionel Johnson’s refuge in erudition and Catholicism; Robartes follows Russell’s and WBY’s search for enlightenment through vision. The terrain - Dublin, Paris, the west of Ireland - is that traversed by WBY himself in these years; the influences - Luciferianism, the apocalypse, the Cabbala, Rosicrucianism - echo writers like Huysmans whom he had encountered through Symons. Moreover, Blake had taught him that ‘all art is a labour to bring again the golden age’. Revelation is sought, in a milieu dominated by symbols and innocent of humour. Art is seen as spiritual transmutation, achieved through visions with a strong application of Celticist top-dressing (a formula rapidly and efficiently plagiarized by Fiona Macleod). In later revisions the peasantry become progressively less idealized. And it is possible to place these stories in the distinctive Irish Protestant supernatural tradition of Maturin and Le Fanu, where uneasy Anglo-Irish inheritors are caught between the threatening superstructure of Catholicism, and recourse to more demonic forces still, against a wild landscape which they have never fully possessed. / The Secret Rose reflects another arcane subculture too: it was no accident that the language was by turns narcotic and hallucinogenic. WBY had learnt to take hashish with the shady followers of the mystic Louis Claude de Saint Martin in Paris, and with Davray and Symons the previous December. In April 1897 he experimented with mescal, supplied by Havelock Ellis, who recorded that ‘while an excellent subject for visions, and very familiar with various vision-producing drugs and processes’, WBY found the effect on his breathing unpleasant; ‘he much prefers haschish’, which he continue to take in tablets, a particularly potent form of ingestion.’ (See Ellis, “Mescal: A New Artificial Paradise”, in Contemporary Review, 1898.) The stories in The Secret Rose grow out of the underworld of the Savoy as well as the disciplines of supernatural study.’ (p.178; for longer extracts, see Ricorso Library, “Criticism / Major Authors” - W. B. Yeats, infra.)

R. F. Foster, W. B. Yeats - A Life, Vol. II: “The Arch-Poet” (OUP 2003), ‘Bad Writers and Bishops 1924-25’ [Chap. 7] - extracts on A Vision: ‘[...] he had always, one way or another, tried to classify types of human personality. But as outlined in A Vision, his ambition was nothing less than summing up ‘all thought, all history and the difference between man and man’ / It is also a meditation on artistic inspiration, and this links it (as WBY wished) to Per Amica Silentia Lunae. The sun and the moon had for long been his favourite antithetical images, standing for sexual union as well as for complementary supernatural influences. Sometimes rather inconsistently interpreted, they nonetheless dominate the pattern of A Vision. Joyce, characteristically, admired the “colossal conception”, only regretting that “Yeats did not put all this into a creative work.” [Ftn.: Eugene Jolas’s recollection, given in Richard Ellmann, James Joyce, 1982 Rev. Edn., 596n. Foster adds: ‘Parodies of AV would recur in Finnegans Wake.’] / WBY worked from the huge accumulation of automatic-writing transcripts, and the card file in which the Yeatses had attempted to codify the random “knowledge” that they had hit upon: the fruit of his ancient habit of docketing and arranging information, and George’s determination to bring order to his study. Later he would claim he wrote it “for a devoted Catholic and revolutionary who has engaged me in argument since my twenty-third year” - inevitably, Gonne - ‘and for a Scotch doctor in the north of England’: his fellow occultist Frank Pearce Sturm. But, unsurprisingly, the directly personal issues which had brought about the crisis of 1917, and which dominated so many of his questions to George, were not used as illustrations to the system in A Vision: Iseult and George, hare and cat, sit outside the borders of the sacred book, and Maud’s presence remains veiled. Like Farr, Shakespear, Gregory, and Mrs Patrick Campbell, she appears as a nameless “type”. He was also - at this stage - determined to keep George’s contribution undefined. Freudian or Jungian ideas, specifically employed at the time of the interrogations, were also kept out of A Vision, as apparently ill fitted to its deliberately archaic and occult pattern. His method of writing involved a concentrated effort to bring together the great mass of material under intelligible headings, as a way of illustrating the diagrams of recurrence symbolized by the spiralling movements of “gyres” - contracting to a point at which they begin unfolding again in reverse motion, two cones continually interpenetrating. This was the final outcome of his many years’ reading about historical cycles and astrological geometry. / Early drafts suggest that he thought of writing A Vision in dialogue form, so many of his philosophical poems. [...; 281] A Vision represents a little of the best of WBY, and most of the worst. Leaps of imagination, audacious strokes, unforgettably sonorous phrases, and brilliant imagery comes in flashes; he retains his ability to make the esoteric and irrational at once universal and uniquely strange. But far more of the material is ponderous, self-regarding, wildly didactic, inconsistent, and unconvincing. The generalisations on which the archetypes are erected, the arbitrary and self-referencing symbolism, the incomprehensibility of it all to anyone not already verses in his own thought and life, rob it of any general intellectual interest. He came to see this himself with embarrassing rapidity, with the unfortunate result that the great autodidact set himself to producing an alternative version, published twelve years later. / The value inherent in the volume dated 1925 (though published in 1926) is an autobiographical lode.’ [...;’ p.282.) See also under R. F. Foster and Ricorso Library, “Criticism ... Features” [infra].)

R. F. Foster, Paddy and Mr Punch: Connections in Irish and English History, (London: Allen Lane/Penguin 1992): ‘It was necessary for Yeats passionately to adhere to the idea that Sligo people did believe in fairies and talked about them all the time. So they did, of course - to children, as Lily Yeats remembered. The difference was that her brother expected to go on being talked to about them. This tendency is powerfully connected with laying claim to the lost domain of childhood.’ (p.228; quoted in Leerssen, Remembrance and Imagination [...] in Nineteenth Century Ireland, Cork UP 1996, p.193.)

[ top ]

Edward Malins & John Purkis, A Preface to Yeats [1974; rev. edn.] (London: Routledge 1994) - [Chap.] “The Poet’s Reading”: “It is easy to laugh at or be shocked by Yeats’s membership of theses societies [Blavatsky Lodge of Theosophists and Golden Dawn], as were his friends John O’Leary and George Russell, who thought he was wasting his time when he should have been writing. Yet one can now see how vital to Yeats was this searching for a non-materialist world, and the imagery, even though artificially inspired by conscious pictorial symbols, which was fuel to his poetic imagination [sic]. It is the start of Yeats’s lifelong search for symbols and thought forms, after having been brought up by an agnostic father in a world whose poverty of spiritual symbols derived from its sacrifice of the spirit before the claims of the intellect. Yeats feared this separation of spirit and matter in the modern world, and used the Rose as a symbol of harmony which he came to call a “unity of being,” though this was not its only symbolism. His gratitude to these early theosophists and clairvoyants is shown in his subsequent dedication of A Vision in its first private edition (1925), to Mrs [38] MacGregor Mathers herself, one of the few survivors from these times. (pp.38-39.) [Incls. chap.-sect. on A Vision, 65ff.]

Edward Malins & John Purkis, A Preface to Yeats [rev. edn.] (London: Routledge 1994) Before 1924 Yeats had read little philosophy, but in that year he attended lectures in London on Benedetto Croce’s Aesthetic, also reading and annotating Croce’s The Philosophy of Giambattista Vico, translated by R. G. Collingwood. When Yeats was in Italy next year, Mrs. Yeats summarized some of the passages from the other Italian philosophers, as he could not read Italian. One discovery was Vico, a Neapolitan jurist and philosopher-cum-historiographer. [... 53] Of particular interest to Yeats was Vico’s premise, a revolutionary one at the time, that myths and traditions are historical, even though they need not refer to real men; that they are a form of Truth for primitive men, from whom, after the sense and feelings, comes that primary working of the mind, the imagination, which, allied ot Art, he calls poetry. It is easy to understand how Yeats would have joined this to William Blake’s belief in the imagination being born of the passions and being the language of the spiritual kingdom, to which primitive men and children both belong. Previous philosopers had considered the primitive state of nature as savage and brutal, so Vico strikes out a new route with regard to primitive man which Rousseau was to follow later, though he did not go as far as Vico in thinking primitive man was ‘a poet speaking in poetic characters’ [...] / However, more emphasis should be placed on Vico’s cyclical view of movements in both religion and political history. [Gives account of the cycles.] Above all, it is Man who fashions his own destiny, or makes his history in these cycles. [Quotes Yeats:] “Whatever flames upon the night / Man’s own resinous heart has fed.” (Collected Poems, 240.) This removes from Vico’s cyclical theory the depressing determinist philosophy from which Yeats was always trying to escape. (p.54.) [.../] Above all, Vico’s influence shows in the cyclical view of history as worked out in A Vision, with particular reference to certain human types, and which covers all of life: “The Primum Mobile that fashions us / Has made the very owls in circles move.” (CP, 229.) In On the Boiler (1938) Yeats sums up what Vico meant to him by placing him as “the first modern philosopher to discover in his own mind, and in the European past, all human destiny.” Vico’s views [...] recur in Yeats’s late verse, and are an integral part of a consistent pattern in the poet’s thought with [sic] relation to Man and Eternity.’ (p.55.)

Joep Leerssen, Remembrance and Imagination: Patterns in the Historical and Literary Representations of Ireland in the Nineteenth Century (Cork UP/Field Day 1996) [following remarks on the idea of the region in William Allingham (q.v.) and wider reflections on the difference between the region and the metropolis and centre of the nation]: ‘Throughout Europe, the nineteenth-century literary imagination of the countryside is one where peasants are ignorant of metropolitan topicality and speak the language of unchanging proverb and slowly-accumulated natural wisdom. / This attitude was to remain influential in Yeats, who in many respects is a straightforward continuation of Allingham. Allingham himself had freely moved in the Pre-Raphaelite circles of London which Yeats tried to gain access to; his verse had been illustrated by Rossetti and Millais. Allingham’s evocation of the Irish countryside as an idyllic, timeless, traditional community with a hint of faery uncanniness was followed by young Yeats in poems like “The Stolen Children” and The Man who Dreamed of Fairyland”. True, Allingham’s was a influence which Yeats attempted to shed, for it ran counter both to his desire of becoming a nationalist and to his idea of being a serious, philosophical poet; in a way, Yeat’s immersion in Blake was part of his exorcism of Allingham. But if Yeats, in “To Ireland in the Coming Times”, acknowledges ony the names of “Davis, Mangan, Ferguson”, as his Anglo-Irish forerunners, then his is doctoring the record, and the presence of an unacknowledged Allingham comes out towards the end of the self-same stanza: “Ah, faeries dancing under the moon / A Druid land, a Druid tune!” / In fact, young Yeats was structurally in the same position as Allingham, working towards an artist’s career in the empire’s capital. [...]’ (p.187 & ff.)

Further: ‘[...] Yeats’s invocation of Irishness allows him to break out of the historical cul-de-sac. He argues that his imagination is not part of English decrepitude since it has been fed on the still-unused, fresh and pristine material of irish myth and folklore. The fact that Ireland is backward, outside the pale of English historicity and English modernity, becomes a rejuvenation formula - much as, in later life, monkey hormones were to be his answer to the march of time within his own metabolism. [Quotes ‘... we are a young nation with unexpected material lying within us ...’ (“Nationality in Literature”, 1893; Uncollected Prose, ed. Frayne, Vol. I, pp.266-75 [no page ref.].) Thus, Ireland is not ony old and timeless but also young. The falling-out between O’Connell and Young Ireland, when O’Connell said that he was for Old Ireland, is here short-circuited in a highly effective formula where Ireland can simultaneusly benefit from virtues of youth and old age.’ (Leerssen, op. cit., 1996, p.194.)

[ See further notes from Leerssen, Remembrance and Imagination [...] (1996) - Commentary (4) - as supra. ]

[ top ]

Gerry Smyth, Decolonisation and Criticism: The Construction of Irish Literature (London: Pluto Press 1998): ‘[Yeats] hoped to maintain the centrality of Anglo-Ireland to the emerging modern Irish nation by engaging in a critical discourse through which he could define the relationship between culture and nation, and thus shape what could legitimately be said about each.’ (p.73.) ‘It is [the] anti-materialist strain that constitutes Yeats’s most important contribution to contemporary Irish cultural politics.’ (p.74). ‘The paradox underpinning the statement [as infra] is the paradox of liberal decolonisation: authentic national experience must be possessed of a “supplementarity” which will secure for Anglo-Irish a role in contemporary Ireland.’ (p.75.) Further: ‘Liberal-decolonising [75] strategy of this kind was always going to be of only limited use in the construction of an Irish identity and an Irish history, because the terms in which that identity and that history could be articulated were thoroughly informed by metropolitan values and the logic of supplementarity through which English colonialist discourse functioned.’ (Ibid., 75-76.)

[Here quotes Yeats, citing Vinod Sena, W. B. Yeats as Poet and Critic, Macmillan 1980, p.8: “[T]he true ambition is to make criticism as international, and literature as national, as possible.”] Yeats denies the authenticity of a criticism which springs from its own object, or an art which evokes its own criticism. Criticism must vindicate Anglo-Irish experience by having a relationship with its cultural object which is at once congruent and discrepant.’ (p.75.)

Terence Brown, The Life of W. B. Yeats (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1999): ‘A Visionwas Yeats’s summons to the Irish state to find its spiritual destiny as an antithetical nation that would prefigure a general reversal of a materialist world order. ... Yeats hoped that conflict, the dominant subject of his prophetic book, would be the catalyst of spiritually invigorating change.’ (Ibid., p.311; quoted in Bernard McKenna, “Yeats, “Leda,” and the Aesthetics of To-Morrow: “The Immortality of the Soul”’, in New Hibernia Review, 13, 2, Summer 2009, p.19.) [Cont.]

Cont. (Terence Brown, The Life of W. B. Yeats, Gill & Macmillan 1999): ‘Yeats’s association with his Swami [Shri Purohit Swami] and the reading and study it provoked account for the deliberate orientalising of his late poetry. As they had been at the outset of his career, Ireland and India are venerated by the poet in his final years as very ancient cultures in which the oldest wisdom of the world took deep root in traditions of pilgrimage, of sacred rivers and lakes, of holy mountains. […] Yeats’s late poetry inhabits a kind of world geography in which ancient Ireland - with its mystic sites, Celtic crosses, burial mounds - is made to seem the spiritual kin of India, Japan, China, Alexandrine Egypt. This easily comparativist perspective gives to Yeats’s last collections of verse an imaginative spaciousness and universalism that is the antithesis of the truculent Anglophobic nationalism that some of his late ballads also indulge, and to the crude elitism of his social attitudes in some of his poems. Where Yeats’s early poetry, in the act of imaginative appropriation, had made the English language take account of the mysteriously otherness of Irish place-names, locales and mythologies, this late poetry anticipates English as the language of a liberated post-colonial world in which ancient, shared identities could be rediscovered in the language of dispossession. In this emancipatory freeing of [353] English from its tribal and geographic roots, and from colonial oppressiveness, politics and nation became subsumed in a mood of all-encompassing spirituality which knows that sub species [sic] aeternitatis and in the light of human destinies, a narrow nationalistic self-interest fades into insignificance.’ [Cont.]

Cont. (Terence Brown, The Life of W. B. Yeats, Gill & Macmillan 1999) [quotes Yeats, “General Introduction” (1937)]: ‘I am no Nationalist, except in Ireland for passing reasons …’] Yet late Yeatsian orientalism is not just a matter of sexual theology and technique, gender exchanges and enhancing, comparativist perspectives. […] For he knew that Hindu mysticism in its ascetic form seeks to “pass out of […] three penitential circles, that of common men, that of gifted men, and that of the Gods” to find a cavern on a holy mountain “and so pass out of life.” [Essays & Introductions, p.469.] To western ways of thought such ascetic intensity is distinctly unappealing and can be difficult to distinguish from nihilistic life-denial. And in Yeats’s late poetry the way of the east can indeed seem the way of terrifying negation that leads to the knowledge that reality has its basis in non-being.’ [Quotes “Meru”]. ‘In this mood the East for Yeats in his last years is the Buddha, whose ‘empty eye-balls knew / That knowledge increases unreality, that / Mirror on mirror mirrored all the show’ (“Statues”). Eastern thought intensified his growing fear, as death approached, that there was nothing behind the “superhuman mirror / Resembling dream” (“The Tower”) that man had made to disguise from himself the truth of nihilism from “the desolation of reality”. (pp.353-54.)

Brenda Maddox, Yeats’s Ghosts: The Secret Life of W. B. Yeats (NY: HarperCollins 1999), takes issue with the editors’ of the Vision Papers’ assumption that the phantasmal cast of the Automatic Script (Aymor, Thomas of Dorlowitz, Democritus, Leo) are real - viz., ‘Aymore [may] have been thinking of the Yeats’s imminent visit to Ireland [Yeats’s Vision Papers, Vol. 1, 18]’ and remarks: ‘Phrases such as these, even if used as a matter of convention, suggest that “Aymor” could inform, “Thomas” could thing, and that “Leo” could stay George Yeats’s hand. I do not believe this. I see the Automatic Script as an oblique form of communication between a young wife and an ageing husband who did not know each other very well and needed it for things they could say to one another in no other way.’ (p.xvii.) Further, ‘If feminism has yielded a new Yeats, so too has molecular biology. Advances in the understanding of genes has shed a kindlier light on the promise that of eugenics held for pre-Holocaust generations.’ (p.xviii.) Maddox reprints photograph of Edith Heald sunning herself without her blouse in a garden at The Chantry House in Steyning, Sussex (jointly built with Nora Heald, also determinedly single), watched comfortably by Yeats in a deck-chair [pls.] Yeats was brought there by Edmund Dulac in April 1937; first acquaintance, 1910, renewed 1929 (then writing in Daily Express). Note: Elizabeth B. Cullingford writes that the Script helped Yeats make sense of his sexual life: ‘she points out how it directs Yeats’s attention to the need for sexual satisfaction of ‘the medium’ (his wife).’ (See Cullingford, Gender and History in Yeats’s Love Poetry, 1993, p.111.)

Hermione Lee, review of Terence Brown, The Life of W. B. Yeats, and Brenda Maddox, Yeats’s Ghosts, in NY Times, “Book Review” (21 Nov. 1999), reemarks on Maddox indicate that she is sympathetic and humane about George at Yeats’s expense, casting him as ‘a compulsive masturbator’. His Steinach operation, Frank O’Connor remarked, was ‘like putting a Cadillac engine in a Ford car.’ Lee regards much of the book as ‘crude stuff’. Maddox is a sceptic about the bones in Drumcliff. Both authors quote Yeats’s last poem, “The Black Tower”: ‘There in the tomb the dark grows blacker, / But the wind comes up from the shore: / They shake when the winds roar,/ Old bones upon the mountain shake.’ Lee calls both books worth reading and flawed, but awaits the second volume of R. F. Foster’s life of Yeats [2003] which ‘magisterially succeeds by adopting a mode of scrupulous attention, refusing to accede to myth-making.’ (See also under Terence Brown, supra; and see longer extracts from Maddox, op. cit., in RICORSO Library, “Criticism”, infra.)

Rachel V. Billigheimer, Wheels of Eternity: A Comparative Study of William Blake and William Butler Yeats (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1999): ‘It appears that the circle, rather than the gyre, should be regarded as fundamental to Yeats. The circle is an archetypal symbol. Since it is primeval, it is a universal expression in all cultures of the basic, moving pattern of life. Yeats also aspires to an immutable, transcendent state of perfection such as that put forward by the French symbolists Mallarmé and Maeterlinck [sic]. In addition there are the magical elements of an immortal Irish mythical world […] the magical, circular dance, for instance, which treads to the rhythm of the Wheel of Eternity, is a dominant symbol in Yeats. It embraces the moving forces of love and life and the tragic vision of life and earth, creation and destruction.’ (p.10.)

| Cont. (Rachel V. Billigheimer, Wheels of Eternity[...] William Blake and William Butler Yeats (1999): ‘From the division of subjective and objective we have the concept of the anti-self and the self, corresponding to the Emanation and Spectre in Blake, which are characteristic of the division of mental states in all societies and individuals. We may see the symbolic circle in Yeats signifying the struggle of the self and anti-self as lending itself to the Jungian interpretation of the mandala indicating complete self-integration. (p.11.) |

|

[ top ]

Selina Guinness, reviewing Jefferson Holderidge, Those Mingled Seas: The Poetry of W. B. Yeats, the Beautiful and the Sublime (UCD Press 2000), 258pp., writes: ‘A key trope in Enlightenment philosophy, the sublime is the sudden apprehension of extreme beauty, the viewer mixing positive feelings of wonder and negative feelings of terror in almost equal parts, and notes the Holderidge ‘painstakingly outlines the differences between Burke’s ideas of the negative sublime as a violent disruption of the beauty expressed in the harmony of social order, and Kant’s idea that the sublime offers a glimpse of transcendental freedom along the edge of the material world.’ Further remarks that Holderidge convincingly argues that Yeats’s poetry describes the unstable ground where these two views meet, and identifies as the central argument Holderidge’s attempt ‘to illustrate the various ways in which Yeats eroticises the divine’. Notes adroitness with ideas of Lyotard, Kristeva and Adorno but laments lack of engagement with feminist critques of Enlightenment discourse, nameing Michele Le Doeuff, and greater engagement with Margaret Howes and Elizabeth Butler Cullingford. Considers the book a standard for years to come.’ (Irish Times [12 Aug. 2000])

Selina Guinness, review essay on Ann Saddlemyer, becoming George: The Life of Mrs W. B. Yeats (NY & Oxford: OUP 2002), in Dublin Review, No. 9 (Winter 2002-03), pp.119-26, writes: ‘In 1913 Yeats had asked Georgie [Hyde-Lees] to go the the British Museum and cross-check German references that cropped up in the script of Elizabeth Radcliffe. Wildly excited by the scraps of Chinese, Greek, Welsh and ancient Egyptian that were written by a ghostly hand between two slates bound tightly together, in reply to his silent questions, W. B. had spent the first two years of their acquaintance obsessively investigating “Bessie’s” script, convinced that at long last he had proof of a genuine [120] psychic experience.’ (pp.120-21.) Also quotes “The Gift of Harun-Al-Rashid” in which Yeats’s alter ego formulates one hope regarding Georgie’s apparent powers: ‘All, all those gyres and cubes and midnight things / Are but a new expression of her body / Drunk with the bitter sweetness of her youth.’, and remarks: ‘But just as, in this complex epithalamion, doubts about the Bedouin bride’s “unnatural interest in [my] books” [CP, 518] threaten to taint the purity of revelation with a whiff of printer’s ink, so too Georgie’s learning forced its author to recognise that spirits could take their shape only from the material they found ready and waiting in the subconscious of the medium.’ (Ibid., p.121.)

Fintan O’Toole, reviewing Nicholas Grene, The Politics of Irish Drama (Cambridge UP [2000]), in The Irish Times (11 March 2000) [Weekend], writes: ‘Yeats famously asked “Did that pay of mine send out / Certain men the English shot?” which, in these less romantic times, Paul Muldoon replied with the rhetorical question, “If Willie Yeats had saved his pencil lead / Would certain men have stayed in bed?”’ Further: ‘[...] he self-important delusions of writers who believe that they shape political ends merely by imagining them invites a kind of comic deflation. And yet, Yeats’s question was not entirely a product self-delusion. / Modern Irish history has indeed been influenced both by the images of Ireland invented by poets and playwrights and by the failure of reality to live up to those ages. Cathleen Ni Houlihan may not have sent Patrick Pearse into the GPO in 1916. Pearse himself wrote plays and imagined the Rising as a dramatic ritual, part religious sacrifice, part street theatre. And in the year of the Rising he wrote, as Nicholas Grene reminds us, that if he had seen Cathleen Ni Houlihan as a boy, he “should have taken it not as an allegory but as a representation of a thing that might happen any day my house”. The line between Irish theatre and Irish history is not so clear after all.’ (See full text, infra.)

Fintan O’Toole - on the unpublished adolescent play of 1884, Love and Death -digitised by Burns Library of Boston College: ‘Getting from where he was at 18 to where he would be at 40 is not a process of finding new themes that resonate with his imagination: many of them, not least the intertwining of love and death, are already in his head. It is a process of finding a context in which those images have power. / That context is Ireland, and the final fascination of Love and Death is in seeping how completely absent it is for the 18-year-old Yeats. The only Irish thing in the whole manuscript is the name of the stationer on the inside cover of the notebooks: W Carson, 51 Grafton Street. Without it, no one doing a blind tastingtof the play would guess that its author was other than English. All of the influences and cadences are from a purely English tradition. / It was that discovery of Ireland that allowed Yeats to make his fey fantasies and overheated myths connect with politics, with folklore, with something beyond the books he was reading. He was able to shift from Ginevra to Cuchulainn, he could use the same pasion for myth. But now something real was at stake, and his language had to acquire its stringency and danger. Yeats did a lot for Ireland, but when you see how easily he might have amoutned to nothing more than a minor pre-Raphaelite, you realise the favour worked both ways.’ (In The Irish Times, 28 April 2012, Weekend Review, p.9.)

Jonathan Allison, ‘W. B. Yeats: Space and Cultural Nationalism’, in ANQ [Univ. of Kentucky], 14, 4 (Fall 2001), p.55-66: ‘W. B. Yeats’s sense of landscape, particularly his sense of certain places (Innisfree, Coole, Ballylee) as cherished landmarks (and even sacred places), is inevitably linked to the poet’s ideas of home and nation. Importantly, thes places were sites of linkage between all that Yeats valued in the Anglo-Irish Ascendancy and in peasant folk culture. These sites are therefore meeting places, locations of cultural unity and energy, reg enerative sources for his imagination and for the nation at large.’ (p.55; quoted in Carl Campbell, MA Dip., UUC 2009.)

[ top ]

Ann Saddlemyer, Becoming George: The Life of Mrs W. B. Yeats (Oxford: OUP 2002) [Chap. 6: “Forest Row”]: ‘What did they themselves believe? “Overwhelmed by miracle as all men must be when in the midst of it” (Intro., Vision, B.), Yeats was by nature and inclination receptive to the conviction that in the trace state such revelations could occur. He had, after all, decided that “the ER case” had finally proved spirit identity. What Elizabeth Radcliffe’s scripts and his many sitting with other mediums had not offered was [126] “speculative power, or at any rate not equal to the mind’s action at its best … [it is] only in speculation, wit, the highest choice of the mind that they fail”. (Journal, July 1913; Reflection by Mr Yeats … transcribed by Curtis Bradford, Cuala 1970, pp.51-52.) There was no question of the scripts provided by George lacking such qualities. Nor was there any doubt that these powers were doubled by the “Wisdom of Two”. Yeats’s note to his poem “An Image from a Past Life”, which is based on a shared dream he and George experienced at Ballylee, offers one explanation: “No mind’s contents are necessarily shut off from another and in moments of excitement images pass from one mind to the other with extraordinary ease, perhaps most easily from that part of the mind which for the time being is outside consciousness … The second mind sees what the first has already seen - that is all.” (Quoted in Jeffares, W . B. Yeats: Man and Poet, p.210.) / The concept of thought transference or mental telepathy [coined by Frederic Myers] had been a major concern of the Society for Psychical Research ever since its founding. […] (pp.126-27.)

Cont. (Ann Saddlemyer, Becoming George): [...] ‘Although I am reluctant to claim what is commonly thought of as mystical powers for George Yeats, it would appear that, in her entranced state, something did indeed “grasp her hand”. That something was akin to the ecstatic state in which, as Northrop Frye describes it, “the real self, whatever reality is and whatever the self is in this context, enters a different order of things fro that of the now dispossessed ego.” and ‘all the doors of perception in the psyche, the doors of dream and fantasy as well as of waking consciousness, are thrown open.” (Words with Power, pp.82-83.) So slender is the thread between this and the normal state that anything might disrupt concentration, which would explain in part the script’s frequent annoyance with Willy’s insistent questioning and persistence in pursuing one line of thought. While still in the Ashdown Forest Hotel the control insisted, “when you are doubting we begin to doubt too”, and later, “I don’t like you misdoubting script as it upset [sic] the communication. Much better not ask for facts No No but never for veryfactions [sic]’ (YVP, I, 61 & YVP, Vol. II, 454; here p.131.) [...] ‘Whether you choose to call the extraordinary phenomenon that occurred in Ashdown Forest subconscious direction, cross-dreaming, extrasensory perception, subliminal consciousness, split subjectivity, telepathy, clairvoyance, channelling, psychic transcription, “faculty X”, “Mind Energy” [e.g., Colin Wilson, et al.], or plain hocus-pocus, the results are obvious. Clearly there were strong psychological advantages and equally strong emotional benefits to the role Georgie consciously chose to play in selecting automatic writing as her creative medium: as they worked out the system of what could become A Vision, George’s place in Willy’s affections was assured and their marriage forged with a confidence and trust in each other’s frank responses which would last until death. More than that ‘friendly, serviceable & very able’ domestic partner he had hoped for, she was immediately established as the voice of truth, and for the rest of their lives together would continue to serve as unquestioned extension of his senses. If poetry was the essence of his creative genius, then the automatic writing, whether consciously initiated or not, became the essence of hers. In helping provide those metaphors for poetry, might not the poet in turn have become her form of creation?’ (p.133; for longer extract, see Ricorso Library, “Criticism” / Major Authors - W. B. Yeats, infra.)

Peter McDonald, ‘Yeats’s Poetic Structures’, in Serious Poetry: Form and Authority from Yeats to Hill (OUP 2002) examines the subtle ways that the metaphor of the stanza - the magnificent rooms of Yeats’s major poems - serves Yeats’s treatment of actual structures, great houses and towers. When, at the end of “Coole Park, 1929”, Yeats looks forward to a day “When all those rooms and passages are gone”, he invokes an enduring “here” - “Here, traveller, scholar, poet, take your stand” - which is really the stanza itself. ‘“Here” is a place the poem makes, and which the stanza builds’, McDonald rightly says. And yet, Yeats’s form not only competes with natural ruin; McDonald shows that it also, in late poems like “An Acre of Grass” and “The Curse a of Cromwell”, contains and encodes ruin. In the latter poem, for example, McDonald suggests that the introduction of a ballad refrain ‘brings into play a very different kind of repetition ... from the returns and changes of the rhymes in Yeats’s grand stanzas. Here, the refrain is the return of the thing that simply refuses to go away, the question that repeats and repe4IS because it cannot be answered.” (See Adam Kirsch, review of same in Times Literary Supplement, 29 Nov. 2002, p.6.)

Anthony [Tony] Jordan, W. B. Yeats: Vain, Glorious, Lout (Westport Books 2003): interview-review in Books Ireland (Summer 2003): a ‘plain-speaking and less than flattering perspective’; Yeats “felt nothing” at the death of his mother and reluctantly agreed to share cost of plaque; resisted Lollie’s teacher-training plans and warned that higher education turned women into “loud chatterers”; makes much of influence of Neitszche, recommended to Yeats by John Quinn in 1902; wrote to Olivia Shakespear [here Shakespeare] urging “the despotic rule of the educated classes as the only end of the country’s troubles”; appeared at Kildare St. Club in blue shirt in support of early fascism; narrates anecdote of Sir Ian Hamilton, a cousin of Lady Gregory and a soldier, who met Hitler and recorded his reactions: “Where ever have I heard someone speak like this? Who could it have been? Then suddenly, as he spoke of his nightingales, the mirror of memory flashed and there I was listening again to Yeats”. (p.141.) See also extracts from Anthony J. Jordan, The Yeats Gonne MacBride Triangle (Westport 2000), in Ricorso Library “Criticism / Sundry Critics” [infra].

Margaret Mills Harper, Wisdom of Two: The Spiritual and Literary Collaboration of George and W. B. Yeats (Oxford: OUP 2006): ‘Many readers over the years have assigned GY biographical importance but little literary relevance other than the oddity of having functioned as medium in the occult revelations that she and her husband received. In turn, the spiritual knowledge that the Yeatses believed they gained through automatic writing and other related methods is often acknowledged for having inspired certain poems and plays, but tends not to be interpreted as having much critical value. Yet the famous Irish poet and his work were both changed utterly by a young Englishwoman with magical interests, a gift for automatic writing and a quietly imposing intelligence. As Terence Brown puts it, since the start of the script, ‘Yeats’s creative work had been increasingly dependent on a collaborative engagement with is wife’s mediumistic powers.’ (Life, p.261.) Her work affected his, most profoundly in the 1920s and 1930s, decades during which he produced his best writing.’ (p.10.)

| ‘The WBY who presents A Vision and has a secondary role as a character in some of its bewilderingly prominent framing stories and poems is in fact several Yeatses, sliding between subject and object positions, who refer to each other in complex ways that are uncertainly and simultaneously serious and comic. Moreover, A Vision is two books, separated in time by some eleven years, which refer to each other in terms that are equally slippery and equally performative. A duality or multiplicity of subject makes itself felt throughout this/these work(s), in point of view, rhetoric, the relation of framing material to what is inside the frames, and within the content of the system itself (so that one gyre becomes two at the least touch, for example.) This dramatic doubling and multiplying, no less integral to the book than it has been maddeningly difficult for many readers, may be analysed also in terms of the joint endeavour that was its inception and elaboration.’ (p.14.) |

| Cont. (Margaret Mills Harper, Wisdom of Two, 2006): ‘[... D]iscussion of the Yeatses’ occult experimentation still tends t begin, and often to end, at the question, Did they, or Do you, believe it?, with lines between camps drawn on the basis of the answer to the latter. The Yeatses themselves were by no means distracted by such compulsions. / Saddlemyer’s detailed psychological account of what might have happened in the nightly sessions draws attention to the heterogeneous sources of what she suggests may have been self-hypnosis. Saddlemyer also points to two interesting facts: that GY herself apparently first used the critical word fakery in association with her first attempt at automatic writing; and that she was keenly aware that, having done so, the word would damage her reputation. As she told A. Norman Jeffares, ‘the word “Fake” will go down to posterity’. (Saddlemyer, Becoming George, p.103.) Interestingly, GY’S use of the term occurred in the context of working with Yeats scholars (notably Virginia Moore and Richard Ellmann) who took the script seriously and were working to understand its elaborate ideas as such, hardly efforts they would have made if they thought that GY had simply made everything up. On the contrary: her honest admission added to the complexity of the affair. (p.21.) / Nor are the synecdoches only for the uncanny, that lack of fit between an imagined perceptible world and an unimaginable real so common in the modern period, and so commonly expressed through the instability of texts.’ (See Pref. to Julian Wolfreys, Victorian Hauntings … [ &c.], 2002, citing Jean-Michel Rabaté, The Ghosts of Modernity, 1996, et al.) (p.24.) |

| ‘Yet the naming of the instructors is both consistent and insistent, no less than if each control were a queen or maharajah. This state of affairs suggests that it is centrally important to the script both that it be filled with authors and, equally, that they signify something other than authorship in the usual sense. Like other authorial presences, the script and the Vision documents, as well as A Vision itself, [149] including daimons, frustrators, Giraldus, Robartes, and ‘Yeats’, they suggest both their own ephemeral state and that such named agents betray little of the hidden authority behind them; it is impossible to gain sure access to that authority. The communicators bespeak a text that seems to resist control and practically to author itself, by which odd phrase I mean hold discourse with and against the Yeatses as well as its other producers. In the documents that comprise the automatic script, meaning is finally generated not through a tight fit between hand and pen, or even a loose impression of an authorial presence guiding the whole, but by an unworkable mélange of symbolic excess and omission in which the valid is indistinguishable from the unreliable and both are in active engagement with writers or readers, automatic or otherwise. The automatic script relocates agency as it overdramatises and under-realises it, disjoining both authority and identification in the process. In this regard, the manuscripts and notebooks throw responsibility for their sense and status as meaningful discourse on to those of us who have contact with them, slyly offering the recommendation that interpretation is action and suggesting that this was always so. These scripts, unlike their theatrical namesakes, play scripts, do not direct their actors to perform for us: instead, they meet our gaze, and thus vanish from our subjective space. (p.150; end Chap. 2; for longer extracts, see Ricorso Library, “Criticism / Major Authors” - W. B. Yeats, infra.) |

Margaret Mills Harper, ‘Yeats and the Occult’, in Majorie Howes & John Kelly, eds., The Cambridge Companion to W. B. Yeats (Cambridge UP 2006): ‘To indicate the dynamism of Yeats’s long career it would be best to use a continually moving figure, perhaps turning or spinning rather than moving in a single direction, to indicate that movement is not necessarily progress, that favorite concept in popular thought since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. Yeats despised the notion of progress, much preferring the countering notion that older, even ancient, was very likely better than new and improved, in most matters. The figure might also need to be double, to give the sense that oppositions or antitheses define Yeats more faithfully than single positions. The power of Yeats’s poetry resides to a large degree in its willingness to make visible its internal struggles and vacillations, between such poles as self-delighting art and political conflict, public and private spheres, love and hatred, faith and doubt, natural and supernatural, the interior self and the dramatised mask, detachment and desire. The one always engages with the other, like partners in a dance. / Our figure for Yeats would need a central point, a focus of greatest intensity or centre of gravity that keeps the rest of the pattern in motion. If Yeats were labelling the diagram, there are several possible forces that he would identify as such a hub. One of the most likely candidates would be his lifelong exploration of and belief in occult studies. A great many of the elements composing what is distinctively Yeatsian radiate outward from a seeming miscellany of folk-religious, psychical, spiritual, and magical ideas and practices. It is as close to a centre as Yeats comes, even though, to use a metaphor from “The Second Coming”, it cannot hold, in the sense of arriving either at certainty or internal consistency. Indeed, malleability is part of the attraction.’ (pp.144-45.)

[ top ]

Aaron Kelly, Twentieth-Century Literature in Ireland: A Reader’s Guide to Essential Criticism (London: Palgrave Macmillan 2008) [quotes Yeats on ‘that melancholy which made all ancient peoples delight in tales that end in death and parting, as modern peoples delight in tales that end in marriage bells; and made all ancient peoples, who, like the old Irish, had a nature more lyrical than dramatic, delight in wild and beautiful lamentation’ (Elements of Celtic Literature, 1902; as supra, and remarks]: ‘We can discern here the implacable anti-modernity that is given directly political shape in a play such as Yeats’s Cathleen ni Houlihan (1902), wherein Michael Gillane is required to renounce the material world of money, possessions and marriage in order to answer the lament of his nation personified as Mother Ireland or Cathleen. What is truly Irish, it is implied, is either that which has been uncontaminated by the material world, or that which is once more prepared to renounce the petty concerns of that world. Hence, what Ireland needs to restore to itself is not to be found in Dublin or Belfast for example, but in a realm where the artist may commune with a rural, peasant people themselves at one with nature. / It can be pointed out that the melancholy attributed to the Celtic peasant not only by Yeats but also by [Matthew] Arnold and [Ernest] Renan before him is particularly disingenuous, to put it mildly, in an Irish context, given the Famine (which directly impinges on Arnold’s lectures) and a broader history of dispossession, poverty and suffering. The social and historical conditions producing a vast Irish folk and ballad tradition of loss and lament are thus recoded and decontextualized as an immemorial metaphysical disposition. Yeats’s sense, in the above passage, that it is he and the urban intelligentsia who suffer “penury”, inverts the reality of social inequality in assembling a model of spiritual debasement designed to [10] transfigure the rural poor into keepers of cultural riches. [...] His use of the peasantly as a point of access to an “ancient world” also discloses that Yeats’s revival mission was to repair a rupture in Irish history and tradition caused by Ireland’s subjugation and the imposition of the British culture that he sees as the vehicle of modern, materialist corruption. While the marginalization of the Irish language and the fragmentation of Irish culture prevent any sense of cultural continuity, Yeats eandeavours to restore and recuperate out of that discontinuity, if not a unitary tradition, then a unity of purpose that may finally make Irish culture whole again in the present. So the lessons and achievements of antiquity that have been preserved in however disparate and fragmentary a form, the remaining repositories of Irish culture, may speak once more and assume their full meaning in the present and in the transformation of Irish national life.’ (pp.10-11.)

Mohammed Nabi Meimandi, ‘“Just as Strenuous a Nationalist as Ever”: W. B. Yeats and Postcolonialism: Tensions, Ambiguities, and Uncertainties” (PhD Thesis: Bermingham Univ. 2007) - Summary: “This study investigates William Butler Yeats’s relationship to the issues of colonialism and anti-colonialism and his stance as a postcolonial poet. A considerable part of Yeats criticism has read him either as a revolutionary and anti-colonial figure or a poet with reactionary and colonialist mentality. The main argument of this thesis is that in approaching Yeats’s position as a (post)colonial poet, it is more fruitful to avoid an either / or criticism and instead to foreground the issues of change, circularity, and hybridity. The theoretical framework is based on Homi Bhabha’s analysis of the complicated relationship between the colonizer and the colonized identities. It is argued that Bhabha’s views regarding the hybridity of the colonial subject, and also the inherent complexity and ambiguity in the relationship between the colonizer and the colonized can provide us with a better understating of the Irish poet’s complex interactions with Irish nationalism and British colonialism. By a close reading of some of Yeats’s works from different periods of his long career, it is shown that most of the time he adopted a double, ambiguous, and even contradictory position with regard to his political loyalties. It is suggested that the very presence of tensions and uncertainties which permeates Yeats’s writings and utterances should warn us against a monolithic, static, and unchanging reading of his colonial identity. Finally, it is argued that a postcolonial approach which focuses on the issue of diversity and hybridity of the colonial subject can increase our awareness of Yeats’s complex role in and his conflicted relationship with a colonized and then a (partially) postcolonial Ireland.’ (Accessible at Bermingham University archive - online; accessed 06.05.2011.)

Alistair Cormack, Yeats and Joyce: Cyclical History and the Reprobate Tradition (Aldershot: Aldgate Publishing 2008): ‘[...] Yeats’s encounter with Vico comes with a good deal more ideological baggage [than Joyce’s]. Joseph Hone recalls a morning spent in Rome with Mrs Yeats in 1925, “searching the bookshops ... for works dealing with the spiritual antecedents of the Fascist revolution ...” (Hone, W. B. Yeats, 1962, p.368.) Through this interest, Yeats became familiar with Croce’s Estetica, and, in [R. G.] Collingwood’s translation, his Philosophy of Giambattista Vico [1923], which he read and annotated. He also had his wife read and summarise for him Gentile’s La Riforma dell’ Educazione and Teoria generale dello Spirito come Atto puro. Thus, Hone could argue “his philosophic as opposed to his occult background was formed by the modern Italians, with a foundation of Plato and Plotinus, Boehme and Swedenborg.” (Hone, op. cit., p.368.) [Cormack, op. cit., p.25.]

[Quotes Yeats: ‘Students of contemporary Italy, where Vico’s thought is current through its infuence upon Croce and Gentile, think it created, or in part created, the present government of one man surrounded by just such able assistants as Vico foresaw.’ (Explorations, 1962, p.354.)]

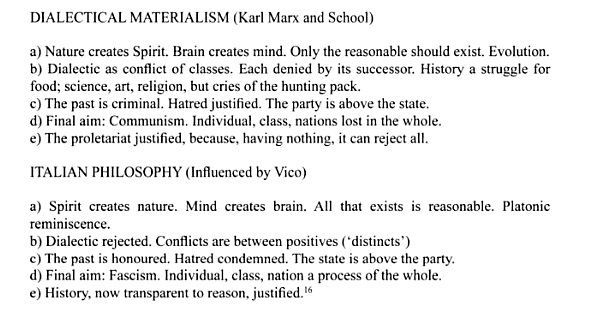

| Cont. (Alistair Cormack, Yeats and Joyce: Cyclical History and the Reprobate Tradition, 2008): Cormack remarks that Yeats did not know that Croce had distanced himself from Italian Fascism [Elizabeth Butler Cullingford, Yeats, Ireland and Fascism, Macmillan 1981, p.151] and adds that ‘Vico’s opposition to materialism and scientific positivism were analogous in Yeats’s mind to Mussolini’s opposition to Marxism.’ (Cormack, p.25.) Reproduces Yeats’s chart of differences between “Dialectical Materialism (Karl Marx and School)” and “Italian Philosophy (Influenced by Vico)” in which the metaphysical outlook in one (”Nature creates Spirit. Brain creates Mind”) is opposed to the metaphysical outlook in the other (“Spirit creates nature. Mind creates brain.”), each list respectively ending with “Final aim: Communism”, and “The proletariat justified because, having nothing, it can reject all”, and “Final aim: Fascism”, and “History, now transparent to reason, justified”. (Appendix in Jeffares, W. B. Yeats: Man and Poet [3rd edn., Dublin 1996, pp.325-26; here p.25.) [Note: the list runs a) to e) under each heading with strictly parallel but antagonistic statements.) |

| ‘This aphoristic piece shows the limitations of Yeats’s understanding of fascism and, in particular in the case of the first part (e), his complete ignorance as regards proletarianism; the notion that fascism honoured the past and condemned hatred shows a gross blindness to political reality. However, this piece does give us an insight into his reasons for thinking fascism a valid realisation of the idealist philosophy, which, in his understanding, sprang from the version of nationalism that he espoused pretty much throughout his life. In fascism Yeats found a reality that he desperately wanted to be a proof for his eccentric theories. And the end, the philosophy expounded above, which includes a valorisation of positive contraries, a defence of particularity in the face of materialism and a notion of spirit containing nature, is closer to Blake than Mussolini.’ (p.26.) |

Cont. (Alistair Cormack, Yeats and Joyce: Cyclical History and the Reprobate Tradition, 2008): Cormack notes that Yeats adds to the above piece, “Fascism inadequate” [Jeffares, op. cit., p.326], continuing: ‘- an inadequacy stemming from its failure to treat itself with the irony that Vico applies to all epochs ... In the final version of A Vision the importance of positive contraries outweighs the allure of authoritarianism. / Thus, at first look, for Yeats, Vico offered a means of opposing Marx with an idealist philosophy that had a contemporary flavour. [...] After an equally superficial look at Joyce, we might argue that Vico offered a convenient means of schematising the uncontrollable data of history. It is interesting to note that the political implications of the New Science offered by Yeats and those suggested by Joyce’s work follow the patterns of its reception since the late eighteenth century. The children of 1789 and German counter-revolutionaries found lessons in it, as did the fascists Gentile and Marx himself; it seemed that the political implications of this highly polysemic work have been undecidable.’ [Ftn. See Peter Burke, Vico, Oxford 1985, pp.3-9.)

See Cormack’s transcription of Yeats’s rationale of Italian philosophy: Cont. (Alistair Cormack, Yeats and Joyce: Cyclical History and the Reprobate Tradition, 2008): ‘[...] For Yeats, Vico provided a means of validating the approach to history he had begun to outline in the first edition of A Vision.’ [Notes that Yeats wrote ‘I mock Plotinus’ thought [... &c.] immediately after his encounter with Vico.’ (p.26.) [See longer extracts in RICORSO Library, “Criticism > Major Authors” > Yeats - via index or as attached.]

[ top ]

| Matthew deForrest, ‘Yeats and the New Physics’, in The Living Stream: Yeats Annual, 18, ed. Warwick Gould [Special Iss.] (2013), pp.297-312:— |

[...] By 1925, the year when A Vision was published, Einstein had won the Nobel Prize in Physics. His work on Relativity had also had almost a decade to impact popular culture and be part of the arguments in several of the books that Yeats read and, at times, annotated. Indeed, Yeats owned a copy of Einstein’s 1922 The Meaning of Relativity, which collected four of Einstein’s 1921 Princeton lectures, although Edward O’Shea’s A Descriptive Catalog of W.B. Yeats’ Library does not record evidence of Yeats’s marking it. Nor does Yeats appear to have marked J. W. Dunne’s An Experiment with Time, which examines the possibility that humans’ perceptual faculties extend into the fourth dimension and regularly refers to the New Physics. Yeats’s comments in a 4 December 1931 letter to L.A.G. Strong [q.v.], however, reveal that he was wrestling with its content: |

“I did not mean my allusion to ‘right and left’ as a criticism of Dunne. I was merely suggesting an extension of his experiment. By ‘before and after’ I meant past and future, and these Dunne had investigated with his experiments, and by ‘right and left’ I meant the relationship in space, not in time, which I am most anxious that he or somebody else should investigate. I won’t go into the question now of the infinite observer, for I should have to look up Dunne again. I may perhaps write to you later about it. It happens to touch on a very difficult problem, one I have been a good bit bothered by. If I could know all the past and all the future and see it as a single instant I would still be conditioned, limited, by the form of that past and the form of that future, I would not be infinite. Perhaps you will tell me I misunderstood Dunne, for I am nothing of a mathematician[.]” (Letters, pp.787-88). |

‘The publication date for Dunne’s work - 1929 - excludes it from consideration as a source for Yeats’s preliminary exploration of the New Physics - although it is early enough to have been a possible influence on his revisions of A Vision. [...] |

The Descriptive Catalog [Edw. O’Shea, NY: Garland 1985], however, lists several likely sources for his initial attempts ‘to understand a little modern research into this matter.’ (CVA 175) The foremost of these is Lyndon Bolton’s An Introduction to the Theory of Relativity, published in 1921. [....] Despite this relatively low level of mathematics, Yeats clearly felt his own limited mathematical skills hindered his understanding of the material and states as much both in the above quoted letter to Strong and in a passage from the 1925 edition of A Vision under the heading ‘The Cones: Higher Dimensions’ [quotes Yeats, AV]: |

“One of the notes upon which I have based this book says that all existence within a cone has a larger number of dimensions than are known to us, and another identifies Creative Mind, Will, and Mask with our three dimensions, but Body of Fate with the unknown fourth, time externally perceived. |

‘Another source of Yeats’s inspiration regarding the New Physics, based on the type and amount of marginalia and his comments to Olivia Shakespear in letters dated 15 and 22 April 1926, is Alfred North Whitehead’s Science and the Modern World (Cambridge UP 1926). Like Dunn, Whitehead is too late to have had an impact on A Vision (1925). Whitehead’s work did, however, have an impact on Yeats’s thinking as he revised his system for republication in 1937. Surprisingly, given Yeats’s interests in examining history for parallels with his Historical Gyres and with placing people into their proper phase, the inspiration he received does not come primarily from the first half of the book, which reviews the history of science and mathematics and the men and women who advanced these fields. Instead, Yeats focuses on the sections that examine Relativity and Quantum Theory. |

A number of the marginal comments and strokes in Yeats’s copy of Science and the Modern World, recorded by O’Shea in his Descriptive Catalog, make direct reference to the system of A Vision. The foremost amongst these is the idea of Unity of Being. In Yeats’s system, Unity of Being refers to the balance between and integration of the portions of any being, represented by the Faculties and/or Principles. Yeats found parallels between these and the portion of Quantum Theory that require, in Whitehead’s words, that ‘you must take the life of the whole body during any portion of [examined time]’ (emphasis Yeats’s). In the margin next to this passage, Yeats wrote, ‘Unity of Being’ [Whitehead, p.170]. |

[Here quotes letter to Olivia Shakespeare:] ‘The work of Whitehead’s I have read is ‘Science in the Modern World’ and I have ordered his ‘Concept of Nature’ & another book of his. He thinks that nothing exists but ‘organisms,’ or minds - the ‘cones’ of my book - & that there is no such thing as an object ‘localized in space,’ except the minds, & that which we call phisical objects of all kinds are ‘aspects’ or ‘vistas’ of other ‘organisms’ - in my book the ‘Body of Fate’ of one being is but the ‘Creative Mind’ of another. What we call an object is a limit of perception. We create each others universe, & are influenced by even the most remote ‘organisms.’ It is as though we stood in the midst of space & saw upon all sides - above, below, right and left - the rays of stars - but that we suppose, through a limit placed upon our perceptions, that some stars were at our elbow, or even between our hands. He also uses the ‘Quantum Theory’ when speaking of minute organisms - molecules - in a way that suggests ‘antithetical’ & ‘primary,’ or rather if he applies it to the organisms we can compare with ourselves it would become that theory. I partly delight in him because of something autocratic in his mind. His packed logic, his way of saying just enough & no more, his difficult scornful lucidity seem to me the intellectual equivalent of my own imaginative richness of suggestion - certainly I am nothing if I have not these. (He is all ‘Spirit’ whereas I am all ‘Passionate Body.’). He is the opposite of Bertrand Russell who fills me with fury, by his plebean loquacity[.]’ (CL InteLex 4863, 22 April [1926]; cf. L713-14). |

[...] In his next letter to her, dated 15 April [1926], he writes: ‘… I stay in bed for breakfast & read Modern philosophy. I have found a very difficult but profound person Whitehead who seems to have reached my own conclusions about ultimate things. He has written down the game of chess & I like some Italian Prince have made the pages & the court ladies have it out on the lawn. Not that he would recognize his abstract triumph in my gay rabble[.]’ (CL InteLex 4858; cf. Letters, p.712). |

|

| For bibliographical details of Whitehead’s Science and the Modern World (1925), see under Notes - as infra. The text is available in full at at Project Gutenberg [online; accessed 01.12.2024]; also as numbered paragraphs at Open Edition - online, accessed 03.11.2024. |

| [ ] |

[ top ]

Patrick Dowdall, ‘“What Ish My Nation?: W.B. Yeats and the Formation of the National Consciousness’, in Vogelview [journal of Eric Voegel Soc.] (12 Nov. 2019): ‘The most significant intersection of the supernatural and nationalism is found in his endeavors to establish an Irish mystical order, which would have had a castle located on an island in Lough Key as a center for its members’ contemplation. In his Autobiographies, he describes his ten year effort to find a philosophy and create a ritual for the order.’ [...; Dowdall writes of poems in The Rose:] ‘“To Ireland in the Coming Days” is the final poem in a volume called The Rose, published in 1895. [Ftn.: [N]early all which had been published three years earlier in a volume entitled The Countess Cathleen and Various Legends and Lyrics.] The initial poem of the section is “To the Rose upon the Rood of Time” (VP; 100) in which Yeats introduces us to the themes of the volume and tells us that he will “sing of Eire and the ancient ways.” If we look at the poems that follow, we find that four deal with Celtic mythology themes, six others are based on various Irish legends or themes, one of which is in the form of a traditional Irish ballad, three focus on the rose symbol, and five involve other themes, including love songs to Maud Gonne. Looking at some of these poems gives us a sense of how Yeats expected his poetry to contribute towards that national consciousness.

[Cont.:] ‘The first of the Celtic poems is “Fergus and the Druid” (VP ;102), whose subject is the noted figure of the Ulster cycle who gave up the kingship to Conchubar, according to the Tain because of his love for the latter’s mother. Yeats chose not to follow those sources and influenced by Samuel Ferguson’s version of the story (perhaps another example of faulty memory) attributed Fergus’ abdication to his desire to being released from the burden of governing and “to learn the dreaming wisdom.” “A wild and foolish labourer is a king,” he concludes. The Yeatsian Fergus moves into the forest to become a hunter and a poet with druid-like powers - to take up a “bag of dreams.” [Ftn.: The Ferguson’s version of the legend is set forth in his poem, “The Abdication of Fergus MacRoy,” in Lays of the Western Gael, London: B[e]ll & Daldy, 1865, p.27.] He is an archetype of the persistent Yeatsian theme: rejection of the material for the spiritual in its various forms, and the poem prominently features the dream symbolism. The second Fergus poem, “Who Goes with Fergus?” (Variorum, p.125) describes the former king at the height of his powers in the new world that he aspired to when he abdicated. He “rules the brazen cars, / ... the shadows of the wood, / And the white breast of the dim sea / And all disheveled wandering stars.” For one who is brooding on “hopes and fears” and “love’s bitter mystery,” Fergus’ example of having thrusting off the burdens of the material should be followed is the Yeatsian message.

[Cont.:] ‘“Cuchulain’s Fight with the Sea” (Variorum, p.105) is the first of Yeats’s many poems and plays to deal with Cuchulain and retells the story of Cuchulain’s killing of his son in a battle near the waves in which each is unaware of the identity of his foe. The unwitting son has been sent, under Yeats’s version of the story, by his mother who is upset because Cuchulain has abandoned her; the son heroically is receptive to the mission because he does not want to unheroically “idle life away, a common herd.” Following his discovery of the identity of his vanquished foe, Cuchulain enters into a period of profound mourning, a state that concerns King Conchobar who fears that Cuchulain will rise and slay them all after three days. Conchobar instructs his druids to place magical spells upon the warrior, who upon awakening advances into the sea and “for four days warred he with the bitter tide/ And the waves flowed above Him and he died.” By including the death, which does not occur in the traditional sources, Yeats heightens the tragic nature of the encounter. (Dowdall, op. cit. - available online; accessed 28.10.2024.)

[ top ]

Avies Platt, ‘A Lazarus Beside Me’, in London Review of Books (27 Aug. 2015), pp.29-32: Platt met Yeats at a meeting of the Sex Education Society held in the Grafton Galleries, London, in 1937 - presided over by Norman Haire and addressed by the German endocrinologist Harry Benjamin speaking on the topic of rejuvenation. Avies was fascinated by Yeats on sight, and more so when she learnt his name after she offered to drive him to the ensuing party in her car (a battered Singer). He appeared to her to be ‘the most striking-looking man I had ever seen: tall, somewhat gaunt, aristocratic, very dignified: a strong, yet sensitive face, crowned by untidy locks of white hair: horn-rimmed glasses, through which shone strange, otherworldly eyes.’ In her memoir, she retails his own account of the Steinach operation: ‘It was Haire who had performed the operation and to understand what Yeats himself thought of the success of it one must have heard him testify with the vigour and emphasis with which he testified to me as we drove across London that night. “I regard it,” he said, “as one of the greatest events, if not the supreme event, of my life. It is impossible to describe what I experienced when I came round from the anaesthetic. It was like a sudden rush of puberty, yet coming at a time of life that made it intelligible: it was something now that one could understand. I felt life flowing into me. Before the operation, I could scarcely walk across the room without holding on to a chair. I was tortured by desire but could do nothing, or if I tried was prostrate with exhaustion. I had not written, at least anything of worth, for years. But now I was completely cured. I’ve been potent ever since. And above all I started writing again and with a zeal I had scarcely felt before, and in my own opinion what I have written since is some of the best work of my life.”’

Further: ‘It [the operation] was, in his own words, one of the greatest events, if not the supreme event, of his life, because by it he was enabled to attain heights he never would otherwise have attained and to finish his course in a way it would not otherwise have been finished. Whatever others may think, I am sure that to Yeats himself the operation was no isolated incident, no purely exciting episode, no mere physical or sexual rejuvenation, and indeed as Benjamin points out, we should speak rather of reactivation, revitalisation. Yeats would have been the first to say he was no longer the man of the Sargent portrait or the boy who had slept in Slish Wood. He was more, now, than these, for he had experienced a re-creation, a reassembling of himself of which lost youth was but a part. It was a re-creation sought and conditioned by his attitude to sex but it was intimately and inextricably bound up with that eternal search for truth and beauty, that life beyond life, to which his own was dedicated.’

Note: Platt identifies the energy of Yeats’s later writings with his acceptance of ‘sex as the fount from which life springs’ and explains his high estimate of the operation ‘because by it he was enabled to attain heights he never would otherwise have attained and to finish his course in a way it would not otherwise have been finished’. She first shared her information with Joseph Hone when he advertised in the TLS at the time of writing his life of Yeats, and later with Richard Ellmann whom Hone had passed her to. A serious illness prevented her from speaking further with Hone at the time. Her initial reason for attending the Haire session was her concern for her partner, an older man cited as “M.M.” and never identified. Haire expressed regret that that she had not availed of her meeting with Yeats to become his lover, eliciting her retort: ‘You may know everything about sex but your know nothing about love.’ (Available online; accessed 18 Aug. 2015.) he piece is dated ‘November 1946’ and appears to be a reprint if not a first publication of a writing of that date. I am grateful to Marion McDonald for bringing my attention to this article. BS 15.11.2024.]

| [ back ] | [ top ] | [ next ] |