| File 1 | File 2 | File 3 | File 4 | File 5 |

| File 6 | File 7 | File 8 | File 9 | File 10 |

| File 11 | File 12 | File 13 |

| General Index |

| John Middleton Murry (1922) to Harold Nicholson (1931) | |||

| John M. Murry Shane Leslie [Sir] C. C. Martindale C. Maitland |

Mary Colum Joseph M. Hone Stephen Gwynn Ernest Boyd |

Con Leventhal Edmund Gosse Wyndam Lewis Italo Svevo |

Seán O’Faoláin John Eglinton Frank O’Connor Harold Nicholson |

John Middleton Murry (review of Ulysses, 1922), ‘The cant phrase of judgment upon Mr. Joyce’s magnum opus has been launched by a French critic. “With this book”, says M. Valéry Larbaud, “Ireland makes a sensational re-entrance into high European literature.” Whether anyone, even M. Larbaud himself, knows what is meant by the last three words, we cannot tell. A phrase does not have to be intelligible in order to succeed, and we already hear echoes of this pronouncement. Ulysses somehow is European; everything else is not. Well, well. Ulysses is many things: it is very big, it is hard to read, difficult to procure, unlike any other book that has been written, extraordinarily interesting to those who have patience (and they need it), the work of an intensely serious man. But European? That, we should have thought, is the last epithet to apply to it. Indeed, in trying to define it, we return again and again, no matter by what road we set out, to the conception that it is non-European. [..; 195] Mr. Joyce [...] is an extreme individualists. He acknowledges no social morality, and he completely rejects the claim of social morality to determine what he shall, or shall not, write. He is the egocentric rebel in excelsis, the arch-esoteric. European! He is the man with the bomb who would blow what remains of Europe into the sky [...] just as Mr. Joyce is in rebellion against the social morality of civilisation, he is in rebellion against the lucidity and comprehensibility of civilised art [...] Still if we ask, Is Ulysses a reflection of life through an individual consciousness, there can be no doubt of the reply. It is. It is a reflection of life [196] through a singularly complex consciousness [...] One might almost say that all the thoughts and all the experiences of those beings [Bloom, Marion], real or imaginary, from their waking to their sleeping on a spring day in Dublin in 1904, are given by Mr. Joyce: and not only the conscious thoughts - they are very differently conscious - but the very fringes of sentience [...] This transcendental buffoonery, this sudden uprush of the vis comica into a world wherein the tragic incompatibility of the practical and the instinctive is embodied, is a very great achievement. It is the vital centre of Mr. Joyce’s book, and the intensity of life which it contains is sufficient to animate the whole of it.’ (In Nation & Athenæum [XXXI] ,22 April 1922, pp.124-45; rep. in Robert Deming, ed., James Joyce: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1970 [Vol. 1] pp.195-98; pp.195-96.)

[ top ]

Sir Shane Leslie [as ‘Domini Canis’], review of Ulysses (1922): ‘[...] In this work the spiritually offensive and the physically unclean are united. We speak advisedly when we say that though no formal condemnation has been pronounced, the Inquisition can only require its destruction or, at least, its removal from Catholic houses. Without grave reason or indeed the knowledge of the Ordinary no Catholic publicist can even afford to be possessed of a copy of this book, for in its reading lies not only the description but the commission of sin against the Holy Ghost. Having tasted and rejected the devilish drench, we most earnestly hope that this book be not only placed on the Index Expurgatorius, but that its reading and communication be made a reserved case. [...;’ here notes that Joyce has portrayed the real-life figure of Fr. Conmee.] ‘Nothing could be more ridiculous than the youthful dilettantes in Paris or London who profess knowledge and understanding of a work which is often mercifully obscure even to the Dublin-bred. [...] Reading a textbook and boiling it down into lists is no new device and depends for its success on the eliminating touch with which Mr. Joyce is most inartistically unendowed. In fact, the reader in struggling from oasis to oasis will find himself caught in a Sahara that is as dry as it is stinking. It is only when he varies his cataloguing with rare or new words that he is endurable, as of the Dublin vegetable market [...]’ Concludes that the general reader is unlikely to be effected by the corrupting influence of ‘this abomination of desolation’ containing ‘so much rotten caviare’, and portrays the author as ‘frustrated Titan [who] revolves and splutters hopelessly under the flood of his own vomit.’ Also speaks of ‘the very horrible dissection of a very horrible woman’s thought [Molly].’ (Dublin Review, Sept. 1922, pp.112-19; rep. in Robert Deming, ed., James Joyce: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul 1970 [Vol. 1], pp.200-03; also quoted in Cairns & Richards, Writing Ireland: Colonialism, Nationalism and Culture,Manchester UP 1988, p.134; also more briefly in Stan Gébler Davies, James Joyce: A Portrait of the Artist, London: Poynter-Davis 1975, p.246, with the remark the Review’s opinion scarcely mattered.) [For further extracts, see under Shane Leslie, infra.]

Sir Shane Leslie, review-article on Ulysses (Quarterly Review, 238, Oct. 1922): ‘[...] For while it contains some gruesome and realistic pictures of low life in Dublin, which would duly form part of the sociological history of the Irish capital, it also contains passages fantastically opposed to all ideas of good taste and morality.’ (p.206.) ‘To be fair of Ulysses no adequate meaning can be attached at first reading, and for this reason the book, which is an assault upon Divine Decency as well as on human intelligence, will fail of its purpose, if purpose it has to grip and corrupt either the reading public or the impressionable race of contemporary scribes.’ (p.207.) ‘We have only an Odyssey of sewer [...] here we shall not be far wrong if we describe Mr. Joyce’s work as litrary Bolshevism. It is experimental, anti-conventional, anti-Christian, chaotic, totally unmoral. it is no less likely to prove the entangling shroud of its author [...] the soul-destroying work of writing entire pages, which alienists might only attribute [207] to one cause’ [unnamed]. Leslie derogates the ‘practice of introducing the names of real people into circumstances of monstrous and ludicrous fiction’ (p.209); further speaks of a ‘mist of sexual analysis and psychic unravelment’ and a ‘gigantic effort to fool the world’ by means of ‘bamboozlement’ (p.210.) [Cont.]

Sir Shane Leslie, review-article on Ulysses (Quarterly Review, 238, Oct. 1922) - cont. Leslie accuses Joyce of ‘little care for the sacra of Catholic or Protestant Christianity’, equating it with ‘the lowest depths of Rabelaisian realism’ (p.209); repudiates a French critic’s [Valéry Larbaud] claim that Ulysses is ‘proof of Ireland’s re-entry into European literature’ (p.209; see infra). ‘English critics will be divided and remain in amicable squabbling disagreement. Irish writers, whose own language was legislatively and slowly destroyed by England, will cynically contemplate an attempted Clerkenwell explosion in the well-guarded, well-built classical prison of English literature. [...]’ (p.210; Deming, op. cit., 1970, pp.206-10.)

Cf. Desmond MacCarthy, ‘Affable Hawk’, in “Books in General” [column], New Statesman ([7 April] 1923) - expressing admiration for Joyce’s achievement in Ulysses but wondering if perhaps Joyce has set the novel on a dead-end: ‘It is an obscene book... but it contains more artistic dynamite than any book published for years. That dynamite is placed under the modern novel.’ [Quoted in Sam Slote, Catalogue Notes, Buffalo Univ. Library [SUNY] “Bloomsday” Centennial Exhibit, 2004 [online; accessed 31.12.2008]. Note: The review is available at New Statesman - online; published 16 June 2012 - accessed 05.04.2015.

Sir Shane Leslie: review-article on Ulysses (Quarterly Review, 238, Oct. 1922) - further to above: ‘[T]he book must remain impossible to read, and in general undesirable to quote. [...] Our own opinion is that a gigantic effort has been made to fool the world of readers and even the Pretorian guard of critics. [...] From any Christian point of view this book must be proclaimed anathema, simply because it tries to pour ridicule on the most sacred themes and characters in what has been the religion of Europe for nearly two thousand years. And this is the book which ignorant French critics hail as the proof of Ireland’s re-entry into European literature!’ (As above; quoted in Sam Slote, Catalogue Notes, Buffalo Univ. Library “Bloomsday” Centennial Exhibit, 2004 [online; accessed 31.12.2008]; also [in part] by Michael Groden, ‘The Complex Simplicity of Ulysses’, in James Joyce, ed. Sean Latham (Dublin & Portland: IAP 2010, p.107.)

[ top ]

C. C. Martindale, S.J. (‘Ulysses’, 1922), compares Joyce to the Futurist painters and accuses him of the same anti-formal ‘atrocities, in words instead of paint. He goes down to that level where seething insticnt is not yet illuminated by intellect, or only just enough to be not quite visible [...] Mr. Joyce gets as far down down as he can to this level of animality which exists, of course, as an ultimate in every man, and then, consciously and by art, tries to reproduce it. And this requires the most strong mental effort. For he has to hold together what yet must somehow remain incoherent; never to [204] forget what the conscious memory has never been in possession of; to put into the impressions of the evening all that the morning held but was never known to hold [...] to show us what essentially was never consciously know, still less remembered. Hence an angry sense of contradiction in the reader. Mr. Joyce is trying to think as if he were insane. [/.../] Mr. Joyce would therefore seem not only to have tried to achieve a psychological impossibility but to have tried to do so in what would, anyhow, have been the wrong medium. He would most nearly have succeeded by using music, and counterpoint. / However, we did, in reading, collect one impression: that is, that in calling his book, and in a sense his hero, Ulysses, Mr. Joyce meant to portray in him that “No Man” who yet is “Everyman”, ‘just because Mr. Joyce considers he has got down to the universal substratum in man which yet cannot be identified with any man in particular. We surmise, too, that there is a deal of Ulysses-symbolism running through the book; but we were not nearly interested enough to try to work it out. But what we object to is this: if that “ultimate”, that human Abyss, is to be seen at all, described at all, some light some intellectual energy, must have played upon it. But here it is most certainly not the Spirit of the Creator that has so played. What black fires may not the Ape of God light up? Into what insane caricatures of humanity may not the Unholy Ghost, plunging gustily upon animal instinct, fashion it? This book suggests an answer. At best the author’s eyes are like the slit eyes of Ibsen’s Trolls. They see, but they omit what is best worth seeing; they see, but they see all things crooked. Take a concrete instance: Mr. Joyce has, in this book too, the offensive habit of introducing real people by name. We know some of them. One such person (now dead, it is true) we knew well enough to see that Mr. Joyce, who describes him in no unfriendly way, yet cannot see. We absolve him of wilful calumny. [205] But we realise that he is at least more likely than not to have mis-seen not only one person, but whole places, like Dublin, or Clongowes; whole categories, like students; whole literatures, like the Irish, or the Latin. / Alas, then, that a man who can write such exquisite prose-music [...] should be at his most convincing in his chosen line when murmuring through half a hundred pages the dream-memories of an uneducated woman.’ (In Dublin Review, CLXXI, 1922, pp.273-76; rep. in Robert Deming, ed., James Joyce: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1970 [Vol. 1], pp.204-06.)

Cecil Maitland (‘Mr. Joyce and the Catholic Tradition’, August 1922): ‘[T]hough there is in this book enough fun to make the reputation of a dozen humorous writers, there is no hint of a conception of the human body as anything but dirty, of any pride of life, or of any nobility but that of a pride of intellect. This vision of human beings as walking drain-pipes, this focussing of life exclusively round the excremental and sexual mechanism, appears on the surface inexplicable in so profoundly imaginative an observant a student of humanity as Mr. Joyce. He has, in fact, outdone the psycho-analysts, who admit “sublimation”, and returned to the ecclesiasical view of man [...] No one who is acquainted with Catholic education in Catholic countries could fail to recognise the sourve of Mr. Joyce’s Weltanschauung. He sees the world as theologians showed it to him. His humour is the cloacal humour of the refectory; his contempt the priests’ denigration of the body, and his view of sex has the obscenity of a confessor’s manual, reinforced by the profound perception and consequent disgust of a great imaginative writer.’ (New Witness, XX, 4 Aug. 1922, pp.70-71; rep. in Robert Deming, ed., James Joyce: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1970 [Vol. 1], pp.272-73; p.273.)

Mary Colum (‘Confessions of James Joyce’, 1922): ‘[...] Such being the nature of the book, it is clear that the difficulty of [231] comprehending it will not be allowed to stand in the way by anybody who can get possession of it. Joyce has so many strange things to say that people would struggle to understand him, no matter in what form or tongue he wrote. Yet the difficulties in the way are very real; Ulysses is one of the most racial books ever written, and one of the most Catholic books ever written; this in spite of the fact that one would not be, surprised to hear that some official of the Irish Government or of the Church had ordered it to be publicly burned. It hardly seems possible that it can be really understood by anybody not brought up in the half-secret tradition of the heroism, tragedy, folly and anger of Irish nationalism, or unfamiliar with the philosophy, history and rubrics of the Roman Catholic Church; or by one who does not know Dublin and certain conspicuous Dubliners. The author himself takes no pains at all to make it easy of comprehension. Then, too, the book presupposes a knowledge of many literatures; a knowledge which for some reason, perhaps the cheapness of leisure, is not uncommon in Dublin, and, for whatever reason, perhaps the dearness of leisure, is rather uncommon in New York. In addition, it is almost an encyclopedia of odd bits and forms of knowledge; for the author has a mind of the most restless curiosity, and no sort of knowledge is alien to him. Ulysses is a kind of epic of Dublin. Never was a city so involved in the workings of any writer’s mind as Dublin is in Joyce’s; he can think only in terms of it. [...] There is little in the way of incident [...] The Walpurgis night scene (not called by that name) is too long and too incomprehensible; one feels that Joyce has here driven mind too far beyond the boundary-line that separates fantasy and grotesquerie from pure madness.’ [...] ‘He has achieved what comes pretty near to being a satire on all literature. He has written down a page of his country’s history.’

Further (Mary Colum, ‘Confessions of James Joyce’, 1922): ‘Some attempt is being made by admirers to absolve Joyce from accusations of obscentity in this book. Why attempt to absolve him? It is obscene, bawdy, corrupt. But it is doubtful that obscenity in literature every really corrupted anybody. The alarming thing about Ulysses is very different; it is that it shows the amazing inroads that science is making in literature. [.... &c.]’ ([Review-article on Ulysses], in Freeman, V, 123 (19 July 1922), pp.450-52; rep. in Robert Deming, ed., James Joyce: The Critical Heritage, London; Routledge & Kegan Paul 1970 [Vol. 1], pp.231-34.) [Note that Joyce tol Mary Colum this review was among those that pleased him most (see Deming, op. cit., p.231).]

Mary Colum - interview: ‘In Joyce’s study in his apartment at Square Robiac, he would have a bottle of white chianti on the table, a medley of books and notebooks, a gramaphone somewhere near: surrounded by such items, he and his helper set to work. The amount of reading done by his helpers was libarious, as he might have written himself, as were the notebooks filled with the results of their reading which generally boiled down to only a line or paragraph.’ (Quoted in Gordon Bowyer, James Joyce, p.351, citing Colum in E. H. Mikhail, ed., James Joyce: Interviews and Recollections, London: Wiedenfeld & Nicolson 1990, p.163.)

Note: Mary Colum memorialised a visit to Joyce in which she bearded him for his supposed antipathy to intellectual women when she taxes him with gulling people over the supposed Dujardin connection while denying an affinity with Freud and Jung [vide Ellmann, JJ] and was also the recorder of the following exchange: ‘When Joyce said, “I hate women who know anything”, Mary Colum replied, “No Joyce, you like them.”’ (See Life and the Dream, p.395; cited in Tapier, op. cit., supra, 1998, p.40.)

Our Friend James Joyce, by Mary and Padraic Colum (1959): ‘James Joyce writes as if it might be taken for granted that his readers know, not only the city he writes about, but its little shops and its little shows, the nicknames that have been given to its near-great, the cant phrases that have been used on the side streets.’ (p.142.)

[ top ]

Joseph M. Hone (‘A Letter from Ireland’, 1923): ‘We may have other literary exiles, but none of them provoke the same acute interest. [... T]here is nothing genial in Mr. Joyce’s comment. He may be detached from our local passions; but it is not a detachment born of English influences or of cosmopolitanism. His struggle for freedom had been fought before he left [297] Ireland; and the marks of the strugggle are in each of the books he has written [... /] Mr. Joyce’s books exhibit a type of young Irishman of the towns - mostly originating from the semi-anglicised farming or shopkeeping class of the cast and centre - a type which has been created largely by the modern legislation which provides Catholic democracy in Ireland with opportunities for an inexpensive university education. This young Irishman is now a dominating figure in the public life of Ireland; he was less important in Mr. Joyce’s day, but had already exhibited a certain amount of liveliness. Daniel O’Connell described him, before he had come to the towns and got an education, as smug, saucy, and venturous; and the portrait is still recognisable, though he was then only in the embryo stage of self-consciousness. As social documents, therefore, Mr. Joyce’s novels and stories are much more important than Synge’s plays and stories; for the later writer describes, intimately and realistically, a growing Ireland, not, as Synge did, an Ireland that is passing away with the Gaelic communities of Aran and Connemara. He writes of a side of life in which - ugly though his picture may be - there is the greatest spiritual energy, a side of Irish life of which our “Protestant” novelists, like Mr. Ervine and Mr. Birmingham, scarcely wot of except in its political manifestations. This young Irishman has, however, entered literature in a few other recent books besides those of Mr. Joyce - in the books, for example, of Mr. Daniel Corkery, a talented writer from Cork, whose Hounds of Banba, a collection of stories about the Volunteers, has been much admired. [...]. When I first read Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man it seemed to me that the book announced the passing of that literary Ireland in which everyone was well bred except a few politicians.’ [...]’ (London Mercury, V, January 1923, pp.306-08; rep. in Robert Deming, ed., James Joyce: The Critical Heritage, London; Routledge & Kegan Paul 1970 [Vol. 1], pp.297-99.)

Joseph M. Hone: ‘When I first read A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, it seemed to me that the book announced the passing of that literary Ireland in which everyone was well bred except a few politicians. For us in Ireland Mr. Joyce’s significance lies in this, that he is the first man of literary genius, expressing himself in perfect freedom, that Catholic Ireland has produced in modern times.’ (‘Memoir’; quoted in Peter Costello, James Joyce: The Years of Growth, London: Kyle Cathie 1992, p.278 [not in ‘Recollections ... &c.’, in Envoy 1951].)

[ top ]

Stephen Gwynn, ‘Modern Irish Literature’ (1923): ‘In considering modern Irish literature one has to face the fact that the first notable force to appear in it from the Catholic population has been Mr. Joyce. [...] if the current of feeling drives one author to present such a picture of priests without charity, women without [299] mercy, and drink-sodden, useless men, the same forces will surely push another into open defiance of the religion on which that life is presumed to rest. That is the revolt which you find in Mr. Joyce. I do not know that he detests the life of Dublin with the same intensity as Mr. [Brinsley] Macnamara [sic] loathes his valley [...] For Mr. Joyce, as I take it, Dublin is life, life is Dublin, and he, being alive, is bound to the body of this death. [...] I do not pretend to like Mr. Joyce’s work, and, admitting its power, it seems to me [...] that his preoccupation with images of nastiness borders on the insane. But the power of writing is astonishing. In Ulysses it comes to the full. [...] what gives value to Ulysses is passion: all through it runs the cry of a torutred soul. Mr. Joyce’s Stephen Dedalus is the Catholic by nature and tradition, who must revolt under the stress of an intellectual compulsion, to whom truth - the thing which he sees as true - speaks inexorably. Yet what he would shake off clings to his flesh like the poisoned shirt of Hercules. He wallows, it burns the more, but revolt persists. He can touch, taste and handle every abomination; only one thing is impossible, to profess a faith that he rejects. Ancient pieties hold him to it, ties of nearest life: his mother dying of cancer, dumbly prays of him to pray with her, and she dies without that solace; years pass, her thought, haunting him everywhere and always, only urges him to spit again on whatever she and her like thought holiest. It is revolt the more desperate because it sees no chance of deliverance; and against this fool, this Dedalus, with [300] the stored complex of his brain oversubtilised and overcharged by the very training of that scholastic philosophy from which he breaks away, Mr. Joyce sets his wise man Ulysses, the fortunate happy, whom life cannot injure, lacerate, or bruise, because he has no shame, who must enjoy, so full is his sensual development; who can enjoy, being without conscience [...] a renegade Jew, whose trading is touting advertisements, but whose subsistence comes through marrage: I need not be more precise [...].’ (In Manchester Guardian, 15 March 1923, pp.36-40; rep. in Irish Literature and Drama in the English Language, London: Nelson 1936, pp.192-202; and rep. in Robert Deming, ed., James Joyce: The Critical Heritage, London; Routledge & Kegan Paul 1970 [Vol. 1], pp.299-301.)

Stephen Gwynn, Irish Literature and Drama in the English Language (London: Nelson 1936), comments on Joyce’s relation to Irish history and language, introducing him in the context of Parnellite feuds, and calling his father as a ‘Parnellite organiser’. He quotes fully from the ending of “The Dead”, and also from the Christmas party quarrel over ‘my dead king’ in A Portrait. He also quotes Stephen’s thoughts on the language of the Dean of Studies, commenting: ‘This poignant cry of the disinherited runs all through Joyce’s writing. Nothing is left to the Irish Catholic; his country is a stranger’s even his language is what the stranger’s occupation has imposed [...] he derives from the new movement nothing more than an added sense of defeat [...] No inheritance but a spirit of revolt [...] But the revolt - so it looked to that period of squalid collapse - had produced nothing but a futile gesturing attitude. [...] his own father’s lifelong gesturing had effected nothing except to bring on his household the servitude of squalid poverty [...] religion [...] either complete submission or revolt [...] Irish Catholicism [...] singular narrowness / All these ties, gripping and coercing him, were drawn sharper by the hardest of all - the mother-tie.’ [195]. Gwynn returns to Joyce in the following chapter: ‘Joyce’s two main books, whatever else they may be, are the study of a diseased mind; and a great part of the disease is the inferiority complex, pride run mad. What is healthy in them, what gives them their peer, is the fight for freedom. But Joyce is exceptional in Irish literature, because the freedom at stake for him is freedom from Irish fetters, self-imposed by the race. He contends for the right of the individual soul to assert itself in its own fashion. Plunges into disgustfulness are no less [206] normal expressions of the nature he depicts than are mad efforts of a beast to escape bridle and saddle’ (pp.195, 206-07). See also his remark in regard to Mangan’s “The Nameless One” that ‘[t]hat soul is close of kin to Stephen Dedalus, in Joyce’s Ulysses’ (Chap. 6.)

[ top ]

Ernest A. Boyd, Ireland’s Literary Renaissance [rev. edn.] (London: Grant Richards 1922): ‘[A] French critic [Larbaud] has rashly declared that with them “Ireland makes a sensational re-entry into European literature.” Apart from its affecting and ingenuous belief in the myth of a “European” literature, this statement of M. Valéry Larbaud’s has the obvious defect of resting upon two false assumptions [...] In other words, to the Irish mind no lack of appreciation of James Joyce is involved by some slight consideration for the facts of Ireland’s literary and intellectual evolution, and the effort now being made to cut him off from the stream of which he is a tributary is singularly futile. The logical outcome of this doctrinaire zeal of the coterie is to leave this profoundly Irish genius in the possession of a prematurely cosmopolitan reputation, the unkind fate which has always overtaken writers isolated from the conditions of which they are a part, and presented to the world without any perspective. / Fortunately, the work of James Joyce stands to refute most of the theories for which it has furnished a pretext, notably the theory that it is an unanswerable challenge to the separate existence of Anglo-Irish literature. The fact is, no Irish writer is more Irish than Joyce; none shows more unmistakably the imprint of his race and traditions. The syllogism seems to be: J. M. Synge and James Stephens and W. B. Yeats are Irish, therefore James Joyce is not. Whereas the simple truth is that A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man is to the Irish novel what The Wanderings of Oisin was to Irish poetry and The Playboy of the Western World to Irish drama, the unique and significant work which lifts the genre out of the commonplace into the national literature.’ [302] ‘[...] Ulysses is simultaneously a masterpiece of realism, of documentation, and a most original dissection of the Irish mind in certain of its phases usually hitherto ignored, except for hints of George Moore. Dedalus and Bloom are two types of Dubliner such as were studies in Joyce’s first book of stories, remarkable pieces of national and human portraiture. At the same time they serve as the medium between the reader and the vie unanime of a whole community, whose existence is unrolled before their eyes, through which we see, and reaches our consciousness as it filters through their souls.’ [...; 304; cont.]

Ernest A. Boyd (Ireland’s Literary Renaissance,1923) - cont.: ‘Much has been written about the symbolic intent of this work, of its relation to the Odyssey. To which the plan of the three first and last chapters, with the twelve cantos of the adventures of Ulysses in the middle, is supposed to correspond. Irish criticism can barely be impressed by this aspect of a work which, in its meticulous detailed documentation of Dublin, rivals Zola in photographic realism. In its bewildering juxtaposition of the real and the imaginary, of the commonplace and the fantastic, Joyce’s work obviously declares its kinship with the Expressionists, with Walter Hasenclever or Georg Kaiser. / With Ulysses James Joyce has made a daring and valuable experiment, breaking new ground in English for the future development of prose narrative. But the “European” interest of the work must of necessity be largely technical, for the matter is as local as the form is universal. In fact, so local is it that many pages remind the Irish reader of Hail and Farewell, except that the allusions are to matters and personalities more obscure. To claim for this book a European significance simultaneously denied to J. M. Synge and James Stephens is to confess complete ignorance of its genesis, and to invest its content with a mysterious import which the actuality of references would seem to deny. While James Joyce is endowed with the wonderful fantastic imagination which conceived the fantasmagoria [sic] of the fifteenth chapter of Ulysses, a vision of a Dublin Brocken, whose scene is the underworld, he also has the defects and qualities of Naturalism, which prompts him to catalogue Dublin tramways, and to explain with the precision of a guide-book how the city obtains its water supply. In fine, Joyce is essentially a realist as Flaubert was, but, just as the author of Madame Bovary never was bound by the formula subsequently erected into the dogma of realism, the creator of Stephen Dedalus has escaped from the same bondage. Flaubert’s escape was by way of the Romanticism from which he started, Joyce’s is by way of Expressionism, to which he has advanced.’ [305]. (Boyd, Ireland’s Literary Renaissance [rev. edn.] 1923, pp.402-12: prev. [in part] as ‘The Expressionism of James Joyce’, in New York Tribune, 28 May 1923, p.29; rep. in Robert Deming, ed., James Joyce: The Critical Heritage, London; Routledge & Kegan Paul 1970 [Vol. 1], pp.301-05; pp.304-05; also quoted [in small part] in James Cahalan, The Irish Novel, 1988, p.130.) [For Larbaud’s response and Boyd’s answers, see under Boyd, infra.]

Ernest A. Boyd: ‘[...] Ulysses is simultaneously a masterpiece of realism, of documentation, and a most original dissection of the Irish mind in certain of its phaases usually hitherto ignored, except for hints of George Moore. Dedalus and Bloom are two types of Dubliner such as were studies in Joyce’s first book of stories, remarkable pieces of national and human portraiture. At the same time they serve as the medium between the reader and the vie unanime of a whole community, whose existence is unrolled before their eyes, through which we see, and reaches our consciousness as it filters through their souls. [...; 304] Much has been written about the symbolic intent[ion] of this work, of its relation to the Odyssey. To which the plan of the three first and last chapters, with the twelve cantos of the adventures of Ulysses in the middle, is supposed to correspond. Irish criticism can bardly be impressed by this aspect of a work which, in its meticulous detailed documentation of Dublin, rivals Zola in photographic realism. In its bewildering juxtaposition of the real and the imaginary, of the commonplace and the fantastic, Joyce’s work obviously declares its kinship with the Expressionists, with Walter Hasenclever or Georg Kaiser. / To claim for this book a European significance simultaneously denied to J. M. Synge and James Stephens is to confess complete ignorance of its genesis, and to invest its content with a mysterious import which the actuality of references would seem to deny. While James Joyce is endowed with the wonderful fantastic imagination which conceived the fantasmagoria [sic] of the fifteenth chapters of Ulysses, a vision of a Dublin Brocken, whose scene is the underworld, he also has the defects and qualities of Naturalism, which prompts him to catalogue Dublin tramways, and to explain with the precision of a guide-book how the city obtains its water supply. In fine, Joyce is essentially a realist as Flaubert was, but, just as the author of Madame Bovary never was bound by the formula subsequently erected into the dogma of realism, the creator of Stephen Dedalus has escaped from the same bondage. Flaubert’s escape was by way of the Romanticism from which he started, Joyce’s is by way of Expressionism, to which he has advanced.’ (Ireland’s Literary Renaissance, rev. edn., 1923, pp.402-12; prev. published [in part] as ‘The expressionist of James Joyce’, in New York Tribune, 28 May 1922, p.29; rep. in Deming, op. cit., 1971, pp.301-05; p.304-05.) [See Boyd, Ireland’s Literary Renaissance [1916]; extended edn. (1922) - at Internet Archive - online.]

Ernest A. Boyd, ‘Joyce and the New Irish Writers’, 1934: ‘Outside Ireland itself, this quintessentially Irish and local study of Dublin life as evoked somewhat extravagant enthusiasm and highly exaggerated claims for its importance. The distinguished French critic Valéry Larbaud [...] pitched the note when he declared that, with Ulysses, Ireland had made her re-entry into European literature. it is true that Mr. Joyce has made a daring and often valuable technical experiment, breaking new ground in English for the development of narrative prose [... b]ut the “European” interest of the work must of necessity be limited to its form, for its content is so local and intrinsically insignificant that few who are unfamiliar with the city of Dublin thirty years ago can possible grasp its allusions and enter into its spirit.’ [622] ‘To claim for this book a European significance denied to W. B. Yeats, J. M. Synge, or James Stephens is to ignore its genesis in favour of mere technique, and to invest its content with mysterious import which the actuality of the references would seem to deny. [...’; &c.] (In Current History, XXXIX, 1934, pp.699-704; rep. in Robert Deming, ed., James Joyce: The Critical Heritage, London; Routledge & Kegan Paul 1970 [Vol. 2], 622-23.)

[ top ]

Con Leventhal (as Laurence K. Emery [pseud.]), ‘The Ulysses of Mr. James Joyce’, in Klaxon (Winter 1923) [sole issue]: ‘There is in all his work a cold objectivity. He has an uncanny keenness of perception which he does not let his ego influence. This perception he must have applied to himself, and he can synthesise a character from details observed in his own person.’ (p.14); ‘the variegated fabric of Ulysses’ (p.15); one might argue [...] that Ulysses [like the Bible] is the work of many hands, where it not for the fact that in the seeming medley of chapters and styles there is a form as rigid as that of a sonnet [...] the Homeric hero [...] There is a scene in the national Library where Joyce, now clad in the garb of George Moore (I do not know whether it is intentional or not) makes the well-known librarians, whom he mentions by name, and AE discuss a curious theory of the influence of Shakespeare of his wife, Anne Hathaway. [...] [‘Cyclops’] written in the manner of a lower-middle class Dubliner [...] Ulysses is essentially a book for the male. It is impossible for a woman to stomach the egregious grossness. Through the book one hears the coarse oaths and rude jests of the corner-boy and the subtle salaciousness of the cultured. There is a tradition of these things. And as the oriental shuts his women from contact with the world with a yashmak and a harem, so we have cut off our womenfolk from our smoking-room hinterlands. It is not woman but man who has a secret, and Mr. Joyce is guilty of a breach of the male freemasonry in publishing the signs by which one man recognises a healthy living brother. [...] Mr. Joyce doesn’t trouble to invent one yarn. He uses those actually current in the Medical School of his day and quotes from the privately printed manuscripts of a brilliant surgeon, whom he disguises (for the nonce) with a fictitious name, stories and indecencies pickled in Gallic salt. We know the stories, and are tickled by the memories of male [?sprees] where we first heard them, horror-stricken the while lest our female friends see in callous print our eternal wild oats tendencies. I am conscious, however, that there are some women sufficiently masculine in temperament who can read Ulysses without any risk of disturbing their normal metabolism.’ [...] ‘a human book, filled with pity as with the sexual instinct, and the latter in no greater proportion and of no greater importance in the book than any of the other fundamental human attributes.’ (p.20; End). [For full text of this article, see RICORSO Library, “Criticism > Major Authors / Joyce”, via index or direct.]

Edmund Gosse (Letter to Louis Gillet, 7 June 1924): ‘I have a difficulty in describing to you, in writing, the character of Mr. Joyce’s notoreity [...] it is partly political; it is partly a perfectly cynical appeal to sheer indecency. He is of course not entirely without talent, be he is a literary charlatan of the exremist order. His principal book, Ulysses, has no parallel that I know of in French. It is an anarchical production, infamous in taste, in style, in everything / Mr. Joyce is unable to publish or sell his books in England, on account of their obscenity. He therefore issues a “private” edition in Paris, and charges a huge price for each copy. he is the perfect type of the Irish fumiste, a hater of England, more than suspected of partiality to Germany, where he lived before the war (and at Zürich during the War). / There are no English critics of weight or judgement who consider Mr. Joyce an author of any importance [...]’ (Quoted in Richard Ellmann, James Joyce, 1965 Edn., p.542, ftn.; rep. in Robert Deming, ed., James Joyce: The Critical Heritage, London; Routledge & Kegan Paul 1970 [Vol. 1], p.313.)

Wyndam Lewis (‘Analysis of the Mind of James Joyce’, in Time and Western Man, [Sept.] 1927): ‘[Ulysses] lands the reader inside] an Aladdin’s cave of incredible bric-à-brac in which a dense mass of dead stuff is collected [from 1901 toothpaste, a bar or two of sweet Rosie O’Grady, to pre-nordic architecture. An immense nature-morte is the result. This ensues from the method of confining the reader in] a circumscribed psychological space into which several encyclopaedias have been emptied]. It is a suffocating, moetic expanse of objects, all of them lifeless, the sewage of a past twenty years old, all neatly arranged in a meticulous sequence [...] It is the voluminous curtain that fell, belated (with the alarming momentum of a ton or two of personally organised rubbish), upon the Victorian scene. So rich was it delivery, its pent-up out-pouring so vehement, that it will remain, eternally cathartic, the record of diarrhoea [Time, p.109; quoted at Antwerp JJ Centre - online; accessed 05.04.2015.]. No one who looks at it will every want to look behind it. It is the sardonic catafalaque of the Victorian world.’ (Quoted in Hugh Kenner, Dublin’s Joyce, Chatto & Windus 1955, p.363; Kenner calls this ‘the most brilliant misreading in modern literature’, p.392.)

Further: ‘[Ulysses] will remain, eternally cathartic, a monument like a record diarrhoea. [...] He collected like a cistern in his youth the last stagnant pumpings of Victorian Anglo-Irish life. This he held steadfastly intact for fifteen years or more - then when he was ripe, as it were, he discharged it, in a dense mass, to his eternal glory. That was Ulysses.’ (Q.p.; given on Peter Chrisp Blogspot - online; accessed 06.04.2015.)

Viz., [T]here is not very much reflection going on at any time inside the head of Mr. James Joyce. That is indeed the characteristic conditoin of the craftsman, pure and simple [...] He is become so much a writing-specialist that it matters very little to him what he writes, or what idea or worldview he expresses [...] Ulysses is like a gigantic victorian quilt or antimacassar [...] it will remains, eternally cathartic, a momument like a record diarrhoea [...] It is the craftsman in Joyce that is progressive; but the man has not moved since his early days in Dublin. He is on that side of a “young man” in some way embalmed. His technical adventures do not, apparently, stimulate him to think. [...] Proust returned to the temps perdu. Joyce never left it. He discharged it as freshly as though the time he wrote about were still present, because it was his present. (Time and Western Man, Santa Rosa, Black Sparrow 1993), pp.88-91. Here p.43.

—Quoted in Douglas Mao, ‘Arcadian Ithaca’, in Maurizia Boscagli & Enda Duffy, eds., James Joyce and Magical Urbanism (Amsterdam: Rodopi 2011), [30];p.43. Wyndam Lewis (‘Analysis of the Mind of James Joyce’, in Time and Western Man, 1927) - cont. [on Stephen Dedalus]: ‘He is the really wooden figure. He is “the poet” to an uncomfortable degree, a dismal, a ridiculous, even a pulverising degree. His movements in the Martello-tower, his theatrical “bitterness”, his [363] cheerless, priggish stateliness, his gazings into the blue distance, his Irish Accent, his exquisite sensitiveness, his “pride” that is so crude as to be almost indecent, the incredible slowness with which he gets about from place to place, up the stairs, down the stairs, like a funereal stag-king; the time required for him to move his neck, how he raises his hand, passes it over his aching eyes, or his damp brow, even more wearily drops it, closes his dismal little shutters against his rollicking Irish-type [sic] of friend (in his capacity of a type-poet), and remains sententiously on secluded, shut up on his own personal Martello-tower - a Martello-tower within a Martello-tower - until he consents to issue out, tempted by the opportunity of making a “bitter” - a very “bitter” - jest, to show up against the ideally idiotic background provided by Haines [...].’ (Quoted in Kenner, op. cit., pp.363-64.)

Further [Wyndham Lewis]: ‘Joyce is the poet of the shabby-genteel, impoverished intellectualism of Dublin. His world is the small middle-class one, decorated with a little futile “culture”, of the supper and dance-party in The Dead. Wilde, more brilliantly situated, was an extremely metropolitan personage, a man of the great social work, a great lion of the London drawing-room. Joyce is steeped in the sadness and the shabbiness of the pathetic gentility of the upper shopkeeping class, slumbering at the bottom of a neglected province; never far, in its snobbishly circumscribed despair, from the pawn-shop and the “pub”’. (Q.p.; given on Peter Chrisp Blogspot - online; accessed 06.04.2015.)

Wyndam Lewis (Time and Western Man, 1927): ‘[Although] steeped in the sadness and the pathetic gentility of the upper shopkeeping classes, slumbering at the bottom of a neglected province [Joyce is] by no means without the personal touch. [...] Joyce and Yeats are the prose and poetry respectively of the Ireland that culminated in the Rebellion [of 1916 ...] There was an artificial, pseudo-historical air about the Rebellion, as there was inevitably about the movement of “celtic” revival; it seemed to have been forced and vamped up long after its poignant occasion had passed.’ (p.93, 94; quoted in Emer Nolan, James Joyce and Irish Nationalism, Routledge 1995, pp.11-12.)

Further [Wyndham Lewis: ‘So from the start the answer of Joyce to the militant nationalist was plain enough. And he showed himself in that a very shrewd realist indeed, beset as Irishmen have been for so long with every Romantic temptation, always being invited by this interested party or that, to jump back into “history”. So Joyce is neither of the militant “patriot type”, nor yet a historical romancer. In spite of that he is very “irish”. He is ready enough, as a literary artist, to stand for Ireland, and has wrapped himself up in a gigantic cocoon of local colour in Ulysses [...] Although entertaining the most studied contempt for his [11] compatriots - individually and in the mass - whom he did not regard at all as exceptionally brilliant and sympathetic creatures (in a green historical costume, with a fairy hovering near), but as average human cattle with an irish accent instead of a scotch or a welsh, it will yet be insisted on that his irishness is an important feature of his talent; and he certainly does exploit his irishness and theirs [...] / So Englishmen and Frenchmen who are inclined to virulent “nationalism” or disposed to sentiment where local colour is concerned, will admire Joyce for his alleged identity with what he detached himself from and even repudiated, when it took the militant, Sinn Féin form. And Joyce, like a shrewd sensible man, will no doubt encourage them.’ (pp.94-95; quoted in Nolan, op. cit., 1995, p.13; spelling lower-case “irish” sic in Lewis.)

Italo Svevo [Ettore Schmitz], ‘James Joyce’ (Lecture, Milan 1927): ‘[...] He is twice a rebel, against England and against Ireland. He hates England and would like to transform Ireland. Yet he belongs so much to England that like a great many of his Irish predecessors he will fill pages of English literary history and not the least splendid ones; and he is so Irish that the English have no love for him. They are out of sympathy with him, and there is no doubt that his success could never have been achieved in England if France and some literary Americans had not imposed it [...]’ Svevo concludes: ‘Joyce’s works, therefore, cannot be considered a triumph of psycho-analysis, but I am convinced that they can be the subject of its study. They are nothing but a piece of life, of great importance because it has been brought to light not deformed by any pedantic science but vigorously hewn with quickening inspiration. [.... &c.]’ (Printed in Il Convegno, Jan. 1938, pp.135-38; enl. & trans. by Stanislaus Joyce as James Joyce, 1950 [rep. 1967], 90pp.; rep. in Robert Deming, ed., James Joyce: The Critical Heritage, London; Routledge & Kegan Paul 1970 [Vol. 1], pp.354-56.)

[ top ]

Sean O’Faoláin, ‘Style and the Limitations of Speech’ (Sept. 1928): ‘Here lies the condemnation of such language as Joyce’s. It is not merely ahistoric - not merely the shadow of an animal that never was, the outline of a tree that never grew, for even then we might trace it to some basic reality distorted and confused - but it comes from nowhere, goes nowhere, is not part of life at all. It has one reality only - the reality of the round and round of children’s scrawls in their first copybooks, zany circles of nothing. It may be that Joyce wishes these meaningless scrawls to have a place in his design and if so nobody will grudge him his will of them. But we cannot be expected to understand them as language for they are as near nothing as anything can be on this earth. Yet who cannot sympathise with this rebellion? It would seem that Joyce does not realise, however, that in language we are countering one of those primal impositions that give to life its inexorable character: he must see that in language there is an individuality which we must counter at every step, much as an actor must counter his own character to express ideas at variance with it. But a man who has had the great courage to accept so many of life’s inexorable laws does unwisely to push a puppet in the actor’s place; that offers us no release. It is a puppet without as much as the shape of a human being, and suggests the idea of a human organism for but one reason, that it has usurped the place of one. [...]’ (Criterion, Sept. 1928, pp.67-87 [intermitt.]; prev. as ‘The Cruelty and Beauty of Words’, in Virginia Quarterly Review, IV, 2, April 1928, pp.208-25 [intermitt.]; rep. in Robert Deming, ed., James Joyce: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul 1970 [Vol. 2], p.391.

Sean O’Faoláin, review of Finnegans Wake, in Irish Statemen (5 Jan. 1929; rep. in Robert Deming, James Joyce: The Critical Heritage, Vol. 2, 1970, pp.396-97): ‘If Joyce had only written the entire book as he did the final paragraph, what a marvellous book it would be! If only he had accepted the inexorable truth that language is a very limited and imperfect medium - as he has with unparalleled courage accepted so many [397] of the other inexorable facts of life! But he is here very much of his race... If there ever was an adventure which was a revolt against the despotism of fact this little book is one, and as such, if not as literature, it is priceless ...’ (Quoted in Gerry Smyth, Decolonisation and Criticism: The Construction of Irish Literature,London: Pluto Press 1998, [p.85].)

Sean O’Faoláin, ‘Anna Livia Plurabelle’ (Jan. 1929): ‘[...] Joyce has gambled on an intellectual theory and invented a technique where the controls are supposed to be more rigid, and, it follows, the power of the artist all the greater: but is it so? [...] The fact is that the more elusive his phrases are the more we find that our responses are liable to be a medley of sensuous images [...] the sensuous response[s] of the mind to his new language are sometimes very delicate and pleasing, sometimes obscene, sometimes merely dull - well, so is reality - but most frequently, because this is language, and language has a biologically inexorable thirst for assocations, they are empty of content. [.../] Joyce’s medium strikes at the inevitable basis of language, universal intelligibility, and though the sympathetic may burk at the word “universal”, or the word “intelligible”, it must be acknowledged that there is very little difference between issuing a tiny booklet of some nine thousand words in a limited edition at a prohibitive price and not issuing it at all. / Yet no genuine student of literature can dare to be unfamiliar with it: it is one of the most interesting and pathetic literary adventures I know, pathetic chiefly because of its partial success: for even the most sympathetic and imaginative will have smiled wanly several times as they read and laughed in despair long before the end.’ [...; 397.]

Further, ‘If every there was an adventure which was a revolt against the despotism of fact this little book is one, and as such, if not as literature, it is priceless.’ [398] (Irish Statesman, 5 Jan. 1929, pp.354-55; rep. as ‘Almost Music’, in Hound and Horn, Jan.-March 1929, pp.178-90; rep. in Robert Deming, ed., James Joyce: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul 1970 [Vol. 2], pp.396-98.) The letter summoned a reply from Eugène Jolas (Irish Statesman, Feb. 1929) which was in turn answered by O’Faolain on 2 March 1929 asking if ‘Mr. Joyce, M. Jolas, and the other innovators he names have really thought the matter out clearly’ and ending: ‘nothing but his [Joyce’s] great genius has saved him from utter failure [...]’; Deming, op. cit., p.400.)

Sean O’Faoláin revises his opinion of ALP, ‘Letter to the Editor’, in Criterion (Oct. 1930), p.147 - refers to prev. article in Criterion (Sept. 1928): ‘[...] I did not do complete justice to Mr. Joyce’s new porse, and with your permission I should like to add a further word ... I do not think that there is anything in that essay which I do not still believe, bt it did not go far enough in its appreciation of the merits that do lie in Mr. Joyce’s language. It becomes clear to me that a kind of distinciton once properly made between prose nad poetry is passing away [...] This prose that conveys its ‘meaning’ vaguely and unprecisely, by its style rather than its words, has its delights, as music has its own particular delights proper to itself, and I have wished to say that for these half-congey, or not even half-conveyed suggestions of ‘meaning’ Mr. Joyce’s prose can be tantalizingly delightful, a prose written by a poet who missed the tide, and which can be entirely charming if approached as prose from which an explicit or intellectual communication was never intenede.d In my article and elsewhere, i suggested that such prose is, as it were, orally deficient - being almost wholly sensous - but that question I do not wish to re-open here. rep. in Deming, op. cit., Vol. 2, p.413.)

Seán O’Faoláin, making a comparison between Joyce and Gogarty in the context of his account of the ethos of Presentation College, Cork: ‘How few escaped, could escape, or wished to escape that trap! If James Joyce had had half an ounce of social conscience, of Stendhal’s or Balzac’s awareness of the molding [sic] power of the cash-nexus, he would have made this clear in his Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. He had it most near to clear when he contrasted Daedalus, the poor rebel - but not against both the Empire and the Church - with Buck Mulligan, who set out to conform. My school produced some rebels but not many; it produced conformists by the ton.’ (Vive Moi, 1993 Edn., Sinclair-Stevenson, p.92.)

Seán O’Faoláin, review of Joyce’s Politics by Dominic Magnanielli, in London Review of Books (Oct. 1980): ‘[...] It is all a matter of definition. If the sort of politics I have been referring to did interest Joyce, then we at once understand their relevance to the man’s bent, character, genius, spirit - call it what one wills - that is, we can have at least some idea of the magical process whereby this sort of “politics” enriched his Human Comedy in the hilarious Cyclops chapter of Ulysses, with its brawling but never boring comic character called “The Citizen”, and how they deepened the Human Tragedy of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man with that painful scene where the family battles passionately over Parnell. But if that possessive apostrophe in the book’s title means that Joyce was nourished in his work by knowing le dessous des cartes of politics as the science of governing a country or managing a community, then even his most devoted and admiring readers (among whom I ardently reckon myself) are going to find it hard to reconcile this sort of social-minded, institution-oriented writer with the impression most of us have gathered from his life and writings of a passionate, poetic loner, virtually an élitist, withdrawn, a sceptical, ironical exile who never joined anything larger than a dinner party in a first-class Parisian restaurant. / So then, it is not only a question of the definition of the word ‘politics’ but a redefinition of the writer and the man. Perhaps Dominic Manganiello has demonstrated this kind of formative interplay in Joyce’s mind between the art of government and the art of literature? Perhaps he has shown us how irredeemably different A Portrait or Ulysses would have been without their author’s study of, say, Irredentism, Nationalism, Socialism, Anarchism, Bakunin, Ferrero, Marx? The idea is so exciting that I decide to take a refresher look at A Portrait. [...]’

O’Faolain goes on to suggest that Magnanielli overplays the political side of Joyce’s early life, illustrating his criticism by citing the remark that the young Joyce at Clongowes engages in a ‘meditation’ on the 18th century politics of the United Irishmen - whereas Joyce simply writes of the fever-stricken Stephen (aged 6 to 9) that ‘wondered from what window Hamilton Rowan had thrown his hat on the haha’ - remarking ‘[t]he scholar in his understandable eagerness not to miss a trick has made much ado about little or nothing. The example is, indeed, trivial, but it illustrates a danger that too often mars an over-conscientious book.’ (See full-text copy in RICORSO > Library > Criticism > “Major Authors”, via index, or direct.)

[ top ]

John Eglinton, “Irish Letter”, in Dial (May 1929): ‘[...] Joyce is, I should think, the idol of a good many of the young men of the new Ireland. Is Joyce then what my ethnological friend would have called a “key-personality”? I am inclined to think that he may so one day be considered, and so to a certain extent even accounted for. He has, apparently, abjured Ireland; the subjects of all his ridicule are Irish; moreover, it is improbable that when the new censorship begins to operate, the mind of the youth will have any but furtive opportunities to form itself upon Joyce’s writings. Joyce is, none the less, in several respects a champion spirit in the new national situation. In him, for the first time, the mind of Catholic Ireland triumphs over the Anglic[an]ism of the English language, and expatiates freely in the element of a universal language: an important achievement, for what has driven Catholic Ireland back upon the Irish language is the ascendancy in the English language of English literature, which, as a Catholic clergyman once truly asserted, is “saturated with Protestantism.” In Joyce, perhaps for the first time in an Irish writer, there is no faintest trace of Protestantism: that is, of the English spirit. [...] we are obliged to admit that in Joyce literature has reached for the first time in Ireland a complete emancipation from Anglo-Saxon ideals.’ Remarks on the Irishness of Joyce’s ‘almost pedantic preoccupation with language’ and calls this a feature of his mind that puts the ‘foreign critic [...] at a disadvantage compared with one who is acquainted with Joyce’s race and upbringing’.

Further: ‘Critics of Joyce appear to me to ignore too much his peculiar origins, and it would be advantageous for the critical comprehension of Joyce generally and for Joyce himself - as it is for every important writer - that a country should be found for him. [...]’ (pp.41-20; rep. in Robert Deming, ed., James Joyce: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul 1970 [Vol. 2], pp.456, 459.) Note: see also his earlier “Dublin Letter”, in Dial (June 1922), in which he admits that he does not fully understand Ulysses, even the parts in which his character appears. (Quoted in Sam Slote, Catalogue Notes, Buffalo Univ. Library “Bloomsday” Centennial Exhibit, 2004 [online; 31.12.2008].)

John Eglinton, Life and Letters (1932): ‘When Joyce produced Ulysses he had shot his bolt. Let us put it without any invidiousness. He is a man of one book, as perhaps the ideal author always is. Besides, he is not specially interested in “literature”, not, at all events, as a well-wisher. [...] As for Joyce, his interest is in language and the mystery of words. He appears, at all events, to have done with “literature”, and we leave him with the plea for literature that it exists mainly to confer upon mankind a deeper and more general insight and corresponding powers of expression. Language is only ready to become the instrument of the modern mind when its development is complete, and it is when words are invested with all kinds of associations that they are the more or less adequate vehicles of thought and knowledge. And after “literature”, perhaps, comes something else. [...]’. (‘The Beginning of Joyce’, in Life and Letters, VIII, Dec. 1932, pp.400-14; rep. in Irish Literary Portraits, 1935, pp.131-52; rep. in Robert Deming, ed., James Joyce: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul 1970 [Vol. 2], pp.577-79.)

John Eglinton, Irish Literary Portraits (Macmillan 1935): ‘In the interview of the much enduring Stephen with the officials of the NL the present writer experiences a twinge of recollection of things actually said.” (Quoted in Stephen Gwynn, Irish Lit. and Drama, 1936, p. 199.)

‘George Moore used to talk with envy of those English writers who could use whole language [?the whole of the language]; and I really think that Joyce must be added to Moore’s examples of this power - Shakespeare, Whitman, Kipling. This language found itself constrained by its new master to perform tasks to which it was unaccustomed in the service of pure literature; and, against the grain, it was forced to reproduce Joyce’s fantasies in all kinds of juxtapositions, neologisms, amalgamations, truncations, words that are only found scrawled up in public lavatories, obsolete words, words in limbo or in the womb of time. It assumed every intonation and locution of Dublin, Glasgow, New York, Johannesburg. Like a devil taking pleasure in forcing a virgin to speak obscenely, so Joyce rejoiced darking in causing the language of Milton and Wordsworth to utter all but unimaginable filth and treason.’ —‘The Beginning of Joyce’, in Irish Literary Portraits, Macmillan 1935, p.145.

[...] Such is Joyce’s Celtic revenge, and it must be owned that he has succeeded in making logic and rhetoric less sure of themselves among our younger writers. As an innovator in the art of fiction I conceive him to be less formidable. Mankind has never failed to recognise a good story-teller, and never will. They say that Joyce, when he is in good humour among his disciples, can be induced to allow them to examine a key to the elaborate symbolism of the different episodes, all pointing inward to a central mystery, undivulged, I fancy. Ulysses, in fact, is a mock-heroic, and at the heart of it is that which lies at the heart of all mockery, an awful inner void. Ibid., p.146;

Further: ‘The conception of the Irish Jew, Leopold Bloom, within whose mind we move through a day of Dublin life, is somewhat of a puzzle. Buck Mulligan we know, and the various minor characters; and in the interview of the much-enduring Stephen with the officials of the National Library, the present writer experiences a twinge of recollection of things actually said. But Bloom, if he be a real character, belongs to a province of Joyce’s experience of which I have no knowledge. He is, I suppose, the jumble of ordinary human consciousness in the city, in any city, with which the author’s experience of men and cities had deepened his familiarity: a slowly progressing host of instincts, appetites, adaptations, questions, curiosities, held at short tether by ignorance and vulgarity; and the rapid notation which I conceive Joyce to have discovered originally in his diary served admirably [148] well to record these mental or psychic processes. Bloom’s mind is the mind of the crowd, swayed by every vicissitude, but he is distinguished through race-endowment by a detachment from the special crowd-consciousness of the Irish, while his familiarity with the latter makes him the fitting instrument of the author’s encyclopedic humour. Bloom, therefore, is an impersonation rather than a type: not a character, for a character manifests itself in action, and in Ulysses there is no action. There is only the rescue of Stephen from a row in a brothel, in which some have discovered a symbolism which might have appealed to G. F. Watts, the Delivery of Art by Science and Common Sense. But the humour is vast and genial. There are incomparable flights in Ulysses: the debate, for instance, in the Maternity Hospital on the mystery of birth; and above all, I think, the scene near the end of the book in the cabmen’s shelter, kept by none other than Skin-the-Goat, the famous jarvey of the Phoenix Park murders. Here the author proves himself one of the world’s great humorists. The humour as always is pitiless, but where we laugh we love, and after his portrait of the sailor in this chapter I reckon Joyce after all a lover of men.

‘When Joyce produced Ulysses he had shot his bolt. Let us put it without any invidiousness. He is a [149] man of one book, as perhaps the ideal author always is. Besides, he is not specially interested in “literature”, not at all events as a well-wisher. [...H]is interest is in language and the mystery of words. He appears at all events to have done with ‘literature’. and we leave him with the plea for literature that it exists mainly to confer upon mankind a deeper and more general insight and corresponding powers of expression.’ (Ibid., pp.148-49.)Eglinton’s Irish Literary Portraits is available at Internet Archive - online; accessed 13.03.2022. Note: Fran O’Rourke quotes Eglinton [William Patrick Magee] as referring to Joyce as ‘one of a group of liviely and eager-minded young men at University College [who were through their interest] in everything new in literature and philosophy far surpassed the students of Trinity College.’ (Irish Literary Portraits, 1935, p.132; O’Rourke, Joyce, Aristotle, and Aquinas [Florida James Joyce Ser.], Florida UP 2022, p.38.)

[ top ]

Frank O’Connor (Irish Statesman, April 1930): ‘Mr. Joyce’s reputation, such as it is, resets upon two books, the Portrait [... &c.] and Ulysses. In the two other books that preceded these he was obviously handing material which he could not work; he was neither a great romantic poet nor a great realistic story-teller, and his poems and stories were excellent only in their sensitiveness to form and style. / In the two biographical fantasies that followed, Ireland found its greatest artist. [...] In his latest work, reviled by friend and foe alike, Joyoce has carried those obsessions [viz., form and style] further, but the step is as big as that between [515] the Portrait and Ulysses; it is Joyce of the third period, and the greatest of Irish artists has sailed off into a world where the atmosphere - for most normal lungs - is so rare that it is scarce liveable-in. Nobody quite understands the form; nobody in Europe is quite qualified to say what any particular passage may mean, and Joyce’s critics ask in something like his own words, “Are we speachin d’anglas landadge, or are you spraking sea Djoytsch?” / That I think is not really Mr. Joyce’s fault. He is really not a lover of mystification, and he had done his best to make his meaning clear [...;’ here mentions Exagmination.] ‘This associative language is the reader’s first great stumbling block [...] It anticipates in the first place the break-up of the English language into dialects, a phenomenon that is already taking place slowly under our eyes in American, Scots and Irish literature - one has only to think of negro poetry in America or McDiarmid’s experiments in synthetic Scots. It also anticipates the universalisation of language.’ [516] ‘By this new work, Joyce has kept for himself a place in the mind of Europe. It would have been so easy for him, after Ulysses, to have been content with the position of an imitator of himself. [... &c.; 519]’ (‘Joyce: The Third Period’, in Irish Statesman, 12 April 1930, pp.114-16; rep. in Robert Deming, ed., James Joyce: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul 1970 [Vol. 2], p.515-18.)

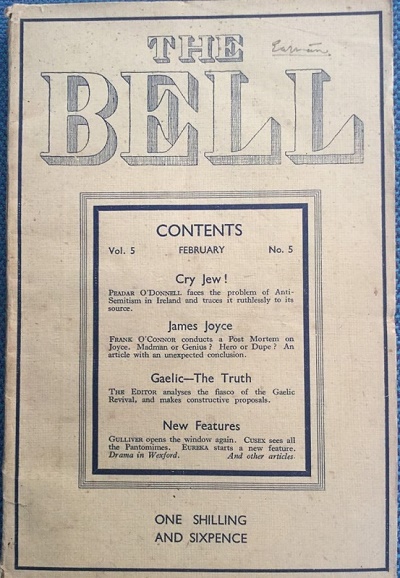

| The following references which Frank O’Connor made to Joyce in The Bell [1941] and The Backward Look (1967) have been compiled on Facebook by John McCourt (17.09.2020): | ||||

|

|

|||

Harold Nicholson (BBC, Autumn 1931): ‘[Joyce] seized the muse of Irish romance by her pallid neck, dragged her away from the mists and wailings of forgotten legend and set her in the sordid streets of Dublin of 1904. In so doing he did well. [...] You must abandon your receptivity, you must not expect a less or a story, you must expect only to absorb a new atmosphere, almost a new climate [...; Joyce has] added enormously to our capacity for observation: once you have absorbed the Joyce climate, you begin to notice things in your mind which have never occurred to you before. And to have given a new generation a whole new area of self-knowlede is surely an achievement of great importance.’ (BBC Broadcast, Autumn 1931; quoted in Patricia Hutchins, James Joyce’s World, Methuen 1957, p.176.) Hutchins further tells that Nicholson was forced to broadcast without mentioning the banned book Ulysses by name in a compromise reached with Sir John Reith, the Dir.-General, and that he (Nicholson) later wrote to her, ‘I was indignant at the time but I now [175] think that Reith was quite right is saying one cannot mention on the wireless a book [...] prohibited by the Home Office.’ (Ibid., pp.175-76). Note, the text was printed as ‘The Significance of James Joyce’ and ‘The Modernist Point of View’ in The Listener, 16 Dec. & 23 Dec. 1931; and rep. in Robert Deming, ed., James Joyce: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul 1970 [Vol. 2], p.560-63; only the first sentence in the version cited by Hutchins is given in Deming.

| [ previous ] | [ top ] | [ next ] |