James Joyce: Quotations (2) - Extracts from the Works [II]

| Index | File 1 | File 2 | File 3 | File 4 | File 5 |

| See the Works of James Joyce - Ricorso > Library > Index > Joyce - in this frame or new window |

| Extracts - Works [I] | Extracts - Works [II] | Comments on Works | Comments on Sundry | Extracts from Letters |

Extracts from Works [II]

“Ibsen’s New Drama” (Fortnightly Review, 1 April 1900) - I:

| [...] | |

To begin an account of a play of Ibsen’s is surely no easy matter. The subject is, in one way, so confined, and, in another way, so vast. It is safe to predict that nine-tenths of the notices of this play will open in some such way as the following: “Arnold Rubek and his wife, Maja [sic], have been married for four years, at the beginning of the play. Their union is, however, unhappy. Each is discontented with the other.’ So far as this goes, it is unimpeachable; but then it does not go very far. It does not convey even the most shadowy notion of the relations between Professor Rubek and his wife. It is a bald, clerkly version of countless, indefinable complexities. It is as though the history of a tragic life were to be written down rudely in two columns, one for the pros and the other for the cons. It is only saying what is literally true, to say that, in the three acts of the drama, there has been stated all that is essential to the drama. There is from first to last hardly a superfluous word or phrase. Therefore, the play itself expresses its own ideas as briefly and as concisely as they can be expressed in the dramatic form. It is manifest, then, that a notice cannot give an adequate notion of the drama. |

|

| [Quotes extensively from Act I.] | |

| It is evident, even from this mutilated account, that the first act is a masterly one. With no perceptible effort the drama rises, with a methodic natural ease it develops. The trim garden of the nineteenth-century hotel is slowly made the scene of a gradually growing dramatic struggle. Interest has been roused in each of the characters, sufficient to carry the mind into the succeeding act. The situation is not stupidly explained, but the action has set in, and at the close the play has reached a definite stage of progression. | |

Irene, too, is worthy of her place in the gallery of her compeers. Ibsen’s knowledge of humanity is nowhere more obvious than in his portrayal of women. He amazes one by his painful introspection; he seems to know them better than they know themselves. Indeed, if one may say so of an eminently virile man, there is a curious admixture of the woman in his nature. His marvellous accuracy, his faint traces of femininity, his delicacy of swift touch, are perhaps attributable to this admixture. But that he knows women is an incontrovertible fact. He appears to have sounded them to almost unfathomable depths. Beside his portraits the psychological studies of Hardy and Turgenieff, or the exhaustive elaborations of Meredith, seem no more than sciolism. With a deft stroke, in a phrase, in a word, he does what costs them chapters, and does it better. Irene, then, has to face great comparison; but it must be acknowledged that she comes forth of it bravely. Although Ibsen’s women are uniformly true, they, of course, present themselves in various lights. | |

Rubek himself is the chief figure in this drama, and, strangely enough, the most conventional. Certainly, when contrasted with his Napoleonic predecessor, John Gabriel Borkman, he is a mere shadow. It must be borne in mind, however, that Borkman is alive, actively, energetically, restlessly alive, all through the play to the end, when he dies; whereas Arnold Rubek is dead, almost hopelessly dead, until the end, when he comes to life. Notwithstanding this, he is supremely interesting, not because of himself, but because of his dramatic significance. Ibsen’s drama, as I have said, is wholly independent of his characters. They may be bores, but the drama in which they live and move is invariably powerful [...] | |

Again, there has not been lacking in the last few social dramas a fine pity for men — a note nowhere audible in the uncompromising rigour of the early eighties. Thus in the conversion of Rubek’s views as to the girl-figure in his masterpiece, “The Resurrection Day’, there is involved an all-embracing philosophy, a deep sympathy with the cross-purposes and contradictions of life, as they may be reconcilable with a hopeful awakening - when the manifold travail of our poor humanity may have a glorious issue. | |

‘Henrik Ibsen is one of the world’s great [66] men before whom criticism can make but feeble show. Appreciation, hearkening is the only true criticism. Further, that species of criticism which calls itself dramatic criticism is a needless adjunct to his plays. When the art of a dramatist is perfect the critic is superfluous. Life is not to be criticised, but to be faced and lived. Again, if any plays demand a stage they are the plays of Ibsen. Not merely is this so because his plays have so much in common with the plays of other men that they were not written to cumber the shelves of a library, but because they are so packed with thought. At some chance expression the mind is tortured with some question, and in a flash long reaches of life are opened up in vista, yet the vision is momentary unless we stay to ponder on it. It is just to prevent excessive pondering that Ibsen requires to be acted. Finally, it is foolish to expect that a problem, which has occupied Ibsen for nearly three years, will unroll smoothly before our eyes on a first or second reading. So it is better to leave the drama to plead for itself. But this at least is clear, that in this play Ibsen has given us nearly the very best of himself. The action is neither hindered by many complexities, as in The Pillars of Society, nor harrowing in its simplicity, as in Ghosts. We have whimsicality, bordering on extravagance, in the wild Ulfheim, and subtle humour in the sly contempt which Rubek and Maja entertain for each other. But Ibsen has striven to let the drama have perfectly free action. So he has not bestowed his wonted pains on the minor characters. In many of his plays these minor characters are matchless creations. Witness Jacob Engstrand, Tönnesen, and the demonic Molvik! But in this play the minor characters are not allowed to divert our attention. | |

| On the whole, When We Dead Awaken may rank with the greatest of the author’s work — if, indeed, it be not the greatest. It is described as the last of the series, which began with A Doll’s House - a grand epilogue to its ten predecessors. Than these dramas, excellent alike in dramaturgic skill, characterization, and supreme interest, the long roll of drama, ancient or modern, has few things better to show. [67; end.] | |

|

[ top ]

“Ibsen’s New Drama” (1900) - II: ‘Ibsen’s plays do not depend for their interest on the action, or on the incidents. Even the characters, faultlessly drawn though they be, are not the first thing in his plays. But the naked drama - either the perception of a great truth, or the opening up of a great question, or a great conflict which is almost independent of the conflicting actors, and has been and is of far-reaching importance - this is what primarily rivets our attention. Ibsen has chosen the average lives in their uncompromising truth for the groundwork of all his later plays.’ (Critical Writings, ed. Mason & Ellmann [1959] 1966, pp.47-67; p.63; quoted Klaus Reichart, ‘The European Background to Joyce’s Writing’, in The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce, ed. Derek Attridge, 1990, p.65.)

See also Joyce’s letter to Ibsen - as infra.

[ top ]

“An Irish Poet” - Review of William Rooney, Poems and Ballads; in Daily Express (11 Dec. 1902): ‘They are illustrative of the national temper, and because they are so the writers of the introductions do not hesitate to claim for them the highest honours. But this claim cannot be allowed, unless it is supported by certain evidences of literary sincerity. For a man who writes a book cannot be excused by his good intentions, or by his moral character; he enters into a region where there is a question of the written word, and it is well that this should be borne in mind, now that the region of literatures is assailed so fiercely by the enthusiast and the doctrine.’ (Rep. in Critical Writings, ed. Mason & Ellmann, [1959] 1966, p.85-87, p.85.) [Cont.]

Further [“An Irish Poet” (1902) - cont.]: ‘[...] But one must not look for these things [viz., the best of Mangan] when patriotism has laid hold of the writer. He has no care then to create anything accord to the art of literature, not the greatest of the arts, inded, but at least an art with a definite tradition behind it, possessing definite forms. [...T]hey have no spiritual or living energy, because they come from one in whom the spirit is in a manner dead, or at least in its own hell, a weary and foolish spirit, speaking of redemption and revenge, blaspheming against tyrants, and going forth, full of tears and curses, upon its infernal labours. Religion and all that is allied thereto can manifestly persuade men to great evil, and by writing these verses, even though they should, as the writers of the prefaces think, enkindle young men in Ireland to hope and activity, Mr. Rooney has been persuaded to great evil. / And yet he might have written well if he had not suffered from one of those big words which make us so unhappy.’ (Ibid., p.87.)

Note: Arthur Griffith reprinted much of the review without comment in United Irishman, 20 Dec. 1902, adding only the word ‘Patriotism’ in brackets after Joyce’s phrase ‘one of those big words’ (Ibid., p.84). Note also a possible source for that bon mot in Oscar Wilde’s An Ideal Husband where Mrs Cheveley berates Lord Goring: ‘Oh, don’t use big words. They mean so little. It is a transaction that is all. There is no good mixing up sentimentality in it. [...]’ (The Works of Oscar Wilde, London: Galley Press 1987, p.519.)

“Cataline” (1903; review of Henrik Ibsen’s first play of that title): ‘Moreover, as the breaking-up of tradition, which is the work of the modern era, discountenances the absolute and as no writer can escape the spirit of his time, the writer of dramas must remember now more than ever a principle of all patient and perfect art which bids him express his fable in terms of his characters.’ (Speaker, London, 21 March 1903, p.615; rep. in Critical Writings, ed. Mason & Ellmann [1959] 1966, pp.98-101; p.100.)

“The Soul of Ireland” - review of Lady Gregory’s Poets and Dreamers (Daily Express, 26 March 1903): ‘[...] Lady Gregory has truly set forth the old age of her country. In her new book she has left legends and heroic youth far behind, and has explored in a land almost fabulous in its sorrow and senility [...; 104]’

| Further: ‘In fine, her book, wherever it treats of the “folk”, sets forth in the fullness of its senility a class of mind which Mr Yeats has set forth with such delicate scepticism in his happiest book, The Celtic Twilight.’ [104; ...] |

| ‘This book, like so many other books of our time, is in part picturesque and in part an indirect or direct utterance of the central belief of Ireland. Out of the material and spiritual battle which has gone so hardily with her Ireland has emerged with many beliefs and memories, and with one belief - a belief in the incurable ignobility of the forces that have overcome her - and Lady Gregory, whose old men and women seem to be almost their own judges when they tell their wandering stories, might add to the passage from Whitman which forms her dedication, Whitman’s ambiguous word for the vanquished - “Battles are lost in the spirit in which they are won”.’ [105; End.] |

|

[ top ]

“Aristotle on Education” (1903): ‘The modern notion of Aristotle as a biologist - a notion popular among the advocates of “science” - is probably less true than the ancient notion of him as a metaphysician; and it is certainly in the higher applications of his severe method that he achieves himself.’ ([untitled review], in Daily Express, 3 Sept. 1903; reprint in Critical Writings, ed. Mason & Ellmann, 1966, p.109.) [See “Paris Notebook”, infra.]

Arnold Graves: James Joyce, review of “Mr Arnold Graves’s New Work” - review of Clytæmnestra, a Tragedy (Dublin Daily Express, 1 Oct. 1903): ‘Mr. Graves has chosen to call his play after the faithless wife of Agamemnon, and to make her nominally the cardinal point of interest. Yet from the tenor of the speeches, and inasmuch as the play is almost entirely a drama of the retribution which follows crime, Orestes being the agent of Divine vengeance, it is plain that the criminal nature of the queen has not engaged Mr. Graves’s sympathies. [126] / The play, in fact, is solved according to an ethical idea, and not according to that indifferent sympathy with certain pathological states which is so often anathematized by theologians of the street. Rules of conduct can be found in the books of moral philosophers, but “experts” alone can find them in Elizabethan comedy. Moreover, the interest is wrongly directed when Clytemnestra, who is about to imperil everything for the sake of her paramour, is represented as treating him with hardly disguised contempt, and again where Agamemnon, who is about to be murdered in his own palace by his own queen on his night of triumph, is made to behave towards his daughter Electra with a stupid harshness which is suggestive of nothing so much as of gout. Indeed, the feeblest of the five acts is the act which deals with the murder. Nor is the effect even sustained, for its second representation during Orestes’ hypnotic trance’ cannot but mar the effect of the real murder in the third act in the mind of an audience which has just caught Clytemnestra and Egisthus red-handed. / These faults can hardly be called venial, [...]’ (For full-text copy, see under Arnold Graves, as q.v. - or as attached.)

[ top ]

“The Bruno Philosophy” (1903) [review of J. Lewis McIntyre, Giordano Bruno, in Daily Express, 30 October 1903], rep. in Critical Writings, ed. Mason & Ellmann, 1964, 1966, pp.132-34: ‘[...] Certain parts of his philosophy - for it is many-sided - may be put aside. His treatises on memory, commentaries on the art of Raymond Lully, his excursions into that treacherous region from which even ironical Aristotle did not come undiscredited, the science of morality, have an interest only because they are so fantastical and middle-aged. / As an independent observer, Bruno, however, deserves high honour. More than Bacon or Descartes must he be considered the father of what is called modern philosophy. His system by turns rationalist and mystic, theistic and pantheistic is everywhere impressed with his noble mind and critical intellect, and is full of that ardent sympathy with nature as it is - natura naturata which is the breath of the Renaissance. In his attempt to reconcile the matter and form of the Scholastics - formidable names, which in his system as spirit and body retain little of their metaphysical character - Bruno has hardily put forward an hypothesis, which is a curious anticipation of Spinoza. Is it not strange, [133] then, that Coleridge should have set him down a dualist, a later Heraclitus, and should have represented him as saying in effect: “Every power in nature or in spirit must evolve an oppositie as the sole condition and means of its manifestation; and every opposition is, therefore, a tendency to reunion”? [See Coleridge’s The Friend, Essay XIII, ftn.] / And yet it must be the chief claim of any system like Bruno’s that it endeavours to simplify the complex. That idea of an ultimate principle, spiritual, indifferent, universal, related to any soul or to any material thing, as the Materia Prima of Aquinas is related to any material thing, unwarranted as it may seem in the view of critical philosophy, has yet a distinct value for the historian of religious ecstasies.’ (p.133-34.) Note: the last sentence given above is quoted in Sheldon Brivic, Joyce the Creator, 1985, p.46.) Joyce speaks of Bruno as ‘casting away tradition with the courage of early humanism’ [CW133], and goes on to call him ‘the vindicator of the freedom of intuition’ [CW134]. [See full text in RICORSO Library > Major Authors > James Joyce infra; also under Bruno in Notes, attached.]

“The Bruno Philosophy” (1903) II: ‘It is not Spinoza, it is Bruno, that is the god-intoxicated man. Inwards from the material universe, which, however, did not seem to him, as to the Neoplatonists the kingdom of the soul’s malady, or as to the Christians a place of probation, but rather his opportunity for spiritual activity, he passes, and from heroic enthusiasm to enthusiasm to unite himself with God. His mysticism is little allied to that of Molinos or to that of St John of the Cross; there is nothing in it of quietism or of the dark cloister: it is strong, suddenly rapturous, and militant. The death of the body is for him the cessation of a mode of being, and in virtue of this belief and of that robust character “prevaricating yet firm”, which is an evidence of that belief, he becomes of the number of those who loftily do not fear to die. For us his vindication of the freedom of intuition must seem an enduring monument, and among those who waged so honourable a war, his legend must seem the most honourable, more sanctified, and more ingenuous than that of Averroes or of Scotus Erigena.’ (Critical Writings, 1966, p.134.)

See also remarks in letter to Harriet Shaw Weaver: ‘[...] Bruno Nolano (of Nola) another great southern Italian was quoted in my first pamphlet The Day of the Rabblement. His philosophy is a kind [305] of dualism - every power in nature must evolve an opposite in order to realise itself and opposition brings reunion etc. etc. Tristan on his first visit to Ireland turned his name inside out. [... &c.]’ (27 Jan. 1925; Selected Letters, 1975, p.305; see also th source of this quotation as in under Coleridge, as attached.)

“Shakespeare Explained” - review of Shakespeare Studied in Eight Plays by Hon. A. S. Canning (London: Fisher, Unwin), in Daily Express [Dublin] (12 Nov. 1903). ‘In a short prefatory note the writer of this book states that he has not written it for Shakespearian scholars, who are well provided with volumes of research and criticism, but has sought to render the eight plays more interesting and intelligible to the general reader. It is not easy to discover in the book any matter for praise. The book itself is very long-nearly 500 pages of small type - and expensive. The eight divisions of it are long drawn out accounts of some of the plays of Shakespeare - plays chosen, it would seem, at haphazard. There is nowhere an attempt at criticism, and the interpretations are meagre, obvious, and commonplace. The passages “quoted” fill up perhaps a third of the book, and it must be confessed that the writer’s method of treating Shakespeare is (or seems to be) remarkably irreverent. Thus he “quotes” the speech made by Marcellus [sic] in the first act of Julius Caesar, and he has contrived to condense the first 16 lines of the original with great success, omitting six of them without any sign of omission. Perhaps it is a jealous care for the literary digestion of the general public that impels Mr Canning to give them no more than ten-sixteenths of the great bard. Perhaps it is the same care which dictates sentences such as the following:- “His noble comrade fully rivals Achilles in wisdom as in valour. Both are supposed to utter their philosophic speeches during the siege of Troy, which they are conducting with the most energetic ardour. They evidently turn aside from their grand object for a brief space to utter words of profound wisdom ...” [Ftn. Canning, p.6.] It will be seen that the substance of this book is after the manner of ancient playbills. Here is no psychological complexity, no cross-purpose, no interweaving of motives such as might perplex the base multitude. Such a one is a “noble character”, such a one a “villain”; such a passage is “grand”, “eloquent”, or “poetic”. One page in the account Richard the Third is made up of single lines or couplets and such non-committal remarks as “York says then”, “Gloucester, apparently surprised, answers”, “and York replies”, “and Gloucester replies”, “and York retorts”. There is something very naif about this book, but (alas!) the general public will hardly pay sixteen shillings for such naivete. And the same Philistine public will hardly read five hundred pages of “replies”, and “retorts” illustrated with misquotations. And even the pages are wrongly numbered. (Rep. in Occasional Critical and Political Writings [... &c.], ed Kevin Barry, Oxford UP 2000, pp.97-98.)

[ top ]

| ‘[It is] naïve to heap insults on the Englishman for his misdeeds in Ireland. A conqueror cannot be amateurish, and what England did in Ireland over the centuries is no different today in the Congo Free State ... [England] inflamed the factions and took possession of the wealth.’ (Occasional, Cultural and Political Writing (Oxford: OUP 2000, p.119. |

|

“Fenianism” (Piccolo del Sera, 1907): ‘Anyone who studies the history of the Irish revolution during the ninteenth century finds himself faced with a double struggle - the struggle of the Irish nation against the English government, and the struggle, perhaps no less bitter, between the moderate patriots and the so-called party of physical force. [... Fenians, Whiteboys, et al., have] always refused to be connected with either the English political parties or the Nationalist parliamentarians. They maintain (and in this assertion history fully supports them) that any concessions that have been granted to Ireland, England has granted unwillingly, and, as it is usually put, at the point of a bayonet. The intransigent press never ceases to greet the deeds of the Nationalist representatives at Westminster with virulent and ironic comments, and although it recognises that in view of England’s power armed revolt has [188] now become an impossible dream, it has never stopped inculcating in the minds of the coming generation the dogma of separatism." [Cont.]

“Fenianism” (Piccolo del Sera, 1907) - cont.: ‘Unlike Robert Emmet’s foolish uprising or the impassioned movement of Young Ireland in ‘45, the Fenianism of ‘67 was not one of the usual flashes of Celtic temperament that lighted the shadows for a moment and leave behind a darknes blacker than before.’ (Critical Writings, 1966, p.188-89; see discussion of this the ‘double struggle’, in Luke Gibbons, ‘Allegory, History and Irish Nationalism’, Transformations in Irish Culture, Cork UP 1996, p.146.) [Cont.]

“Fenianism” (Piccolo del Sera, 1907) - cont.: ‘Now, it is impossible for a desperate and bloody doctrine like Fenianism to continue its existence in an atmosphere like this, and in fact, as agrarian crimes and crimes of violence have become more and more rare, Fenianism too has once more changed its name and appearance. It is still a separatist doctrine but it no longer uses dynamite. The new Fenians are joined in a party which is called Sinn Féin (We Ourselves). They aim to make Ireland a bi-lingual Republic, and to this end they have established a direct steamship service between Ireland and France.’ (Op. cit., 1966, p.191.)

Cf. letter to Stanislaus: ‘If the Irish programme did not insist upon the Irish language I suppose I could call myself a nationalist.’ (Letters, Vol. II, p.187.)

[ top ]

“Home Rule Comes of Age” (Il Piccolo della Sera, 1907): ‘Probably the Lords will kill the measure, since that is their trade, but if they are wise, they will hesitate to alienate the sympathy of the Irish for constitutional agitation; especially now that India and Egypt are in an uproar and the overseas colonies are asking for an imperial federation. From their point of view, it would not be advisable to provoke by an obstinate veto the reaction of a people who, poor in everything else and rich only in political ideas, have perfected the strategy of obstructionism and made the word “boycott” an international war-cry.’ (Critical Writings, 1966, p.194; see full-text copy in RICORSO Library, “Authors > Joyce > Criticism” - via index or as attached.)

[ top ]

“Ireland, Island of Saints and Sages” (trans. from ”Irelanda, Isola dei Santi e dei Savi” [Slocum Coll., Yale UL], being a lecture of 27 April 1907 given at Università Popolare, Trieste) - extracts [I]: ‘[A]nyone who reads the history of the three centuries that precede the coming of the English must have a strong stomach, because the internecine strife, and the conflicts wit the Danes and the Norwegians, the black foreigners and the white foreigners, as they were called, follow each other so continuously and ferociously that they make this entire era a veritable slaughterhouse. The danes occupied all the principal ports on the east coast of the island and established a kingdom at Dublin, now the capital of Ireland, which has been a great city for about twenty centuries. Then the native kings killed each other off, taking well-earned rests from time to time in games of chess. Finally, the bloody victory of the usurper Brian Boru over the nordic hordes on the [159] sand dunes outside the walls of Dublin put an end to the Scandanavian raids. The Scandanavians, however, did not leave the country, but were gradually assimilated into the community, a fact that we must keep in mind if we want to understand the curious character of the modern Irishman.’ (Critical Writings, 1966, pp.159-60.)

“Ireland, Island of Saints and Sages” (1907) - extracts [II]: ‘It will seem strange that an island as remote as Ireland from the centre of culture could excel as a school for apostles, but even a superficial consideration will show us that the Irish nation’s insistence on developing its own culture by itself is not so much the demand of a young nation that wants to make good in the European concert as the demand of a very old nation to renew under new forms the glories of a past civilization.’ [...]

Further (“Ireland .. Saints and Sages”: ‘Our civilisation is a vast fabric, in which the most diverse elements are mingled, in which nordic aggressiveness and Roman law, the new bourgeois conventions and the remnant of a Syriac religion are reconciled. In such a fabric, it is useless to look for a thread that may have remained pure and virgin and without having undergone the influence of a neighbouring thread. What race, or what language (if we except [165] the few whom a playful will seems to have preserved in ice, like the people of Iceland) can boast of being pure today? And no race has less right to utter such a boast than the race now living in Ireland. Nationality (if it is not a convenient fiction like so many others to which the scalpels of present-day scientists have given the coup de grâce) must find its reason for being rooted in something that surpasses and transcends and informs changing things like blood and the human word. The mystic theologian who assumed the pseudonym of Dionysius, the pseudo-Areopagite, says somewhere, “God has disposed the limits of nations according to his angels”, and this probably is not a purely mystical concept. Do we not see that in Ireland the Danes, the Firbolgs, the Milesians from Spain, the Norman invaders, and the Anglo-Saxon settlers have united to form a new entity, one might say under the influence of a local deity? And, although the present race in Ireland is backward and inferior, it is worth taking into account the fact that it is the only race of the entire Celtic family that has not been willing to sell its birthright for a mess of pottage.’ (Critical Writings, 1966, p.165-66.)

“Ireland, Island of Saints and Sages” (1907) - extracts [III]: ‘I do not see the purpose of the bitter invectives against the English despoiler, the disdain for the vast Anglo-Saxon civilization, even though it is almost entirely a materialistic civilization, nor the empty boasts that the art of miniature in the ancient Irish books, such as the Book of Kells, the Yellow Book of Lecan, the Book of the Dun Cow, which date back to a time when England was an uncivilised country, is almost as old as the Chinese, and that Ireland made and exported to Europe its own fabrics for several generations before the first Fleming arrived in London to teach the English how to make bread. If an appeal to the past in this manner were valid, the fellahin of Cairo would have all the right in the world to disdain to act as porters for English tourists. Ancient Ireland is dead just as ancient Egypt is dead. Its death chant has been sung, and on its gravestone has been placed the seal. The old national soul that spoke during the centuries through the mouths of fabulous seers, wandering minstrels, and Jacobite [173] poets disappeared from the world with the death of James Clarence Mangan. With him the long tradition of the triple order of the old Celtic bards ended; and today other bards, animated by other ideas, have the cry.

One thing alone seems clear to me. It is well past time for Ireland to have done once and for all with failure. If she is truly capable of reviving, let her awake, or let her cover up her head and lie down decently in her grave forever. [... T]hough the Irish are eloquent, a revolution is not made of human breath and compromises. Ireland has already had enough of equivocations and misunderstandings. If she want to put on the play that we have waited for so long, this time let it be whole, and complete, and definitive. But our advice to the Irish producers is the same that our fathers gave them not so long ago - hurry up! I am sure that I, at least, will never see the curtain go up, because I will have already gone home on the last train.’ (Ibid. [end]; in Critical Writings, p.173-74.) [End; for longer extracts, see infra; for full version, go to RICORSO Library, “Irish Classics”, James Joyce - via index or direct)

[ top ]

“Ireland at the Bar” (Piccolo della Sera, 16 Sept. 1907) [... T]he Irish question is not solved even today, after six centuries of armed occupation and more than a hundred years of English legislation, which has reduced the population of the unhappy island from eight to four million, quadrupled the taxes, and twisted the agrarian problem into many more knots. In truth there is no problem more snarled than this one. The Irish themselves understand little about it, the English even less. For other people it is a black plague. / But on the other hand the Irish know that it is the cause of all their sufferings, and therefore they often adopt violent methods of solution. ( For remarks on Joyce’s treatment of the Maamtrasna murders, see Seamus Deane, Heroic Styles (1984) [extract] and Kevin Whelan, ‘The Memories of “The Dead”’, in The Yale Journal of Criticism [Johns Hopkins UP], 15:2 (2002) [extract] - both under Joyce > Commentary. )

Several years ago a sensational trial was held in Ireland. In a lonely place in a western province, called Maamtrasna, a murder was committed. Four or five townsmen, all belonging to the ancient tribe of the Joyces, were arrested. The oldest of them, the seventy year old Myles Joyce, was the prime suspect. Public opinion at the time thought him innocent and today considers him a martyr. Neither the old man nor the others accused knew English. [...] The figure of this dumbfounded old man, a remnant of a civilization not ours, deaf and dumb before his judge, is a symbol of the Irish nation at the bar of public opinion. Like him, she is unable to appeal to the modern conscience of England and other countries. The English journalists act as interpreters between Ireland and the English electorate, which gives them ear from time to time and ends up being vexed by the endless complaints of the Nationalist representatives who have entered her House, as she believes, to disrupt its order and extort money. Abroad there is no talk of Ireland except when uprisings break out, like those which made the telegraph office hop these last few days. Skimming over the dispatches from London (which, though they lack pungency, have something of the laconic quality of the interpreter mentioned above), the public conceives of the Irish as highwaymen with distorted faces, roaming the night with the object of taking the hide of every Unionist. And by the real sovereign of Ireland, the Pope, such news is received like so many dogs in church. Already weakened by their long journey, the cries are nearly spent when they arrive at the bronze door. The messengers of the people who never in the past have renounced the Holy See, the only Catholic people to whom faith also means the exercise of faith, are rejected in favour of messengers of a monarch, descended from apostates, who solemnly apostasized himself on the day of his coronation, declaring in the presence of his nobles and commons that the rites of the Roman Catholic Church are ‘superstition and idolatry’.

There are twenty million Irishmen scattered all over the world. The Emerald Isle contains only a small part of them. But, reflecting that, while England makes the Irish question the centre of all her internal politics she proceeds with a wealth of good judgment in quickly disposing of the more complex questions of colonial politics, the observer can do no less than ask himself why St. George’s Channel makes an abyss deeper than the ocean between Ireland and her proud dominator. / In fact, the Irish question is not solved even today, after six centuries of armed occupation and more than a hundred years of English legislation, which has reduced the population of the unhappy island from eight to four million, quadrupled the taxes, and twisted the agrarian problem into many more knots. In truth there is no problem more snarled than this one. The Irish themselves understand little about it, the English even less. For other people it is a black plague. / But on the other hand the Irish know that it is the cause of all their sufferings, and therefore they often adopt violent methods of solution. For example, twenty-eight years ago, seeing themselves reduced to misery by the brutalities of the large landholders, they refused to pay their land rents and obtained from Gladstone remedies and reforms. Today, seeing pastures full of well-fed cattle while an eighth of the population lacks means of subsistence, they drive the cattle from the farms. In irritation, the Liberal government arranges to refurbish the coercive tactics of the Conservatives, and for several weeks the London press dedicates innumerable articles to the agrarian crisis,which, it says, is very serious. It publishes alarming news of agrarian revolts, which is then reproduced by journalists abroad. [...] (In Critical Writings, ed. Ellmann & Mason, NY: Viking Press [1959] 1966, pp.197-200.)

See full-copy in RICORSO Library > Authors > James Joyce > Criticism - in this frame or new window.

In 1914 Joyce attempted to publish his articles from Il Piccolo della Sera (1907) in book form under the suggested title of Ireland at the Bar and sent them to a Genovese publisher with a cover letter stating: ‘This year the Irish problem has reached an acute phases, and indeed, according to the latest news, England, owing to the Home Rule question, is on the brink of civil war. The publication of a volume of Irish essays would be of interest to the Italian public. I am an Irishman (from Dublin), and though these articles have absolutely no literary value, I believe they set out the problem sincerely and objectively.’ (Quoted in Georgio Melchiori, ‘Joyce’s Feast of Languages: Seven Essays and Ten Notes’, in Joyce Studies in Italy, 4, ed. Franca Ruggieri, Rome: Bulzone Editore 1995, pp.113-14; quoted in Eric Bulson, Introduction to James Joyce, OUP 2006, p.25. Bulson also draws on John McCourt, The Years of Bloom, James Joyce in Trieste 1904-1920, Lilliput Press 2000, and his own article ‘Getting Noticed: Joyce’s Italian Translations’ in Joyce Studies Annual 2001, pp.10-37. [ See other accounts of the events at Maamtrasna and the subsequent trial in Timothy Harrington, The Maamtrasna Massacre: Impeachment [...; &c.] (Dublin 1884) [available online, or see extract under Harrington - supra], and that by Lord Chief Justice Peter O’Brien in his Reminiscences (1916) - as infra. ] [ top ]

“Oscar Wilde: The Poet of Salomé” (1909): ‘Here we touch on the pulse of Wilde’s art - sin. He deceived himself into thinking that he was the bearer of good news of neo-paganism to an enslaved people. His own distinctive qualities, the qualities, perhaps, of his race - keenness, generosity, and a sexless intellect - he placed at the service of a theory of beauty which, according to him, was to bring back the golden age and the joy of the world’s youth. But if some truth adheres to his subjective interpretations of Aristotle, to his restless thought that proceeds by sophisms rather than syllogisms, to his assimilations of natures as foreign to his as the delinquent is to the humble, at its very base is the truth inherent in the soul of Catholicism: that man cannot reach the divine heart except through that sense of separation and loss called sin.’ (Ellsworth Mason & Ellmann, eds., The Critical Writings, 1964, pp.204-05; Richard Ellmann, Oscar Wilde: A Collection of Essays, NY: Prentice Hall, 1969, p.60; quoted in part Seamus Deane, Heroic Styles: The Tradition of an Idea, Derry: Field Day 1984, p.10, and at more length in Deane, ‘Joyce the Irishman’, The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce, ed. Derek Attridge, Cambridge UP 1990, p.35.)

Note: Joyce’s phrase ‘that sense of separation and loss called sin’ closely echoes Owen Aherne’s in Yeats’s story “The Tables of the Law”: ‘“At first I was full of happiness,” he replied, “for I felt a divine ecstasy, an immortal fire in every passion, in every hope, in every desire, in every dream; and I saw, in the shadows under leaves, in the hollow waters, in the eyes of men and women, its image, as in a mirror; and it was as though I was about to touch the Heart of God. Then all changed and I was full of misery; and in my misery it was revealed to me that man can only come to that Heart through the sense of separation from it which we call sin, and I understood that I could not sin, because I had discovered [209] the law of my being, and could only express or fail to express my being, and I understood that God has made a simple and an arbitrary law that we may sin and repent!”’ [My itals.] (See G. J. Watson, ed., W. B. Yeats: Short Fiction, Penguin 1995, pp.209-10; cited also in Kevin Barry, ed., Occasional, Critical, and Political Writing [of] James Joyce, OUP 2000), p.325 .

Note: Mason & Ellmann [op. cit.], write: ‘Compare Aherne in Yeats’s Tables of the Law [sic], which Joyce knew by heart: ‘and in my misery .... which we call sin.’ (Critical Writings, 1964, p.205, n.1.)

[ top ]

“Daniel Defoe” [Daniele De Foe] - in “Verismo ed idealismo nella letterature inglese: Daniele De Foe & William Blake” - Joyce’s second lecture at Università Popolare; Trieste, March 1912: ‘[... The English mind finds its epitome in] the manly independence, the unconscious cruelty, the persistence, the slow but effective intelligence, the sexual apathy, the practical and well-balanced religiosity, the calculating silence [of Robinson Crusoe].’ [Cont.]

“Daniel Defoe” - cont.: ‘The true symbol of the British conquest is Robinson Crusoe, cast away on a desert island, in his pocket a knife and a pipe, becomes an architect, a knife-grinder, an astronomer, a baker, a shipwright, a potter, a saddler, a farmer, a tailor, an umbrella-maker, and a clergyman. He is the true prototype of the British colonist, as Friday (the trusty savage who arrives on an unlucky day) is the symbol of the subject races. The whole Anglo-Saxon spirit is in Crusoe.’ (Quoted in Dominic Maganiello, Joyce’s Politics, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul 1980, p.109; but cf. a variant translation in Richard Ellmann, James Joyce): ‘[Crusoe] shipwrecked on a lonely island with a knife and a pipe in his pocket became architect, carpenter, knife-sharpener, baker, astronomer, shipbuilder, potter, farmer, saddle-maker, tailor, umbrella-maker, and clergyman.’ (James Joyce: The Critical Writings [1957], Rev. Edn. 1966, p.330),

Richard Ellmann: ‘It was fitting that that Crusoe should have been evolved by Defoe, who, Joyce told his audience, was the first English writer to throw off the Italian influence under which English literature had until then laboured.’). Further, ‘Seated at the bedside of a boy visionary [i.e., “Duncan Campbell”], gazing at his raised eyelids listing to his breathing, examining the position of his head, noting his fresh complexion, Defoe is the realist in the presence of the unknown, it is the experience of the man who struggles and conquers in the presence of a dream which he fears may fool him; he is, finally, the Anglo-Saxon in the presence of the Celt.’ (Occas. Writings, ed. Barry, OUP 2001, p.171; all quoted in Eric Bulson, Cambridge Introduction to James Joyce, Cambridge UP 2006, p.29; and see Bulson’s remarks under Commentary, infra.)

Bibl. note: The lecture on Defoe was omitted from the Critical Writings (1959) in view of a prior arrangement with the James Joyce Estate, but included in Kevin Barry, ed., Occasional Critical and Political Writings (OUP 2000.)

[ top ]

“William Blake”, in “Verismo ed idealismo nella letterature inglese: Daniele De Foe & William Blake” - Joyce’s second lecture at Università Popolare; Trieste, March 1912 [ extant MSS, trans. into English in Critical Writings of James Joyce, ed. Ellsworth Mason & Richard Ellmann (1959; 1966 edn)]: ‘[...] The same idealism that possessed and sustained Blake when he hurled his lightning against human evil and misery prevented him from being cruel to the body even of a sinner, the frail curtain of flesh, as he calls it in the mystical book of Thel, that lies on the bed of our desire. The episodes that show the primitive goodness of his heart are numerous in the story of his life.’ (CW, p.216.)

Further: ‘Like many other men of great genius, Blake was not attracted to cultured and refined women. Either he preferred to drawing room graces and an easy and broad culture (if you will allow me to borrow a commonplace from theatrical jargon) the simple woman of hazy and sensual mentality, or, in his unlimited egoism, he wanted the soul of his beloved to be entirely of a slow and painful creation of his own, free and purifying daily under his eyes, the demon (as he says) hidden in the clouds. Whichever is true, the fact is that Mrs. Blake was neither very pretty nor very intelligent. She was, in fact, illiterate, and the poet took pains to teach her to read and write [...]’ (CW, 217; see also notes on ‘Egoism in Joyce’ - infra.) [Cont.]

“William Blake” (Trieste, March 1912) - cont.: “[...] Elemental beings and spirits of dead great men often came to the poet’s room at night to speak with him about art and the imagination. Then Blake would leap out of bed, and, seizing his pencil, remain long hours in the cold London night drawing the limbs and lineaments of the visions, while his wife, curled up beside his easy chair, held his hand lovingly and kept quiet so as not to disturb the visionary ecstasy of the seer. When the vision had gone, about daybreak his wife would get back into bed, and Blake, radiant with joy and benevolence, would quickly begin to light the fire and get breakfast for the both of them. We are amazed that the symbolic beings Los and Urizen and Vala and Tiriel and Enitharmon and the shades of Milton and Homer came from their ideal world to a poor London room, and no other incense greeted their coming than the smell of East Indian tea and eggs fried in lard. Isn’t this perhaps the first time in the history of the world that the Eternal spoke through the mouth of the humble?’ (CW, p.218.) [Cont.]

“William Blake” (Trieste, March 1912) - cont.: “[..] If we must accuse of madness every great genius who does not believe in the hurried materialism now in vogue with the happy fatuousness of a recent college graduate in the exact sciences, little remains for art and universal philosophy. Such a slaughter of the innocents would take in a large part of the peripatetic system, all of medieval metaphysics, a whole branch of the immense symmetrical edifice constructed by the Angelic Doctor, St. Thomas Aquinas, Berkeley’s idealism, and (what a combination) the scepticism that ends with Hume. With regard to art, then, those very useful figures, the photographer and court stenographer, would get by all the more easily. The presentat of such an art and such a philosophy, flowering in the more or less distant future in the union of two social forces felt more strongly in the market-place every day women and the proletariat - will reconcile, if nothing else, every artist and philosopher to the shortness of life on earth.’ (CW, p.220.) [Cont.]

“William Blake” (Trieste, March 1912) - cont.: “To determine what position Blake must be assigned in the hierarchy of occidental mystics goes beyond the scope of this lecture. It seems to me Blake is not a great mystic. [...] Blake is probably less inspired by Indian mysticism than Paracelsus, Jacob Behmen [Boehme], or Swedenborg; at any rate, he [220] is less objectionable. In him, the visionary faculty is directly connected with the artistic faculty. One must be, in the first place, well-disposed to mysticism, and in the second place, endowed with the patience of a saint in order to get an idea of what Paracelsus and Behmen mean by their cosmic exposition of the involution and evolution of mercury, salt, sulphur, body, soul and spirit. Blake naturally belongs to another category, that of the artists, and in this category he occupies, in my opinion, a unique position, because he unites keenness of intellect with mystical feeling. This first quality is almost completely lacking in mystical art. St. John of the Cross, for example, one of the few idealist artists worthy to stand with Blake, never reveals either an innate sense of form or a coordinating force of the intellect in his book The Dark Night of the Soul, that cries and faints with such an ecstatic passion. / The explanation lies in the fact that Blake had two spiritual masters, very different from each other, yet alike in their formal precision - Michelangelo Buonarotti and Emanuel Swedenborg. [...; &c.’] (p.221.) [Cont.]

“William Blake” (Trieste, March 1912) - cont.: ‘Armed with this two-edged sword, the art of Michaelangelo and the revelations of Swedenborg, Blake killed the dragon of experience and natural wisdom, and, by minimising space and time and denying the existence of memory and the senses, he tried to paint his works on the void of the divine bosom. [See note, infra.]To him, each moment shorter than a pulse-beat was equivalent in its duration to six thousand years, because in such an infinitely short instant the work of the poet is conceived and born. To him, all space larger than a red globule of human blood was visionary, created by the hammer of Los, while in a space smaller than a globule of blood we approach eternity, of which our vegetable world is but a shadow. Not with the eye, then, but beyond the eye, the soul and the supreme move must look, because the eye, which was born in the night while the soul was sleeping in rays of light, will also die in the night. [...] The mental process by which Blake arrives at the threshold of the infinite is a similar process. Flying from the infinitely small to the infinitely large, from a drop of blood to the universe of stars, his soul is consumed by the rapidity of flight, and finds itself renewed and winged and immortal on the edge of th dark ocean of God. And althought he based his art on such idealist premises, convinced that eternity was in love with the products of time, this sons of God with the sons of [MS ends here].’ (Critical Writings, 1959, 1966 Edn., pp.221-22; quoted [in part] in Richard Ellmann, James Joyce, 1965 Edn., p.330.)

“William Blake” (Trieste, March 1912) - cont.: ‘In English literature Blake represents the most significant and the truest form of idealism. He was not however an Anglo-Saxon. Instead he possessed all the qualities contrary to this type and most of all his hatred of commerce. He was Irish and he manifested in his art those characteristics most particular to his people.’ (Occas. Writings, ed. Barry, OUP 2001, q.p.; quoted in Eric Bulson, Cambridge Introduction to James Joyce, Cambridge UP 2006, p.29; not included in the version in Critical Writings, ed. Mason & Ellmann.)

[For full text, see RICORSO Library, “Major Authors”, via index, or direct.] Note - for “void” [supra], cf. Stephen in “Scylla & Charybdis”: ‘Fatherhood [...] is a mystical estate, an apostolic succession, from only begetter to only begotten. On that mystery and not on the madonna which the cunning Italian intellect flung to the mob of Europe the church is founded and founded irremovably because founded, like the world, macro- and microcosm, upon the void.’ (Ulysses, Penguin Edn. 1967, p.207; [my itals.].)

“The Shade of Parnell” (Il Piccolo della Sera, 16 May, 1912): ‘[...] The Fact that Ireland now wishes to make common cause with British democracy should neither surprise nor persuade anyone. For seven centuries she has never been a faithful subject of England. Neither, on the other hand, has she been faithful to herself. She has entered the British domain without forming an integral part of it. She has abandoned her own language almost entirely and accepted the language of the conqueror without being [212] able to assimilate the culture or adapt herself to the mentality of which this language is the vehicle. She has betrayed her heroes, always in the hour of need and always without gaining recompense. She has hounded her spiritual creators into exile only to boast about them. She has served only one master well, the Roman Catholic Church, which, however, is accustomed to pay it faithful in long term drafts.’ (Critical Writings, 1966, p.212.)

[ top ]

Exiles (1918) - I. RICHARD: ‘I never tried to do such a thing, Bertha. You know I cannot be severe with a child.’ BERTHA: ‘Because you never loved your own mother. A mother is always a mother, no matter what. I never heard of any human being that did not love the mother that brought him into the world, except you.’ RICHARD (to ROBERT HAND): ‘I told you that when I saw your eyes this afternoon I felt sad. Your humility and confusion, ifelt, united you to me in brotherhood. At that moment I felt our whole life together in the past, and I longed to put my arm around your neck.’ ROBERT: ‘lt is noble of you, Richard to forgive me like this.’ RICHARD: ‘I told you that I wished you not to do anything false and secret against me against our friendship, against her not to steal her away from me craftily, secretly, meanly ... in the dark, in the night ... you, Robert, my friend.’ ROBERT: ‘I know - And it was noble of you.’ RICHARD: ‘No. Not noble - Ignoble.’ ROBERT: ‘Why?’ RICHARD: ‘That is what I must tell you too. Because in the very core of my ignoble heart l longed to be betrayed by you and by her in the dark, in the night secretly, meanly, craftily - By you, my best, friend, and by her. I longed for that passionately, and ignobly, to be dishonoured forever in love and in lust to be ... (Quoted in Catherine J. Hemphill, UG Diss., UUC 2003.)

Exiles (1918) - II, BERTHA [in answer to Beatrice’s remark, ‘Don’t let them humble you, Mrs. Rowan’]: Humble me! I am very proud of myself, if you want to know. What have they ever done for him? I made him a man. What are they all in his life? No more than the dust under his boots. He can despise me too, like the rest of them - now. And you can despise me. But you will never humble me, any of you.’ (Quoted in Padraic Colum, review of Exiles, in Nation, 12 Oct. 1918; rep. in Robert Deming, James Joyce: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul 1970 [Vol. 1], p.114-45; p.145.) Colum writes of the Bertha that Richard is deeply in love with her and eloped with her some years before, but that ‘Bertha is not adequate to his whole personality [so that] he corresponds with Beatrice Justice. In quoting the above passage, he writes in conclusion: ‘It is in passages such as this that James Joyce shows his power to draw a real and distinctive character’ - yet, in so writing, Colum must have had some intuition that the Richard-Bertha relationship is modelled on that between Joyce and Nora Barnacle.

[ top ]

“I Hear an Army”: ‘I hear an army charging upon the land, And the thunder of horses plunging; foam about their knees: Arrogant, in black armour, behind them stand, / Disdaining the reins, with fluttering whips, the Charioteers. // They cry into the night their battle name: / I moan in sleep when I hear afar their whirling laughter. / They cleave the gloom of dreams, a blinding flame, / Clanging, clanging upon the heart as upon an anvil. // They come shaking in triumph their long grey hair: / They come out of the sea and run shouting by the shore. / My heart, have you no wisdom thus to despair? / My love, my love, my love, why have you left me alone?’ (Des Imagistes, 1914, rep. in Peter Jones, ed., Imagist Poetry, Penguin Classics 2001, p.344; also at Twentieth-century Poetry in English, the website of Prof. Eiichi Hishikawa [Kobe University] - online, with note: a version with different lineation appears as Chamber Music XXXVI.)

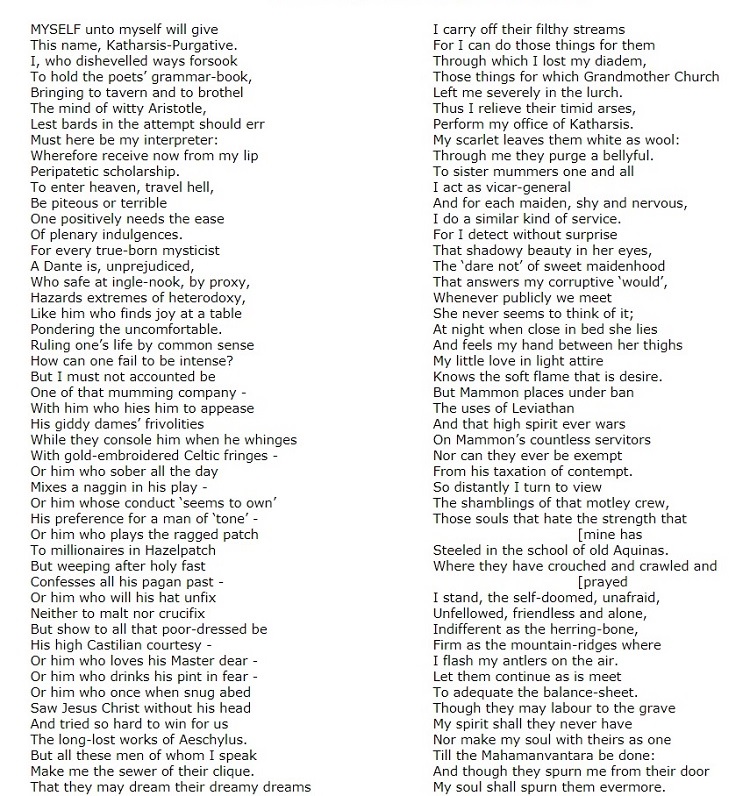

[ See photo-pages of original broadside - via index or as attached.

Textual version [copiable]: Myself unto myself will give / This name, Katharsis-Purgative. / I, who dishevelled ways forsook / To hold the poets’ grammar-book, / Bringing to tavern and to brothel / The mind of witty Aristotle, / Lest bards in the attempt should err / Must here be my interpreter: / Wherefore receive now from my lip / Peripatetic scholarship. / To enter heaven, travel hell, / Be piteous or terrible / One positively needs the ease / Of plenary indulgences. / For every true-born mysticist / A Dante is, unprejudiced, / Who safe at ingle-nook, by proxy, / Hazards extremes of heterodoxy, / Like him who finds joy at a table / Pondering the uncomfortable. / Ruling one’s life by common sense / How can one fail to be intense? / But I must not accounted be / One of that mumming company - / With him who hies him to appease / His giddy dames’ frivolities / While they console him when he whinges / With gold-embroidered Celtic fringes - / Or him who sober all the day / Mixes a naggin in his play - / Or him whose conduct ‘seems to own’ / His preference for a man of ‘tone’ - / Or him who plays the ragged patch / To millionaires in Hazelpatch / But weeping after holy fast / Confesses all his pagan past - / Or him who will his hat unfix / Neither to malt nor crucifix / But show to all that poor-dressed be / His high Castilian courtesy - / Or him who loves his Master dear - / Or him who drinks his pint in fear - / Or him who once when snug abed / Saw Jesus Christ without his head / And tried so hard to win for us / The long-lost works of Aeschylus. / But all these men of whom I speak / Make me the sewer of their clique. / That they may dream their dreamy dreams / I carry off their filthy streams / For I can do those things for them / Through which I lost my diadem, / Those things for which Grandmother Church / Left me severely in the lurch. / Thus I relieve their timid arses, / Perform my office of Katharsis. / My scarlet leaves them white as wool: / Through me they purge a bellyful. / To sister mummers one and all / I act as vicar-general / And for each maiden, shy and nervous, / I do a similar kind of service. / For I detect without surprise / That shadowy beauty in her eyes, / The ‘dare not’ of sweet maidenhood / That answers my corruptive ‘would’, / Whenever publicly we meet / She never seems to think of it; / At night when close in bed she lies / And feels my hand between her thighs / My little love in light attire / Knows the soft flame that is desire. / But Mammon places under ban / The uses of Leviathan / And that high spirit ever wars / On Mammon’s countless servitors / Nor can they ever be exempt / From his taxation of contempt. / So distantly I turn to view / The shamblings of that motley crew, / Those souls that hate the strength that mine has / Steeled in the school of old Aquinas. / Where they have crouched and crawled and prayed / I stand, the self-doomed, unafraid, / Unfellowed, friendless and alone, / Indifferent as the herring-bone, / Firm as the mountain-ridges where / I flash my antlers on the air. / Let them continue as is meet / To adequate the balance-sheet. / Though they may labour to the grave / My spirit shall they never have / Nor make my soul with theirs as one / Till the Mahamanvantara be done: / And though they spurn me from their door / My soul shall spurn them evermore. [ top ]

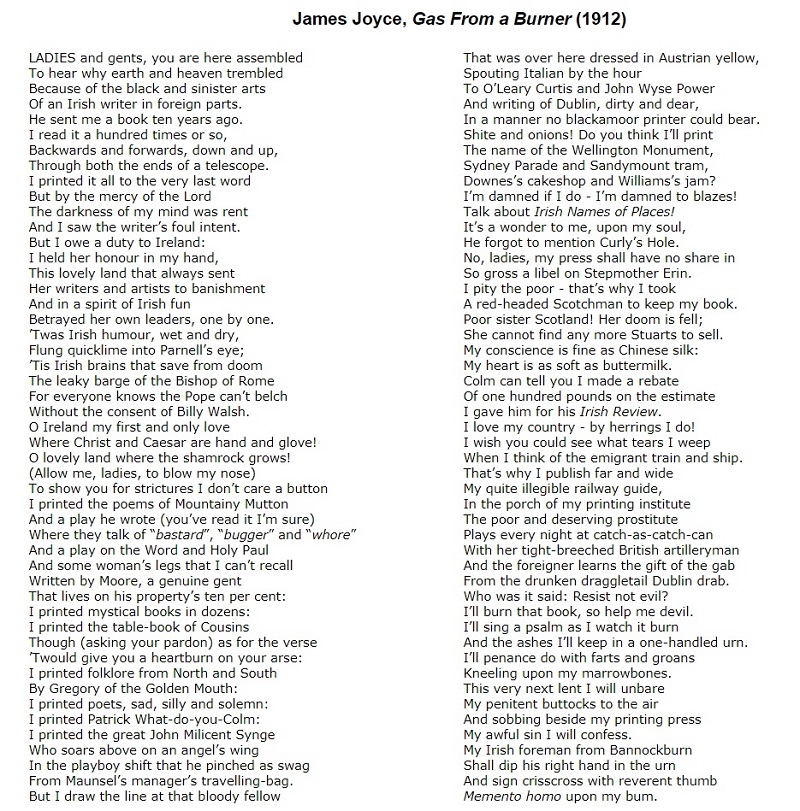

See images of some extant copies at RICORSO > lIBRARY > Authors > Irish Classics > Joyce > Poetry > Gas from a Burner - in this frame, or in a separate window.

Digital text (copiable): Ladies and gents, you are here assembled / To hear why earth and heaven trembled / Because of the black and sinister arts / Of an Irish writer in foreign parts. / He sent me a book ten years ago / I read it a hundred times or so, / Backwards and forwards, down and up, / Through both the ends of a telescope. / I printed it all to the very last word / But by the mercy of the Lord / The darkness of my mind was rent / And I saw the writer’s foul intent. / But I owe a duty to Ireland: / I held her honour in my hand, / This lovely land that always sent / Her writers and artists to banishment / And in a spirit of Irish fun / Betrayed her own leaders, one by one. / ‘Twas Irish humour, wet and dry, / Flung quicklime into Parnell’s eye; / ‘Tis Irish brains that save from doom / The leaky barge of the Bishop of Rome / For everyone knows the Pope can’t belch / Without the consent of Billy Walsh. / O Ireland my first and only love / Where Christ and Caesar are hand and glove! / O lovely land where the shamrock grows! / (Allow me, ladies, to blow my nose) / To show you for strictures I don’t care a button / I printed the poems of Mountainy Mutton / And a play he wrote (you’ve read it I’m sure) / Where they talk of “bastard”, “bugger” and “whore” / And a play on the Word and Holy Paul / And some woman’s legs that I can’t recall / Written by Moore, a genuine gent / That lives on his property’s ten per cent: / I printed mystical books in dozens: / I printed the table-book of Cousins / Though (asking your pardon) as for the verse / ‘Twould give you a heartburn on your arse: / I printed folklore from North and South / By Gregory of the Golden Mouth: / I printed poets, sad, silly and solemn: / I printed Patrick What-do-you-Colm: / I printed the great John Milicent Synge / Who soars above on an angel’s wing / In the playboy shift that he pinched as swag / From Maunsel’s manager’s travelling-bag. / But I draw the line at that bloody fellow / That was over here dressed in Austrian yellow, / Spouting Italian by the hour / To O’Leary Curtis and John Wyse Power / And writing of Dublin, dirty and dear, / In a manner no blackamoor printer could bear. / Shite and onions! Do you think I’ll print / The name of the Wellington Monument, / Sydney Parade and Sandymount tram, / Downes’s cakeshop and Williams’s jam? / I’m damned if I do”I’m damned to blazes! / Talk about Irish Names of Places! / It’s a wonder to me, upon my soul, / He forgot to mention Curly’s Hole. / No, ladies, my press shall have no share in / So gross a libel on Stepmother Erin. / I pity the poor--that’s why I took / A red-headed Scotchman to keep my book. / Poor sister Scotland! Her doom is fell; / She cannot find any more Stuarts to sell. / My conscience is fine as Chinese silk: / My heart is as soft as buttermilk. / Colm can tell you I made a rebate / Of one hundred pounds on the estimate / I gave him for his Irish Review. / I love my country—by herrings I do! / I wish you could see what tears I weep / When I think of the emigrant train and ship. / That’s why I publish far and wide / My quite illegible railway guide, / In the porch of my printing institute / The poor and deserving prostitute / Plays every night at catch-as-catch-can / With her tight-breeched British artilleryman / And the foreigner learns the gift of the gab / From the drunken draggletail Dublin drab. / Who was it said: Resist not evil? / I’ll burn that book, so help me devil. / I’ll sing a psalm as I watch it burn / And the ashes I’ll keep in a one-handled urn. / I’ll penance do with farts and groans / Kneeling upon my marrowbones. / This very next lent I will unbare / My penitent buttocks to the air / And sobbing beside my printing press / My awful sin I will confess. / My Irish foreman from Bannockburn / Shall dip his right hand in the urn / And sign crisscross with reverent thumb / Memento homo upon my bum.

[ top ]

“She Weeps over Rahoon”: ‘Rain on Rahoon falls softly, softly falling / Where my dark lover lies. / Sad is the voice that calls me, sadly calling, / At grey moonrise. // Love, hear thou / How soft, how sad his voice is ever calling, / Ever unanswered and the dark rain falling, / Then as now. // Dark too our hearts, O love, shall lie and cold / As his sad heart has lain / Under the moongrey nettles, the black mould / And muttering rain.’ (Trieste 1913; quoted in Ellmann, James Joyce, 1965 Edn., p.334.)

“A Flower Given to My Daughter”: ‘Frail the white rose and frail are / Her hands that gave / Whose soul is sere and paler / than time’s wan wave. // Roseril and fair - yet frailer / A wonder wild / In gentle eyes thou veilest, / My blueveined child.’ (Pomes Penyeach; quoted in Stan Gébler Davies, James Joyce: A Portrait of the Artist, Davis-Poynter 1975, p.266.)

“Pride of old Ireland”: ‘Of spinach and gammon / Bull full to the crupper / White lice and black famine / Are the Mayor of Cork’s supper; // But the pride of old Ireland / Must be damnably humbled / If a Joyce is found cleaning / The boots of a Rumbold.’ (Verses incl. in letter to Stanislaus, 1922; quoted in Richard Ellmann, James Joyce, 1965 Edn., p.547.)

“Ecce Puer” (1932): ‘Of the dark past / A child is born; / With joy and grief / My heart is torn. // Calm in his cradle / The living lies. / May love and mercy / Unclose his eyes! // Young life is breathed / On the glass; / The world that was not / Comes to pass. // A child is sleeping: / An old man gone. / O, father forsaken, / Forgive your son!’ [See formatted version in RICORSO Library > Joyce - via index or as attached.]

“A Prayer”: ‘Again! / Come, give, yield all your strength to me! / From far a low word breathes on the breaking brain / Its cruel calm, submission’s misery, / Gentling her awe as to a soul predestined. / Cease, silent love! My doom! // Blind me with your dark nearness, / O have mercy, beloved enemy of my will! / I dare not withstand the cold touch that I dread. / Draw from me still / My slow life! Bend deeper on me, threatening head, / Proud by my downfall, remembering, pitying / Him who is, him who was! // Again! / Together, folded by the night, they lay on earth. I hear / From far her low word breathe on my breaking brain. / Come! I yield. Bend deeper upon me! I am here. / Subduer, do not leave me! Only joy, only anguish, / Take me, save me, soothe me, O spare me!’ (Paris, 1924; Pomes Penyeach [1927], London: Faber 1966, p.14; Poems and Shorter Writings, 1991, p.63.)

[ top ]

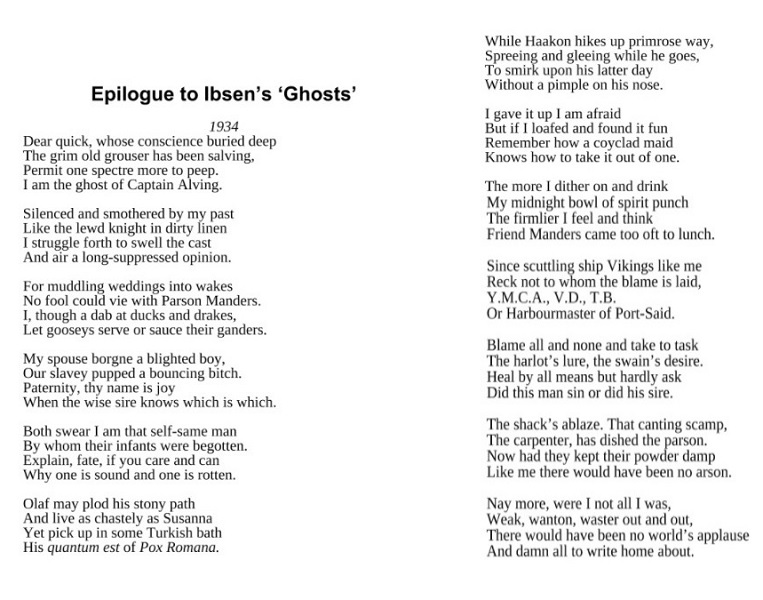

April 1934; first published in Herman Gorman, James Joyce (Rinehart 1939); rep. in Critical Writings (1959). [ top ]

Unpublished poem by Joyce in holograph copy held by J. F. Byrne (written on two library-slips - 1902)

I. III. Oh it is cold and still — alas!—

The soft white bosom of my love,

Wherein no mood of guile or fear,

But only gentleness did move.

She hears as standing on the shore,

A bell above the water’s toll,

She heard the call of, “come away”

Which is the calling of the soul.The fiddle has a mournful sound

That’s playing in the street be -

And who is there to say me no?

We lie upon the bed of love

And lie together in the ground:

To live, to love and to forget

Is all the wisdom lovers have.II. They covered her with linen white

And set white candles at her head

And loosened out her glorious hair

And laid her on a snow-white bed.

I saw her passing like a cloud,

Discreet and silent and apart.

O, little joy, and great sorrow

Is all the music of the heart.—For further details see J. F. Byrne The Silent Years (NY 1953) - extract as attached.

[ back ]

[ top ]

[ next ]